For the first few posts here at Object Lessons Space, we'll be speaking to the artists who were a part of The Deepest Blue.

We begin this series with a heartfelt chat with Chloë Manasseh. Chloë is a visual artist who works between Singapore and London. Her practice has a focus on painting, but also includes video, installation and performance. Recently, she was involved in solo shows at NPE Art Residency and Gallery (Singapore), The Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair (London), and The Affordable Art Fair (Singapore). She holds a Master’s from The Slade School of Fine Art.

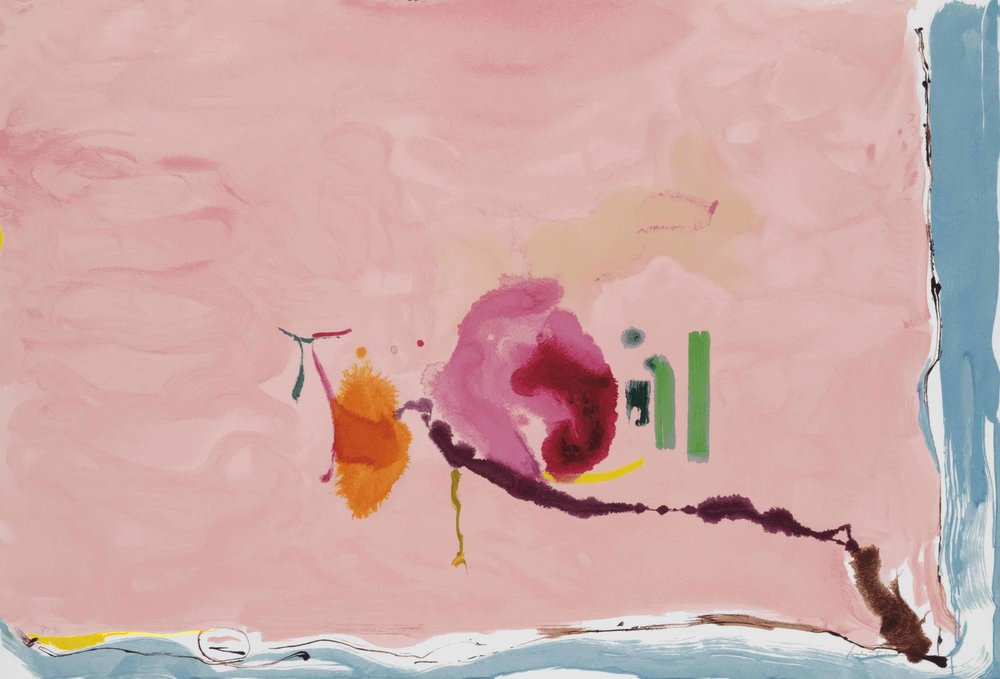

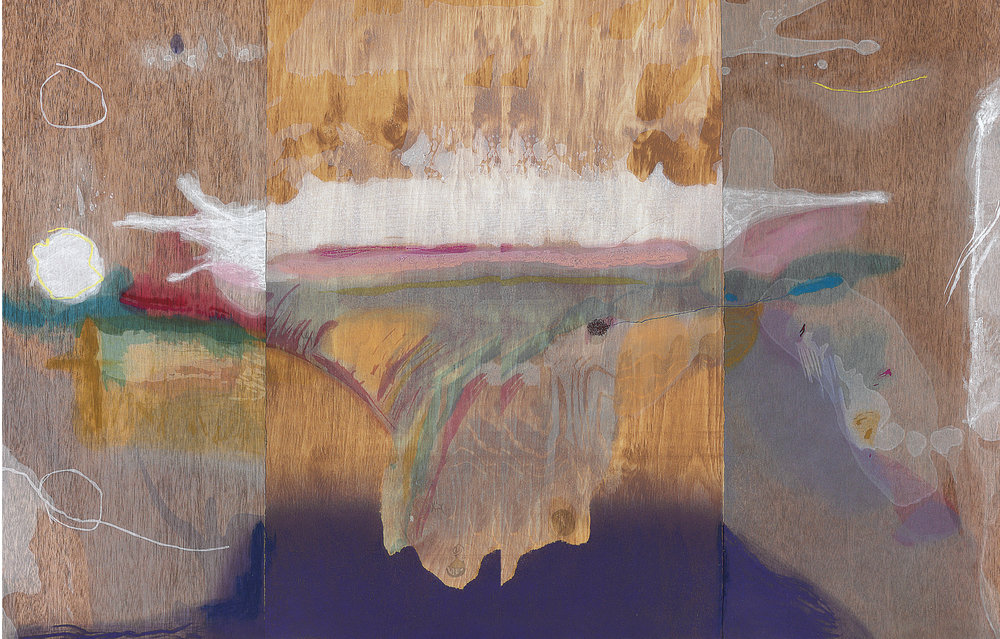

She was particularly drawn to the works of Helen Frankenthaler, especially Flirt (1995) and Madame Butterfly (2000). Here, we chat more about how Frankenthaler has been an influence on her artistic practice, and the unchartered territory she sees herself moving towards in the next couple of months.

