Slow Conversations

Issue: On Re/Discovery

Issue: On Re/Discovery

Anthony Chin (b. 1969) is a designer turned visual artist who holds an MA in Industrial Design from the Royal College of Art. He creates site-specific installations that poetically and conceptually respond to a given site’s architectural presence and history. His works emerge from a process of extensive research, using common materials to invoke particular places with attention to their geopolitical implications and power structures.

Let us start our conversation with a quote by

Mark Twain that you highlighted in our previous correspondence: “History never

repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” Tell us more about how this quote

reflects your understanding of history and how it has motivated your practice.

This popular and humorous maxim about history attributed to Mark Twain has a lot of uncertainty about its ascription. It is a perfect example of how history is inscribed by, as Hayden White writes, interpretation. When historians process information they have researched, they have to go through a level of interpretation. It is like creating a narrative that, in many ways, resembles a fictional story, and it is almost impossible to treat historiography as absolute truth. I do think that history repeats itself, but it almost always comes back in a slightly different form or completely different form. I try to unpack certain power structures by utilising historical narratives—whether it is geopolitics, colonialism, imperial practices, wars, or nationhood. It is, in part, a reaction to having grown up on this tiny little island state, where there is always a sense of vulnerability. We are highly influenced by what happens on the international, or even regional stage. We are constantly affected by it because we are so tiny.

The Republic of Venice existed for only about 1100 years. Even then, it has not been outlasted by any other city-state. My practice is also a way to navigate through this sense of uncertainty and fragility by excavating historical information and understanding the subject of interest through historiography: Why are we in this state? How did we end up here? Who caused it? Who is involved? When did it happen? It's really an attempt at grappling the whole and holding onto something a little bit more concrete.

As an artist, what I am looking for is a point of entry into a subject. That is when I get emotionally affected by what I manage to uncover. Sometimes they are micro-histories that involve a single individual, while other times it might be a much larger piece of narrative that I feel much about. Even in works like Trophy, which is not geographically related to Singapore, my interest was still this unpacking of power structure—how the Philippines was ruled by the US for forty years and how labour was actually exploited as a resource. These are the fundamental interests that I have. Being in Manila gave me an entry point into this particular subject—simply because I was physically there.

¹ Rinnan Steel Mill - INGOT, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at starch

² Rinnan Steel Mill - INGOT, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at starch

² Rinnan Steel Mill - INGOT, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at starch

³ Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History, Chin Peng

³ Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History, Chin Peng 2003

In relation to micro-histories, I am thinking

about one of your recent works shown at the RECAST exhibition. The work is about two Japanese soldiers, Tanaka and Hashimoto. By

creating these individual narratives, what did you hope to explore in this

work?

I stumbled upon Tanaka and Hashimoto when I was reading Chin Peng's autobiography, Alias Chin Peng: My Side of History. In the book, he writes that hundreds of Japanese civilian and military personnel joined the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) after World War II. I embarked on that research to get a better understanding of that postcolonial Malayan Emergency period, which also overlaps with the Japanese invasion. My attention was drawn to Chin Peng because the dominant Cold War narratives about the struggle between the US and the USSR can feel very detached from our contexts because of the British presence in Singapore. I also wanted to understand the Malayan Emergency.

When I stumbled upon Tanaka and Hashimoto, I went quite deep into the research. I hired a translator to translate academic papers that were only available in Japanese. We knew that World War II was about natural resources, but there were other motivations, especially for the Japanese. Some discoveries took me away from the well-known narrative about the colonial British exploitation of Malayan natural resources, namely rubber and tin. To me, iron ore is way more important, and the study of this resource has been neglected in most of the history of our region. The extraction of iron from Malaya started in the 1920s, and it was mostly carried out by the Japanese. This information only surfaced as recently as ten years ago, and this is partly due to the classification of historical records. Through that process, I managed to link the two Japanese soldiers to an imperial need for iron ore and steel resources. Iron and steel were needed for modernisation and for the preparation of war. There was also the sad realisation that invading weapons like shin guntō, a mass-produced Japanese military sword, and many other heavy-duty weapons were highly likely made using material extracted from Malaya. Rinnan Steel Mill has become a long-form project that I will continue to explore, and it is named after the mill in Malaya that Tanaka and Hashimoto worked at before and during the war.

