Conversations in and around colonialism have heightened in Singapore amidst the Bicentennial — a commemorative series of events spearheaded by the government which marks two hundred years since Sir Stamford Raffles’ arrival. Whilst some countries worked hard to reclaim their histories in the post-independence period, piecing together thoughtful and critical perspectives towards pre-colonial and colonial histories remains an ongoing process in Singapore. Hot on the heels of these developments is a new exhibition at the National Museum of Singapore. An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819 throws the historical net wider by beginning the story in the 1600s — more than two hundred years prior to the date Raffles landed in Singapore.

Daniel Tham is Curatorial Lead at the National Museum of Singapore. He joined the museum as Assistant Curator in 2010, when he curated and set up in the following year the new Goh Seng Choo Gallery featuring the William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings. Specialising in paintings, prints and photography, Daniel has curated special exhibitions at the museum like A Changed World: Singapore Art 1950s–1970s, and was centrally involved in the revamp of the Singapore History Gallery in 2015. He is the curator of An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819.

Daniel Tham is Curatorial Lead at the National Museum of Singapore. He joined the museum as Assistant Curator in 2010, when he curated and set up in the following year the new Goh Seng Choo Gallery featuring the William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings. Specialising in paintings, prints and photography, Daniel has curated special exhibitions at the museum like A Changed World: Singapore Art 1950s–1970s, and was centrally involved in the revamp of the Singapore History Gallery in 2015. He is the curator of An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819.