We begin this series with a heartfelt chat with Chloë Manasseh. Chloë is a visual artist who works between Singapore and London. Her practice has a focus on painting, but also includes video, installation and performance. Recently, she was involved in solo shows at NPE Art Residency and Gallery (Singapore), The Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair (London), and The Affordable Art Fair (Singapore). She holds a Master’s from The Slade School of Fine Art.

She was particularly drawn to the works of Helen Frankenthaler, especially Flirt (1995) and Madame Butterfly (2000). Here, we chat more about how Frankenthaler has been an influence on her artistic practice, and the unchartered territory she sees herself moving towards in the next couple of months.

¹ Helen Frankenthaler, Flirt

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, 1995

² Helen Frankenthaler, Madame Butterfly

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, 2000

³ Helen Frankenthaler, Mountains and Sea

National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1952

It'd be great to talk about the piece you've just created for the exhibition, but I understand that you've been interested in Frankenthaler for awhile now, and it wasn't just something you tapped into for this particular work. So I'd like to start by talking about how that has resulted in the piece as you've conceptualised and created it, and if any other artistic influences have been feeding into where your practice is going and where you see things moving for yourself.

Yeah, when Racy (the co-curator for The Deepest Blue) asked, “Can you think of any female painters that look into mental health?”, Frankenthaler just popped into my head. I had no context for the question or anything like that.

When I was at Brighton doing my bachelors about nine years ago, I came across her work but hadn't done any research and completely coincidentally, actually, started doing the stain technique. Only because I was completely broke at the time, you know, being a student, I probably spent my money on going out. I didn't have enough money to buy ground, to buy gesso, so one of the tutors asked me to consider watering down glue. I was just lazy, so I did it just once thinking it would be enough - but it wasn't, and everything ended up staining through. But I really enjoyed the technique, and my tutors began introducing me to Frankenthaler.

I really engaged with her work, primarily through her sense of colour as colour's really key in my work as well. But also, I really liked how she engaged with space. It is brave, in a way, to just allow colour to sit in a space, and to allow it to just exist within a plane. A lot of her work was also left to chance, where she would just stain and see what would happened. Especially in works such as Mountains and Sea (1952), she engaged with the shapes that were present and created her own outlines.

