“To change the written word, is to strike at the very foundation of a culture.”

— XU BING Xu Bing was born in 1955, and spent his formative years in the hallowed halls of Peking University. His parents worked at the university — his mother a librarian and his father a historian — allowing him to spend much of his childhood in the Peking University library. Xu grew up surrounded by academics and was an introverted child. He enjoyed drawing, but worked slowly. The drawings he made won him high praise, and this motivated him to continue pursuing art. However as the Cultural Revolution swept through China, his family, like so many others, was torn apart. Branded a reactionary by the government, his father was imprisoned. Xu himself was sent to a remote village after finishing high school. There, he worked with farmers and did manual labour for three years. When he was able to return to Beijing, he enrolled in the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) and studied printmaking. During this time, Xu was assigned to the propaganda division due to his skill in calligraphy.

During the cultural revolution, art production was tightly controlled. It was used as a tool for propaganda, and only art that glorified the Cultural Revolution was sanctioned by the state. The Communist Party of China’s attitudes towards art and culture were clearly explicated during the Yan’An Forum on Literature and Art. At the forum, Chairman Mao spoke at length as to the place of art in Communist China. Mao’s speech was concerned with who the audiences for art were – it must be for the people. Yet when we consider who art serves or is enjoyed by, who are these “people”? There is an in-group and out-group generated as such — those who can be considered the “people” and those who cannot. It follows then that maxim, “Art for the People”, does not have its literal meaning. While the literal meaning is one of inclusivity, the actual meaning delineates specific audiences of art. This resulting disparity between one’s expectation and the situation’s reality is something that is repeatedly mirrored in Xu’s work. This is particularly evident in his 1999 piece, Art For The People, which takes its title from a quote in Mao’s speech.

