How do we search for books in libraries, and how do catalogues shape our experience of them? Should books be read as textual materials, or should we approach them as an art object? We spoke to Daniel Lowe, curator at the British Library, about the library’s extensive and ever-growing collection of printed Arabic materials.

Since 2015, Daniel Lowe has been responsible for the British Library’s printed Arabic collections, including books, newspapers, periodicals and ephemera. In addition, Daniel has an interest in the Arabic manuscript holdings of the British Library. His current work focuses on the history of Arabic print as reflected in the holdings of the British Library and the role of digital humanities in accessing and researching collections. He is also involved in outreach and engagement based on the British Library’s Middle East collections, including the Shubbak Literature Festival. Previously, he worked as an Arabic language specialist, cataloguing, researching and digitising India Office Records related to the Persian Gulf (1750-1950). In 2017, Daniel curated the exhibition Comics and Cartoon Art from the Arabic World at the British Library.

Since 2015, Daniel Lowe has been responsible for the British Library’s printed Arabic collections, including books, newspapers, periodicals and ephemera. In addition, Daniel has an interest in the Arabic manuscript holdings of the British Library. His current work focuses on the history of Arabic print as reflected in the holdings of the British Library and the role of digital humanities in accessing and researching collections. He is also involved in outreach and engagement based on the British Library’s Middle East collections, including the Shubbak Literature Festival. Previously, he worked as an Arabic language specialist, cataloguing, researching and digitising India Office Records related to the Persian Gulf (1750-1950). In 2017, Daniel curated the exhibition Comics and Cartoon Art from the Arabic World at the British Library.

