Chunghsuan Lan (b.1991) is an artist from Taipei, Taiwan. He holds an MFA in Fine Arts from Pratt Institute, New York. Lan examines freedom, tradition, restriction, inheritance, universe, and death. His works have been exhibited and collected internationally. He was a resident of Arteles Creative Center, Finland and AIR 3331, Japan.

We met with the artist at Each Modern Gallery in Taipei, where he now works. Just in the gallery space next to us, his works, Lockdown Universe, are shown alongside works by Nakahira Takuma and Barbara Kasten. For our interview, Lan chose to begin with four incredibly different works of art: Andrea Mantegna’s The Lamentation of Christ, Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Bay of Sagami, Atami, and Tetsuya Ishida’s Awakening.

We met with the artist at Each Modern Gallery in Taipei, where he now works. Just in the gallery space next to us, his works, Lockdown Universe, are shown alongside works by Nakahira Takuma and Barbara Kasten. For our interview, Lan chose to begin with four incredibly different works of art: Andrea Mantegna’s The Lamentation of Christ, Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Bay of Sagami, Atami, and Tetsuya Ishida’s Awakening.

I was really intrigued by your selection of artworks — they’re quite varied in terms of their style and the time period in which they were made. Why were you drawn to choosing these four?

I feel like my selection of artworks here represent different aspects of my art and my personal philosophy. In these works, you can see death, idealism, and social issues. Initially, I was trying to look for an artwork that said it all — but I couldn’t, because I believe that an artist’s concept cannot be reduced to a single layer of meaning. As a result of that, I selected a couple of artworks to create a sort of gallery.

I’ve been trying to explore something very universal through the sort of art I’ve been making — through history, through those who have lived through it or felt it.

I think that’s why I chose these four artworks. They’re also really dark, and I like that. It’s a personal preference.

Now that you’ve pointed out the darkness in the artworks, it’s become incredibly obvious to me. Despite it, I see a very strong focus on light and how it falls on the body.

I studied photography at an undergraduate level, but I wouldn’t call myself a photographer. I call myself an artist, and I think that influences how I see these artworks. You can see that the paintings that I’ve chosen here are rather photographic, in some way.

Why do you say that you’d identify as an artist but not as a photographer?

I don’t see the point of categorising myself as a photographer. Photography is art, but I don’t know why audiences have tended to set one apart from the other. I do feel like I’m an artist. When I was in New York doing my MFA in Fine Art, I used photography as a medium or a tool to express what I was trying to say. However when I got back to Taiwan, people would describe me as an “emerging photographer”. I don’t like that term.

It’s really interesting that you say that because focusing your art or specialising in a particular medium can be something that defines an artist’s practice, and you seem to be moving away from that labelling process.

Shifting away from categories is something that you’ve been doing with your works as well, and that’s something that’s reflected in your international choice of artworks for this interview. Why was moving your art in a direction that’s universal important to you? Was it a change, or did you start out knowing that you wanted to create art that was universal?

It’s quite common for photographers to travel to and photograph developing countries. I’m not sure if that’s career driven, but my sense is that it’s none of their business to be doing that.

When I was in graduate school, I tried to make art that was related to my hometown. I started making art by thinking about what mattered to me — and that included my hometown. I was in New York trying to make art about Taiwan and it was really difficult because I was far away from it in a physical sense. It would be tough trying to get inspiration. I spent one or two years making art about [home].

However, I started to think about how I built my artistic philosophy on how similar human beings are, and how we are all part of the same universe I knew I had to stop creating works about home. I removed all the Taiwanese features in my artworks, and began making art about the universe.

That really affected how I approached photography as well. Another thing about having gone to the Pratt was that we were allowed to take every class available. Although my classmates worked in sculpture or painting, they all really saw themselves as artists. We gave each other advice all the time, and that really helped to shift my perspective. It made me realise that I couldn’t limit myself to being a photographer. I just wanted to be someone who made art — an artist.

I move back and forth between my medium and my concept. If I don’t want categories such as “Taiwanese” or “Chinese” to define me, then perhaps I shouldn’t categorise my medium as well.

¹ Declaration of _ (_宣言), Chunghsuan Lan

2017

2017

Do you think a fully universal artwork is achievable?

