Aki Hassan is an artist. They use drawing and self-publishing as a means to dissect the nonbinary identity and practices of (self)care. This informs and develops into installations of welded and casted objects. They believe in playing with material and objects as a tool, to reflect on the support systems we find ourselves in, as a way to locate strength in the vulnerable.

Aki’s practice spans across sculptural installations, print making, illustration and more. Going beyond the artist as maker, Aki wears various hats such as that of an organiser and co-conspirator. They work alongside like-minded artists to create safe spaces and networks of solidarity for LGBTQ creatives. As two paths seem to diverge in the forest, it becomes clear over the course of this interview that Aki has looked down both as far as they can, and would like to take on both.

Aki’s practice spans across sculptural installations, print making, illustration and more. Going beyond the artist as maker, Aki wears various hats such as that of an organiser and co-conspirator. They work alongside like-minded artists to create safe spaces and networks of solidarity for LGBTQ creatives. As two paths seem to diverge in the forest, it becomes clear over the course of this interview that Aki has looked down both as far as they can, and would like to take on both.

Walk us through your selection of artists and artworks for this conversation. What pulls this collection of works and practices together for you?

This invitation made me realise how vital good photography is in capturing the materiality of the works I chose. I chose quite a few sculptural installations for this interview. When they are presented as images, the experience is transformed into a far more complex one. You can’t have the viewer experience it in the exact same way that I did. When I first encountered these works as images, I found myself attracted to these works in very different ways. For this interview, I picked out works that could capture a certain type of sensitivity and intention. These are works that, I feel, can transform or propose a sort of transformation. Some of these works have also made me feel like they’ve warped time.

It feels like these works are either becoming something or simply just slowing down. That's something that I enjoy a lot in artworks. Some of these installations look like they are stills of a particular moment, yet at the same time, they don’t lose any of the activity. I enjoy works where the interactions between material, object and structures speaks volume.

It feels like these works are either becoming something or simply just slowing down.

¹ armamento memento/espérate un momento, ektor garcia

201

This idea of an artwork having a certain level of activity around about it is something I came across when researching ektor garcia's works. In an interview, he said, “I prefer my work in a state of becoming, alive, growing, begging to be touched, acquiring a patina with age, usage and wearing away.” What do you enjoy about garcia’s works, and what do you make of his views around an artwork as something that’s alive as compared to something that can be “completed”?

I first encountered garcia's work in Glasgow, and it was a really rainy day. I think the way in which you enter a gallery to view an artist’s work makes a huge difference. I remember that the gallery was this huge empty space, and then you suddenly see all these metal bits laid out in the corner of the room. They were laid out in a straight line, and of different shapes and forms. Something about the small, handheld nature of the works made me feel very comfortable around them.

The gallery is, I would say, a commercial gallery. Often with shows in these galleries, you don't necessarily build any sort of relationship with the works on display. When I felt something in encountering garcia’s works, it was just mind blowing. It made me realize that an artist could make work for sale, yet these works could be full of emotional value.

garcia’s work just felt incredibly relatable. I think I enjoy how bodily it was. Something that I think about a lot is how the body is translated. When the body is visualised or transformed into an object. It doesn't necessarily have to be hyper-realistic. It doesn't have to actually mimic how our bodies are. I enjoy that sort of proposal through art. We could be an entirely different being, and we're not stuck in this state of being. That’s why I thought of garcia’s works for this interview, especially because his works are one of the few works that I actually enjoyed being in the presence of.

² Encountering material and object, reflecting on support systems, Aki Hassan

2019, Residency at Pig Rock Bothy

2019, Residency at Pig Rock Bothy

³ a few tolerances, Lauren Gault

2015

⁴ Systems II, Jes Fan

2018

There

is a real palpability around some of the other artworks you’ve chosen, and in

particular I’m thinking of works such as Lauren Gault’s a few tolerances and Jes Fan’s Systems II.

In these two works, I can’t help but think of skin as a

surface or as something that holds other chemicals together. Could you tell us

a little more about why you picked these two works out for our conversation,

and how they’ve left an impression on you?

I haven’t encountered either works by Jes Fan or Lauren Gault in person, but I'm very familiar with their practice. I met Lauren Gault in my first year of university when she came in to do a workshop, which honestly, changed my practice altogether.

