Colonial Imprisonment and Capitalist Imaginations: Museum Architecture in Singapore

BY ALFONSE CHIUShare: ︎ ︎

“Museums are democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures.”

— INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF MUSEUMS I. NOTES ON HISTORY

Before there were museums, there was first the museological impulse: a deep, intrinsic human yearning to remember what had passed; to document stories and make permanent in some forms these fleeting impressions; and, to make a space where one could look backward even as one resolutely moves on — in time, in history. From the rock carvings of the Kamyana Mohyla to the cave paintings of Lascaux, from the Palaeolithic cave art in Borneo to cuneiform tablets in the libraries that dotted the landscape of Mesopotamia, one could see that the desire to preserve and disseminate knowledge is almost as old as the very notion of it.

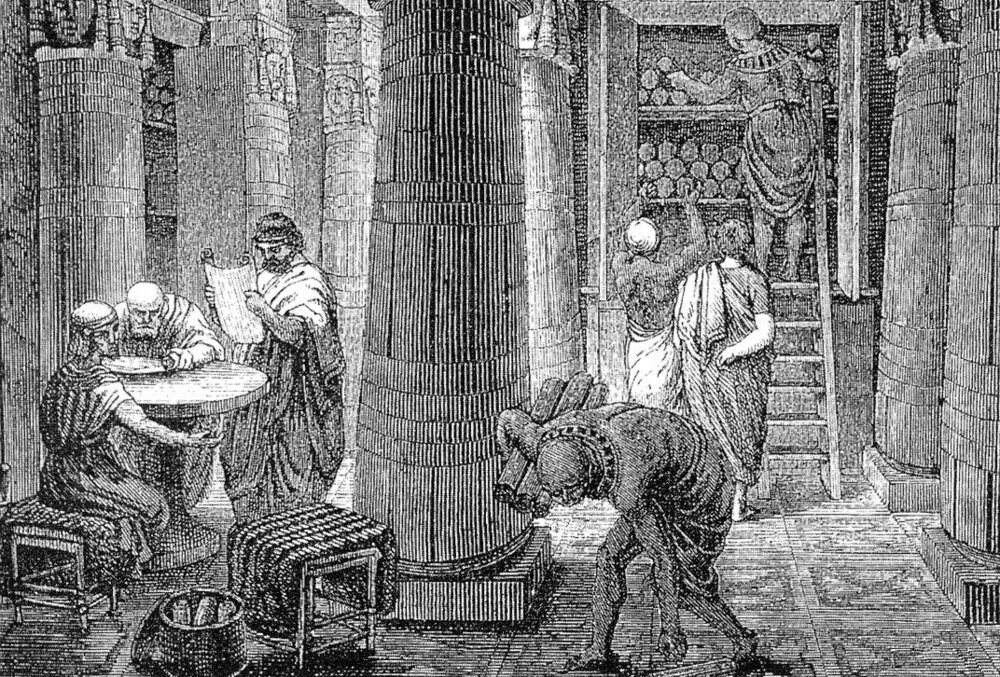

If we are to examine a museum from its etymological roots, we can trace the story to ancient Egypt, where the Mouseion was founded in the magnificent city of Alexandria by Ptolemy II Philadelphus, and supported by the patronage of the royal clan. Meaning quite literally the ‘seat of the Muses’, who were the inspirational goddesses of knowledge, the Mouseion was not quite what we would think of when we think of the museum in contemporary times: it had no great works of art, compared to the collection being assembled as the competing Library of Pergamum. Instead, it was an intellectual centre anchored by the presence of a school and a library, much like what would come to connote a university. The focal point of the Mouseion was not the accrual of artefacts, instead the bedrock underpinning most of its activities was the gathering and consolidation of knowledge and texts from across the world — a quest for meaning, not material, in a manner of speaking.

¹ Library of Alexandria in the Mouseion

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

² Altertümer von Pergamon, Richard Bohn

Heidelberg University Library, 1885

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

² Altertümer von Pergamon, Richard Bohn

Heidelberg University Library, 1885

A definition of what a museum could, would, and should constitute that is closer in tone and function to its current usage grew more apparent only much later on during the Italian Renaissance, when the prevailing cultural conditions of the time and prosperity prompted a renewal of interest into past glories and the aureate historical genealogy from whence the Italian traditions had sprung. With the great dynasties — Gonzaga, Medici, Sforza etc — commissioning and collecting on a grand scale, the museum’s focus shifted somewhat from the subjects of yonder to objects and miscellany that were to prompt as much scholarship as awe at these blatant demonstrations of wealth. Two Italian thinkers in the 16th century, the philosopher Giulio Camillo and the scholar Ulisse Aldrovandi, would come to influence the perception of the museum profoundly, with plans that elaborated on the theatricality of organising and representing knowledge.