¹ Illustration by Dianna Sa’ad

RECOGNISING THE GAPS

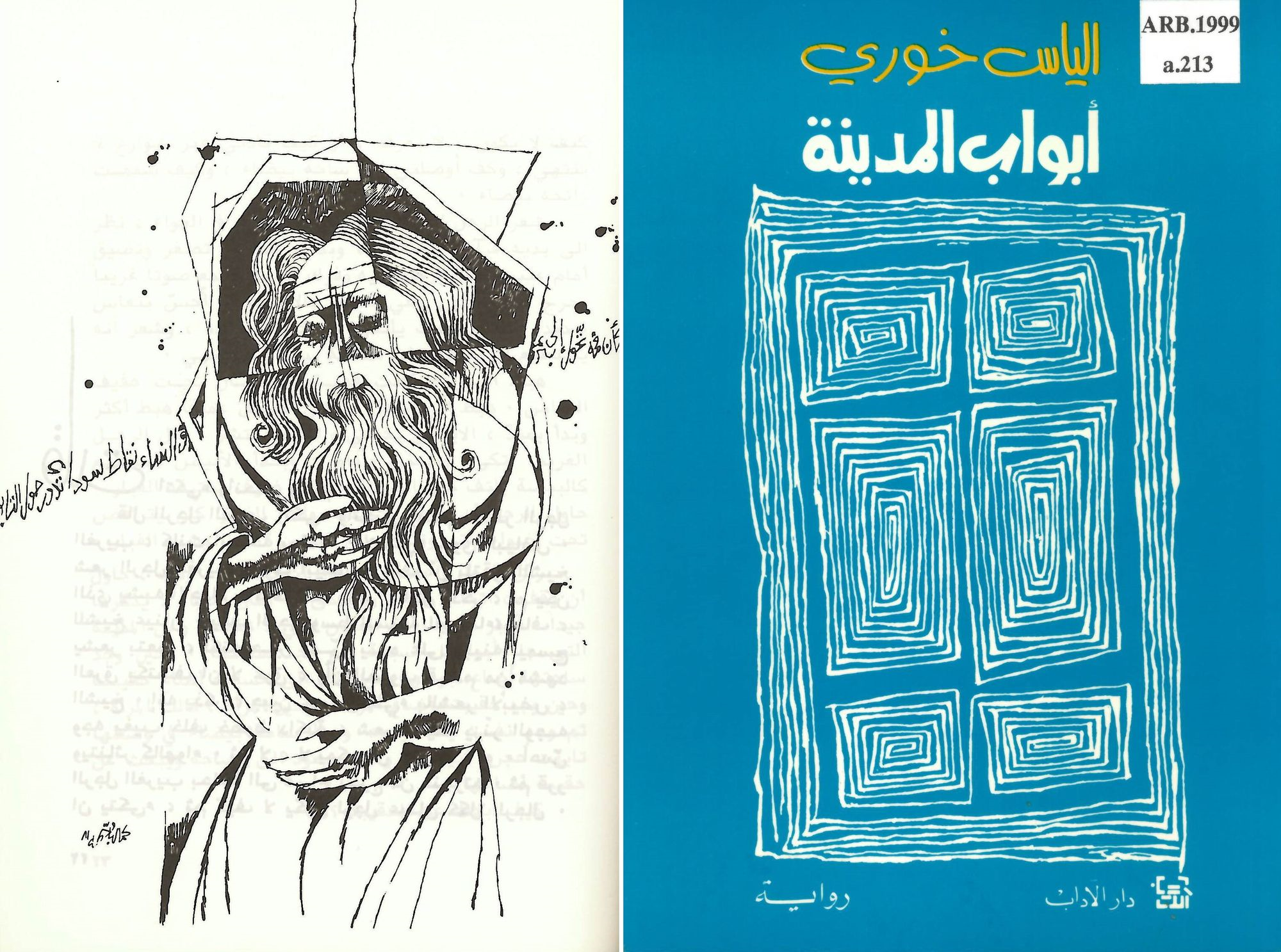

Daniel Lowe (DL): We have two books in the British Library collection that really got me thinking about how we catalogue books. The first is by the Syrian writer Zakaria Tamer, and the other is by the well-known Lebanese writer, Elias Khoury. Tamer is a prolific writer who lives just outside of Oxford, and Khoury was invited for a previous edition of Shubbak Festival. With these two events happening, I began to look up what we had in the collection so I could blog or tweet about it. When I called up these two books, their cover artworks immediately stood out to me. Yet in the catalogue entries, there was no mention of illustrators or designers. The cataloguing standards that we follow don’t necessarily require one to include details about cover art or internal illustrations. With أبواب المدينة (City Gates) by Elias Khoury, I realised that the cover art was done by Kamal Boullata, a Palestinian artist. I immediately added that into the catalogue records, because that is something worth noting.

It can often be quite difficult finding who the illustrator or designer for particular books were. With Arabic books, you can sometimes find this information within the publication details in the front. It could also be on the back cover or even the final pages of the book. Other times, you find the illustrations signed, which can sometimes be difficult to decipher as well.

Another example of this is the book by Zakaria Tamer, دمشق الحرائق (Damascus Fire). This book is illustrated by Dia Azzawi, another really well known Arab contemporary artist who is now based in London. These are artists who have exhibitions at institutions such as the Tate, and whose works are being sold at auction houses. Given that, such information should really be recorded in catalogues.

² أبواب المدينة : رواية (City Gates), Elias Khoury

British Library, ARB.1999.a.213, 1990

Cover Design and

Illustrations by Kamal Boullata

British Library, ARB.1999.a.213, 1990

Cover Design and

Illustrations by Kamal Boullata

³ دومة ود حامد (The Doum Tree of Wad Hamid), Tayeb Salih

British Library, 14570.d.57, 1969

Cover Illustrated by Mustafa al-Hallaj, Internal Illustrations by Ibrahim El Salahi

⁴ القتلى والمقاتلون والسكارى (The Dead, The Fighters and The Drunkards), Muin Bseiso

British Library, 14570.d.59, 1970

Cover Illustrated by Bahgat Osman

British Library, 14570.d.57, 1969

Cover Illustrated by Mustafa al-Hallaj, Internal Illustrations by Ibrahim El Salahi

⁴ القتلى والمقاتلون والسكارى (The Dead, The Fighters and The Drunkards), Muin Bseiso

British Library, 14570.d.59, 1970

Cover Illustrated by Bahgat Osman

PUBLISHING THE BOOK

DL: Dār al-ʿAwdah is a publisher in Beirut, Lebanon. In the 60’s and 70’s, they actively published the works of key Arab writers such as Tayeb Salih. When I called up Salih’s book, دومة ود حامد (The Doum Tree of Wad Hamid), I noticed that the cover art was done by Mustafa al-Hallaj. The book's internal illustrations were done by the Sudanese artist, Ibrahim El-Salahi. El-Salahi was the first African artist to have an exhibition at the Tate, and his work was recently exhibited at the Ashmolean Museum as well. The stories in Salih’s book reference Sudanese popular culture and the modernisation processes of the twentieth century. In his work, El-Salahi also references a lot of Sudanese spiritual lives and cultures. Having a visual element obviously adds another dimension to one’s reading experience, but political connections can sometimes be made between the artist and the writer as well.