The research into this period was an attempt at understanding the immediate years before the formation of our nation and the region, as well as the stories that sit on the peripheries of the larger canon of history. Oftentimes, I realise that personal stories can link back to a larger narrative. In a small way, I'm asking existential questions, specifically in the two works under Rinnan Steel Mill. I am asking questions about how natural resources were deployed when they were deployed, and why such transformation happened. Most importantly, I am also asking how and why they eventually became a tool of violence. Tanaka and Hashimoto embody the geopolitical tensions through that period and the ironic travel of this natural material—even though they are two single individuals. Hence, the work addresses micro and macro discoveries simultaneously. However, my real interest is in revealing power structures, simply because it is affects almost all of us—and this does not always involve historical events.

The research into this period was an attempt at understanding the immediate years before the formation of our nation and the region, as well as the stories that sit on the peripheries of the larger canon of history. Oftentimes, I realise that personal stories can link back to a larger narrative.

⁴ Rinnan Steel Mill - GRIND, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at starch

⁵ Rinnan Steel Mill - GRIND, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at starch

⁵ Rinnan Steel Mill - GRIND, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at starch

I was fascinated by the idea of material

transformation explored in several of your works that were shown in the

exhibition, RECAST. This ranges from

turning water to ice, changing sword to dust, and transforming sweat to salt.

Given your background as a designer, what would you say your approach to

materials and object making is?

I was a practicing designer in both product design and graphic design for over fifteen years before I took on the fine arts in a serious way. I've been exposed to various influences and gained some knowledge in object making by understanding material and how things are made. Having said that, I am also interested in how material can be approached in other surprising ways. Sometimes it is also driven by pragmatic needs. For example, the decision of converting sweat into salt in Trophy was made to emphasise the poetry within the work, but also to ensure the ease of presentation—the concern is that a bucket of sweat may be considered a biohazard. If the transformative process does not add to what I feel about a subject, I will not alter an object or material. There is no fixed formula.

From time to time, I subconsciously step into being a designer. It is a part of me that I cannot negate. I feel that materials and objects have symbolic meanings attached to them. For example, a watch that your grandfather left behind will contain many layers of attached sentiment and personal stories. It is no longer a simple tool that is used for keeping time. If we expand on this to consider a brick that used to be part of the Berlin Wall, a different image will emerge. I believe my manner of imagining symbols was largely influenced by Achille Castiglioni. He was a legendary Italian product designer. Inspired by Marcel Duchamp, Castiglioni incorporated readymade objects into some of his designs. His interest was in the irony attached to such readymade items. Although I don’t use readymade material and objects in the same way, Castiglioni’s approach has partially informed my way of looking at them.

From time to time, I subconsciously step into being a designer. It is a part of me that I cannot negate. I feel that materials and objects have symbolic meanings attached to them.

Let's talk more about your research process.

In our last conversation, you mentioned that the idea of casting that rock for

your work, Air Doa Selamat, came from

a specific discovery. Can you tell us more about how you translated your

research into the material form that we see now?