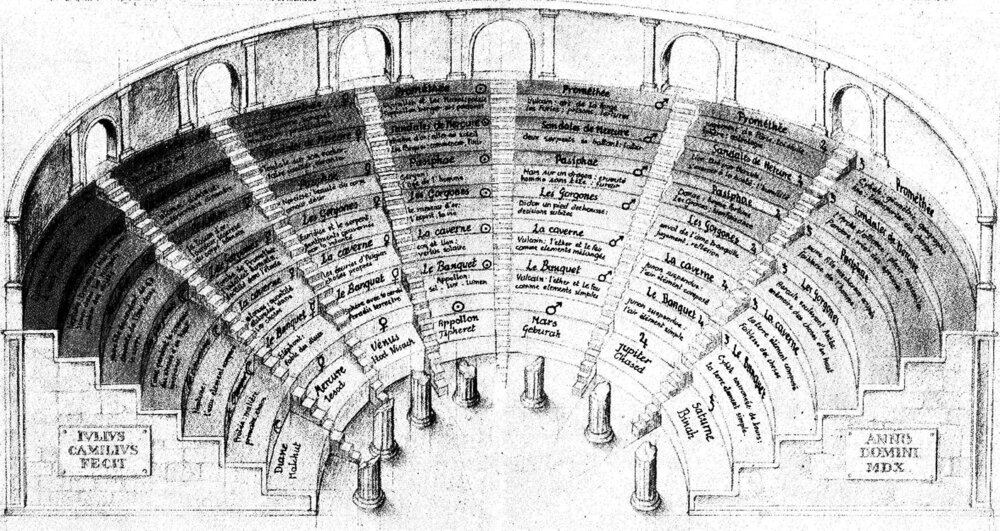

Described in his posthumously published L’Idea del Theatro, Camillo’s proposition for a ‘theatre of memory’ is an architectural structure meant to “tener collocati e a ministrar tutti gli umani concetti, tutte le cose che sono in tutto il mondo;” or, to locate and administer all human concepts, everything which exists in the whole world. Referencing the Vitruvian description of the Roman theater in De Architectura, Camillo toys with the relationship between the stage and the audience, and reverses the directionality of spectatorship by situating the perspective of a would-be viewer on the stage gazing at what would have been the seats, repurposed to house an archive of individual nodes of knowledge organised based on mnemonic principles. Camillo’s theatre of memory is divided into seven lobes, each illustrated on the lower level by an image referring to one of the seven planets, and is positioned on seven levels of steps that cover a total of forty-nine areas, each associated with a mythic figure from occult. The entirety of humanity’s knowledge would be archived on the different levels of this half-circle, and retrievable through mental associations with the various visual cues — Camillo himself describes this theatre as a mens fenestrata, literally a “mind endowed with windows,” much like a brain with portholes. Laden with meaning even in its construction, the structure itself was to lie on seven pillars, referring to the buttresses that supported the biblical Solomon’s House of Wisdom.

Radically different from the occultism of Camillo’s visualisations is Ulisse Aldrovandi, commonly regarded to be the father of modern natural history studies, whose ethos for collection and display had been that of the amassment of biological materials and natural artefacts, with the magnificent ambition for the complete dominion of all aspects of natural knowledge in the name of science. The method was systematic, but the endgame was encyclopaedic, reminiscent of the works of Pliny the Elder and his pursuit for definitive, objective judgement, much of it prompted by the sudden urgency of the discovery of the New World, and progressive breakthrough that revealed heliocentricity and a universe that no longer exists around the ego of humanity. In roughly the same period, Germany witnessed the rise of the Kunstkabinett, or cabinets of curiosity, that spotlighted the process of collection, and showcased collections of all sort — most often with a kind of casual whimsy that belied the proto-scientific manifestations of inquisitiveness. Here, the key difference between the Italian and German was that of purpose: in both cases, the Italian sought to rationalise, to systemise, and synthesise a grand vision of knowledge, and then subject it to human control; the Germans were much less ambitious, and sought to entertain, not edify, even as these assemblages commonly reveal the deep intertwining mechanics that bind the artificial to nature — mimesis — and how essential qualities of objects could be represented — diegesis.