I see myself a lot in Jes Fan. I'm still trying to figure out how I can express what I feel in encountering Jes Fan’s works, but I see so much of myself in their practice. I particularly enjoy how bulbous their glass sculptures are. Within my own practice, I enjoy like blowing balloons into metal structures. I think there is some form of familiarity between our works, particularly in how we talk about bodily transformations and trans-ness in art. Jes Fan’s work often features these structures that have organic shapes around them. That's something I really enjoy because it challenges the rigidity of structure. It’s something that I’d like to portray in my work as well — this breaking out of barriers, particularly the barrier of the human body, in order to become something or someone totally different. This is something I get just from seeing his work online. It was just a life changing moment for me to see a trans artist that I could relate to.

Going back to Lauren Gault, I enjoy the fact that her works are not overly reliant on language. When I say language, I'm referring to written language. Lauren Gault allows the materials and objects she uses in her works to speak for themselves, especially in terms of how they interact with each other and their proximity to one another. Often, a viewer might not even notice this. Yet if the viewer does, they become more aware of the activity going on within the space. I enjoy the silence in the activity, especially a silence that can shift into becoming some form of loudness when one realises just how many things are happening all at once. Something that I remember her teaching me was how to build my own vocabularies as an artist with words that I’m just attracted to, or words that I’d want to translate into objects. This is so that they can speak for themselves without you speaking on behalf of them.

That really changed how I approached objects. I now look at objects and materials as things that are capable of making friends or things that are capable of making enemies. For me, it’s about surfacing the relationship and the type of relationship or support system that these objects have with one another. For the longest time, I was obsessed with materials such as plaster powder and clay. This was because of how violent their relationship is. When you mix plaster powder into clay, the clay is known to not be usable anymore. If you mix plaster powder into clay, you're not supposed to fire it. I was really attracted to how silent it was. When I was mixing these materials together, there wasn’t a lot of reaction there. It just felt like they were coming together very well. If you keep playing with or kneading clay and plaster powder, they will slowly merge together and you can no longer see them as separate materials. Yet once it’s placed in the kiln, that's when their relationship becomes a lot more active. That’s what I'm trying to do in my practice. I'm trying to use objects and materials, whether in their raw form or modified, to show this type of activity.

At

the same time, it doesn’t seem like you’re going for an overt portrayal of

activity and motion. What do you think the role of something subtler, such as

the murmurs or echoes of action and movement, is? This is particularly because

I see a lot of tension and tightness within your practice.

There are a lot of layers to this. Firstly, I think my art practice is very much for my nonbinaryhood. I use whatever I make as a point of reflection for where I am in life or how close I am to being open. I have to constantly negotiate and move in and out of being, and to some extent, I think that is translated into my work as well.

There's this possibility of being really loud, but it is almost held back. When you notice a shift or once you notice something that is off kilter, that’s where one might begin relating to my work. I have friends that have an insight to my queerness, and they feel like the work is completely relatable. There is an emotional moment because they can see me for who I am, and that's what I try to do with my practice.

I don't really like playing with images or forms that people find familiar, and this includes referencing pop culture and recreating that in my work. I'm interested in playing with forms, and I'm very selective when it comes to these things. In terms of the forms or motifs that I play around with, a lot of these forms have stayed with me for a very long time. In some cases, they've even transformed or transcended into far more simplistic versions. I used to make drawings of bodies but now I tend to remove certain details. I became less comfortable with using certain body parts to represent who I am.

I was thinking about tension and tightness a lot. I think that’s something that not a lot of people catch when they see my work, even though I think that it’s quite obvious. For me, I would say that it’s up to the viewer to figure out what the tensions are, where they are held, and which objects are holding that.

I have to constantly negotiate and move in and out of being, and to some extent, I think that is translated into my work as well.

⁵ Only Upwards From Here, Aki Hassan

2019, Installation View at 59 Hackney Road

2019, Installation View at 59 Hackney Road

Allowing materials to speak for themselves as compared to having a formal or verbal way of describing them, reminds me of the work you presented at Deviations. When it comes to articulating or describing our lived experiences, we’re so well adjusted to using the verbal. We’re even beginning to get better and better at doing so. Yet having said that, there are some boundaries or limitations to doing so as well. How does it feel like to then use artistic or sculptural language to push the boundaries of spoken language? Has this been productive, freeing, or what sort of places has this experiment brought you?

