The latest offering at the National Gallery Singapore is the exhibition, Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s. It is an ambitious exhibition, and curators from three important institutions worked together across a period of more than four years in order to pull the project off. In this interview, we talk to Dr Adele Tan about Huang Yong Ping’s work, Reptiles. It was not included in the Japanese or Korean exhibitions, and makes its debut appearance in the Singapore iteration of Awakenings. This piece is the last part of a two-part series on curating the groundbreaking exhibition. Read the first part of this series here.

Dr Adele Tan studied English Literature at the National University of Singapore and received her MA and PhD in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is Senior Curator at National Gallery Singapore, overseeing the post-1970s collection and displays, as well as contemporary commissions for the museum. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary art in Southeast Asia and China, with a special interest in performative practices and new media. She was assistant editor at the British journal Third Text and is a member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) Singapore.

Dr Adele Tan studied English Literature at the National University of Singapore and received her MA and PhD in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She is Senior Curator at National Gallery Singapore, overseeing the post-1970s collection and displays, as well as contemporary commissions for the museum. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary art in Southeast Asia and China, with a special interest in performative practices and new media. She was assistant editor at the British journal Third Text and is a member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) Singapore.

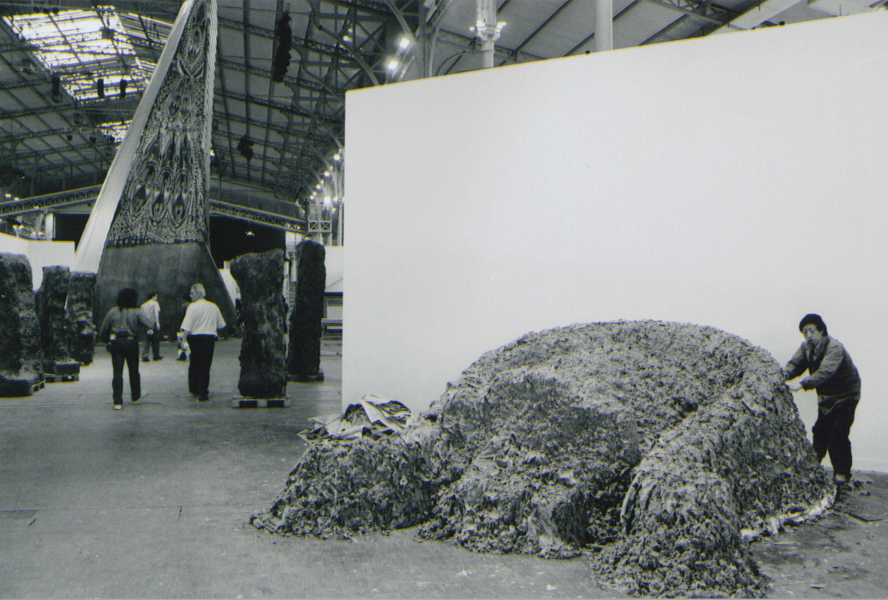

¹ Reptiles, Huang Yong Ping

1989, Current version made in 2013, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Photography: National Gallery Singapore

1989, Current version made in 2013, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Photography: National Gallery Singapore

THE FABLED ARTWORK’S PAST AND PRESENT LIVES

Dr Adele Tan (AT): Reptiles is a work of great pedigree. It was shown in the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, and this was a significant exhibition because it came at a time where global art as an idea didn’t yet exist. This was one of the earliest attempts to bring together a fairly sizeable group of artists, and half of these artists were not based in Euro-America. It attempted to bring non-European or non-American artists into the fold, and to create dialogue between these different practices. In that sense, Magiciens de la Terre was pivotal for many of these artists as they rose to prominence following their participation in it. The exhibition itself has also since been the subject of reams of discourse.