Described in his posthumously published L’Idea del Theatro, Camillo’s proposition for a ‘theatre of memory’ is an architectural structure meant to “tener collocati e a ministrar tutti gli umani concetti, tutte le cose che sono in tutto il mondo;” or, to locate and administer all human concepts, everything which exists in the whole world. Referencing the Vitruvian description of the Roman theater in De Architectura, Camillo toys with the relationship between the stage and the audience, and reverses the directionality of spectatorship by situating the perspective of a would-be viewer on the stage gazing at what would have been the seats, repurposed to house an archive of individual nodes of knowledge organised based on mnemonic principles. Camillo’s theatre of memory is divided into seven lobes, each illustrated on the lower level by an image referring to one of the seven planets, and is positioned on seven levels of steps that cover a total of forty-nine areas, each associated with a mythic figure from occult. The entirety of humanity’s knowledge would be archived on the different levels of this half-circle, and retrievable through mental associations with the various visual cues — Camillo himself describes this theatre as a mens fenestrata, literally a “mind endowed with windows,” much like a brain with portholes. Laden with meaning even in its construction, the structure itself was to lie on seven pillars, referring to the buttresses that supported the biblical Solomon’s House of Wisdom.

Radically different from the occultism of Camillo’s visualisations is Ulisse Aldrovandi, commonly regarded to be the father of modern natural history studies, whose ethos for collection and display had been that of the amassment of biological materials and natural artefacts, with the magnificent ambition for the complete dominion of all aspects of natural knowledge in the name of science. The method was systematic, but the endgame was encyclopaedic, reminiscent of the works of Pliny the Elder and his pursuit for definitive, objective judgement, much of it prompted by the sudden urgency of the discovery of the New World, and progressive breakthrough that revealed heliocentricity and a universe that no longer exists around the ego of humanity. In roughly the same period, Germany witnessed the rise of the Kunstkabinett, or cabinets of curiosity, that spotlighted the process of collection, and showcased collections of all sort — most often with a kind of casual whimsy that belied the proto-scientific manifestations of inquisitiveness. Here, the key difference between the Italian and German was that of purpose: in both cases, the Italian sought to rationalise, to systemise, and synthesise a grand vision of knowledge, and then subject it to human control; the Germans were much less ambitious, and sought to entertain, not edify, even as these assemblages commonly reveal the deep intertwining mechanics that bind the artificial to nature — mimesis — and how essential qualities of objects could be represented — diegesis.

³ Reconstruction of Giulio Camillo’s Theatro della Memoria

⁴ The Louvre Credit: Unsplash

⁴ The Louvre Credit: Unsplash

The idea of the public museum would not truly take off until the French Revolution, when the National Assembly decreed that the Louvre was to become a public museum, the first of its kind, and seized control of the royal collection house there almost simultaneously while Louis XVI was imprisoned. Opening on the first anniversary of the end of the monarchy in 1793, the beauty of the Louvre and the art it contained was to become a model of virtue for the French public to emulate, and convey an irreducible sense of national belonging. Housed in a historical structure that almost organically evolved with each iteration of its occupancy, the Louvre stood for both the permanence of the French identity, and the mutability of how it could be defined. On a more important note, the opening of the Louvre also signified that knowledge, and all that it entails, is now a public resource availed to everyone.

Museums and their construction would grow to be a much more popular endeavour in the 19th century, with European capitals welcoming architecture and accents cribbed from the annals of building throughout Western history. Featuring elements such as pediments in the classical style and Roman pilasters, the museum was not to merely house the past, as much as embody it, imposing the triumphant narrative of imperial lineages upon the developing urban-scape. The Naturhistorisches Museum Wien and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, designed by Gottfried Semper and Carl Hasenauer respectively, and commissioned by Emperor Franz Joseph I, were great examples of the historicist style that fused the palace and the museum into the palace-museum — tremendous mergers of cultural and political might that harkens to the glorious past. Dreamily referential and nostalgically oriented, these buildings found their balance between its content — commonly spoils of colonial excursions, or otherwise looted from unfortunate populations — and its form. Even in modern times, entering such structures still carries a certain patrician awe for the powers that managed to ravage and dominate, and an unease at the underhanded cruelty that must accompany such triumphant nationalist narratives.