It’s really interesting because I think about this a lot. Growing up bilingual, sometimes what happens is that you don't necessarily have the right vocabularies to describe certain things. What happened for me is that I ended up not being good at either language. I didn't feel like I could be specific enough in either of the languages. It just felt natural to me to rely on other things to express how I feel or who I am. Even though I’d like to express all of this, I’m really selective about who I open up to or who gets to access how I feel. It’s a privilege to be able to decide who has access to certain things, and when you're able to reach that point where people are able to step into your world to say that they can really see what you’re trying to do — that’s a very, very important moment for me.

I approach my practice in a very nonbinary way. A lot of people relate nonbinaryhood to sexuality or gender, but I bring this thought into my practice a lot. We should not look at materials or practices in binaries. How objects fall into words, how words move into objects, the way objects transform into drawings, the way drawings transform into films — I think all of this should coexist alongside one another. The world is so comfortable with dividing all of us up. I’m not just a sculptor. I make drawings and prints as well. Sometimes, I like throwing people off by including found objects, prints or textiles. It is important that my installations aren’t extracted from their process.

A lot of my installations are, at the end of the day, experimentations of how objects can be pieced together right. The work I presented at Deviations was an experiment for me in thinking about how I could use a wall. The exhibition space was really, really small. I had works that were jutting out to the point where it could potentially endanger viewers, but the curator of the exhibition, Berny Tan, was open to me presenting my works the way they were. On the opening night, visitors had to work around the installation and how the objects confronted them.

When I was making the work, I was thinking a lot about hetero-patriarchy. Being a queer person, you don't necessarily think about certain life things such as marriage or having a lifelong partner. I was assigned female at birth, and the way you’re born can often reduce your future trajectory into being someone that’s just taken care of by a man. When I was making this work, I was thinking a lot about how I had no say in that. Anything that I say in opposition to it is a curse to myself. There’s this phrase “takde jodoh”, which basically means having no fate or not being fated to be with someone. It is usually used in a context of a relationship. People also use the idea of jodoh, which means fate, in other life events. This idea of not having fate just felt more comfortable for me, especially because you’re not linked to anyone and you’re a free person who’s able to choose where your life goes. I used this installation as a playful way of expressing this thought process. I included small kewpie babies within the installation, because something that helps me a lot with making my work is the fact that I think it's funny. To me, the process of piecing things together can be very humorous. I want things that I thought of as incredibly serious or jarring to slowly become things that I can either laugh at or feel alright with. They don't have to weigh on me like baggage.

How objects fall into words, how words move into objects, the way objects transform into drawings, the way drawings transform into films — I think all of this should coexist alongside one another.

There seems to be an element of being almost prankster-ish, but it also

makes a huge statement as to the fact that there aren’t things that are so

sacred you can’t have fun with them.

For sure, but it does not necessarily come across that way to the viewers. I think that that prankster-ish element is something I always keep to myself. It's more of a private moment where I can laugh about cis-normativity and heteronormativity. These systems are so real, and they affect a lot within the LGBTQ community. When you’re trying to survive within these systems, I think every queer person would agree with me when I say that sometimes you just have to have a good laugh about it.

⁶ The artist’s studio desk

⁷ Comic by Esther McManus for Decadence #11

In our earlier email correspondence, you sent me an image of your work desk and studio. Could tell us a little bit about how the process of putting something together looks like for you, particularly regarding the role of sketches and prints — things that we spoke about earlier as showing the process of making — and how they become a huge part of the eventual piece you make.

When I'm in my studio, I actually work on multiple things at once. My workspace is extremely cluttered with different things. I have a very short attention span and I can’t seem to focus on one thing at a time. I think that's why it helps having a multidisciplinary and nonbinary approach to my practice. Knowing that things can coexist with one another, or that things can happen simultaneously, is important.

What you'll find me doing in a studio, usually, is me trying to make a zine, whilst trying to sketch out the dimensions of a metal piece, whilst writing down lists of vocabularies about my work that make sense to me in the moment, whilst also fidgeting with a piece of rope. As a student, I didn’t have a lot of money to buy objects or materials. I’d often walk around looking for objects or found materials to bring into the studio. This process helps me figure out my attraction to certain objects. When you bring a found object into the studio to spend time with it, certain qualities or details begin to stand out. From there, I translate them into my sculptures or casted objects.

