Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Re/Discovery

Issue: On Re/Discovery

Beatrice Glow is an artist-researcher leveraging interactive multimedia installation and multisensory experiences in service of public history and just futures. Her solo exhibitions include Forts and Flowers, Taipei Contemporary Art Center, Taiwan, 2019, and Aromérica Parfumeur, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile, 2016. Her work has been supported by Yale-NUS College, Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University, and the US Fulbright Scholar Program.

Filed under: archives, installations, technology

¹ Mining the Museum (Cabinetmaking 1820-1860), Fred Wilson

¹ Mining the Museum (Cabinetmaking 1820-1860), Fred Wilson1992, Installation view of at Maryland Historical Society

One of the influences that you’ve picked out

for our conversation is Fred Wilson’s exhibition, Mining the Museum. In the exhibition, Wilson included objects that

were significant to Black and Native American local histories. In doing so,

Wilson challenges the familiar and narrow museological narrative of race and

culture. Given the emphasis on exhibition-making in many of your works, how

does Wilson’s approach inform your practice?

Fred Wilson is a legendary figure in the realm of arts and the curatorial. He transformed the approach to exhibition-making and how artists can work with or within institutions to interpret or intervene dominant narratives. I learned about his work in my first year in art school. I had not been exposed to contemporary art before, so his work was really eye-opening for a young person like me, who always felt excluded from the dominant narrative as a visibly racialised minority growing up in the US.

Mining the Museum is a reference point. Fred Wilson is a Black American artist invited by the Maryland Historical Society to do an exhibition. He wasn't sure how far he could push whilst staying radical and critical of the institution. He asked lots of questions about what's in the museum—what's in their basement, what's on view, and even going through their storage. He presented a remixing of objects in the museum to expose or reveal power dynamics, racialised relations, and issues of inequity. For example, there are the cigar store Indians in the museum, which are wooden figures carved in the form of Native Americans but in an archetypal and caricaturised way that is disrespectful. The figure was—and still is—in many places. They can be seen in front of many tobacco shops. Wilson found a lot of these cigar Indians in the museum collection. He brought them out of the museum’s storage for display, but presented them with their backs turned away from the viewer. It sounds simple, but it is a different way of thinking. Wilson also found silverware in the museum’s collection, because after New York on the Eastern Seaboard, Maryland was one of the largest silver trading ports in the US. Wilson displayed the museum’s silverware collection alongside shackles that were used to enslaved people. He put them in a visual relationship to call attention to this imbalance of power and to what skeletons sits in the closet of an institution. This was back in the 90s, and what he did was quite radical. He opened so much space up for artists, by interrogating and partnering with institutions to tell important stories together—provided there are institutional allies—and to investigate institutional histories.

He has set such a high bar, and is a role model for the kind of work I do. I've had a fellowship at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. That experience was in a way, following in the footsteps of his legacy because I looked at the museum’s archives and collections whilst asking the generous curators, registrars, and knowledge bearers lots of questions about the collections and its holdings. There have been lots of conversations about how we can intervene. I'm going to be doing an exhibition next year at the Baltimore Museum of Art, which is the same city where Wilson did this project. In my project, the conversations have also been about looking at the museum’s collections and asking what sort of perspectives I can bring out with regard to the riches they hold—what kind of interesting dialogues can we create to build bridges with the audience? The work of the artist is not a vanity display of beautiful creations, although aesthetics is an important part of the conversation. A more important overarching theme is: how do institutions, artists, the artworks, and the exhibitions serve the local community and the audience? These are some of the standards that Wilson has generated—he's a leader in the field.

Proportio is a more recent

site-specific group exhibition curated by Axel Vervoordt at Palazzo Fortuny.

Could you tell us more about the significance of this event to your practice? How do you explore exhibition-making as a

medium through research?