Museums and their construction would grow to be a much more popular endeavour in the 19th century, with European capitals welcoming architecture and accents cribbed from the annals of building throughout Western history. Featuring elements such as pediments in the classical style and Roman pilasters, the museum was not to merely house the past, as much as embody it, imposing the triumphant narrative of imperial lineages upon the developing urban-scape. The Naturhistorisches Museum Wien and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, designed by Gottfried Semper and Carl Hasenauer respectively, and commissioned by Emperor Franz Joseph I, were great examples of the historicist style that fused the palace and the museum into the palace-museum — tremendous mergers of cultural and political might that harkens to the glorious past. Dreamily referential and nostalgically oriented, these buildings found their balance between its content — commonly spoils of colonial excursions, or otherwise looted from unfortunate populations — and its form. Even in modern times, entering such structures still carries a certain patrician awe for the powers that managed to ravage and dominate, and an unease at the underhanded cruelty that must accompany such triumphant nationalist narratives.

⁵ Naturhistorisches Museum Wien

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

⁶ Kunsthistorisches Museum

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

⁶ Kunsthistorisches Museum

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The imperial fantasies would collapse just a couple of decades later, emerging from the gloom of a war-torn 20th century thoroughly disillusioned at the bloodied rubble that finally ended all hopes of a golden return. However, beneath the shell-shocked and pock-marked cityscapes also lay the pragmatic realisation that with obliteration comes the possibility of rebirth, tabula rasa. In the wake of trauma, the Modernist architects of the impending millennium found agency in the negotiation of remembrance, claiming inspirations but not duplications of the designs from the past, much unlike the comparatively maudlin attempts of the historicists who sought homage but produced kitsch, however grand they maybe. Le Corbusier and Auguste Klipstein would undertake their Grand Tour in the early 1900s, and Le Corbusier would produce the legendary sketches of Acropolis that recognised and refracted the monument and the landscape from which it seemed to arose, finding an organic yet logical vernacular in the ways the ancients built their buildings.

Before the first of the modern museum — Frank Lloyd Wright's fantastic, seminal rendition of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum — was to emerge, a well-studied spatial predecessor lead the way: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich's German Pavilion for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, Spain, recreated by dedicated Catalan acolytes in the mid-1980s, marked an important chapter in the Modernist conception of space with its simplicity and understated luxury. Open but subtly reserved, its glass walls function as both partition and filter, directing the movements of visitors with a practised ease that draws into sharp relief our own bodily agencies and their conditions for occupying and traversing a space. Three decades later, the Guggenheim would open and chart a grand new vision in the way that a museum could be.

Modelled after an ascending helix, the Guggenheim, mononymic in the way of celebrities, split from the traditional axioms of angularity in favour of an upwardly mobile aspiration that forces visitors to follow its trajectory and view art history as a process of unescapable progression. By doing so, Wright shrewdly creates a third option from the standard narrative of the museological space — either the camp re-enactment of the historicists, or the neutered, neutral white cubes of the modernists — and posits that the space of the museum carries meaning unmoored to the works it contains; if it is not the presence that denotes meaning, then surely it must be the absence, after all we do notice what is not here as much as what is here. The intersections between the space and its occupants — the works, the audience — make visible the contestations of meanings and semantic impositions whilst still allowing for a degree of freedom in articulating a point-of-view not necessarily prescribe by the space or the curators.

Before the first of the modern museum — Frank Lloyd Wright's fantastic, seminal rendition of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum — was to emerge, a well-studied spatial predecessor lead the way: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich's German Pavilion for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, Spain, recreated by dedicated Catalan acolytes in the mid-1980s, marked an important chapter in the Modernist conception of space with its simplicity and understated luxury. Open but subtly reserved, its glass walls function as both partition and filter, directing the movements of visitors with a practised ease that draws into sharp relief our own bodily agencies and their conditions for occupying and traversing a space. Three decades later, the Guggenheim would open and chart a grand new vision in the way that a museum could be.

Modelled after an ascending helix, the Guggenheim, mononymic in the way of celebrities, split from the traditional axioms of angularity in favour of an upwardly mobile aspiration that forces visitors to follow its trajectory and view art history as a process of unescapable progression. By doing so, Wright shrewdly creates a third option from the standard narrative of the museological space — either the camp re-enactment of the historicists, or the neutered, neutral white cubes of the modernists — and posits that the space of the museum carries meaning unmoored to the works it contains; if it is not the presence that denotes meaning, then surely it must be the absence, after all we do notice what is not here as much as what is here. The intersections between the space and its occupants — the works, the audience — make visible the contestations of meanings and semantic impositions whilst still allowing for a degree of freedom in articulating a point-of-view not necessarily prescribe by the space or the curators.