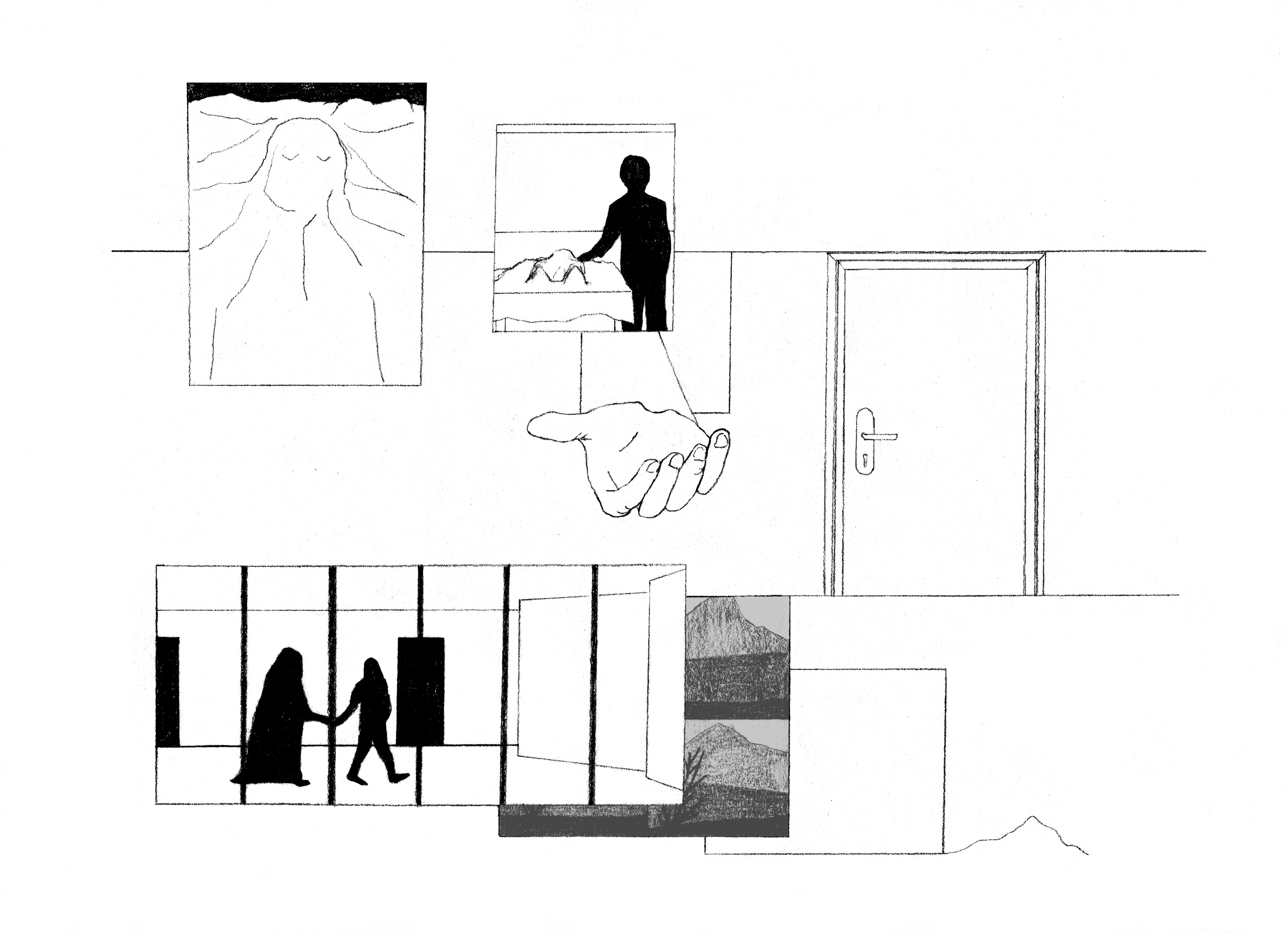

Self-publishing and drawing are key aspects of my practice because this act of collaging or piecing motifs together allows me to see an object’s transformative possibilities very clearly. I’ve also started getting into the comic form. I think a lot of us here in Singapore still see it as a very trivial exercise, but we can learn so much from it. Comics can function as a curatorial exercise, for example, helping us to see how forms relate to one another. I think of the structure of a comic as boundaries that I’m trying to break. It also helps me to think of new forms of boundary making. When you draw a comic, you’re either stuck within the boxes or you erase them completely. To a very large extent, drawing is an incredibly important part of my practice. I cannot make anything without it. It’s a starting point, but it’s also there at every point of the process. With most of my previous installation works, I’ve always included a drawing or a print in them. As I grow, I hope to trust my objects to speak for themselves. I’m also at a point where I’d like to figure out a way as to how I can bridge these two facets of my practice. I don’t like how my practice is seen as either an installations-based practice or an illustrations-based practice. I really want these two facets to sit together.

Tell me about Power Couple Press. How was the press formed, and what is the ethos that steers its operations?

My partner and I started Power Couple Press. We always laughed at this idea of a “power couple”. To me, I can’t relate to it at all. It started off really casually, and we wanted to see where things would go from there. It’s only been a year, but the press has grown so quickly. We started as an in-house thing in Glasgow. My partner, Nat Walpole, and I wanted to do a project where our works could sit alongside other people’s. We’ve always envisioned it as a list of curated works that we enjoy, works that we think say something meaningful. Power Couple Press was an open platform, but we soon realised that we found work by queer artists really important. We wanted to place comics, illustrations and zines by queer artists out there. We wanted to prioritise works that pushed the boundaries of queerness, and works that found different ways of visualising or capturing queerness. For me, Power Couple Press is a space where you can see how works speak to each other and alongside one another.

For the longest time, we’ve always seen Power Couple Press as a Glasgow-based outfit. We never really thought about the possibility of taking things internationally. Now that I’m back here in Singapore, I’m hoping to bring more works by queer, Singaporean artists into the mix.