Particularly for Huang Yong Ping, this exhibition is special because what started out as a short trip to France saw him moving to France permanently. After Tiananmen happened, Huang decided to stay in France. He became a French citizen, and later represented France in the 48th Venice Biennale. Prior to his move, he made the work The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern Western Art Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes in 1987. The artist pulped two art history textbooks, one Eastern and one Western, in a washing machine for two minutes. In a sense his work already embodied this enmeshing, even before he made that transit from China to France. Having said that, this could be too simplistic a reading as well. As long as the material allows him to think autonomously, I don’t think the artist cares whether bodies of knowledge are purely Chinese or purely French. He’s equally happy to use and reference materials from either culture. He’s very at home with philosophical works and treatises and when I spoke to the artist, certain ideas came up over and over again. Having autonomy, being independent, and being able to think for oneself — these are things that are important to Huang.

If you think about why he pulps books or newspapers, it makes complete sense. After all that knowledge has been digested, these material remains are unimportant. The material is desiccated, and so putting the newspapers through a cleansing cycle in a washing machine is paradoxical. It renders the text meaningless because it can no longer be read. Huang is a huge Ludwig Wittgenstein fan. As I was reflecting on this work more deeply, I kept coming back to a quote by Wittgenstein: “What cannot be spoken must be passed over in silence”. As much as these artists are really interested in text and language, they grew up in an environment where they were told what to do and what to think. In pulping these texts, Huang reminds us that there is a realm of art or cult art that cannot be captured by language. Aesthetics, ethics, things that we hold as meaningful and valuable — these cannot be fully contained by logical language. These things stand outside the realm of science, rational knowledge and politics.

The original artwork was made in 1989, but it was disposed of after the exhibition was over. Reptiles has always been a kind of mythic work that you see reproduced in books and periodicals. The work was reconstructed for the 2013 exhibition, Amoy/Xiamen, at the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon. The new version followed, more or less, the same armature of the original, especially in terms of design and layout. The day’s newspapers are washed in the washing machine, and the pulp is layered onto wired skeletal structures of tombs. The washing machines on display are the exact machines used to wash the newspapers to create the artwork. For the version in Singapore, the wall of paper pulp that runs from the floor to the ceiling was freshly made for the exhibition. We collected local newspapers for Huang, and the interesting thing about Singapore is that you can get newspapers in a variety of languages.

Interestingly from a material perspective, the work does not include any adhesive at all. We were investigating the sort of adhesives that could be used to hold the work together, so we were surprised when the artist told us that glues or external binding agents were unnecessary. This knowledge comes from a deep material understanding of something as basic as newspaper. When you constantly grind or mash paper, its fibres are broken down and it begins to get sticky. This isn’t a magical transformation, but it shows Huang’s masterful grasp of material technicalities.

² Reptiles, Huang Yong Ping

1989, Installation View at Magiciens de la Terre

Credit: Asia Art Archive

1989, Installation View at Magiciens de la Terre

Credit: Asia Art Archive

INSTALLING A MAMMOTH WORK WITHIN A NARROW SPACE

AT: When planning for the exhibition, we were adamant in including a work that spoke to the problematics of language. There were many artists in 1980s China who made works in response to such issues, but we wanted to include works by an artist who engaged with the topic in an intelligent and wry manner. Huang Yong Ping himself is an interesting character. He thinks very deeply about structures — not just social and political, but philosophical ones as well.

This work is currently on loan to us from the M+ Museum in Hong Kong. Every time the work is loaned to another institution, a set of instructions as to how to install the work will accompany it. Reptiles was a late entrant into our exhibition artwork list and exhibition set up. Even though the artwork and its intent is to inconvenience everyone, it still occupies an awkward physical space within the exhibition itself. The tombs in the work have to be arranged along a north-south axis. With narrow gallery rooms, placing the work along this particular axis proved difficult but we managed it eventually.