I think of exhibition-making as a medium in and of itself. Proportio was an exemplary experience that highlights that. I visited the exhibition at the opening of the Venice Biennale in 2015. It was a group show, curated and installed by Axel Vervoordt’s team. Vervoordt is a renowned collector and interior designer, with an incredible aesthetic eye. Proportio was based inside Palazzo Fortuny, a three-story Venetian palazzo with textiles that were both historical and artisanal—damask and brocade silks were on display since Mariano Fortuny was both an artist himself and a collector of textiles. Every room was different, but it was like a dream space grounded within a historical space with historical works. Vervoordt brought in works that might typically be thought of as “ethnographic objects”, but are actually works of art in and of themselves—or perhaps even sacred objects. He would juxtapose them with contemporary works by artists from the same region. For example, William Kentridge’s drawing from South Africa was displayed alongside historic artisanal work from South Africa. The exhibition was about sacred geometry and proportions—in architecture, music, art, and the visual. It was an endless journey of creating unexpected connections between form, experience, and space. There's no way to describe it. You had to experience it.

On my flight to Venice, I noticed this person who was calling for attention on the airplane. When I got to the top floor of the exhibition, that same person was there again. Time, space, and the experience of my trip happened to converge at the top of this magical art exhibition. He looked at my partner and I and said, “Do we know each other?” There is synchronicity, or conjuration, when you're attuned to metaphors and lived experience within the context of art. Sometimes they become a puzzle that pieces itself together. Those are moments one cannot replicate. Proportio was truly a spectacular exhibition of experiencing the continuum of history, geometry, and the symmetry of our lives. A lot of art is about training your perception, aesthetically, socially, and politically. Proportio was that.

I like old mansions and site-specificity. I grew up near a famous haunted house in America, the Winchester Mystery House. The way the mansion’s owner, Sarah Winchester, came up with the whole design of the space is a form of art. There was a lot of intention put into every corner and detail of the mansion. I've always been enchanted by spaces that brew a sense of mystery, and Proportio is no different. I was also curious about where Sarah Winchester’s wealth came from. It turns out she inherited the Winchester Repeating Rifle Company’s blood money, and built the house to evade ghosts. This Winchester story encapsulates a century of US settler history, and I've always been fascinated, horrified, and attracted to stories of contradictions. I am planning new projects with historic mansions right now.

There is synchronicity, or conjuration, when you're attuned to metaphors and lived experience within the context of art. Sometimes they become a puzzle that pieces itself together.

² The Smoking Room, Beatrice Glow

2021

2021

To continue on this theme of spiritual and mystical

experiences, Nicolás Dumit Estevez Raful committed himself to the nocturnal adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament in his Nocturnes performance. During the seven days spent in the cloisters, he vowed to refrain

from any form of communication with the outside world. In what aspect, if any,

does this work helps you to think about introspection and the act of healing?

Nicolás Dumit Estevez Raful Espejo was, and still is, a mentor of mine. When he emerged from this performance, I was there to witness it. Nicolás truly blurs and treads that in-between, liminal space between art and life. When he emerged from the convent, we did this pilgrimage walk around the neighborhood with him, and ended up at an art space where he gave a talk. It was his first time speaking after seven days of silence, and he told us about his experience. There is definitely an aspect of healing, spirituality, meditation, and transcendence, among many other ways to interpret what he did. What I took away from that was that he was taking on the burden of the nuns so that they could rest without worrying about holding the space during night duty. When he shared what he had experienced in the convent during a performance, I thought to myself, “Oh, he's a punk monk.” He's not following the ways of organised religions that stipulates how monks should behave. Instead, he created his own rituals and ways of taking on suffering by sacrificing for, and empathizing with, others. He wasn't doing it for the audience per se, although there was that component. That introspective journey he undertook was just for the nuns in the convent alone, and I admire that so much. He went on to study at the Union Theological Seminary, which was a truly radical journey for an artist. This performance was where he really marked me.

He has continued to guide me in my journey, though our works are quite different now. I think we can always connect on the point of honouring that interior space, empathy for others, caring and healing. That is always a very precious way of being—in community and with other people that we may not know, but holding them close to our hearts nonetheless. He always models that for me, as he generously did that for me as a young person. There have been moments during which I needed guidance, especially during the pandemic. He recently invited me to do a very unconventional residency with him next summer. During the residency, I will be able to have consultations with him and develop work. At the same time, he’s also asking me to pause for a little in my life and be more introspective. The residency doesn't ask me to produce anything per se. It is set up to support my process, which is what a residency should be. Today with the professionalisation of the arts and the need to meet the requirements of funders, residencies often demand artists to produce something. Nicolás’ way of doing things is inherently anti-capitalistic. It is focused on well-being, which is a luxury of mentorship. I cherish his friendship. He's an impactful figure. Can I make a plug for him at this point? He is a fascinating, truly eccentric, and lovely person, and Nocturnes is a long-term conversation.