I started notice a pattern here, and began to call up more books by the same publisher. They were publishing cutting-edge literature, particularly a lot of radical Palestinian poets, and worked with really great artists too. Another book by the same publisher is أغاني الدروب (Songs of the Byways), by the Palestinian poet Samih al-Qasim. This book’s cover was designed by the Egyptian artist, Bahgat Osman. Osman is well-known for his political illustrations and comic books. Interestingly, I’ve also been adding comic books to the collection so as to build it in a more visual way. Osman also did the cover for a book by Muin Bseiso, published by Dār al-ʿAwdah.

You often find that the artwork for books written by radical Palestinian authors were created by radical Palestinian artists. For example, Ismail Shammout did the cover for Ghassan Kanafani’s book, رجال في الشمس (Men In The Sun). This copy we have in our collection is the first edition, published in 1963 by Dār al-Ṭalīʿah, another radical publisher known for its socialist and communist material. This is a book that has been widely published and translated into many different languages since, so even then to go back to the first edition is interesting. What were they trying to package or purport by working with an artist such as Ismail Shammout? Through the books that we have in the British Library, I’ve been thinking about these connections between the artist, the writer, and the politics of the publishing houses. It would make for a really interesting avenue of research.

⁵ رجال في الشمس (Men In The Sun), Ghassan Kanafani

British Library, 14573.a.221, 1963

Cover Illustration by Ismail Shammout

British Library, 14573.a.221, 1963

Cover Illustration by Ismail Shammout

CATALOGUING AND RE-CATALOGUING THE BOOK

DL: When we catalogue, we seem to primarily see books as texts. As such, we make them available and discoverable as texts. That’s also how textual scholars and researchers will need to access these books, but it really got me thinking about books as objects and how art appears in them. As a library, we’re a repository of texts. Yet these books are also objects, so we are also a repository of objects.

If I wanted to survey all of the books and book covers we have in the Arabic Collection, one might think that all of the books are just stacked on top of a shelf. I could just take a spare day, come down to the basement, pick off a few books and head back to my desk to pore over an Excel sheet. However, these books aren’t actually stored on site here in London. We have mass storage up in Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, and these books have to be ordered in advance and take 48 hours to arrive. You can also only call up a limited number of books at a time, so it is both logistically difficult and time consuming to embark on a survey of these books.

As a library, our priority is also to make books durable. Books are sometimes taken apart, and in some cases, the covers are backed up onto a cardboard hardcover. However, the way in which these covers are sliced or bound back together can sometimes obscure important information about a book’s cover artist or designer. If a cover is sliced too far in, we sometimes lose artist signatures or aspects of the cover’s illustration. Other times, the cover is taken away entirely and replaced with a generic leather hardcover binding. We sometimes discard the book’s dust jackets, and many of these dust jackets ended up with the Victoria & Albert Museum. Again, this says a lot about how we, as an institution, did not see ourselves as a repository for visual material. We were getting rid of them and giving them away to an institution that was.

I often end up cross referencing the book we have to those in other institutions’ collections. As cataloguing traditions differ between institutions, you have catalogue entries from some collections in Germany or France that record book artists or designers. This also raises up interesting points about the amount of discretion each individual cataloguer has in recording information.

With Arabic books, we now include the title in both Latin and Arabic script in catalogue entries. Previously, we only had the transliterated Arabic titles reflected in these entries. There are various ways of transliterating Arabic, so there may be scholars using the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES) standard, but here, we use the Library of Congress standard. As such, a lot of my job includes explaining to people why they can’t find the things they are looking for.