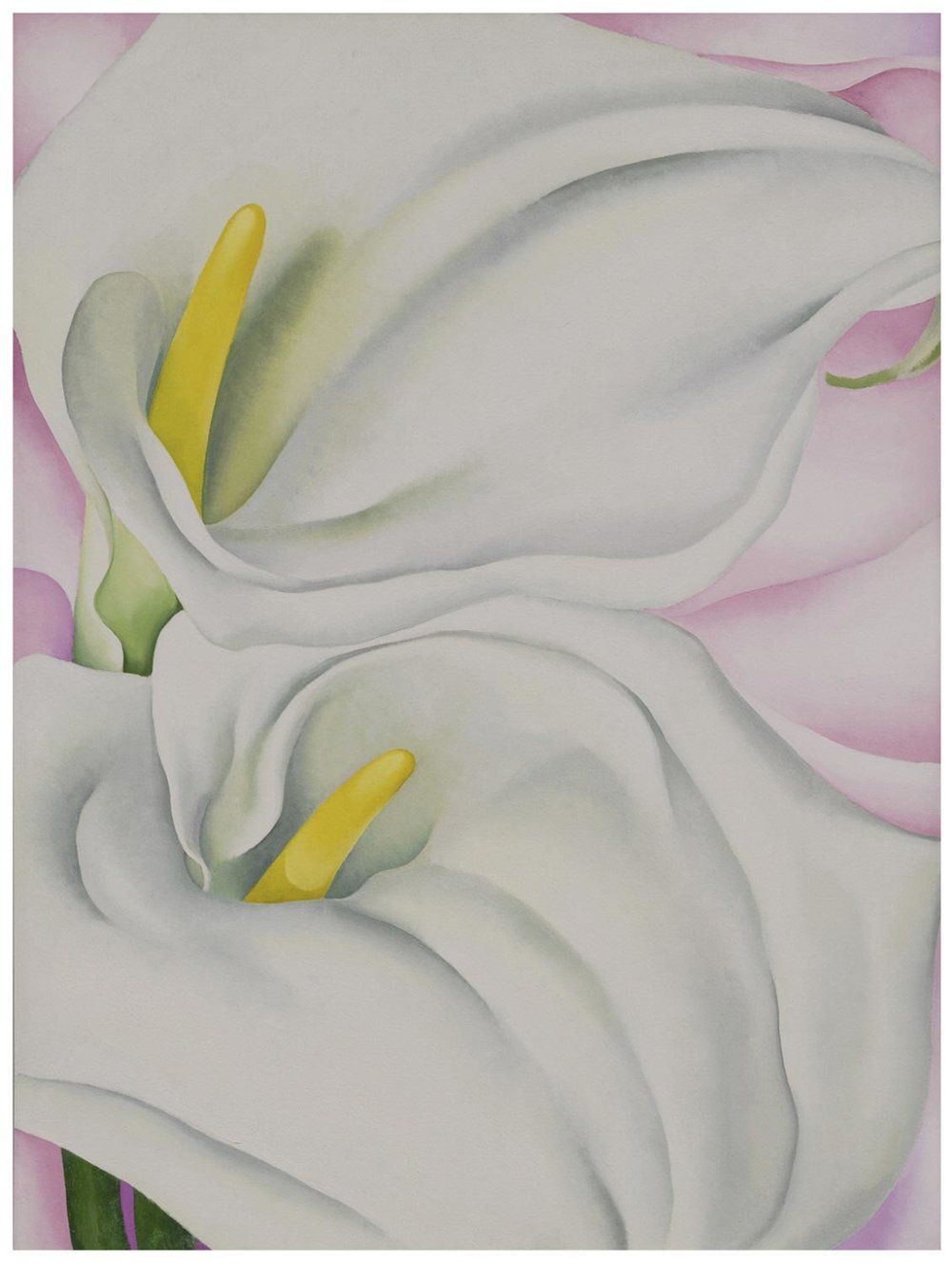

⁴ Georgia O'Keeffe, Two Calla Lilies on Pink

Philadephia Museum of Art, 1928

Yeah, when we look at the works she did using the soak-stain technique, it was very much based on chance — how the colours would interact with each other, and how she could get things to flow along the canvas. It almost seems like she had a vague idea of where she wanted it to go, but how it eventually looked like could differ greatly from the image she had in her mind. This really pulls back to what the exhibition is about as well.

At the same time, she's often tried to refuse labels that people have assigned to her work. She's been hailed as the antithesis to Jackson Pollock's work, and a feminist artist — whatever else that term must have come with during her time. She brought a new perspective to the table where the work should be allowed to speak for itself.

Thinking about the time [Frankenthaler] was working as an artist, even if you compare her experiences to other female artists such as Georgia O'Keeffe, art critics would immediately associate their works with the feminine. Georgia O'Keeffe also often denied that any of her work had any feminine ideas or notions behind it, yet that's been a prevailing sentiment throughout history. But if you can't take the artist at her word, then what can you do? It's a shame that she felt she had to deny the femininity in her work, because I do think there are feminine traits within certain paintings. For example, Flirt, is an incredibly feminine painting, in my view as well. But I understand her reluctance to associate herself with the word, especially at the time.

Certain words that were used to describe works such as Flirt that seemed almost reductive, although they were objectively accurate. This included terms such as “soft colours" and “pastels". Yet viewing these paintings, it's clear that her use of colours extends beyond being mere “soft colours" and “pastels".

I agree. There is a boldness and braveness about her work — it's unapologetic, which I think is really important. She also stated that she wanted to make "beautiful work", which is also another word that's so inky — even now, it's incredibly taboo. You don't want to make beautiful work. When I was at art school, when people said your work was beautiful, it wasn't said as a compliment. They'd say, “Chloë, why is it so beautiful? Man it up a bit, edge it up a bit!" But it's almost more confronting to make something that's so appealing, something that makes people wonder if they're allowed to like it.

There also isn't a set form of rules with which to approach her works. The usual vocabulary that we use to describe art just doesn't work when we are confronted with Frankenthaler's works.

Coming back to what you mentioned about painting remaining a very male-dominated industry, how has your experience been like working within this landscape? What sort of things have people said about your work that, you feel, diminishes what you want to convey or get across; and how has criticism missed the mark with interpreting your intentions?

I think something that I've had to be quite strict with myself is realising that I'll never be able to control what comes across in works — be it what I'm thinking or what my thoughts are behind the works. I'm never going to align fully, even if they've read the artwork descriptions, with what other people perceive. And I think that's really important.

What I value most within my own work is that, or I'm hoping at least, it has a space in it to allow people to assign their own imaginative values to it.

Whether it is for someone purely decorative, which is for me what I personally find the most challenging — when someone reduces it purely to a decoration. It happens often with selling art, and the selling artist, which isn't something I'm dismissing because it's huge. But, you really have to detach yourself sometimes, from someone who just wants to decorate their wall. At the same time, it's incredibly humbling that someone wants to live with what you've made. But sometimes, they're seeing it as a decorative picture. Yet that shouldn't necessarily be a negative. At the end of the day, I know that the work I create is visually attractive to some people, and beautiful, for want of a better word.