Something that’s very important to me is how Power Couple Press is run by friends for friends. We’ve worked with people that we weren’t close to at first, but we’ve also eventually become friends. The queer community is so small. You end up meeting each other to support each other. This is super cheesy, but a ‘power couple’ is not just two people. You need a whole community to make a ‘power couple’ happen. Even though Nat and I do most of the work in terms of administration and promotion, at the end of the day, what’s important is that the artists feel comfortable with us. We do our best to be as transparent as possible. We’re not looking to profit off this. It’s just a way for us to be there for the community and to amplify their voices.

The queer community is so small. You end up meeting each other to support each other.

⁸ Power Couple Press at Ghost Comics Fest

⁹ Power Couple Press at ELCAF

⁹ Power Couple Press at ELCAF

The

Covid-19 situation has undoubtedly affected university students, including art

students, around the world. Grad shows, which are meant to be the pièce de

résistance for students’ journey and explorations through art school, are now

going online. Where are you at with parsing through this experience, and what

are your ambitions with regard to what’s next for you?

I’ve been feeling really lost over the past three months. When you’ve been a part of various institutions for so long, it’s obviously disconcerting to now be free of that. The way COVID-19 has affected me and a lot of other students is that it has resulted in us making some really bold career decisions very quickly. I didn’t plan to be making work this soon after my graduation. I had plans to travel and look at art as a viewer and not an artist. For me, I’m thinking about how feasible it is to have an art career here in Singapore without a bread and butter job. Unlike Singapore, Glasgow is comparatively affordable. Rents aren’t as expensive, and I have so many friends who live off online commissions. Not being able to have a taste of that before coming back to Singapore caught me off guard. The reality is that, here in Singapore, you’d need a pool of money to sustain your practice. That doesn’t mean I don’t have dreams. I definitely hope to continue practicing as an artist — with or without a “proper job”.

One day, I hope I’ll be able to bridge self-publishing and installations seamlessly or be known as an artist that works in both realms. That’s something I’d really like to work towards. I don’t want to stop one part of my practice in order to pursue the other. I want them both to coexist simultaneously.

⁸ Being Strong For You / Closeted, Aki Hassan

2020, Installation View at Civic House

2020, Installation View at Civic House