Known for his sculptures in rattan, Sopheap Pich’s works have been exhibited in galleries and museums all around the world. We sat down with conservator Bettina Schleier, who worked on Sopheap Pich’s Delta whilst it was on display at Art Porters Gallery. Owing to the sculpture’s age, some of its original iron wires had rusted or corroded. Bettina tells us more about the process of working on this project, and what her work as a conservator entails.

Dipl. Rest. Bettina Schleier was born in Austria and went to school for Art and Design there. After working in arts and craft she studied Art Conservation in Erfurt, Germany. She has worked as conservator for more than 10 years in countries such as Germany, Austria, Taiwan, Ghana and Singapore. Her passion lies in building bridges in heritage conservation and working in many countries around the world.

Dipl. Rest. Bettina Schleier was born in Austria and went to school for Art and Design there. After working in arts and craft she studied Art Conservation in Erfurt, Germany. She has worked as conservator for more than 10 years in countries such as Germany, Austria, Taiwan, Ghana and Singapore. Her passion lies in building bridges in heritage conservation and working in many countries around the world.

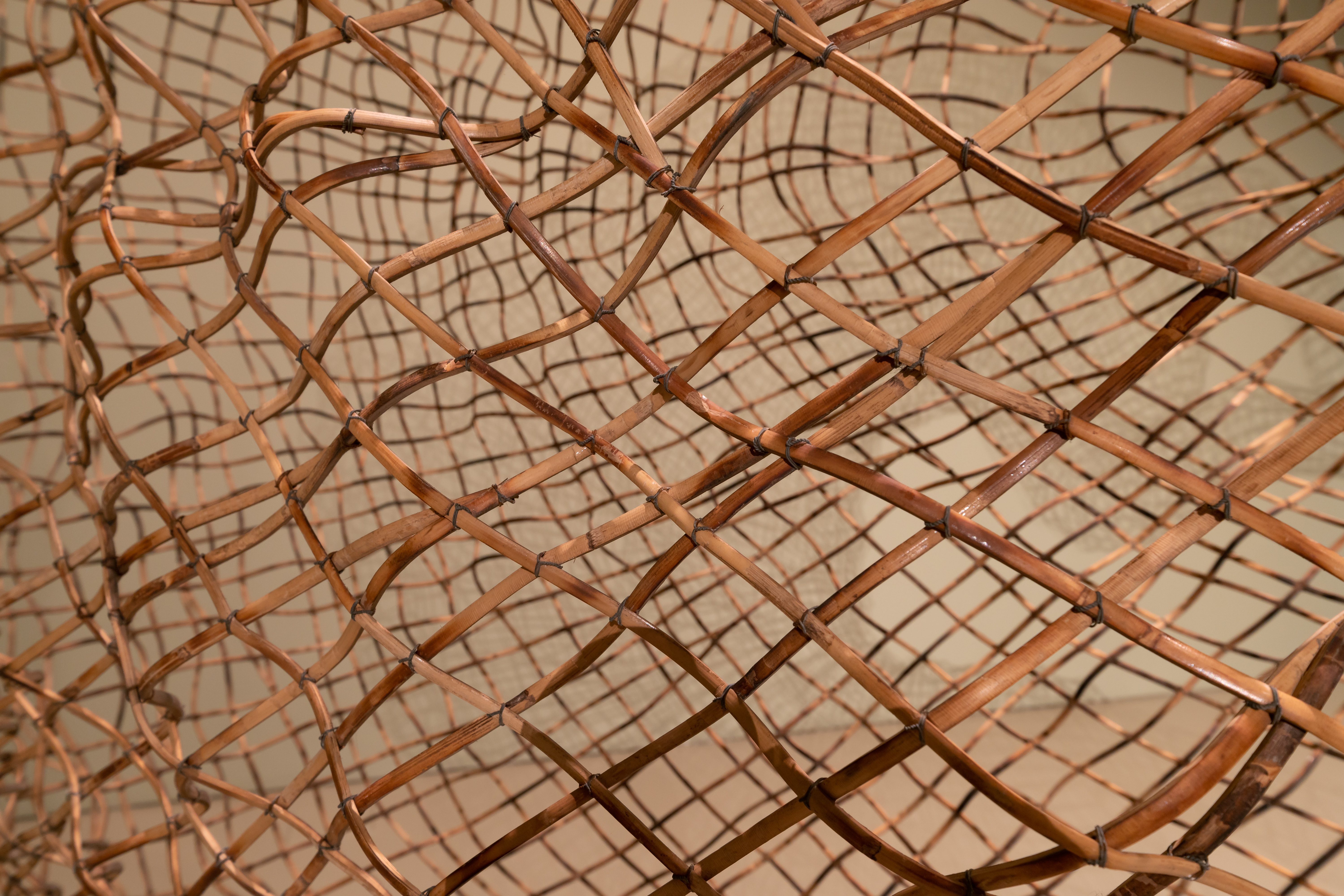

¹ Delta, Sopheap Pich

2007, Trees of Life – Knowledge in Material Installation View at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore