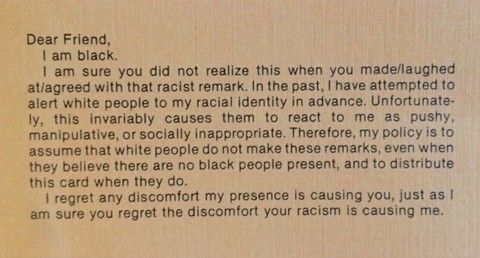

³ My Calling (Card) #1, Adrian Piper 1986

³ My Calling (Card) #1, Adrian Piper 1986

On this aspect of relationships with others, Adrian Piper’s My Calling (Card) provides a new

approach to mediating the process of calling out racism and hypocrisy. It can

be difficult to gauge the extent of discomfort that the artwork is meant to

create for its viewers. How has Piper’s approach influenced how you think about

reception and viewer engagement?

I learned about Adrian Piper's work as a student. At the time. I was feeling quite vulnerable—as a young person, a racialized minority, and a small-sized woman in New York City. Adrian Piper was brave to be doing such works in the 70s and 80s, pointing out uncomfortable things. She has a very famous essay titled Passing as White, Passing as Black, where she talks about the in-betweenness of her physical appearance. When she's with predominantly white people, they often assume that she is white, and sometimes saying things that are very offensive to her and her racial identity. When she was growing up in Harlem, NYC, kids would call her “White Girl” or say she's not black enough to be Black. She could either be very angry because she was constantly othered, or she could use that specific insight to call out the hypocrisy. She saw the unique space that she occupied and decided to leverage that to help us see our issues. I admire her so much for all that she has done, which was quite unsafe. She wasn't doing this for pleasure, but out of pain. She didn’t have the luxury of choosing to do nothing, which makes her work really impactful. My Calling (Card) was my first introduction to her practice. It's aggressive because she wasn't going to sit down and take it.

I did several projects as a younger person in which I would confront people in different ways. When I was going to school at New York University, they had just acquired this building. They let the artists go in to do an exhibition. I did a performance where I decided to be a bouncer and set my own criteria for profiling people. I didn't let anyone who was over 21 years old look in, and made white people wait in line. It was arbitrary. I think that was quite bold to do for a young person, and a lot of that was inspired by Adrian. She also informed my work later in Peru when I was thinking about Asian and Latin American history, culture, and migration patterns, and what it means to think about identity politics and racialised and gendered experiences, and how one can find agency within disempowering situations.

I also find Wangechi Mutu’s work inspiring, especially the way she combines and remixes images from medical education books, fashion magazines, and anthropology to talk about the objectification of women of color. I once attended a talk of hers, and the way she tells her stories was so captivating. I asked her, “How do you do so much research whilst finding a way to create a work of art?” I remember that she said with a very wise voice, “You just have to let it marinate.” That's stuck with me for years. Your stew might take a long time to make, and that's okay.

⁴ Rhunhattan Tearoom, Beatrice Glow

2015

⁵ Rhunhattan Tearoom, Beatrice Glow

2015

2015

⁵ Rhunhattan Tearoom, Beatrice Glow

2015

Many of your recent works are created using VR sculpting, a

tool that can create a very visceral viewing experience. What piqued your

interest in VR, and what expressive potential do you see in this medium for

your practice?