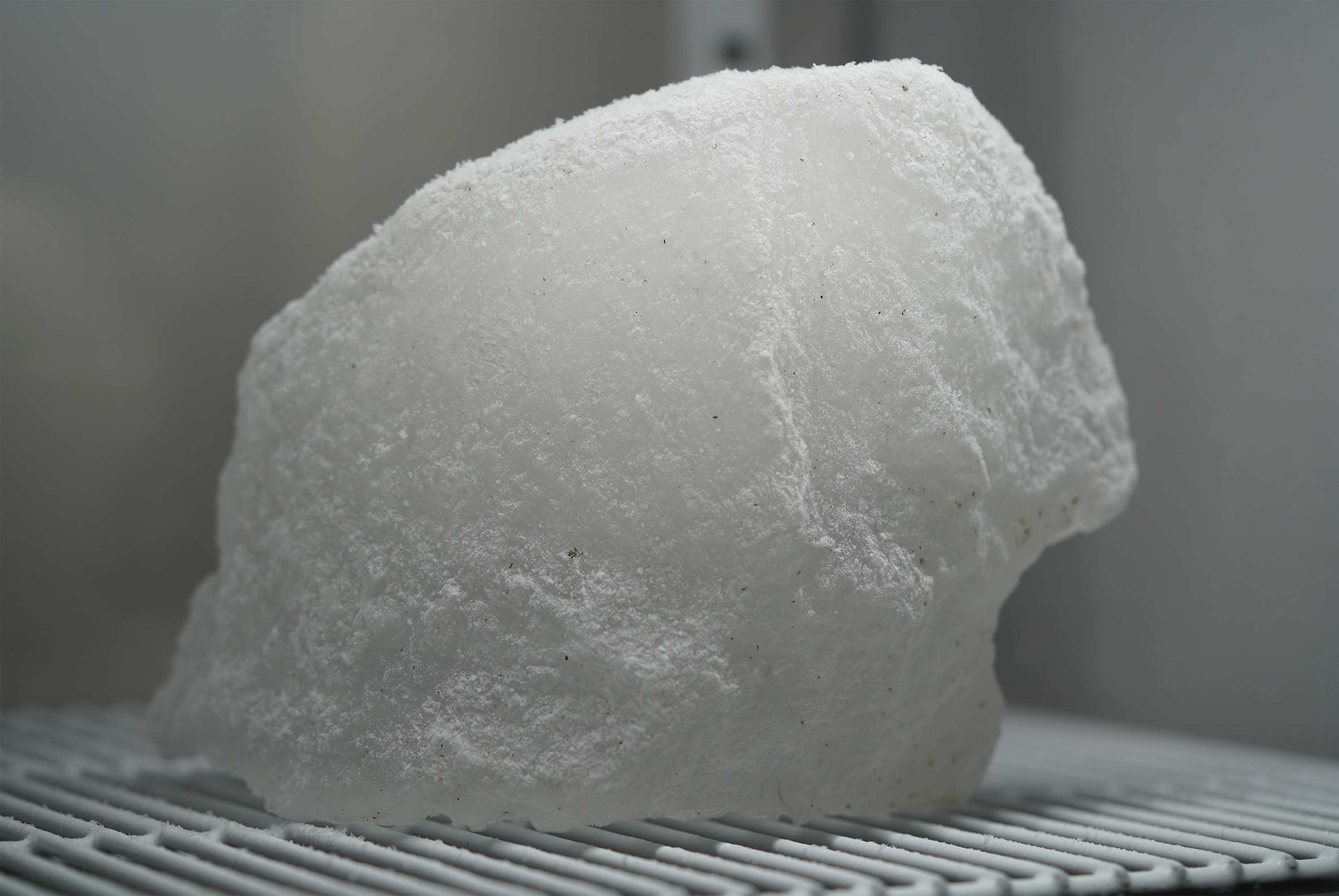

My research reveals that the colonial British administration's decision to exploit Pulau Ubin’s granite formations to provide rubble for the Johor–Singapore Causeway, was pushed by their lack of funds to build a proper bridge, due to World War I. The Causeway took about two thousand laborers and used 2 million cubic tons of Pulau Ubin granite. That is why there are now deep quarries in Pulau Ubin that are filled up with rainwater. I retraced this journey by collecting rainwater from a quarry at Pulau Ubin and a granite rock from the Causeway. Air Doa Selamat brings together the characteristics of granite and rainwater found in the quarries’ cavities. This is blended into an allegorical image that is associated with the Causeway. After using the rock to create a silicone mold, the rainwater was frozen. The ice block is seemingly solid, but is actually extremely fragile in our tropical climate. The effort that goes into trying to maintain its form is conceptually crucial—that's why its original cast still sits in my fridge, even when it is not exhibited.