⁷ Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Credit: Unsplash

⁸ Barcelona Pavilion

Credit: Unsplash

Credit: Unsplash

⁸ Barcelona Pavilion

Credit: Unsplash

This notion of intersections quite easily gave rise to that of the interstitial, something picked up by the Deconstructivists as canonised by the Museum of Modern Art in 1988, which showed the works of Coop Himmelb(l)au, Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Zaha M. Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, and Bernard Tschumi, the ‘starchitect’ septet of the period. The exhibition, eponymously titled Deconstructivist Architecture, induced a paradigm shift in the ways cities, their spaces, and memories of them, are construed; history could not be a closed-loop anymore, and neither could it play subaltern to the urban imagination. Instead, the Deconstructivists revisited the best of the modern thinkers and crystallised the precept that the museum experience, and the space made to tease it, facilitate it, could possibly be more important than simply hanging paintings and pointing to them.

Dynamism and movement trumped staticity, similar how potentiality trumped singularity.

The third of the Guggenheim museums, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao designed by Gehry, was, much like its New York predecessor, also a quasi-monumental statement that spoke to the possibilities of the built environment. Sited in the old industrial heart of the Spanish city, right next to the waterfront, the building’s airy atrium captured the light of Bilbao's estuary and its surrounding hills, and while the structure’s irregular form spoke of architectural articulations as spectacles, it is also an icon of the urban-scape that is unabashedly self-assured. One begins to feel hopeful, a little entranced — and given the perfect vision of hindsight, so did the city whose entire rejuvenation is arguably arbitrated by the construction of this hundred million dollar building.

The adoption of industrial materials and spaces, or former industrial spaces left behind by the hands of neoliberalism, to house museums also grew popular in the late 1990s, as land-use intensifies and urban rejuvenation schemes by municipal authorities come into full-force. Already wearing the patina of age, old factories, warehouses, and power stations repurposed as museums further emphasises Foucault’s styling of the museum as a heterotopia of time that brings to close proximity disparate objects from different times in a singular space, which attempts to encompass the totality of humanity’s temporal experience, by depositing additional layers of meaning and contextual history onto their institutional identities. The Tate Modern, which sits on the shore of Thames with a certain unassuming muscularity, is one example of this new development in museum typology that subverts the acontextual leanings of the modernists and Deconstructivists, by occupying a structure already laden with social memories and pathos, but the nature of which is wholly removed from the objects it now houses. This juxtaposition of the swooping drama of the completely detached context of the museum building against the small, conscientious works inside of it brings to mind the rawness of the human desire to remember, to document, to archive alongside the refinements in thought that brought lives and existence to the scale of civilisations and empires — it is in this way that the flame of museological impulse is kept aglow through the ages, enormous at times, tiny by turn, but always a constant presence, warming with its ageless charm the core of humanity’s soul.

The museum is now the super-category for which the works within adds to the growing polyphonous narratives; there is no longer just one way.

Dynamism and movement trumped staticity, similar how potentiality trumped singularity.

The third of the Guggenheim museums, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao designed by Gehry, was, much like its New York predecessor, also a quasi-monumental statement that spoke to the possibilities of the built environment. Sited in the old industrial heart of the Spanish city, right next to the waterfront, the building’s airy atrium captured the light of Bilbao's estuary and its surrounding hills, and while the structure’s irregular form spoke of architectural articulations as spectacles, it is also an icon of the urban-scape that is unabashedly self-assured. One begins to feel hopeful, a little entranced — and given the perfect vision of hindsight, so did the city whose entire rejuvenation is arguably arbitrated by the construction of this hundred million dollar building.

The adoption of industrial materials and spaces, or former industrial spaces left behind by the hands of neoliberalism, to house museums also grew popular in the late 1990s, as land-use intensifies and urban rejuvenation schemes by municipal authorities come into full-force. Already wearing the patina of age, old factories, warehouses, and power stations repurposed as museums further emphasises Foucault’s styling of the museum as a heterotopia of time that brings to close proximity disparate objects from different times in a singular space, which attempts to encompass the totality of humanity’s temporal experience, by depositing additional layers of meaning and contextual history onto their institutional identities. The Tate Modern, which sits on the shore of Thames with a certain unassuming muscularity, is one example of this new development in museum typology that subverts the acontextual leanings of the modernists and Deconstructivists, by occupying a structure already laden with social memories and pathos, but the nature of which is wholly removed from the objects it now houses. This juxtaposition of the swooping drama of the completely detached context of the museum building against the small, conscientious works inside of it brings to mind the rawness of the human desire to remember, to document, to archive alongside the refinements in thought that brought lives and existence to the scale of civilisations and empires — it is in this way that the flame of museological impulse is kept aglow through the ages, enormous at times, tiny by turn, but always a constant presence, warming with its ageless charm the core of humanity’s soul.