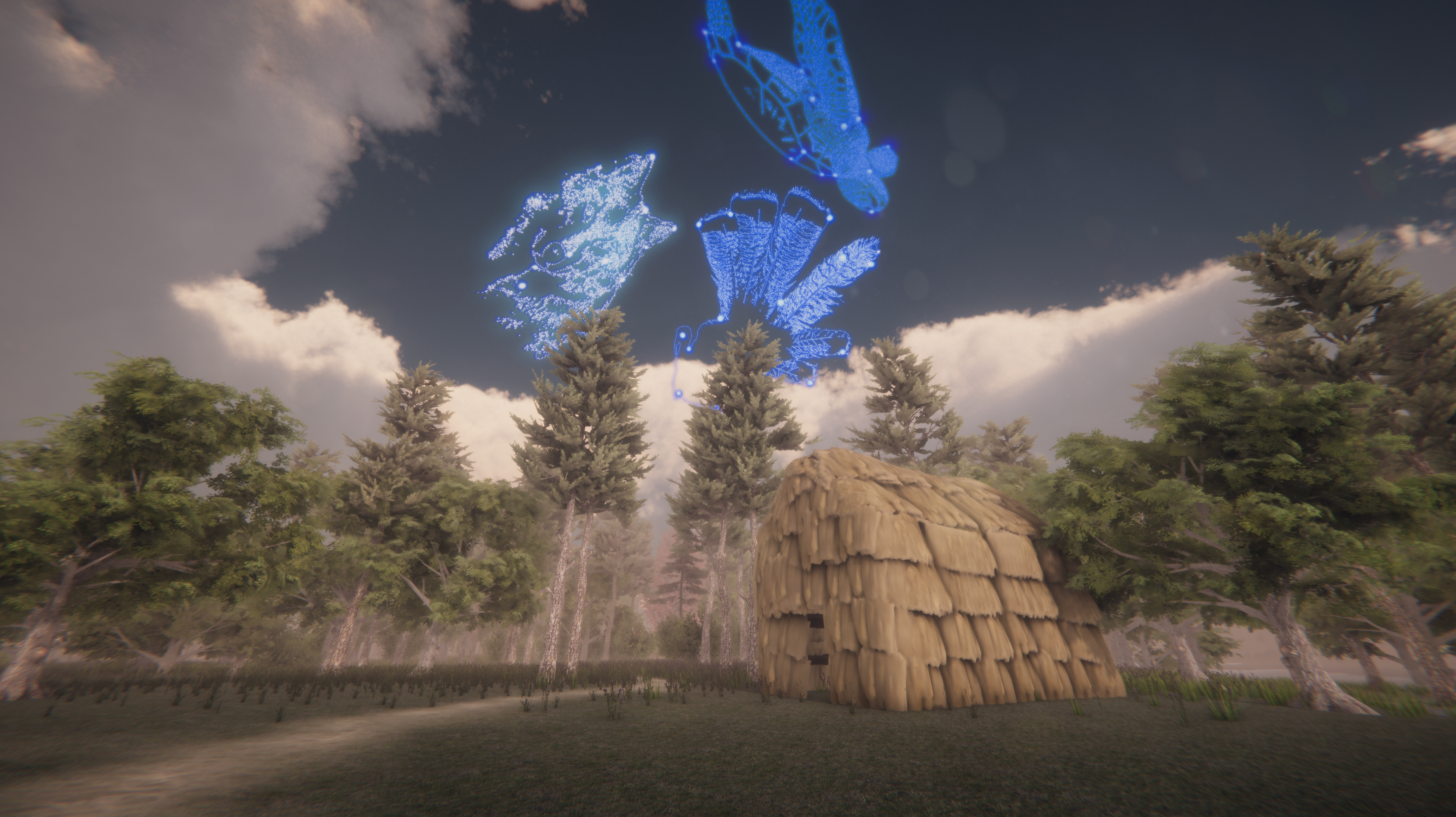

My partner, Alexandre Girardeau, was a graduate student in Montreal. Between 2014 to 2015. he was working on several projects about consciousness, ego death, and virtual reality. At that point, VR was a relatively new medium, and Palmer Luckey had just created this new headset, Oculus Rift, that became available for developers and subsequently, consumers. At that moment, there was also a lot of reckoning in New York about how to tell important stories around Indigenous histories and how to be in allyship with the original peoples of the land, the Lenape/Lunaapeew/Lunaape, in this process.