Furthermore, the artist kindly made some alterations to his installation instructions. Within the installation manual, Huang laid out specifics with regard to the artwork’s orientation, height, length, axis and more. He didn’t have to amend the instructions at all, so it was very nice of him to do that. The only thing he wouldn’t compromise on was the importance of the north-south axis. This has something to do with the way Chinese funerary tombs are sited. The tombs are placed along this axis so as to capture the sun’s movements through the sky, and to optimise preservation of the tomb’s remains. It’s quite scientific, and Huang wanted to follow through with this tradition.

We also had to make some “sacrifices” in order to show this work. There were some works exhibited in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT) iterations of Awakenings that had been shown in previous shows at the National Gallery Singapore. As such, we decided to retire those works for another time. If an artist had two or more works in the exhibition, we tried to reduce that number as well. Showing Reptiles was definitely not insurmountable, especially on a practical level.

³ Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s

Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

Credit: National Gallery Singapore

Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

Credit: National Gallery Singapore

PRESENTING AN EXHIBITION LADEN WITH PERFORMANCE ART

AT: For Awakenings, we display letters, photographs and videos as documentation of quite a few performance works. It is important to remember how artists conceived these documents. They are not a byproduct of an action. They have their own life narratives and complexities. I wouldn’t think of a sketch, a document or a photograph as secondary to the actual performance itself. When we have traces of a performance work, we can revisit these works and take time to think through our own responses. We don’t have an all-seeing eye, so these documents allow us to pick up on details that we might have otherwise missed out.

With performance’s acceptance into the pantheon of art history, it is no longer seen as something provocative. It can sometimes prove more cost efficient to include performances as compared to paying for the shipping, insurance and transportation of a single artwork. We’re also seeing a generation of audiences now that want to be in an immersive environment and for things around them to come alive. Given that, it isn’t actually difficult to talk about curating performances or activating exhibition spaces with performances. We talk about this so often that I think it would be interesting to think about not activating spaces and keeping spaces silent. What would those silent spaces mean?

Although the exhibition is segmented into various chapter, I consider it the merit of this exhibition that it does not have to function with these sections. All the works converse with each other pretty fluently. I also think it is good for audiences to reflect for themselves as to how the work can be understood. It doesn’t matter if there is a “correct” way of viewing these works. Inherent to the realm of art are things that are always going to be ineffable. When people try to impose a single meaning or way of reading, they create the death of art.

The position of the National Gallery Singapore is to respect and privilege the artistic voice, regardless of where an artist comes from. We didn’t set out to create an Asia-centric exhibition or an Asia-centric position. There just haven’t been many exhibitions that examine contemporary art in Asia through a comparative lens. I’m not saying that we did a perfect job in articulating this, but I think that putting these works side by side and letting audiences decide what stands out is a significant gesture. We’re also encountering many things afresh. Prior to working on this exhibition, I hadn’t seen Korean contemporary artworks from the 1970s. It was really refreshing to encounter those bodies of work. Although these works had the finesse of Western conceptual art, they weren’t created by Westerners. That was a moment of reckoning for us, because we need to know that Asian artists were not late onto the global contemporary art scene.

I see this exhibition as a starting point for these discussions. It is the hope of every exhibition to open up visitors’ minds, particularly whatever that was closed before, to new ideas. With Awakenings, socio-political moments are brought to the fore and there is a lot of knowledge to imbibe. Knowing what was going on in the region between the 1960s to the 1990s is important, and I hope this exhibition works helps curb our amnesia regarding this period of time. These days we’re so used to going for art events, art market news, and the celebrity personality of certain artists. We don’t always pay enough attention to the historical context of an artwork — when it was made, how it was made, and how those moments relate to us today. The works exhibited in Awakenings engaged in topics such as freedom of information and gender — topics that are still live today. These works have the potential to really add to the sort of conversations we’re having today as well.

Awakenings: Art in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s is now open.

The exhibition will run at the National Gallery Singapore until 15 September 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

The exhibition will run at the National Gallery Singapore until 15 September 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.