⁹ Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

Credit: Unsplash

¹⁰ Tate Modern Credit: Unsplash

Credit: Unsplash

¹⁰ Tate Modern Credit: Unsplash

II. NOTES ON SINGAPORE

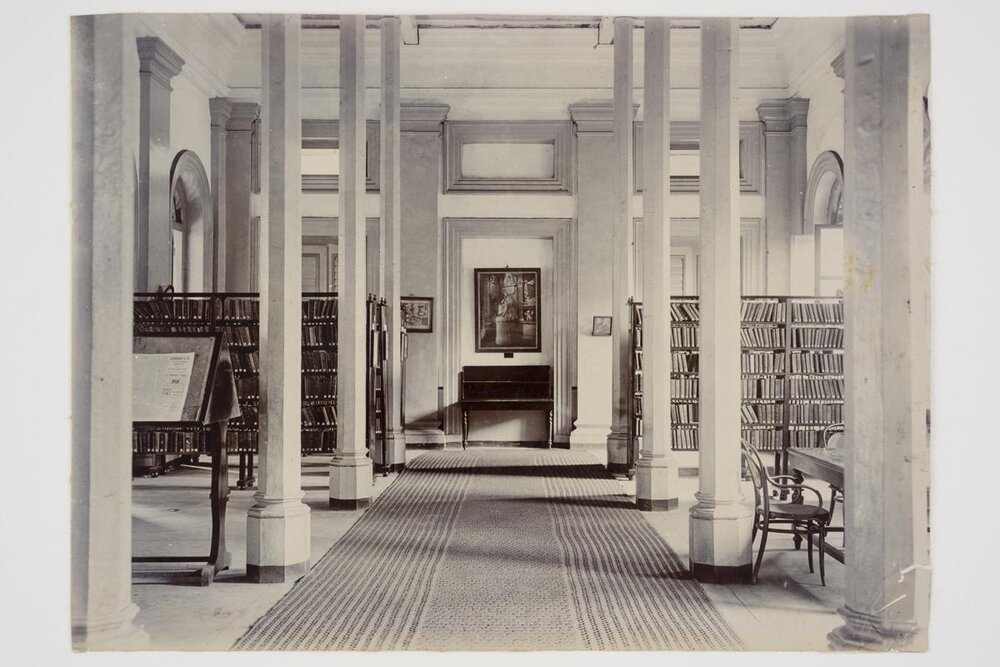

First, a brief account: The Raffles Museum, ostensibly the city-state’s first ever museum, was an initiative of the lauded colonial henchman founder of modern Singapore, Sir Stamford Raffles, which was finally founded in 1874 as the Raffles Library and Museum, before moving into its current structure in 1887. Meant to be the base for research and specimen-acquisition on both natural history and indigenous culture in the Malay Peninsula, the museum reflected the common colonial sentiment that knowledge was power. Designed by Sir Henry E. McCallum, the institution’s original structure, now the front block of the current museum, was stylistically Neo-Palladian, as was in vogue, featuring a symmetrical façade and pediments above its windows, alongside other Neoclassical architecture features such as Doric columns and pilasters on the ground floor and Ionic pilasters on the second.

Following Singapore’s attainment of self-governance in 1959, the museum lost its relevance and purpose as an extension of the colonial knowledge-creation organ, and was renamed the National Museum of Singapore (NMS) just a year later. After various administrative shuffles in the government, the museum would cede its natural history collection to other spaces and focus exclusively on the material culture of Singapore. The museum was not really active, and languished in a limbo of uncertain purpose for two decades before the state appointed a committee of senior officials and relevant stakeholders to re-examine the functions and potentials of the museum in the mid-1980s. The resultant research and report from the task force would eventually lead to a list of recommendations that were implemented in the 1990s: the museum was to consist of five separate galleries: one for fine arts, one for natural history of the region, one for local history, and so forth. This newly divided museum would be sited in a special museum precinct, and inform the character of the place — and in so doing, lift Singapore up and beyond its culture desert label.

¹¹ The Raffles Library and Museum

National Museum of Singapore, c. 1895

¹² The Library at the Raffles Library and Museum

National Museum of Singapore, c. 1910

National Museum of Singapore, c. 1895

¹² The Library at the Raffles Library and Museum

National Museum of Singapore, c. 1910

After the clarification on the scope of responsibilities for the National Museum of Singapore — briefly renamed the Singapore History Museum from 1993 to the spring of 2006 — four other national museums would be established in succession, the contemporary art facing Singapore Art Museum (SAM) in 1996, the ethno-historiographical Asian Civilisation Museum (ACM) in 1997, the ethnographic Peranakan Museum, itself a department of the ACM specialising in Peranakan culture which found institutional backing to be its own quasi-independent entity, and the art history writing National Gallery Singapore (NGS), which opened in 2015 following a decade long development period after plans were formally announced during the first Singapore Biennale in 2006.