Does the resulting interpretation or response of the audience matter then to you?

I think so, because I don’t want people to see my artwork as coming from a particular place. I also feel like the more minimal one’s art is, the more universal it becomes because one hasn’t included specific characters in it.

² The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Andrea Mantegna

Pinacoteca di Brera, 1490

³ The Death of Marat, Jacques-Louis David

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, 1793

In comparison, some of the other works you’ve selected for this interviews are full of character — two of them depict the deaths of well known figures.

Death is something that you’ve dealt with in your own works as well, which is an incredibly delicate topic that can be deeply personal to some. How do you get access to photographing these moments, and how do you do it in a manner that is sensitive to not just the dead, but the living?

I’m a rebellious person, and I don’t believe in or subscribe to any religion. When I see the painting, The Lamentation of the Dead Christ, I feel the presence of a human body. Because of the vulnerable angle at which Andrea Mantegna chose to depict this moment, I don’t feel like I’m encountering a god. The work really encapsulates how I see death. Death is, simply, just death. I know that Mantegna obviously didn’t see it that way because he painted for the church, but that’s just how I see it.

With The Death of Marat, I feel it comes down to my background. As a Taiwanese, I’m aware of the political issues that face the country. No matter how hard we try to claim Taiwan as the Taiwanese people, it remains a really difficult matter due to the restrictions we face. I’ve had conversations about this with my friends, who have mentioned that suicide can seem like an option when there are no clear paths towards achieving your dreams. Marat himself was assassinated, but I almost feel like when one’s desires seem unachievable in this lifetime, death can seem like the only way out. Marat was also an important figure in the French Revolution, and my works have been concerned with the idea of freedom. Being born Taiwanese, my family and school taught me to be Taiwanese. But I don’t want that.

When my grandparents passed away, I didn’t feel anything. I wasn’t sad. It dawned on me that perhaps I was able to view death objectively. I also hate how funerals are done sometimes. Hours can be spent standing there with monks conducting rituals. It no longer felt like a ceremony for my grandparents. It seemed like a show for the living, a stage to perform our family’s kinship. We even hired a host for the funeral. The host said things such as, “Now that the deceased has departed us, you might be thinking of the book on his desk — half-read”. But my grandfather had been paralysed for a year prior to his death — it wouldn’t have been possible for him to have left a half-read book on a table. That helped me to realise that I wanted to create something that discussed the topic of death.

Asian cultures, especially, see death as taboo. It’s something that people don’t like talking about, and that’s why I want to push it.

That’s why I say that I’m a rebellious person. I want to show people death, even if it’s uncomfortable for them.

For the Dielusion series, I had to have conversations with people to persuade them to participate. I asked them what their ideal death looked like, they would tell me, and I would photograph it.

How was that process like? Were there things that were lost in translation, or was the collaboration process quite an open-ended one?

Most of the people I worked with for this project didn’t speak good English, so I spent a lot of time trying to figure out what they were trying to say. I found that young people were eager to participate. Many of them mentioned feeling lonely, although the project was not about loneliness. With middle aged participants, they sometimes got angry with my questions. They felt that opening up about what an ideal death looked like for them would constitute making themselves vulnerable. I had never seen it that way before.

When shooting, I’ll arrange the scene according to their descriptions and have them lie down. Right before taking the photograph, I’ll change something. I wanted to include the notion of compromise in these images because it isn’t possible to achieve a death that is fully perfect. It could be something as simple as moving the participant’s leg slightly out of place.

How did the participants take it? Did they notice the change?

The photographs were exhibited, and one of the participants came by to see it. She saw the image and cried. Maybe I had photographed her death too beautifully, but she said that she felt touched. It definitely wasn’t a positive emotion, but she felt moved in some way. I’ve gotten positive feedback from most of my participants, but I’m not sure if that’s just them being polite.

⁴ Dielusion: Kunio, Chunghsuan Lan

2017

2017

You’ve done quite a few projects exploring the topic of death now. Do you think you’ll be approaching it from a different angle for a future project?

I think so, but I don’t have something in mind at the moment. I’m actually working on something different now. I’ve thought about death since I was a child, but I don’t really know what I should look at next.