⁶ النشيد الجسدي : قصائد مرسومة لتل الزعتر (The Body’s Anthem: Illustrated Poems For Tel El-Zaatar), Dia Azzawi

British Library, ORB.40/1081, 1980

Poetry by Mahmoud Darwish, Tahar Ben Jalloun and Yusef Saigh

British Library, ORB.40/1081, 1980

Poetry by Mahmoud Darwish, Tahar Ben Jalloun and Yusef Saigh

ARTISTS AND BOOKS

DL: As I said previously, many of the artists who were working on the cover art or internal illustrations for these books were accomplished artists in their own right. We’ve been acquiring artist books that are the result of a limited print run. For example, Dia Azzawi is really well known for his artist books. We have a book Azzawi illustrated titled مدن الملح (Cities of Salt). The text is by Abdel Rahman Munif, and it is a key modernist text on modernisation processes in the Gulf. On top of these projects, Azzawi also did illustrated story cycles for Al Amiloon fil Naft, which was the Iraq, Basrah and Mosul Petroleum Companies’ monthly magazine. Azzawi’s works are also filled with references to his heritage and history, and he worked with the Iraqi Ministry of Culture to produce a very didactic publication, ملابس الشعبية في العراق (Popular Clothing in Iraq). It’s always interesting to find these publications, because they show these well-loved artists and their works in a very different light. Yet, these books still relate very nicely to the symbolism and devices that these artists are known for.

With this process of trying to uncover what is absent or hidden, I began to realise that you could only search through the catalogue for the works of writers. Kamal Boullata, for example, was very much involved in the Palestinian publishing networks in the United States. Yet before I began to relook these catalogue entries, you wouldn’t have been able to search for books that had been illustrated or designed by him.

We have 100,000 printed books and periodicals in the Arabic Collection alone. It is a huge collection, by its nature, and it includes visually exciting material as well. Visitors or researchers might not immediately think of these books as art objects unless we categorise them as “artist books”.

⁷ مدن الملح (Cities of Salt), Dia Azzawi

British Library, ORB.30/8350, 1994

Text by Abdel Rahman Munif, Translated by Peter Theroux

British Library, ORB.30/8350, 1994

Text by Abdel Rahman Munif, Translated by Peter Theroux

CURATING THE BOOK

DL: Through my job of cataloguing and re-cataloguing books, I noticed the visuality and the art of the book. From a curatorial perspective, this sort of information is important for exhibition purposes. When putting on a retrospective on anyone of these artists, this knowledge would be of interest to curators.

Displaying books in a museum or gallery context is really difficult. Particularly as a library, we should be the ones who appreciate these books the most. I did a small exhibition of Arab comics and graphic novels back in 2017, Comics and Cartoon Art from the Arabic World. I wanted to look at comics in a historical sense, which is difficult when you consider our collecting practices. We tend to not collect books that are seen as being targeted at children, the reason being that these books might not have as much research value. Yet, I find comics and graphic novels to have great socio-political significance and aesthetic value. These books really lend themselves towards exhibition display. The vast majority of books we display are texts, but the audience’s perception really shifts when you bring in a visual aspect to that experience.

It felt strange and almost uncomfortable seeing these graphic novels behind display cases. I had been collecting these comics for a while, and I had been holding them, reading through them, and flipping through them. That personal experience of turning the page and seeing the next frame is especially important in comics. In that sense, I found it quite sad to then put these books behind glass. Of course I was happy to have put the exhibition together, but these books were never meant to be placed in cases. I’ve seen examples digital screens being used to allow audiences to flip through the book, even if the actual object itself lies within a case. But somehow, it’s still not the same from a tactile point of view.

It is also important for us to consider a book’s legibility when we display it. Palaeography is a skill, so even if the manuscript displayed is written in English, an everyday member of the public might still not be able to read it. We have to think about this and how we’re mediating this experience, because the audiences then become very dependent on what we as curators say the object is. Having a handwritten note transcribed in the form of a label is often helpful, and I think it is important to provide translations of materials written in other languages. These translations could be made available digitally so visitors could access them on their phones as they come into the exhibition. This is not really a huge step either. There are publishing houses that produce books that are trilingual — French, Arabic and English.

We sometimes overlook people who can’t read, audiences who don’t like to read, or audiences who find reading a traumatic experience. It is important that we find ways to provide access to those people, because the nature of this institution is that it prioritises the text. This isn’t to say that there aren’t texts at other arts institutions, but you could conceivably visit an exhibition at somewhere such as the Tate without reading any of the wall texts or labels. Sometimes the interpretation can even be a distraction from the object itself. In galleries such as the White Cube, the artwork’s title wouldn’t even be on the wall with it. You’d have to pick up a piece of paper from the front desk that outlines all the artworks in the space. When I step into these spaces, I do feel like I’m experiencing the work and the curation of the space itself instead of poring over texts.