As the 2016-17 Artist-in-Residence at the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University, we started to think about digitally reconstructing the many-layered stories of New York from Manhattan, and how we could invite cultural bearers to be a part of that experience, allowing people to hear directly from them, to amplify their work. At that moment, VR was what we were capable of doing. We researched the environment where the university was located, and recreated what might be palpable based on topographic and ecological evidence. The whole point of the project was to inspire curiosity in people to do their own research. We wanted to inspire others to use this medium for their own research. We were very privileged to start the process of building relationships and kinship with Indigenous culture bearers, including Chief Vincent Mann—the chief of the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, Turtle Clan, as well as Lunaapeew culture bearers George Stonefish and Brent Stonefish. They were really open with me throughout the process. We did volumetric scans of them telling stories and messages for future generations, and brought these experiences to audiences through VR. Chief Vincent Mann told me that he wants his future descendants to be able to meet their ancestors in VR. It's also a way for them to tell stories without having to speak to many people. People can meet them—almost as a spiritual presence— while wearing headsets and walking through the past, present, and possible futures of Lower Manhattan in this digital environment.

Another point of motivation for this project was this constant misconception that indigeneity is not compatible with modernity. We wanted to challenge or play with those perceptions. What if we could tell these ancient creation stories through a medium that is, at this point, considered new and hip? Some of the elders we consulted with were very interested in us developing this and transferring the project to Indigenous youth in their communities, so they can take it on, and tell these stories themselves. In hindsight, that was quite idealistic of us as doing that work required a lot more time and commitment. Nonetheless, those were very important thought processes that we went through. I still have hope that one day, the project could be passed on. It got me thinking about what it means to work as a committed ally and what roles can artists and/or allies assume to share the burden while those whom we want to support have to deal with more urgent community issues.

I think very few VR experiences are convincing. However, Notes on Blindness was well suited for the medium. Notes on Blindness was so thoughtful. The audience is in darkness for most of the time, while listening to a man narrating what he sees, senses, hears, and as well as his experience of gradually losing his eyesight. Everything is so pared down that your attention is fixated on tiny visual perceptions and stimulations while you're wearing the headset. I literally took off the headset crying because it was so beautiful. There was so much poetry within the storytelling process. It was one of the earliest VR projects and one of the best experiences for me.

The whole point of the project was to inspire curiosity in people to do their own research. We wanted to inspire others to use this medium for their own research.

⁶ MannahattaVR, Beatrice Glow

2016- 2018

⁷ MannahattaVR, Beatrice Glow

2016- 2018

2016- 2018

⁷ MannahattaVR, Beatrice Glow

2016- 2018

2013, Installation view at Musée d'Art Contemporain de Montréal

Your works, such as Smoke

Trails, also challenge the authenticity of history. Has Laurent Grasso’s

work—his exploration of space and temporality, and the representation of

power—informed your practice, particularly in the way you examine the layers of

reality and possible worlds?

My first encounter with Grasso’s work was also very transformative. It goes back to that earlier conversation we were having on Proportio and the Winchester Mystery House. It's a phenomenological experience to encounter his work. Grasso’s enormous installation at the Montreal Contemporary Art Museum was a highly produced institutional show, but he really challenged the way in which one experiences art. It is like going through a labyrinth, and suddenly there's a window on this wall next to you. You can see a glimmer of something inside, whether it's neon lights, or a section of a painting. I like when the work activates the space, and activates the viewer to engage with the story and narrative, and that often happens in Grasso’s films, installations, and paintings. It was deeply inspiring, and I always think about how I can create an immersive experience that suspends a certain level of reality.

For example, Aromérica Parfumeur was an intervention I did in a shopping mall. When visitors walked into the space, people may have thought that they were entering a perfume boutique. Instead, they came face to face with counter-histories. It's about balancing what is not told, and the act of bringing it into our memory space. It is a process of truth telling and reconciliation through art. I have used this process to deal with difficult histories, such as genocide, which I approach in a more organised way through my work with the Banda Islands. In art, it is important to maintain a tone of service—we are telling a fuller story. I'm not trying to skew or rewrite history, but to tell—to a fuller extent—the histories that are omitted from public education, popular narratives, urban legends, and from the stories we tell ourselves. I try to make the real more real, perhaps. The virtual experience itself doesn't matter in the end. It's about hearing and trying to hear. The virtual is full of potential. It is the perfect cousin of conceptual art or performative instructions. They all play the same game, and it’s about using language and medium to find out what's possible. For every generation, it's different. As artists, many of us are just fascinated by ideas and theories and the final medium is sometimes much less relevant.