I work on it as a series because I think about it everyday. Maybe I’ll end the series when I get a total of 44 photographs — 44 for its association to death in the Chinese language. But for now, this is the only project I have that relates to death.

Photographers tend to work in series because it’s something that the medium lends itself to. In your personal experience, how do you know when you’re done with a particular series of photographs?

When I feel tired of it, or if I feel that I’ve done enough on the subject. With Lockdown Universe, I only made five images because I felt like that was sufficient. With another series, Stardust, I based it on NASA’s research on star systems that potentially contain life. Because the report looked at multiple star systems, approaching the work as a series was natural. With Dielusion, I think it’ll be an ongoing project as long as I feel like creating more images about it. As soon as I feel like I’m done with the concept, I’ll stop.Bringing in another work I chose for this interview, Sugimoto’s photograph, for example, is part of his larger Seascapes project. It feels like that project will last him a lifetime. With projects like that, there isn’t a clear end in mind. In a similar sense, if I want to make something, I’ll continue to work on it.

⁵ Bay of Sagami, Atami, Hiroshi Sugimoto

1997

Hiroshi Sugimoto is an incredibly prolific artist with decades worth of work under his belt. Why were you drawn to picking out this particular work of his?

This photograph feels very universal to me. I like his Theater series and the series he did where he photographed wax figures as well, but I find myself fascinated by the ocean. I don’t really know why. There’s just something there that I can’t explain. In a similar sense, I find that Sugimoto is the only artist whose works I really like, but can’t really explain why.