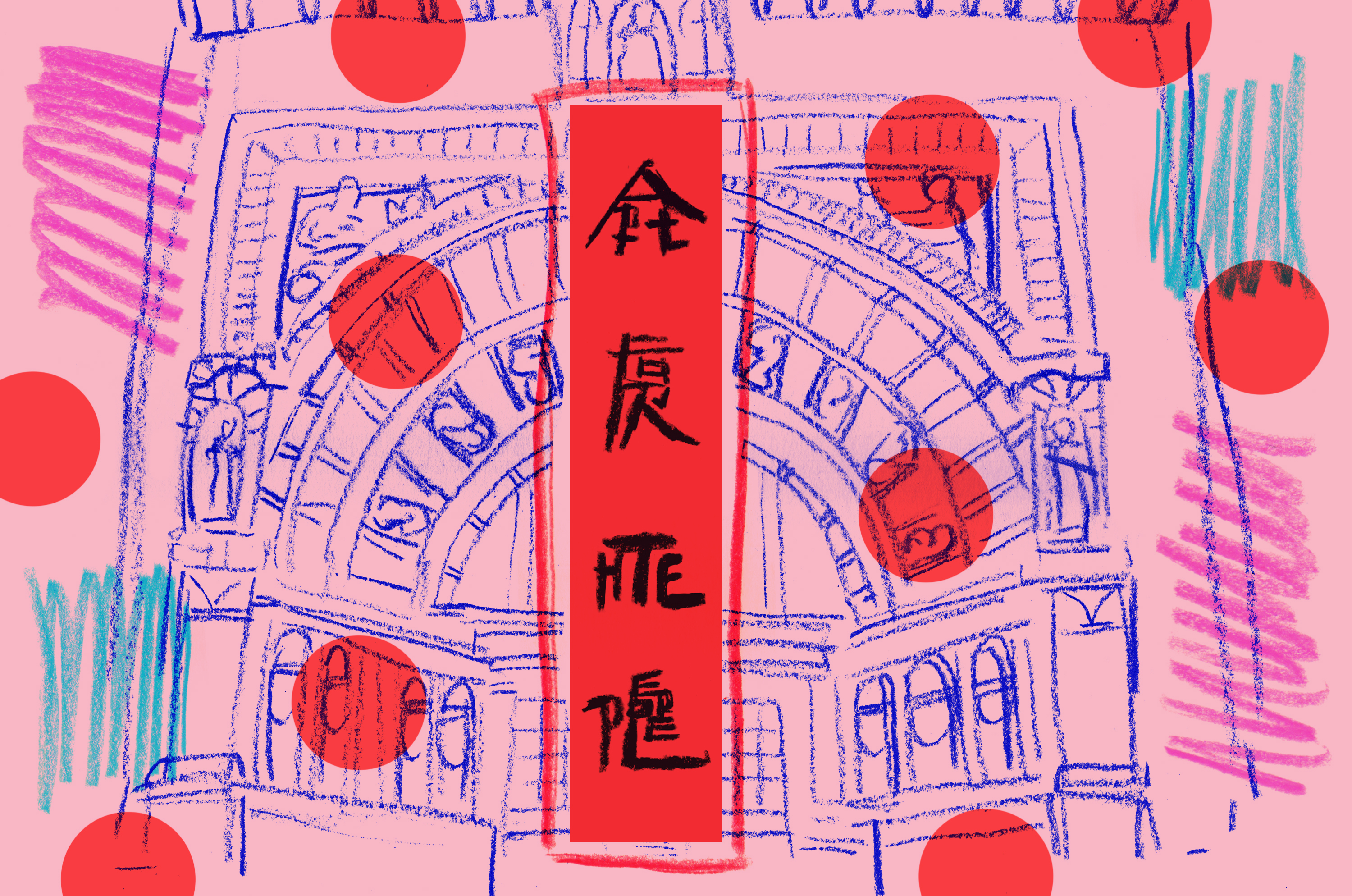

Art for the People was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for Project 70: Banners, an exhibition under the Projects series. This series was created with the dual intention to provide more opportunities to emerging artists and junior curatorial staff, as well as to introduce avant-garde pieces to a museum context. Many of the works exhibited under this series were displayed in places in the museum that were less conventional, for instance in the museum café and, as with Project 70: Banners, along the façade of the building. Art for the People could not have debuted at anywhere more apt — at the entrance of the museum in an open, un-ticketed space, alongside the museum’s logo. In this way, it acts as an almost-slogan to a museum, a public space in which art is patrimony of the people and not merely of the elite.

During the cultural revolution, art production was tightly controlled. It was used as a tool for propaganda, and only art that glorified the Cultural Revolution was sanctioned by the state. The Communist Party of China’s attitudes towards art and culture were clearly explicated during the Yan’An Forum on Literature and Art. At the forum, Chairman Mao spoke at length as to the place of art in Communist China. Mao’s speech was concerned with who the audiences for art were – it must be for the people. Yet when we consider who art serves or is enjoyed by, who are these “people”? There is an in-group and out-group generated as such — those who can be considered the “people” and those who cannot. It follows then that maxim, “Art for the People”, does not have its literal meaning. While the literal meaning is one of inclusivity, the actual meaning delineates specific audiences of art. This resulting disparity between one’s expectation and the situation’s reality is something that is repeatedly mirrored in Xu’s work. This is particularly evident in his 1999 piece, Art For The People, which takes its title from a quote in Mao’s speech.

Art for the People was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for Project 70: Banners, an exhibition under the Projects series. This series was created with the dual intention to provide more opportunities to emerging artists and junior curatorial staff, as well as to introduce avant-garde pieces to a museum context. Many of the works exhibited under this series were displayed in places in the museum that were less conventional, for instance in the museum café and, as with Project 70: Banners, along the façade of the building. Art for the People could not have debuted at anywhere more apt — at the entrance of the museum in an open, un-ticketed space, alongside the museum’s logo. In this way, it acts as an almost-slogan to a museum, a public space in which art is patrimony of the people and not merely of the elite.