I’ve created a number of other works around the subject of Singapore-Malaysia relations, and similarly, Air Doa Selamat grew out of the fact that the Causeway embodies the connection to my relatives and friends in Malaysia. When I was a kid, traveling over the Causeway in my Dad's car to visit relatives was a major highlight. Whenever I’m in Malaysia, the separation always felt surreal because we actually are very similar. Yet we belong to two different national entities. Personally, I still hope that we can somehow become one again. This is why my wish is that the foundation of the Causeway remains strong and dependable, much like the granite that was used to build it. However, the reality is that the longer we stay as two separate entities, the further we drift apart from one another. To reflect this, the block of ice will eventually sublimate over time, even if it remains constantly frozen.

⁶ Air Doa Selamat, Anthony Chin, 2020, Installation View at starch

⁷ Air Doa Selamat, Anthony Chin, 2020, Installation View at starch

⁷ Air Doa Selamat, Anthony Chin, 2020, Installation View at starch

Besides the transient nature of the material

itself, your work also explores the human labour and resources that go into

preserving the material form of an (art) object. How does this symbolism of

collective efforts relate to your interest in the idea of nation-building and

instruments of authority?

A nation really is the sum of all the individuals that reside within that constructed landmass and its clearly defined boundaries. Without the people, nations don't exist. Labour is needed in every single aspect of nation-building. Having awareness and a realisation about one's involvement in that process can help to inform an individual’s decisions and actions. Labour, as expressed in my work, Trophy, can be exploited. That particular work deals with imperial hegemony and reduces human labour into another form of natural resource. Through something as simple as sport and a trophy, people can be mobilised for certain costs. My focus in this is on self-determination—not nationalistic self-determination, but the freedom of self-determination. That would entail understanding and knowing your rights to choose, and having a right to choose. Prior to the construction of nations, kingdoms and dynasties were the power and authority for thousands of years. The concept of nation is still an experiment. We don't know how that's going to turn out, but for the lack of other alternatives, I think that's something that we are stuck with for a while.

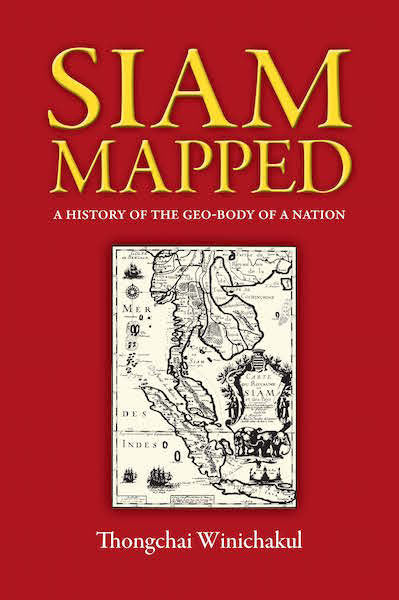

⁸ Siam Mapped, Thongchai Winichakul

1994

What motivates these questions about the

construct of the nation, and how have these ideas shaped your research and your

practice?

One of my biggest takeaway from the book by Thongchai Winichakul, Siam Mapped, is that the concept of nations is not really ideal. The idea of a nation is binary by nature. It is based on the existence of me, and therefore an inevitable you. There is a rather Buddhist way of looking at this concept of selflessness, which manifests very clearly in the book. I think that is why I connected with the book’s ideas quite strongly. Winichakul’s study of maps and modern cartography is very enlightening. I read Siam Mapped right after reading Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson. Anderson also attempts to reveal the apparatus of nation-building by examining the importance of languages, symbols, technology, and commerce. These two books shed so much light on the subject. I cannot help but feel a sense of rootlessness because the nation really is a fictitious construct. It is held together by an abstract belief that has been built into every individual’s psyche. We don't know most of the people within a so-called nation, and we only know our immediate friends and relatives. To me, that feels pretty precarious. That might also explain my interest in working with transient material.

I cannot help but feel a sense of rootlessness because the nation really is a fictitious construct. It is held together by an abstract belief that has been built into every individual’s psyche.