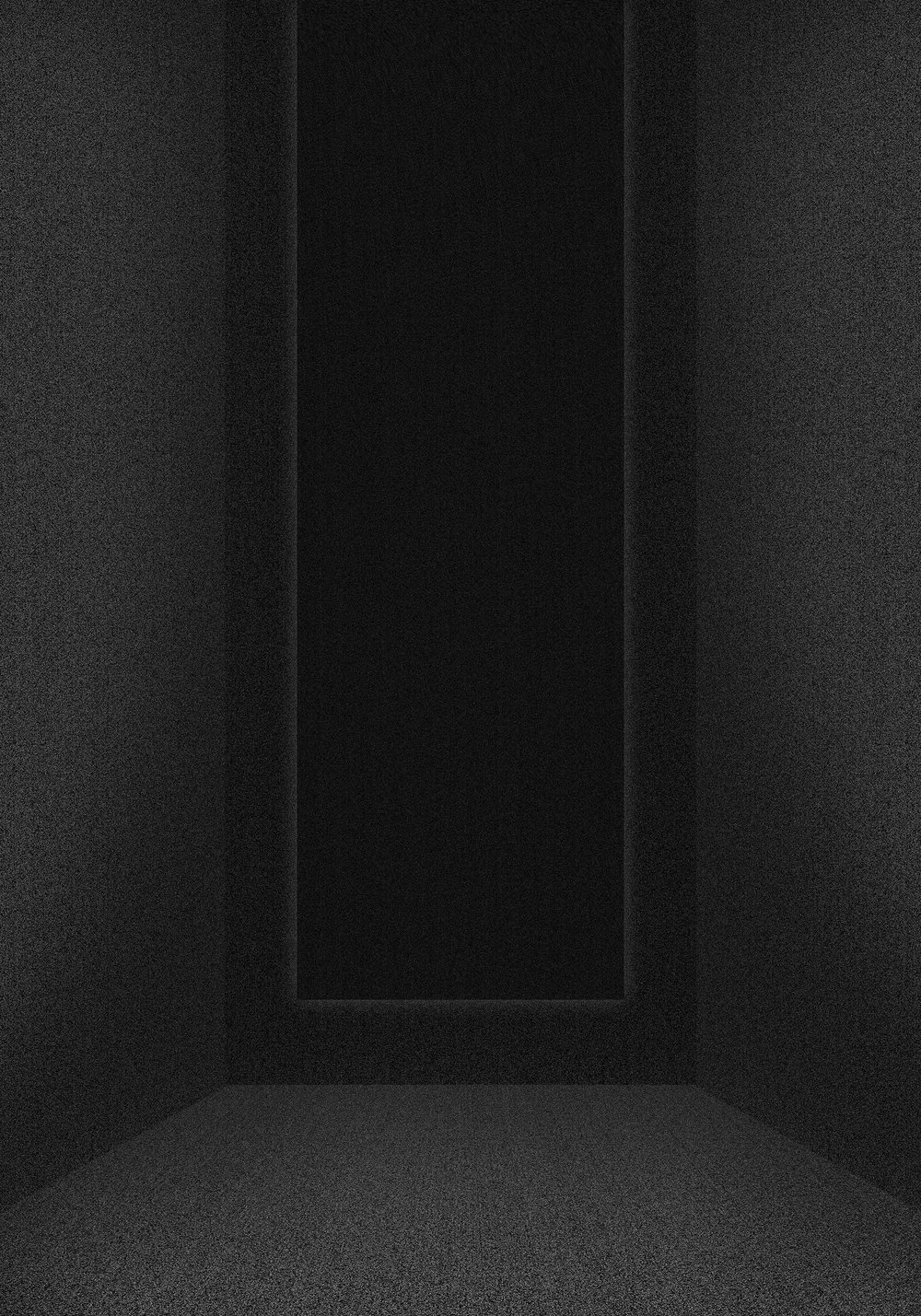

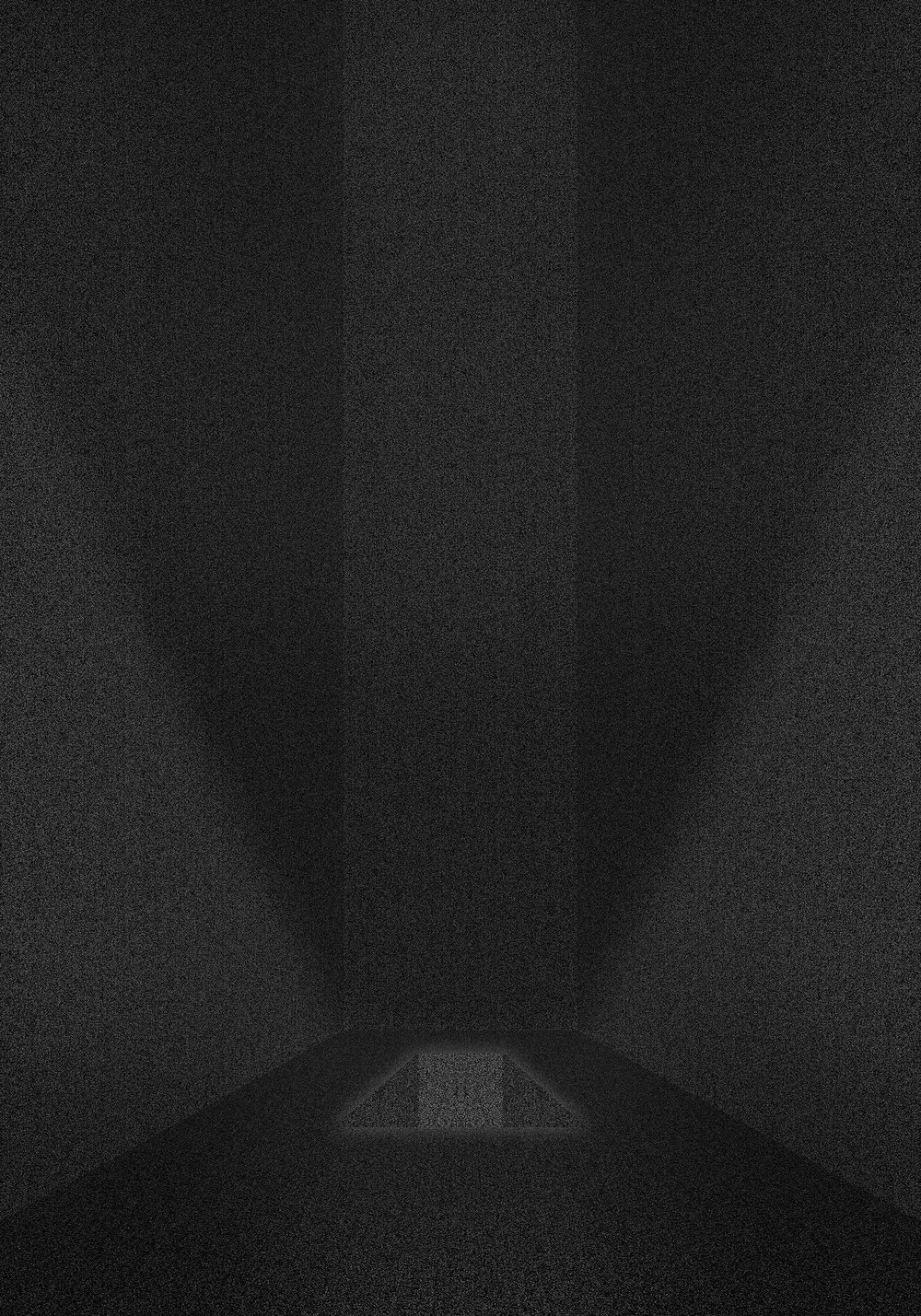

When you look at the works I create, most of them are dark and shot in black in white too. Most of my works touch on the fact that I’ve been restricted by how my childhood and my family has subconsciously influenced me. For example, Lockdown Universe is a space I’ve created based on the bathroom that my Mum used to lock me in as a kid. Gradually, I got used to the darkness and I’m now no longer afraid of it. In fact, I like the darkness. So maybe now that I’m older, I’m drawn to darker works such as Sugimoto’s. There isn’t a concrete reason.