Foreseeing a need for large scale coordination of the various cultural and heritage assets, the National Heritage Board (NHB) was formed in 1993, and the Museum Roundtable, a quasi-coalition of cultural organisation banding together for apparent solidarity, was formed in 1996. Precipitated by the cultural-planning Renaissance City Masterplans, the number of museological organisation mushroomed with much aplomb in the following years possibly due to the development of two prevailing notions of the public functions of a museum on the state radar: the first was the realisation that museums constitutes a promising segment of the cultural economy, and thus require more coordinated stewardship and development in order to achieve its optimum performance; the second was that museums serve as key markers of cultural development, and thus a symbol of cultural capital and quality of life.

In light of this neoliberal instrumentalisation of the museological interest of the state, it is interesting to thus note the ways that the architecture of the Singapore museum are informed by this general principle, and the methods by which the power dynamics of the (neo)colonial impulse are replicated through the containment of cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic objects in building that crystallises so clearly the colonial agenda of intellectual dominion.

The five national museological institutions of Singapore — the National Museum of Singapore, Singapore Art Museum, Asian Civilisations Museum, Peranakan Museum, and National Gallery Singapore — are all without fail housed in conserved structures designated as National Monuments under the stewardship of the NHB. In the case of the National Museum, the architecture had been built for the purpose of housing the imminent museum, while for the others their buildings feature the adaptive reuse of former educational institutions and civic buildings. Commonly built in one or another European architectural vernacular, most of the key civic institutions under British colonial rule are built in the Palladian, Renaissance, or Neoclassical style. Similarly, the buildings erected by major European enterprises that had the capital to build what they want also frequently adopted these styles. Though one may find a somewhat eclectic blend of architectural elements of both European and non-European origins in many buildings, it is often the case —with the possible exception of shophouses — that the European elements are what dominate the structural compositions of these buildings. The combination of this with the aggressive conservation policy by the state urban planner meant that whenever one considers heritages of the built environment, it is these colonial buildings which come to mind — a rather dramatic twist considering the strident anti-colonial efforts that the ruling party had lead while in the midst of consolidating their political power and voter base.

Foreseeing a need for large scale coordination of the various cultural and heritage assets, the National Heritage Board (NHB) was formed in 1993, and the Museum Roundtable, a quasi-coalition of cultural organisation banding together for apparent solidarity, was formed in 1996. Precipitated by the cultural-planning Renaissance City Masterplans, the number of museological organisation mushroomed with much aplomb in the following years possibly due to the development of two prevailing notions of the public functions of a museum on the state radar: the first was the realisation that museums constitutes a promising segment of the cultural economy, and thus require more coordinated stewardship and development in order to achieve its optimum performance; the second was that museums serve as key markers of cultural development, and thus a symbol of cultural capital and quality of life.

In light of this neoliberal instrumentalisation of the museological interest of the state, it is interesting to thus note the ways that the architecture of the Singapore museum are informed by this general principle, and the methods by which the power dynamics of the (neo)colonial impulse are replicated through the containment of cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic objects in building that crystallises so clearly the colonial agenda of intellectual dominion.

The five national museological institutions of Singapore — the National Museum of Singapore, Singapore Art Museum, Asian Civilisations Museum, Peranakan Museum, and National Gallery Singapore — are all without fail housed in conserved structures designated as National Monuments under the stewardship of the NHB. In the case of the National Museum, the architecture had been built for the purpose of housing the imminent museum, while for the others their buildings feature the adaptive reuse of former educational institutions and civic buildings. Commonly built in one or another European architectural vernacular, most of the key civic institutions under British colonial rule are built in the Palladian, Renaissance, or Neoclassical style. Similarly, the buildings erected by major European enterprises that had the capital to build what they want also frequently adopted these styles. Though one may find a somewhat eclectic blend of architectural elements of both European and non-European origins in many buildings, it is often the case —with the possible exception of shophouses — that the European elements are what dominate the structural compositions of these buildings. The combination of this with the aggressive conservation policy by the state urban planner meant that whenever one considers heritages of the built environment, it is these colonial buildings which come to mind — a rather dramatic twist considering the strident anti-colonial efforts that the ruling party had lead while in the midst of consolidating their political power and voter base.