It's really about detachment. Because I can have all of this meaning laden onto a work, but what does it actually matter, and who am I doing it for?

Do you see the work taking on a separate dimension of meaning, depending on which home it goes it, who ends up looking at it, purchasing it, or viewing it? How do you envision the viewer's experience as adding a dimension, if any, to your work?

I think it inevitably changes if you're living with the work as compared to seeing it in a gallery context, or in the context of other works as well.

I'm young enough, and at a stage in my career where I've still been very involved in the selling process of my works. I know everyone who's bought my work personally, or I've gotten to know them throughout the selling process. They've all engaged with the work for different reasons, but when they're living with the work it does change. For some, it's in a big, expansive room and it's the only artwork they own — which is really special. But then, a young collector bought my work a few years ago, and I helped install it in her flat. And it was floor to ceiling. The whole flat was inundated in art because she was just so passionate, and art was what she spent her money on. I thought that was really special too, because she was just a year older than me as well.

But obviously once it's in the context of a gallery, it does add a layer. People immediately assign more to a work when it's seen in a gallery or in a professional context, because you're expected to. There's an expectation behind the show, and an expectation behind the viewing.

The other work you were really struck by was Madame Butterfly, a woodcut. Which is interesting, because people know Frankenthaler's soak-stain works best, but have rarely gone beyond that into exploring how she experimented with other techniques throughout her career. What was it about the piece that spoke to you, and why did you choose it?

There are a few reasons. Partly because it was a triptych, it expanded the landscape across multiple planes, almost creating a borderless landscape. Inherently, every landscape we look at is bordered — whether we view it through our vision, through a photograph, or through the cultural contexts we assign to places and things. This means that we've already got an idea in our mind of what we're going to look at before we look at it.

I think what's interesting about this piece is the way it expands across different planes, and it feels like it could be ongoing. Like with all of her works, they are not necessarily contained within the borders of the canvas or the wood. They feel like they could just continue and be expansive. For me, it was really similar in sensibility to her soak-stain work. But woodcut is an incredibly precise art form. Having read up on the piece, she used an incredibly precise technique and looked at Japanese woodcutters. She created something that felt so raw and unbound, in comparison to many other woodcuts I'm familiar with.

⁵ Henri Matisse, The Snail

Tate, 1953

She transformed something that would have otherwise have defined lines and clean strokes into something that looked similar to her soak-stain works. But when you realise it's on wood, and it's made with woodcuts, it's clear that she did something really different with that technique.

You mentioned that it was her use of colours and her sense of space that really drew you in. Yet, there are so many other artists that have used colour and space in collages and cut outs. Why Frankenthaler's work, in terms of colour and space, as compared to someone who's used it in a collage format, like Matisse?

Actually I find Matisse also hugely influential, and I've looked at a lot of different types of artworks.One of the best pieces of advice I'd ever received from a tutor was to finish my work. This was considering he was looking at a whole studio full of finished paintings, so it took me a very long time to figure out what he meant. He said I'd get what he meant eventually, and I did. He meant that you have to show you care. When you're a student, or at least when I was doing my bachelor's, you're being so prolific and you're doing so much work. The care to finish a painting properly and to engage with it to its full potential can get lost because you want to try out all your ideas.

It's just something that's always kept with me.

As my styles have evolved and have shifted into different narratives and figurations, as it were, that is a piece of advice that has always stuck with me — like how will the work finish? Even if its a plain canvas, what does that mean to me, and why is that finished?

That's what I enjoy about Frankenthaler. Her works weren't completely, as you said, random. They feel a little curated. There's a point you tell yourself to stop.

⁶ Peter Doig, Architect's Home in the Ravine

Saatchi Gallery, 1991

There's a sense of control, which is interesting in terms of managing the tension between holding back and letting paints seep through. Coming back to how you understand her work, and how she was the first artist that you felt you didn't have to recreate. What was it about her work that allowed that, or were you just at a point in your career where that shift was timely?

This was actually when I was incredibly young and just starting, I wasn't even sure if this would be my career. This was during my first year in Brighton, right after foundation, where I had been told that my works were quite old fashioned. My work was very, very different when I was 18. But you get taught one thing, and you know, it takes awhile to engage with yourself and develop your own style. You're taught to mimic. At school I was told I needed five pages looking at a certain artist, and to do my own version of the artist.