¹ Art For The People, Xu Bing

1999, Installation View at the Museum of Modern Art

² Art For The People, Xu Bing

1999, Installation View at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art

1999, Installation View at the Museum of Modern Art

² Art For The People, Xu Bing

1999, Installation View at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art

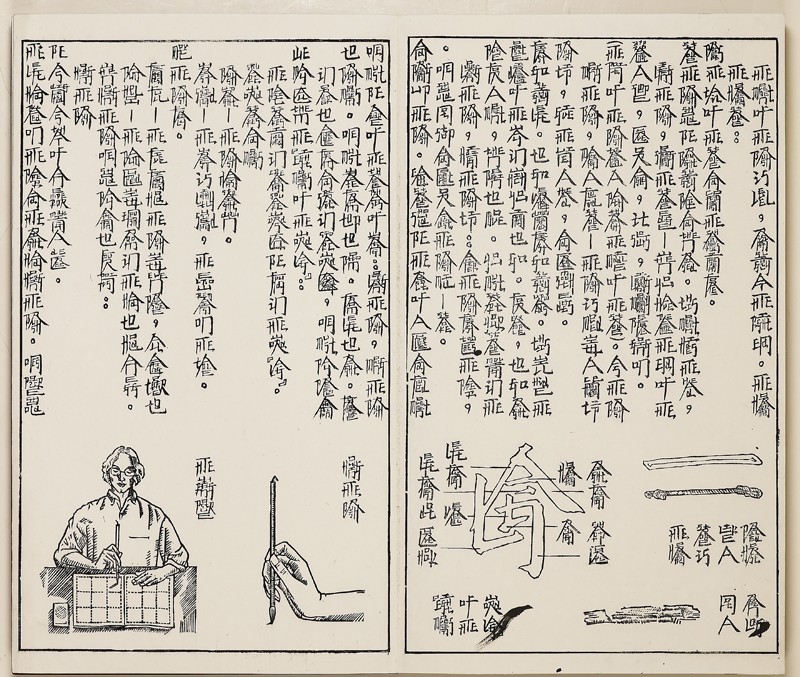

The proclamation on Art for the People was written in Xu’s invented writing system, Square Word Calligraphy. The symbols in Square Word Calligraphy resemble Chinese characters in form, but they actually comprise of English letters. Xu offers Art for the People as a message of reconciliation to a public he believes to be alienated by contemporary art. To an English speaker, the strangeness and exoticism of the Chinese form can be understood as a metaphor for contemporary art. To an outsider, the contemporary art world is full of gatekeepers that stand guard over knowledge, history and access points. Yet upon a closer look, it is a familiar language that is presented in a different way. With some attention, the work unravels and meaning can be found. Xu’s desire to challenge his audience to re-examine “ingrained thinking patterns” can be accomplished. To the bilingual English and Chinese speakers, this is also possible in that they are able to perhaps bridge a gap in the two aspects of their identities.

In other words — to be part of the “people” or the work’s intended audience, one needs to be fluent in English. While that, perhaps, is not an absurd or unreasonable assumption to make of an audience in New York, where the operating language is English, it becomes slightly uncomfortable when considering how a monolingual Chinese speaker may have to interact with this work.

Art for the People, for all purposes, appears to be inescapably Chinese. The red and yellow colour scheme bears resemblance both to the Chinese flag and the traditional Chinese spring scrolls. These scrolls are usually displayed vertically at the entrance of a building, and take the form of red banners with text written in either black or gold. The effects are such that it is immediately recognisable as Chinese, to the average New Yorker or to the first-generation Asian American immigrant who may have seen it in person on the 53rd Street in midtown Manhattan. However, from here familiarity departs. Although the words look Chinese, they are not. They concede to the lingua franca of today’s world and are familiar only on the surface. The “Chinese-ness” of the work ends at its appearance, and it leaves a Chinese-speaking audience in a state of confusion.