⁹ S$1,996/-S$831.06, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at Comma Space

¹⁰S$1,996/-S$831.06, Anthony Chin, 2021, Installation View at Comma Space

¹⁰

Let’s direct our conversation to your new

work: S$1,996/-S$831.06. It challenges the relationship

between art and funding, as well as the involvement of the public. Can you tell

us more about your consideration behind this method of crowdfunding and the

compositional choice of this piece?

The title is complicated because it responds to the outcomes of this attempt to obtain funding for a show and a work. The project is a process, and looks at the value of art, artists and our sustainability? The project started with a two-hour conversation between the curator, Michael Lee, and me. The conversation was dominated by the need to meet an art fund application that was, at the time, closing in two weeks. The reality of putting in application after application for funding whilst not knowing the outcome naturally became a weight. This is what most artists in Singapore have to deal with. In response to this uncertainty in the process of applying for funding, I decided to look at the macro environment—where 80% of all art funding in Singapore comes from the government. How does that affect artists who operate within this ecosystem? In comparison, our immediate neighbours regionally have almost no government funding for the arts. That void is filled up by influential patrons and collectors, which creates a different form of power dynamics.

The idea was to use material or media that directly expresses value. By utilising the money available for funding, I set out to enlarge the physical dimensions of the material, therefore expanding the dimensions of the final work. The concept was to convert the funding into legal tender—Singapore one-dollar coins—and to use the coins as material for a pillar that goes from the floor to the 4.4-metre-high ceiling. It was built using coins that were stacked, one on top of another, forming a golden column that masquerades as a structural, architectural element.

The application we put in for funding was eventually rejected, but I was determined to realise the work by exploring alternative avenues of funding. Finally, a donation drive from friends and families was called. I had hoped to raise 1,996 one-dollar coins, because that's the exact number of coins needed to build the 4.4-metre pillar. The donation drive eventually closed with a total tally of $831.06, which explains the work’s title. With that, an incomplete pillar was built. It is suspended within the space between reflective steel tubes. There is a continuation of the material used to make the one-dollar coins and the steel pole that is supporting the work. I was hoping to look into that relationship between a steel pole, which costs a certain amount of money to fabricate, and a single one-dollar coin, which one assumes is worth S$1.

If you look at the exhibition publication, the medium of the work is stated as: Unsuccessful art grant application, below target donation drive, S$1 coins, adhesive, and steel. Various mechanisms were employed to create this circular mode of creation, and you wouldn’t see this by looking at an installation. In the application we submitted for government funding and support, we made it clear that, if successful, I would donate my artist’s honorarium back to the funding body. Yet, artists, curators and independent exhibition spaces need money to sustain their work. To achieve that, the work is available for purchase. The sales proceeds will be split equally between the three parties—the curator, Comma Space, and myself. Will the work ever be sold? We don't know. In essence, it is about dealing with that unpredictability and questioning what determines artistic value. It is a very, very old question of which I have no new answers.

What is your view on the value of artistic

research in our contemporary society? Do you think artists can help the public

understand or re/discover the constructed-ness of our multilayered reality?

This is a very broad question, to which I can only give you a very short answer. I see artistic research as something personal. Every artist has their way of working, and their way of responding to various subjects. I simply enjoy the process of unearthing what I don’t know. To me, artworks that respond to certain existential realities—even if partially fictional or incomplete—have a certain sense of urgency embedded within them. This is my way of searching for an entry point. These artistic expressions are opportunities for me to participate in these conversations. I don't think of it as a responsibility or duty. I think of it as a process of looking for things, and sharing what I found with others. It is up to the public to look closer at it or find out more. History is often fictitious. What I state through my works may not be 100% truthful because their very sources are questionable.

I just do what I like, and put forward what I've discovered. My hope is that the works are good enough and could propel people to dig deeper into what inspired those works. As an artist, I think that's all an individual can do.

History is often fictitious. What I state through my works may not be 100% truthful because their very sources are questionable.