I found having taught in schools for many years, as a teacher its a tricky one, because you want the students to get the grades. At the end of the day, unfortunately, our society is grade-based. But you also want them to understand that there's far more to it, that the engagement shouldn't be so two-dimensional. So when I got to Brighton, everything shifted. She just happened to be one of the artists I engaged with early on, but by no means the only one. I was really into Peter Doig's work at the time as well. At that point, I loved his work so much that I wanted it to be my work. And you just slowly work through those things, especially if you're working everyday in a studio surrounded by people who are going through the same thing. Everyone has that one artist they really like and really want to be.

It's that age-old tradition again of working your way up as an artist — first under the wings of another great artist, then later standing on the shoulders of other great artists. It only takes about thirty years to break out into something that's very much your own.

But it's true. Thinking about the work I've made for The Deepest Blue, it's actually fairly reflective of the work I did at my five years at Brighton and my first year at the Slade, before things shifted again. It took my awhile to be able to come back to that work, without it feeling like I'm stuck on that work, if that makes sense? A lot of things develop, change and shift, even things in your life.

I developed a real attention to surface. Surface became my obsession. I had to have the exact surface I need to paint on. Things like that, they evolve, and the surface has changed, which has really really shifted the way in which the work comes across.

Are there particular themes you find yourself constantly returning to to explore and rehash?

Definitely. I’m interested in our engagement with landscapes, any landscape. It could even how we interact with this room, for example. I'm interested in how we engage with our surroundings, and this need we have to form an identity within a space, or to latch onto something we recognise within a space.

There is an argument that nothing in the world, especially in the digital era we live in, is going to be unrecognisable. So a true wilderness doesn't exist anymore.

A place where you really can't recognise yourself within it. I think that's something I find very interesting. The human tendency or desire, and I'm completely guilty of this too, of bringing elements from the outside, like botanicals, inside. Or having photographs everywhere. Just having something that feels familiar in your homestead to make you feel at home, and more grounded.

I think in the same sense, thinking about shifting landscapes and collective memory, when a landscape changes for someone, it can be incredibly traumatic. For example, a photograph of something you've grown up with and recognise can be very different to the clear, precise vision you have in your memory, no matter how imprecise memory actually is. I find all of this really fascinating, especially in the context of my own family's history, and my own identity, in terms of travelling and where I feel most grounded.

Where have you seen most clearly this notion of travel and your family history emerge in your practice? Is it tangible, or is it more of a mindset you carry with you when you create?

Probably a little bit of both. I probably see it in my work more than anyone else would.

I did a residency in the Mojave Desert in 2015, and it was my first residency after finishing the Slade. I was going by myself, I was the only UK artist, and I was the youngest. I had to drive, which I hate, by myself, for three hours in a tiny car I had rented in order to get to the desert. They put me in a beautiful house which was really remote. Every artist had their own house, but mine just happened to be the most remote. And you know, we're talking about snakes, coyotes everywhere. And rabbits, really cute rabbits everywhere. But really the wilderness. I love hiking, and I love the wilderness. But I was put in the middle of that, by myself. Whilst I'm a fairly sociable person, and I engaged with the rest of the artists fairly quickly, made great friends with the local musicians there; still I spent a lot of the time by myself with my own thoughts. I was driving for long periods of time alone, which I'm really not used to.

I think, for me, that's the first time what I experienced, maybe, what people in my family could have experienced. It was a vast sort of unknown, a landscape that I was incredibly unfamiliar with. I was also told to wear socks that were higher in order to avoid snakes when you were hiking, I just thought to myself, right — snakes, hiking... I went hiking everyday and I loved it, but you don't think about the power of nature. It's really quite intense to be engaging with that landscape fully and to make work.

I did come across barriers, for example, I couldn't find my ground. It's really important for me to have the right ground. About fifty trips to Home Depot later, I was back at the house experimenting with all of these weird, toxic things to get the surface I wanted to paint on. It was a real challenge, but it really cemented everything — that this was the right direction, this was what I needed to be doing, and that this was what I was interested in doing.

And do these experiences help to set where you've come from and what you're doing into a historical context, so you can make sense of where you're going?

I think so. But I still don't know where I'll end up. Some people can say things like, "oh we'll live in London for the rest of our lives" — but I just don't know.

I've lived now in a few places, and I've enjoyed living in a few places. Every time I leave, I ask myself why I leave. Sometimes I come back to a place thinking that I'm back forever, but then I leave again. So I've given up on myself.

I feel like I've come full circle in terms of family history. My family lives in Singapore, so being able to visit them here is really special, that and being able to study here towards the end of the year.

Which is what I wanted to talk about as well. You'll be taking a Masters in Art Therapy, which is really interesting because it isn't often that someone bridges the gap between artistic practice and going into art therapy. Why was this important for you, and how did it start?

It probably took me awhile to come to, and I think my mum knew from day one.