In other words — to be part of the “people” or the work’s intended audience, one needs to be fluent in English. While that, perhaps, is not an absurd or unreasonable assumption to make of an audience in New York, where the operating language is English, it becomes slightly uncomfortable when considering how a monolingual Chinese speaker may have to interact with this work.

Art for the People, for all purposes, appears to be inescapably Chinese. The red and yellow colour scheme bears resemblance both to the Chinese flag and the traditional Chinese spring scrolls. These scrolls are usually displayed vertically at the entrance of a building, and take the form of red banners with text written in either black or gold. The effects are such that it is immediately recognisable as Chinese, to the average New Yorker or to the first-generation Asian American immigrant who may have seen it in person on the 53rd Street in midtown Manhattan. However, from here familiarity departs. Although the words look Chinese, they are not. They concede to the lingua franca of today’s world and are familiar only on the surface. The “Chinese-ness” of the work ends at its appearance, and it leaves a Chinese-speaking audience in a state of confusion.

³ An Introduction to Square Word Calligraphy, Xu Bing

Ashmolean Museum, 1994-1996, Detail

Ashmolean Museum, 1994-1996, Detail

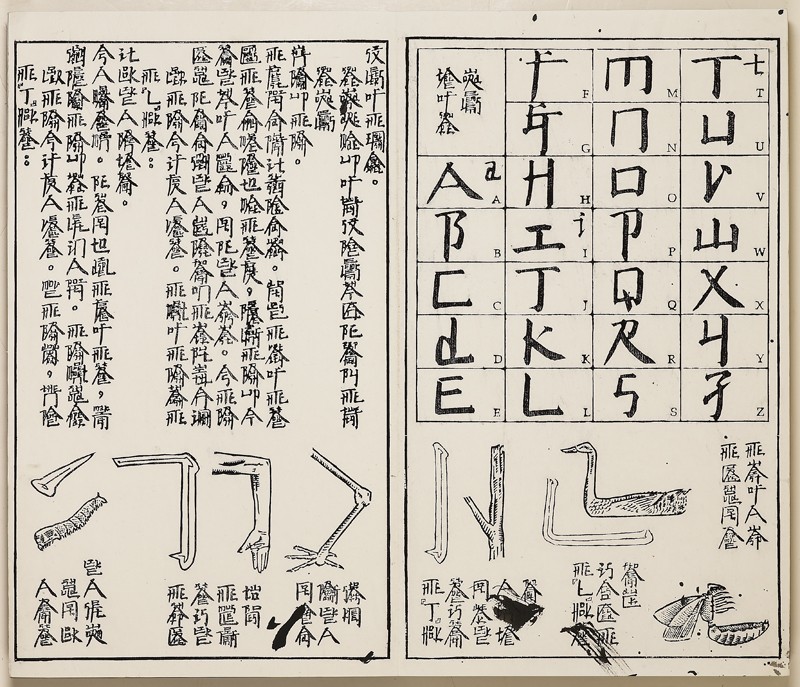

This sense of confusion finds echoes in another work of Xu’s, Book from the Sky (天书). This work was first shown at the 1989 China/Avant-Garde Exhibition at the National Art Museum of China. This was an exhibition that defined, in many ways, the shape and form of modern Chinese art. Book from the Sky is a site-specific installation piece. Long scrolls of paper are hung from the ceiling, suspended over bound, scholarly-looking volumes flipped open on a low platform. Surrounding this centre display are large posters hung on the walls. Xu had devised a “writing system” for this work as well, spending two years designing and carving out some four thousand Chinese-looking but ultimately nonsensical characters. In a previous interview, he explains a typical Chinese text would comprise about four thousand different characters. As such, one would be considered proficient in the Chinese language if they could recognise four thousand characters. The work touches on similar ideas of literacy and completeness. Should audiences be capable of deciphering these symbols, the four thousand characters in Book from the Sky present a language, and thereby reveal a complete meaning.