In art, it is important to maintain a tone of service—we are telling a fuller story. I'm not trying to skew or rewrite history, but to tell—to a fuller extent—the histories that are omitted from public education, popular narratives, urban legends, and from the stories we tell ourselves.

When imagining a just future, every element that you choose

to include come with intentionality and contributes to the broader narrative.

Has your world-building process been influenced by theatrical elements and

forms?

A hundred percent. It's not really about the medium, but what you're communicating. I grew up with performance and dance. Between the ages of seven to fifteen, I was on stage all the time performing—dance, theater, and traditional folk arts. When I was living in Peru, I studied with the Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani. Yuyachkani is a Quechua word for “I am remembering, I am thinking”. They were an activist theatre group that was predominantly started by young people studying theatre at the university in Lima. They realized that the education they received was derived from Western or European theatrical traditions, and what they performed did not speak to the audience that they wanted to reach, which were mostly indigenous and marginalized communities. They decided to unlearn what they received from their formal educational experience as well as preconceived notions of high art versus folk art by travelling and living within various Indigenous communities throughout Peru to learn about their art forms—dance, music, performance, and aesthetics. They created a form of theatre-making methodology that is really their own. It incorporates all these art forms and embraces multiculturality. This collective of legendary teachers and theatre artists have been working together for about forty years.

Their way of solidarity, ethics, how they communicate, and how they activate a space has really inspired me. Their performance moves through where the audience is sitting—working with the senses of smell and taste, with movement and music—to tell an important story that is not medium-specific. That is how I work too. In that sense, my storytelling is definitely influenced by artists who go above and beyond to create a vocabulary that allows them to impact, influence, and dialogue with their audience.

⁹ Smoke Trails, Beatrice Glow

2021

¹⁰ Smoke Trails, Beatrice Glow

2021, Installation View at Collaborative Survival, 601Artspace, New York

2021

¹⁰ Smoke Trails, Beatrice Glow

2021, Installation View at Collaborative Survival, 601Artspace, New York

Many

themes and ideas that you explore in your work require audiences to unlearn

certain things before looking at them again through a fresh perspective,

thereby expanding reality as we see it. Do you see your work as research, where

you attempt to rediscover and push back against dominant narratives? How does

that help us imagine a just future?

I try to challenge the dominant narrative in circulation, which is often constructed by people in power. We must never underestimate the power of a story. The stories that your parents tell you as a kid will shape you. They will either empower you to believe that you can do certain things, or break you down into thinking that you're lesser than. We are fed these stories as children, and they continue to impact us as we grow and enter society. They shape our behaviour—depending on our gender, race, culture, identity, and class.

What I'm trying to do is to make this work accessible. I use art and research as methods to co-labour with people across different academic fields, and to work in collaboration or consultation with people who based within certain communities. I want to ask how we can rethink the hierarchy that we perceive to be the norm—how can we exist together in a more horizontal space? In practice, it's very difficult. I do that through work that is rooted in cultural organizing. Art can be an applied research space for public education and public engagement.

What I'm trying to do is to make this work accessible. I use art and research as methods to co-labour with people across different academic fields, and to work in collaboration or consultation with people who based within certain communities.

¹¹ Aromérica Parfumeur, Beatrice Glow

2016, Installation View at Sala de Arte del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile en Mall Plaza Vespucio

¹² Aromérica Parfumeur, Beatrice Glow

2016, Installation View at Sala de Arte del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile en Mall Plaza Vespucio

2016, Installation View at Sala de Arte del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile en Mall Plaza Vespucio

¹² Aromérica Parfumeur, Beatrice Glow

2016, Installation View at Sala de Arte del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Chile en Mall Plaza Vespucio