It felt like a natural progression. I've worked in education, pretty much throughout my time as a student. Teaching and being a practising artist is, I think, very complementary. As most artists know, it's incredibly difficult to make a living, so having a side career that's still creative is important. And I just loved art therapy. Actually I'd always been mulling it over, but I'd done so many years of education so doing another two years of school seemed like a big commitment. So I put it off awhile.

I was actually lucky enough to get a residency here in Singapore at the Winstedt School, which specialises in teaching children with learning differences. They teach a whole array of children, who are all so special, so wonderful, and so ridiculously creative. The nature of the school itself is very creative, and it provides a very arts-led education. I was there for eight months, and I decided to apply for LASALLE's course in Art Therapy because my parents live here and I really enjoy living in Singapore. Compared to other places, I feel that Singapore has so much to offer in relation to this area, because it's still so new and you can do so much to help. I think it's amazing that Singapore is engaging with art therapy.

It almost seems natural to think of art therapy because making art is therapeutic in some ways. So many artists have claimed it to be so, but not many people have wrapped their head around the fact that normal everyday folk could use art therapy as a means as well. What are some of the challenges you've come across, be it whilst teaching at Winstedt or just talking to people about art therapy, in terms of the preconceived perceptions some might have towards art therapy as a discipline?

My mum is a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, and used to be a film maker, so she came from an artistic background and now has a psychoanalytical practice here in Singapore. She did a PhD in Applied Cinema Therapy as well. Growing up with someone who worked in such a creative field and moved into an equally creative field meant that it never felt like an obscure way of communicating. I think art in itself is an incredible communicative and emotional outlet, and a creative outlet, for anyone — children, or adults, or young people who have experienced a trauma or have a disability that makes it hard for them to engage on a vocal level.

The difference between teaching and art therapy is that teaching is very directed. With teaching there's going to be an output, whereas with art therapy, there is no directed outcome.

The idea is that whoever the patient is can explore themselves through this field, and they find their own medium to explore what they need to. It's actually really useful for trauma, which is often very hard to vocally communicate.

Personally, I really understand the benefits of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Whilst right now I think art therapy is the most fitting for me, I'm also quite young. I think it's a fitting way for me to give back, and to work with young people, children, and the older generation as well, if they'd let me. I can see myself eventually, alongside my art practice, going into psychoanalysis and psychotherapy as well, because I think they're so aligned.

Both of them tap into this uncommunicable aspect of the human experience, where sometimes visualising is easier and more accurate than a word-based description. And that's probably where people find the satisfaction, if I may, in engaging in art or music therapy. It's another language that fits all the more acutely what they're experiencing or feeling at the time.

Art therapy is something that's so new in Singapore. There aren't many art therapy practices here in Singapore, and even mental health as an issue is still something that's bubbling underneath the surface. How do you see art therapy fitting into this conversation about mental health in Singapore? Do you see it as a more informal, or more accessible way for people to start talking about mental health?

I think it is, perhaps, a little less daunting. In London, for example, where I live, it's not uncommon for people to be very open about being in therapy. The National Health Service has a lot of art therapists, music therapists and speech therapists working. And here it seems to be just starting to come into the periphery and come into people's awareness.

I think for many people art therapy is a confusing concept. Also, I think people at home don't realise that it's also a talking therapy. It's not purely art making, and neither is it purely talking. It's a combination of both. As with everything, one has to be flexible in their approach. There isn't a collective way to treat a collective problem. Every person is an individual. Whilst you could categorise, let's say, that these children have autism, they are still completely individual. They will all have different traits, reactions, emotions and struggles. This is the same with adults who suffer from trauma. There is no right way to be traumatised. So in this sense, I think art therapy allows people to engage with their problem in a manner that is slightly less daunting.

There can be a huge stigma attached to seeking help, so the idea of sitting down to someone for an hour on end about something you might not even have the words to describe best anyway might be daunting.

Yeah, and I think all of these things take time as well.

And because it's so new to Singapore, it'll be interesting to see the shape and form art therapy takes here.

When I had my interview with Ronald Lay, who's the head of Art Therapy at LASALLE, I was really impressed with him. I think in Singapore, there's a huge amount one can offer in this field in terms of social outreach, which I think is so important. It's also, as an artist, completely separating. I think it's important to engage outside of your own little artistic construct, which can be very insular and quite isolating. You could also really get into your own head, and it's very important to get out of that space and engage.

The artistic community here is small and tight-knit, but it's not as established as compared to artistic communities in cities you've worked in before, such as London. As such, do you feel like it's easier to engage with the community outside of the immediate artistic circle here in Singapore because of how small it is, and how small the country is in general?

Yeah. My experience in Singapore has been nothing but positive in every sense, everyone has been so lovely. I'm really excited to be living and studying here in August. Within the eight months I was working at Winstedt, it was amazing how open people were to engaging with me. For example, Racy — I literally attacked her at the Singapore Art Book Fair.