Yet, meaning is exactly what eludes the viewer. For Chinese viewers, the impact is heightened and pronounced. There is almost a sense of betrayal when the language, at first glance so familiar, reveals itself to be unrecognisable. The presentation of the script suggests knowledge, both ancient and wise, that could be uncovered. Yet, this knowledge and its meaning escapes the viewer. There is a sense of loss; the viewer is undermined, suddenly rendered illiterate. The work is whole, complete ecosystem with four thousand characters. The fault lies not in the work but with the viewer.

Even to the mark-maker, the designer, carver and printer, Xu himself, the characters are meaningless. This echoes his own experiences growing up and living through the Cultural Revolution. In the Peking University Library, he was old enough to know the promise of knowledge held within the characters, but was too young to understand; during the Cultural Revolution, despite being the very maker of the posters and slogans, Xu did not own the meaning of the words. One’s relationship to the language is almost irrelevant.

Yet, meaning is exactly what eludes the viewer. For Chinese viewers, the impact is heightened and pronounced. There is almost a sense of betrayal when the language, at first glance so familiar, reveals itself to be unrecognisable. The presentation of the script suggests knowledge, both ancient and wise, that could be uncovered. Yet, this knowledge and its meaning escapes the viewer. There is a sense of loss; the viewer is undermined, suddenly rendered illiterate. The work is whole, complete ecosystem with four thousand characters. The fault lies not in the work but with the viewer.

One’s fluency in their own language is transformed into a pseudo-language, where meaning dances at the edge of one’s fingertips, just out of reach.

Even to the mark-maker, the designer, carver and printer, Xu himself, the characters are meaningless. This echoes his own experiences growing up and living through the Cultural Revolution. In the Peking University Library, he was old enough to know the promise of knowledge held within the characters, but was too young to understand; during the Cultural Revolution, despite being the very maker of the posters and slogans, Xu did not own the meaning of the words. One’s relationship to the language is almost irrelevant.

⁴ Book from the Sky 1987–91, Xu Bing

1987-1991, Installation View at Blanton Museum of Art

1987-1991, Installation View at Blanton Museum of Art

In Art for the People, language becomes relevant again. One must be literate in English in order to understand the work.

Perhaps an optimist would say that the writing, by being in the global lingua franca, can reach a wider audience than otherwise, thereby expanding the definition of the “people”. However, it would be disingenuous and unfaithful to its roots as this writes off the audience that comes from the artist’s own background, culture and history.

Since Art for the People was unveiled at the MoMA, countless scores of Chinese children have been made to learn English in order to fit into and be competitive in a globalised world of Western economic and cultural dominance. The varying degrees of success to which this has been achieved makes this work especially poignant. The Chinese language is not considered to be as precious or valuable as English, certainly not then and perhaps still not now. Square Word Calligraphy may even be considered to be an example of commodifying Chinese culture to be profitable and appealing to a Western audience, in the same vein as Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern, which won the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and Ang Lee’s Crouching Dragon, Hidden Tiger which won an Academy Award.

Art for the People ironically limits understanding. The words, about making art accessible to everyone, ring bright but are empty. The work lacks the powerful unifying factor evident in Book from the Sky, and seems almost cavalier in light of its exclusion of meaning to the very people whose language it takes its shape from. Absurdly enough, this perhaps still functions well as a metaphor for contemporary art, just as Xu intended. The work conveys something inaccessible by definition, coded in somebody else’s system of meaning. To the monolingual Chinese speaker, the work is not reconciliatory. It merely represents the alienation that is the relationship between contemporary art and the public.

When we speak of making art for the people, who are these “people”? How effective is the message if the audience is limited to those who can read and write in English?

Perhaps an optimist would say that the writing, by being in the global lingua franca, can reach a wider audience than otherwise, thereby expanding the definition of the “people”. However, it would be disingenuous and unfaithful to its roots as this writes off the audience that comes from the artist’s own background, culture and history.