I know that I have specific tastes and preferences, but I also acknowledge that if I had been born into a different family, these tastes and preferences might have been very different. I might have enjoyed the works of Takashi Murakami more.

⁶ Lockdown Universe: The Door, Chunghsuan Lan

2017

2017

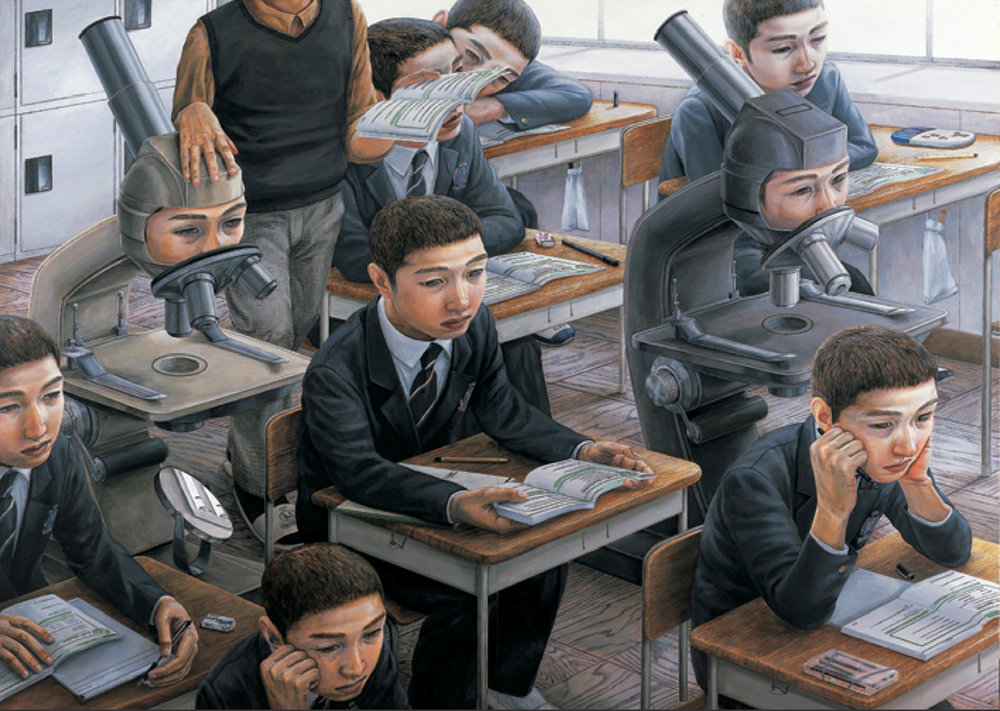

⁷ Awakening, Tetsuya Ishida

La Biennale di Venezia, 1998

Alongside the photograph by Sugimoto, you chose a work that is driven by and comments on social issues — how life is like in a fast-paced, modern society such as Japan’s. In terms of geography or culture, Ishida’s work is specific and particular, which almost sits at odds with the universality you speak of in Sugimoto’s and your works.