I forced myself to come to Singapore myself. Which is, I think as an artist, both easy and hard to do at the same time. You can go to openings, where slowly you just meet people, and they introduce you to other people. What's nice is that it's so open here. You can be open about what you're looking for and what you need. I think perhaps because it's such a small country, the only way to engage is to engage with other people.

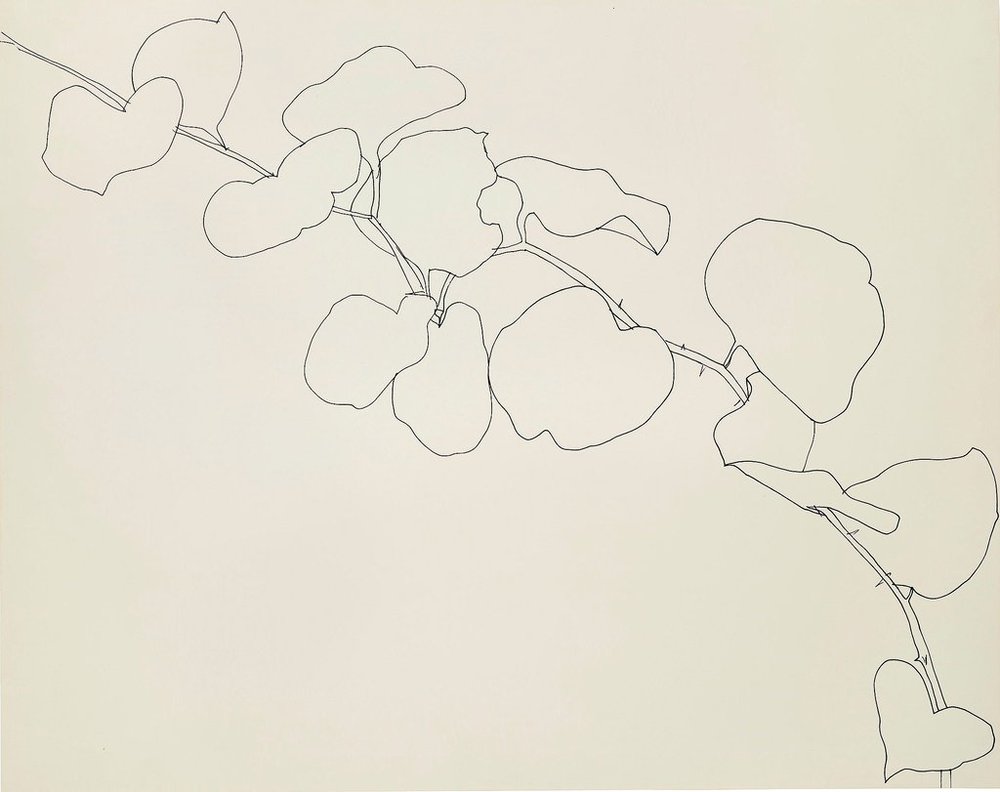

⁷ Ellsworth Kelly, Briar

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, 1961

Do you see your experiences with engaging in art therapy seeping into your own works, or do you see them more as two separate things that you work on in tandem with each other?

I think it's quite hard for me to say now because I haven't started the course yet, so it's difficult to judge how it would change. I have to keep a journal alongside the course, so I'm actually really curious to see how my practice does end up shifting in relation to the course or working full time as an art therapist.

In regards to when I was teaching children, which I find to be correlating path to practicing art, I found that whatever I was teaching the kids fed into my work. When I was in London, I was doing an artist residency, teaching at a school in London for a year and being their artist-in-residence. There was this parallel because I was doing my own work in school whilst I was teaching them. We were looking at Ellsworth Kelly and his plant drawings, and I'm telling you the entire collection of work I made at that school, in hindsight, was completely based on Ellsworth Kelly's works. It's his tone, it's his colouring... Now I look back at the work and its this huge plant and I'm like, oh. But that completely makes sense — I'm teaching it, I'm living it, and I'm breathing it with the students every week.

When I was at Brighton, my work was all about trauma, actually, and from the perspective of a voyeur. I did my dissertation on Frida Kahlo and Francis Bacon, and I was looking at the beauty of landscape if you detach it from trauma. The work then became consciously introspective after that. All my work is very deeply personal, but I think the colour used such a reduced visual language, whether its a repetition of a bird or a plant. All the works I'm displaying at the Gillman show, which are just large, expansive forms, together create the illusion of the landscape, but separately maybe don't. There's a lot of repetition within my work, and a very reduced visual language. A lot of that is to do with what the space around the image can mean. Within repetition, there's a way of mastering control of either a trauma, an emotion or a feeling. Repeating something over and over again is something many artists do. In fact, very few artists don't repeat a similar motif over and over again. Apparently, it is a therapeutic way of containing a form.