Credit: NTU CCA Singapore and The MaGMA Collection

2007, Trees of Life – Knowledge in Material Installation View at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore

Credit: NTU CCA Singapore and The MaGMA Collection

THE MATERIALITY OF THE SCULPTURE

Bettina Schleier (BS): When Delta went on loan to the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art for an exhibition titled Trees of Life – Knowledge in Material, it was clear that the artwork needed some conservation treatment. The team reached out to a colleague of mine, Hanna Szczepanowska , who works at the Heritage Conservation Centre as a conservation scientist. She pointed the team in my direction, and that was how I came to work on the sculpture.

The sculpture is made of rattan, and held together by iron wires. Over time, these wires began to rust and this corrosion was affecting the rattan structure itself. The sculpture is also constantly in flux. It was being moved around quite a bit, and every time someone touches it or even when a breeze blows past it, it moves. When conserving this sculpture, I kept all of this in mind. I considered treating the sculpture with a stable agent, such as resin, but that wouldn’t have prevented the work from cracking. Initially, Sopheap recommended painting the sculpture over with varnish. As a conservator, it’s important that I preserve the state and the material of the artwork as it is. After assessing the artwork, it became clear to me that coating the sculpture would not be ideal and even could cause some damage in future.

In order to develop a comprehensive conservation approach, I needed to know everything about the artwork. I needed to know how the rattan was harvested and prepared, so I asked Sopheap about this in a short interview. With Delta, he cooked and boiled the rattan in diesel oil before bending it into shape. This sort of information was important for me, because now I knew that not only was I working with rattan and iron, I was also working with oil in the sculpture. The oil will degrade over time, and the byproducts of this degradation would exacerbate the corrosion of the metal wires. The rattan structure itself, though, is in very good shape. It is a tropical plant, and it is made for this climate. Rattan also has this natural, glassy sheen to it because of siliceous compounds that exist in the plant’s epidermal layer.