Since Art for the People was unveiled at the MoMA, countless scores of Chinese children have been made to learn English in order to fit into and be competitive in a globalised world of Western economic and cultural dominance. The varying degrees of success to which this has been achieved makes this work especially poignant. The Chinese language is not considered to be as precious or valuable as English, certainly not then and perhaps still not now. Square Word Calligraphy may even be considered to be an example of commodifying Chinese culture to be profitable and appealing to a Western audience, in the same vein as Zhang Yimou’s Raise the Red Lantern, which won the BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and Ang Lee’s Crouching Dragon, Hidden Tiger which won an Academy Award.

Art for the People ironically limits understanding. The words, about making art accessible to everyone, ring bright but are empty. The work lacks the powerful unifying factor evident in Book from the Sky, and seems almost cavalier in light of its exclusion of meaning to the very people whose language it takes its shape from. Absurdly enough, this perhaps still functions well as a metaphor for contemporary art, just as Xu intended. The work conveys something inaccessible by definition, coded in somebody else’s system of meaning. To the monolingual Chinese speaker, the work is not reconciliatory. It merely represents the alienation that is the relationship between contemporary art and the public.

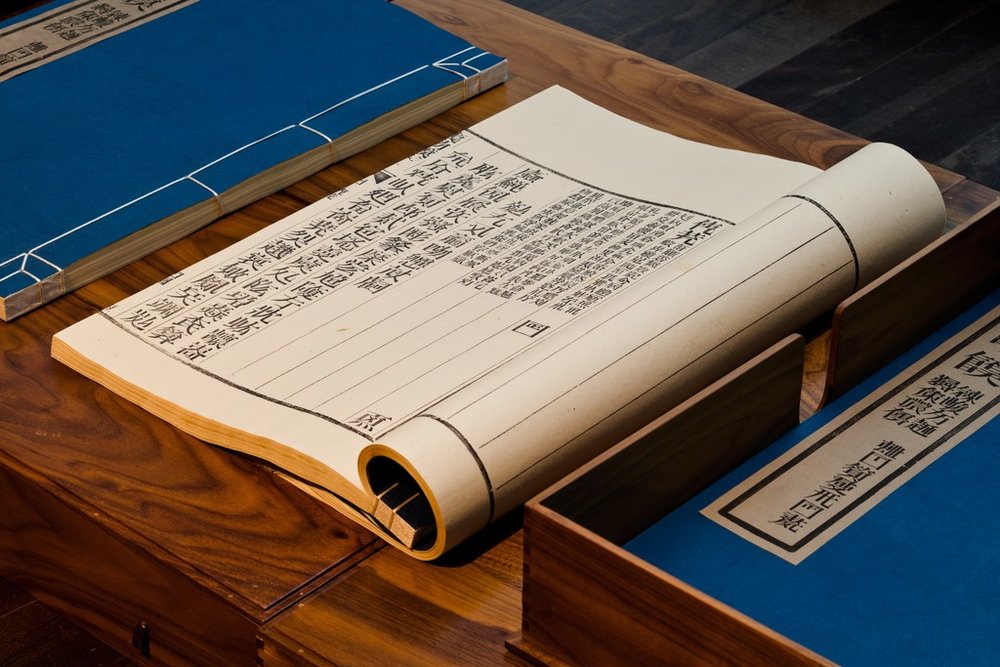

⁵ Book from the Ground, Xu Bing

2003-ongoing

2003-ongoing

His original intent in may be better fulfilled in a more recent work, Book from the Ground. It stands in diametrical opposition to the Book from the Sky, which was created twenty years prior. Book from the Ground is a graphic novel composed of symbols and icons that are universally understood. As these symbols have been adopted and used by cities and communities all around the world, Xu intended for this work to be legible to all who were familiar with these systems. The symbols used in these works have also been used on signboards, posters, instruction manuals, and more. In evoking a universal visual language, Xu eliminates the need for specific cultural knowledge or literacy in a certain language when encountering art.