Was the move towards a reduced visual language a conscious choice, or was it something that you felt represented your intentions better?

Initially, it was a conscious choice. Before my work started shifting into images and surfaces that were more reduced and flat, I had been doing botanical landscapes that had a lot of depth and were very recognisable as what they were. There was a horizon line, and that was the first thing I got rid of. They were very bordered, and they were landscape paintings, but I felt like it just wasn't enough. I always felt like I had more to say, and that the canvas was quite restrictive.

So that's when I started to work with diptychs and triptychs, because everything had to get bigger. But obviously I'm quite small, so it was difficult for me to make a really huge canvas by myself. So instead, I'd make a really big canvas and triple it so I'd be able to work with this huge surface.

I also like the fact that they're on separate planes, because it almost helps me visualise it more. When it's on one plane it feels constricted again, which I know is completely in my head, but I need it to be borderless and I needed it to be ongoing. There was a point where I thought all of my work was a continuation of the same premise. All the work was one work, but just in separate elements. Then that started to shift again.

⁸ Over pathless hills, Chloë Manasseh

2018

2018

As it does. Do you find yourself drawn to the negative space in your work as well?

Yeah I'm definitely conscious of the negative space. I sometimes fill the space completely, but sometimes the background is more important that the image — it really depends, but it's a consideration.

I'm a very conscious painter. I know what I'm going to paint before I paint it. I've no idea how it'll necessarily come out, but I plan. I do a lot of watercolour sketches, a lot of research, a lot of process goes into the work. Then I choose the size and shape of the stretcher, which I build myself, I have to know that before I start because it takes two weeks to prepare the stretchers for painting. I like the process because it allows me, gives me that time to think. I never used to before. When I did just painting, it didn't matter the size or the shape of the canvas — I just wanted to get something down. But the work now has more meaning more to me.

I'm fairly prolific and I work fairly quickly. But partly to do with what my tutor says, it's important for me to make work that matters. And they might not always work out. In fact, a lot of the time they don't, and I am horrified with what I've done. But I needed to try it. I had this idea in my head festering, and I needed to get it out on paper to see what it meant to me — if it meant anything at all.

Some people see Frankenthaler's work as "colonising space", which I found very interesting.

That's a very strange way to describe her work.

Yeah, but I found it really evocative of empty rooms, where you start filling the space. Which I find really interesting in relation to how people inhabit spaces and their own visual identities.

The way that Frankenthaler's rendering of colours and spaces is sometimes lost when we view her works on a computer screen. But on walls, and side by side with other works, you do see that they expand beyond their borders. In that sense, I guess it does fit into the descriptor of "colonising space", as it infringes onto other areas and takes up more space than assigned.

It sounds fairly intrusive, where she's intruding into her own space in a gallery. There's something about it that's very negative. I found that particular phrase so fascinating, and apparently multiple people have felt that way in viewing her works.

We've been talking mostly about the works you've created for The Deepest Blue, but you've been busy with quite a number of other projects as well. Do you find a sense of rhythm that you're continually moving towards exploring, despite their various different contexts?

I think what was nice about this particular exhibition was being able to directly relate a piece of work to another artist, without feeling like you're infringing on anyone's space. It was nice because I've had ideas in my head for awhile about going back to the more visceral, large landscapes which was what I used about four to five years ago. I've been living with them again as I'm visiting my parents here. It's been really interesting to be confronted by those artworks again, trying to re-engage with what I was feeling at the time, and what came over me to make works like that.

There are times that I feel I have to prove myself as a painter, and show that I can paint. There is something very brave and bold about being able to leave space on the surface, to have these huge expanses space and colour, and to be okay with that. It's the type of work that will divide people as well. People will either get it and be attracted to it, or not. The paintings focus on space and colour, which are two huge considerations of mine.

I've been given the opportunity to do a 25m mural to really just focus in on colour and space as well, which was very fitting time-wise. The ability to be able to use that space, utilise that space, and to allow there to be washes and expanses. You know, I talk about wanting the landscape to be never-ending, well I have 25m now.

Have you done murals before?

This is my first one.

We're excited to see the works you start creating once you embark on your Masters, and it'd be good to regroup to see how your perspectives have changed over the two year-long course. That, and all of your upcoming projects as well.

Yeah, I'm a little scared. I have instalment dates for my projects, but until that day, I just can't really get my head around it. I'm really hoping that from that more opportunities will arise.

I've done a lot installations before, but they were fine arts installations with rooms — taking over a space with sculpture and creating more conceptual spaces. So to do an actual, semi-permanent artwork is quite a huge thing. It'll actually be very golden.