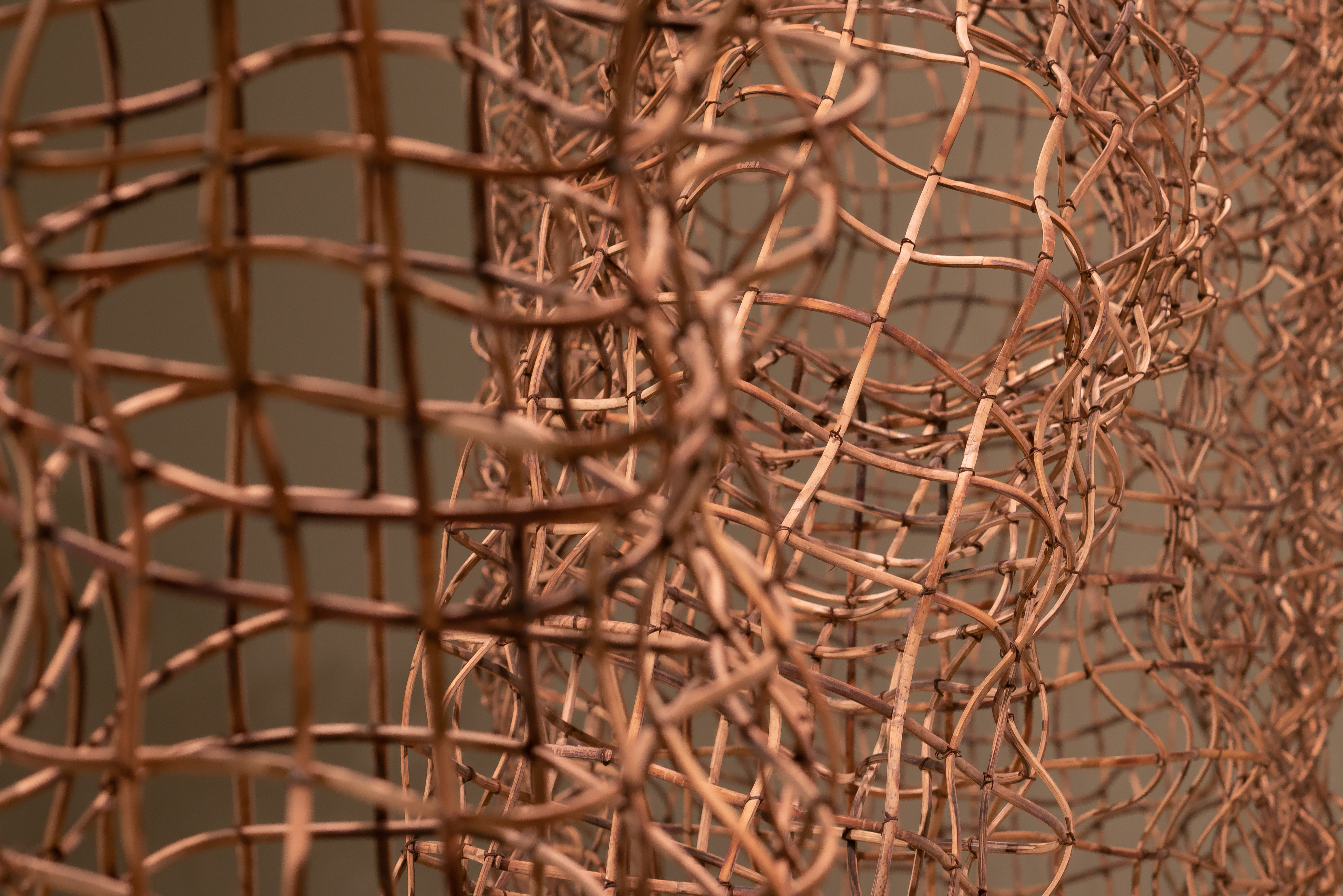

² Delta, Sopheap Pich

2007, Detail

Credit: NTU CCA Singapore and The MaGMA Collection

2007, Detail

Credit: NTU CCA Singapore and The MaGMA Collection

BALANCING CONSERVATIONAL CHOICES

BS: For conservators, it can be tricky negotiating such decisions with artists. After all, it is the artist’s work and they know their own artwork best. I see the artwork, primarily, as a material object — I see the rattan, the iron joints, and the environment it interacts with. What the object or the artwork means is a secondary concern.

I wrote to and met with Sopheap a couple of times, asking him what the sculpture meant and how important the iron joints were to the artwork and its message. Through our conversations, it became clear that the rattan was the focus of the artwork, and not the iron wires. He sees the wires as replaceable, and so I asked Sopheap if the iron wires could be swapped out for a different material. Given Singapore’s tropical and humid climate, replacing the old iron wires with new iron wires would not prevent future corrosion. I did some research, and proposed a couple of material options — namely aluminium, titanium, steel and copper. Eventually, we settled on titanium. Titanium comes in different grades, with grade 1 being more flexible, and grade 5 being used in medical procedures. Sopheap himself has a background in medicine, so I thought the use of titanium would be fitting.

This was one of Sopheap’s earlier works, and during his artist talk, he spoke about his experience of being an emerging artist. When he was first starting out, nobody wanted to see his artworks. Having worked on Delta, I see this desperation in the artwork and I realise that spirit as being integral to the artwork. If I had covered the structure with a glossy surface, I would have negated his artwork completely.

Sopheap was so supportive throughout the process. Both him and his assistant have been working with rattan for years. As a result, they’ve developed a special technique for handling the material, and he offered to show me the ropes. He even brought the tools for me, and gave me tips for avoiding blisters on my hands too.

³ Delta, Sopheap Pich

2007, Pre-Conservation Detail

Credit: Bettina Schleier

2007, Pre-Conservation Detail

Credit: Bettina Schleier

CONSERVATION AS A RESPONSIBILITY

BS: I really appreciate the work Art Porters Gallery does in helping young Singapore-based artists. Conserving the sculpture at the gallery was a great experience, because I got to have conversations with gallery visitors throughout the process. I was able to tell visitors about the importance of conservation, and to get them thinking about the materiality of the artwork.

When people think about purchasing an artwork, collectors often think about a work’s attractiveness. However, these works need to be responsibly maintained for the long term. These works will be important to the study of art history — they will show future generations who we were, and what was important to us.

As a conservator, I am aware of the fact that every intervention and every material I incorporate will add yet another factor to future processes of decay. As a conservator, I can’t turn back the clock — I’ll never be a 16th-century artist and so, I can’t think like a 16th-century artist either. Instead of trying to step back into the shoes of the artist, I’m interested in drawing out the history that lies within an artwork. Of course if an artwork is no longer clear or visible, some retouching is necessary. However, it is about doing as little as possible so as to preserve the artwork’s history.

POST-CONSERVATION THOUGHTS

BS: This project was very special for me. I’m used to working with heritage boards, museums, and private clients; and usually I work on conserving the artwork within my atelier. In comparison to that, I got to work on Delta inside Art Porters Gallery itself, and was able to get in touch with the artist as well. The vast majority of the artworks I conserve are not contemporary, so I’m often not able to consult with the artist on their work. This experience got me thinking about what would be meaningful for the artist.

I also made sure that a full report was done, detailing the conservation work I did on Delta. This provides future conservators with a reference point, and will explain the conservational choices that were made. Conservators keep track of their work and write detailed reports that, hopefully, will be of use in the future.