⁸ شهادة الاطفال في زمن الحرب : رسوم اطفال الفلسطينين (In Time of War: Children Testify), Mona Saudi

British Library, ORB.30/8246, 1970

Designed by Vladimir Tamari

British Library, ORB.30/8246, 1970

Designed by Vladimir Tamari

FILLING THE GAPS

DL: With Arabic literature, it is important that we realise that demand and economics drive the sort of translations that are being done. Although this is not true of all Western readers, there seems to be a propensity for Western readers to want to read the Arab region through the lens of violence and political conflict. A simple exercise that would evidence this is to compare the covers of the original Arabic book with their translated counterparts. Often, the book covers of translations feature visual tropes of women in veils or minarets. There seems to be this inability to read with the text or the visual object for its own sake. Why are you reading a novel in order to understand a place? You would never do that with anything else. Doing a lot of this work led me to think — well, what don’t we have in our collection? I’ve now started to acquire around the themes of art in books, artist books, and things that speak more to the visual.

We acquired a book edited by the artist and sculptor Mona Saudi, which was published following the 1967 Naksa, which saw the further dispossession of the Palestinian people. As the West Bank was further occupied, more refugees were created. Saudi worked with refugees in camps, and helped them to understand their experiences of conflict through art. Art therapy is huge today and now receives quite a lot of funding from various NGOs all around the world. It’s really interesting to see a Palestinian woman and a Palestinian artist engage in this work so early on. The published book comprises of drawings done by and photographs of the refugee children. Her art isn’t really present, and her hand is more in the editing process, which is interesting to consider as well. This book really resonated with the radical politics of the time.

Another recent acquisition is Sufi Quotes by Samir Sayegh, who is a contemporary calligrapher. This is one of 400 copies, published by the Beirut-based Plan Bey. In this book, Sayegh worked with and calligraphed Sufi texts. This book resonates heavily with our collection’s historical roots in manuscripts and what is traditionally considered book art. We probably have the same text calligraphed in older manuscripts or albums in our collection, so to acquire something like this brings calligraphy into the 21st century.

Because we are a library, acquisitions are a huge part of what we do. We buy books, receive books through legal deposit, or through donation. In this way, we add at least 2,000 to 3,000 books to the Arabic Collection every year. I’m really conscious in acquiring new books that I’m not replicating this ethnographic gaze. To a certain extent, the library originated and continued on as an Orientalist collection for quite a while. The books were collected to support Orientalist studies. As a result, we have very specific gaps, and a part of what I’m doing now is to really shift that. Yes, we need to be collecting a lot of classical Arabic or Islamic edited texts, because that’s really important for our researchers. But I really want to look back at what we haven’t been collecting. Some of these books we didn’t collect when they were published, so it’s significant that we’re buying them now to fill those gaps.

When I first started my job at the British Library, I had this book by Mahmoud Darwish sitting on my table waiting for me. Ahmad Zaatar: A Poem was illustrated by Kamal Boullata, and published by the Free Palestine Press. We have multiple titles that feature poems by Mahmoud Darwish, so I made sure to reflect this information when cataloguing this unique title. On top of new acquisitions, it’s also a matter of recontextualising the books that we already have. There are things in our collection that do speak to a more nuanced or global perspective, but perhaps they might not have been catalogued in a way that brings those aspects out. You could include notes about details such as donor or artwork information to help readers to search through the catalogue more effectively.

⁹ Sufi Quotes, Samir Sayegh

British Library, 2016

¹⁰ Ahmad Zaatar: A Poem, Mahmoud Darwish

British Library, YP.2015.a.6638, 1970

Translated by Rana Kabbani, Illustrated by Kamal Boullata, Calligraphed by Elias Nicola

British Library, 2016

¹⁰ Ahmad Zaatar: A Poem, Mahmoud Darwish

British Library, YP.2015.a.6638, 1970

Translated by Rana Kabbani, Illustrated by Kamal Boullata, Calligraphed by Elias Nicola