How do you balance wanting to say something that is of value to society, and remaining true to your artistic philosophy of universality?

What I’m doing now is to explore them individually through different series. I don’t think that the two goals can be combined.I feel like my selection of artworks almost represents a process for me: from how I deny religion (The Lamentation of Christ), to how I see death (The Death of Marat), and to how I feel about Asian society (Awakening). After all of that, hopefully we can arrive at something universal, like Sugimoto’s work.

I feel like it would be really difficult to combine both a social angle and a universality in my works — at least for now.

It’s not just two different concepts, but it’s also about a difference in style as well.

I know some artists spend fifty years labouring over a single concept, but I don’t want to be that sort of artist. I can use whatever medium I want to use to talk about what I want to talk about.

I think the two concepts are related, but to create a visual artwork that connects the two directly would be difficult. I enjoy making works that are more minimal at the moment, but the challenge is in giving these works a point such that the viewer can start to understand what I’m trying to say.

Universality aside, is there a reason why you find yourself drawn to a more abstracted and minimalist style?

Sometimes I feel like I don’t want to talk too much, or tell the viewer too much.

I believe that every artist is made up of varying facets. I could be exploring one issue through a particular work, but there still remains other aspects to my practice that aren’t being discussed. I have worked on many series, and all of them are different. Most of the people I know say that despite the differences between them, they’re still able to attribute these works to me. To have achieved that is a great success for me.

⁸ Lockdown Universe, Chunghsuan Lan

2018, Each Modern Installation View

Photograph from the artist

⁹ Lockdown Universe, Chunghsuan Lan

2018, Aki Gallery Installation View

Photograph from the artist

2018, Each Modern Installation View

Photograph from the artist

⁹ Lockdown Universe, Chunghsuan Lan

2018, Aki Gallery Installation View

Photograph from the artist

Have they ever mentioned how they see these works as being related to you, or which aspects of these works they identify with your practice?

They say it’s the atmosphere.

Another thing about your works is that you often modify your works to fit a particular exhibition space. In doing so, you step into the shoes of a curator, so to speak. Why is it so important for you to take charge of such spatial considerations?

I just curated a show for my friend where I asked her to change almost 80% of her works. The show opened two days ago, and I was asked about this quite a bit then as well.

Most of my works come in two editions: one for the collector, and the other is site-specific. For me, it’s important that the viewer gets the experience of being in the whole space — and not just the experience of encountering my works.

When my works are shown in a space, ideally it should relate to the physical venue. The viewer shouldn’t be standing in front of my works trying to get a sense of what it is trying to say. The whole experience should feed into it.

When you create images, do you find your artistic processes influenced by your experience with curating shows?

I begin my process by thinking about how I want the final work to look like. I imagine how I want it too look like within a space, and thereafter adjust my work accordingly. For me, group shows aren’t ideal because I create all of my images with solo exhibitions in mind.

When I curated the show for my friend, some viewers asked me if I thought the show constituted a new creation. I think it is, because it resulted in something new. When I curate the works of fellow artists, I always ask them to change something. I think how the work is displayed and how the viewer sees it is really important.

How do you balance that with what the artist wants to say with their work?

I try to stay with their concept, and I think that’s the main point. You have to convince the artist that by changing the work, it further enhances their original concept. My suggestions challenge their methods, but do not challenge their concept. Most artists I work with end up taking my feedback onboard because they understand that I’m approaching this from a constructive angle.

Having curated a couple of shows before, are there particular spaces that you feel your works won’t fit into, or are you up for the challenge in terms of making something unconventional work?

Although I don’t see myself as a commercial artist, there are some non-profit galleries in Taiwan that I probably would not display my works in. My standards are quite high with regard to the installation of my works, so it’s quite important for me that this is done professionally.

You’re now working with Each Modern Gallery, and I’m curious to know if being in close proximity with the art market has influenced how you understand your own practice.

Not yet. I would describe myself as idealistic. I don’t want to be controlled by the art market, which is similar to how I feel about being controlled by my culture. I don’t feel the influence yet, and I’m still doing my own thing.