¹³ National Museum Singapore

Credit: Unsplash

¹⁴ Peranakan Museum Credit: Unsplash

¹⁴ Peranakan Museum Credit: Unsplash

The adoption of colonial architecture by museums has also lead to the ossification of the association of an acontextual colonial aesthetic with historical legitimacy and socio-cultural capital; a decision that may or may not be consciously advanced by the shrewd economic calculations of the state apparatus which identifies a key segment of potential big-ticket investors to be from the former colonial empires. While the irony that colonial architecture houses and represents the gateways to indigenous knowledge and regional histories riddled with colonial trauma that have yet to be properly healed goes without saying, but it is also strategic in aligning an exceptionalist narrative of Singapore’s colonial experience with a world economic order dominated by Western powers, and furthers the notion that Singapore’s success comes from compliance with a colonial power structure that rewards far too fewer than what it punishes. When viewed against the post-war developmental history of Southeast Asia, this gesture also hints less than subtly that Singapore has taken the place of the colonial master — a wry refrain from an Indonesian artist who visited the National Gallery Singapore soon after its opening reveals this sardonic, if resigned, gem: “To see the best Indonesian art, visit Singapore” — and should thus assume the political, if not then cultural, leadership of the region.

What does it mean to be a museum? And beyond this: what does it mean to be a museum in Singapore? Aside from trying to bring to bear the necessity of a rigorous decolonial exercise in institutions stuffed to the brim with inertia, this is also the question that haunts not just the discursive space that museums occupy but also the physical — we can note that even the historicity of our historical monuments are questionable, because they were themselves stylistic mongrels of an imagined golden past. In the realm of definitions, the current debate rages: the International Council of Museums (ICOM) has put forth the resolution to change the definition of a museum from being “a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment” to being “democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures” that “acknowledg[e] and address[] the conflicts and challenges of the present,” “hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people” and “participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.” The fact that the stand for equity and social justice in the most fundamental aspect — creation and preservation of memory and knowledge — could still face opprobrium speaks volume about the current state of society.

Looking beyond the skins of the museum architecture into the architecture of power, one gets a sense that Singapore has not quite yet learnt the lesson of the colonisers who have with their own petard be hoist through imperial hubris and an insatiable hunger. Remaining imprisoned in the colonial state of mind, made tangible by the false old monuments, and presenting to the rich like a wayward catamite, toying with the capitalist imagination that makes empty promises, Singapore’s museums are at a point where a complete overhauling of its character — curatorial, architectural — is important now more than ever to really anchor a society to its shifting past. The writings are on the wall.

What does it mean to be a museum? And beyond this: what does it mean to be a museum in Singapore? Aside from trying to bring to bear the necessity of a rigorous decolonial exercise in institutions stuffed to the brim with inertia, this is also the question that haunts not just the discursive space that museums occupy but also the physical — we can note that even the historicity of our historical monuments are questionable, because they were themselves stylistic mongrels of an imagined golden past. In the realm of definitions, the current debate rages: the International Council of Museums (ICOM) has put forth the resolution to change the definition of a museum from being “a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment” to being “democratising, inclusive and polyphonic spaces for critical dialogue about the pasts and the futures” that “acknowledg[e] and address[] the conflicts and challenges of the present,” “hold artefacts and specimens in trust for society, safeguard diverse memories for future generations and guarantee equal rights and equal access to heritage for all people” and “participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world, aiming to contribute to human dignity and social justice, global equality and planetary wellbeing.” The fact that the stand for equity and social justice in the most fundamental aspect — creation and preservation of memory and knowledge — could still face opprobrium speaks volume about the current state of society.

Looking beyond the skins of the museum architecture into the architecture of power, one gets a sense that Singapore has not quite yet learnt the lesson of the colonisers who have with their own petard be hoist through imperial hubris and an insatiable hunger. Remaining imprisoned in the colonial state of mind, made tangible by the false old monuments, and presenting to the rich like a wayward catamite, toying with the capitalist imagination that makes empty promises, Singapore’s museums are at a point where a complete overhauling of its character — curatorial, architectural — is important now more than ever to really anchor a society to its shifting past. The writings are on the wall.

¹⁵ National Gallery Singapore

Credit: Unsplash

¹⁶ Asian Civilisations Museum Credit: Shutterstock

¹⁶ Asian Civilisations Museum Credit: Shutterstock

“Looking beyond the skins of the museum architecture into the architecture of power, one gets a sense that Singapore has not quite yet learnt the lesson of the colonisers who have with their own petard be hoist through imperial hubris and an insatiable hunger.”