To pay homage to his past works, Xu’s studio made a character database software which translates English or Chinese to this new visual language — a compelling ode to the languages he has worked in over the years. An accompanying book, The Book about Xu Bing’s Book from the Ground, has also been published. It serves as a guidebook for audiences, with translations and interpretations of these symbols.

Through these three works, it is clear that Xu Bing’s body of work comments on audiences and meaning by experimenting effectively with the written word and literacy. Art for the People represents Xu’s intent and beliefs. It preaches a message of accessibility, but inadvertently draws attention to the precariousness of inclusivity, and to barriers of literacy which may limit the audiences of a work. Book from the Sky and Book from the Ground respectively alienates and unites its audience as a whole, with the latter finally able to offer meaning to a universal audience. The relevance of Xu’s works cannot be understated. His works have been the subject of countless retrospectives, such as Xu Bing: Thought and Method at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art and at Museum MACAN. As the artist continues to question language systems and points of accessibility, his works will continue to engage and enthral audiences with both its inventiveness and insight.

To pay homage to his past works, Xu’s studio made a character database software which translates English or Chinese to this new visual language — a compelling ode to the languages he has worked in over the years. An accompanying book, The Book about Xu Bing’s Book from the Ground, has also been published. It serves as a guidebook for audiences, with translations and interpretations of these symbols.

Through these three works, it is clear that Xu Bing’s body of work comments on audiences and meaning by experimenting effectively with the written word and literacy. Art for the People represents Xu’s intent and beliefs. It preaches a message of accessibility, but inadvertently draws attention to the precariousness of inclusivity, and to barriers of literacy which may limit the audiences of a work. Book from the Sky and Book from the Ground respectively alienates and unites its audience as a whole, with the latter finally able to offer meaning to a universal audience. The relevance of Xu’s works cannot be understated. His works have been the subject of countless retrospectives, such as Xu Bing: Thought and Method at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art and at Museum MACAN. As the artist continues to question language systems and points of accessibility, his works will continue to engage and enthral audiences with both its inventiveness and insight.

REFERENCES:

¹ Bloomberg. “Intellectual by Nature, Poet at Heart: Xu Bing | Brilliant Ideas Ep. 15.” Filmed November 2015. Youtube Video, 24:10. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jxHWJjaUDQg&t=16s.² BLOUIN ARTINFO. “AI Interview: Xu Bing.” Filmed April 2012. Youtube Video, 5:33. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7ioUyG1gSs.

³ Daftari, Fereshteh. Projects 70: Banners (Cycle 1): Shirin Neshat, Simon Patterson, Xu Bing: the Museum of Modern Art New York, November 22, 1999 – May 1, 2000. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. 1999.

⁴ Erickson, Britta, and Bing Xu. The Art of Xu Bing: Words Without Meaning, Meaning Without Words. Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2001.

⁵ Liau, Shu Juan. Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Blog). “Redefining Art in the China/Avant Garde Exhibition”. February 27, 2012. Accessed 24 June, 2019. https://mondaymuseum.wordpress.com/2012/02/27/1989-china-avant-garde-exhibition/.

⁶ Mao, Zedong. “在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话 Zai yananwenyi zuotanhui shangdejianghua” [Speech at Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art]. Speech, Yan'An, May 1942. Marxist Archive. https://www.marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/marxist.org-chinese-mao-194205.htm.

⁷ The Museum of Modern Art. “The Elaine Dannheisser Projects Series”. Accessed 24 June, 2019. https://www.moma.org/calendar/groups/4.The Museum of Modern Art. “Projects 70: Banners I: Shirin Neshat, Simon Patterson, and Xu Bing”. Accessed 24 June, 2019. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/180.