Many artists have, for practical reasons, taken up commercial jobs alongside their artistic practice. As a result, making art sometimes becomes secondary to their day jobs. How has it been occupying commercial and art making roles simultaneously?

I worked full time in New York whilst doing my graduate school as well. I believe that if you are passionate about your art, you’ll make it work. I’m okay with my job at the moment, even though it means that I now have less time for art making.

As a result of working at Each Modern, I’ve gained access to resources such as metalworkers and framers. Prior to working here, I didn’t have these contacts, but now I can get in touch with them easily. That’s the upside of my job here; but in terms of having the time to make work, I definitely have less time now. Time is especially important when working in photography, one needs time to go out and make pictures.

This will probably be the last year I’ll allow for my practice to be defined by the term “photographer”. I don’t plan to participate in photography festivals or exhibitions next year, and will be working on sculptures and installations. I’ll be working with fabricators and factories to create these large metal structures.

I can imagine that it would be incredibly difficult for someone who works in painting to hold a separate day job, but it’s alright for me at the moment.

What were the motivating factors for your move towards sculpture or installation works? Why choose to work in sculpture and installation instead of other mediums, such as painting?

Well firstly, I’m terrible at painting. I can’t paint. I’ve made videos and moving images before, and some will be shown in Taiwan later this year. I’ll be working with another artist on a dual-solo showcase, and I think it’ll be great.

I just don’t feel fascinated by photography anymore. I love the printed product, but I don’t really want to take pictures now. Going to graduate school also pushed me towards branching out.

There is no way a single material can say everything one wants to say.

If my art has been about making different series to encompass different aspects of my practice, maybe I can use different materials in a similar manner.

I also don’t trust photography that much. Photography fascinates people, and this fascination can blind its users. One takes pictures without much consideration. Although many of my series comprise of photographs, I’ve tried to insert a deeper discussion about the medium into them. For example, I tried to imitate crime scene photography with the Dielusion series. Photography is something that’s easily approachable, but it’s meaningless to me to simply take pictures. If the concept I’m trying to drive at can’t be said through photography, I won’t use it. Coincidentally, most of my works take the form of photographs and moving images at the moment.

Do you think this suspicion or wariness of photography as a medium keeps you moving forward in terms of further developing your practice?

I think so. The other reason relates to the fact that my practice is concerned with the pursuit of freedom. As mentioned before, I don’t want to be labelled. If I could paint, perhaps I would paint.

I’ve always had this concept of utopian freedom where every human being is free to be whomever they want to be.

Perhaps one day we’d be able to choose our preferred nationality. We’d simply just choose one. Because of this, I feel like I’m flexible with regard to the medium I work in. I don’t want to be labelled, categorised or restricted.

Do you have, in mind, an ideal artwork, an ideal state of art making and an ideal response towards your works?

I probably won’t be able to achieve my goal of universality and freedom in my lifetime. Every time I attempt a work, there will be an imperfection within it that will push me forwards, and forwards, and forwards. It will never be enough.

You’ve spoken so much about idealism and utopian thoughts on freedom, and I wonder if you have in mind a place of perfect freedom and how that looks like for you? Is the sort of freedom that drives your practice one that has no strings attached to it; or are there defining factors?

I just feel like I want to escape. I want to escape Taiwan. This place has restricted me too much, so a freedom from Taiwan is one of the freedoms I’m seeking out.

Before I lived in European and Western cities, I thought that aside from its political issues, Taiwan was a rather laid-back place. I was struck by the political climate and social issues, such as racism, prevalent in cities such as New York. I really hated that sort of thing, so freedom from such matters would probably be something I’m looking for as well. It obviously still happens there, and it happens here in Taiwan as well. It always leaves me wondering why people can’t live the lives they want to live.

There might be a circumstance under which one can experiences true freedom, and it probably would come with isolating oneself from society. That sort of lifestyle probably isn’t for me, because I’m still a very materialistic person. Or maybe a little bit. Since I can’t extract myself from society, stating what ideal freedom looks like becomes a statement of ambition.

An Italian friend of mine mentioned to me once that Taiwan seems like the place in Asia where people can live freely. I’m just wondering if we can push it a little more so we can truly be a multicultural paradise.