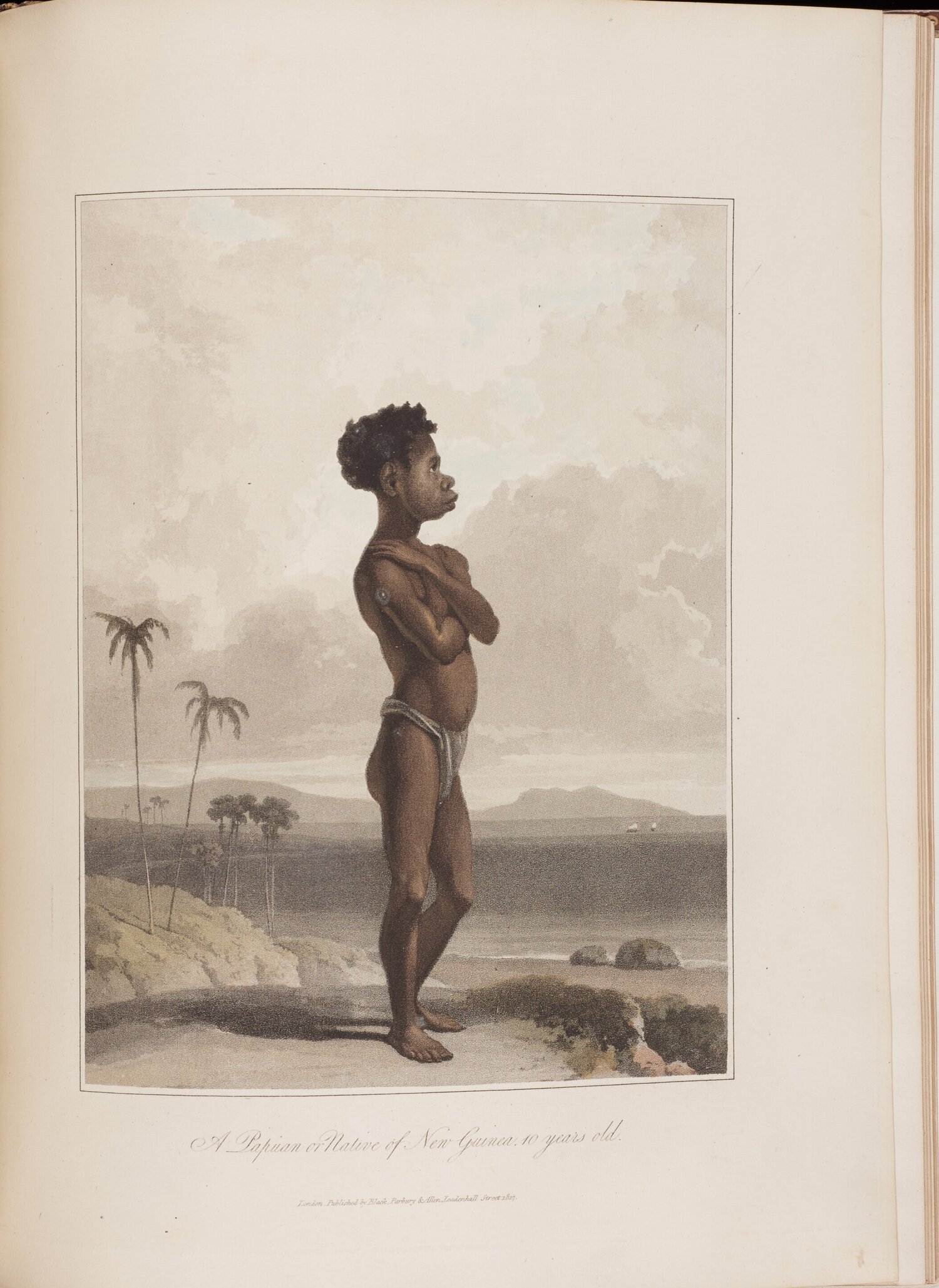

¹ A Papuan or Native of Java, 10 Years Old, William Daniell

National Museum of Singapore, 1817

Published in The History of Java (Volume 2)

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

² Native of Papua, Thomas Phillips

1817

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

National Museum of Singapore, 1817

Published in The History of Java (Volume 2)

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

² Native of Papua, Thomas Phillips

1817

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

TWO PERSPECTIVES OF THE SAME SITTER

Daniel Tham (DT): What you’re seeing here is a painting of a native boy from Papua. It is displayed next to a print that appears in Raffles’ The History of Java. The subject of these two works, a Papuan boy, found himself in the Balinese slave trade. We don’t know how he got there, but there is some suggestion that he was sold as a slave after being taken away from his family. There are some gaps there as to how Raffles, who was in Java at the time, managed to get this boy. Whether Raffles bought this boy as a slave, or purchased his freedom — we don’t know. Whatever it is, the boy ended up following Raffles from that point onwards. Interestingly, he accompanied Raffles on his trip to London in 1817. He became a sensation. Nobody had seen a Papuan before, and you can imagine the extent of this, particularly considering the nineteenth-century interest in physiognomy.

On one hand, there was this so-called scientific interest in this Papuan boy. Sir Everard Home, a surgeon and friend of Raffles’, took that opportunity to come and examine the boy. Following that examination, he proceeded to write a description that compared the boy to, what they called at that time, an “African negro”. What you see in the print, as reproduced in The History of Java, is meant to accompany the description written by Home. This print was done by William Daniell, who was well known for picturesque and romantic depictions of Asia. In the same way, this print presents a very objectified image of the Papuan boy. There is an emphasis on his jawline and even his buttocks.

I thought it was interesting to compare this print to the painting by Thomas Phillips. I was familiar with the print, but only encountered this painting when putting this exhibition together. We took this opportunity to get in touch with some of Raffles’ and Farquhar’s family members. We wanted to see if they might have anything in their collections that would be relevant for this show, and one of the family members had this painting. That really piqued my interest. I wondered if this could be the same boy. When I saw this painting, one of the first things that struck me was how large it was. It is extremely monumental in size. It was accompanied by a label that identifies the sitter as a Sumatran boy who was freed from slavery. The label was probably a later addition, and you don’t see it on display here at the museum. The painting’s artist, Thomas Phillips, was an interesting figure himself. He was a Royal Academician, a portraitist, and was extremely prolific as an artist. He painted more than seven hundred portraits throughout his career, and as far as I know, none of them featured a non-European sitter.

What threw me off was the fact that this boy was identified as a Sumatran. Going through the records, I couldn’t find anything that referenced a Sumatran boy accompanying Raffles on his expedition to London. It made me wonder if he could be the same boy in Daniell’s print. That led me to the National Portrait Gallery in London. They have a copy of Phillips’ handwritten notebook, and he recorded every person he painted throughout the years. In the page for 1817, there you have it. Phillips mentions painting a native of Papua. That really helped me gain confidence in two things. Firstly, it solidified the attribution of this painting to Thomas Phillips. At the same time, it also confirmed that the sitter in both the painting and the print were the same.

³ An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819

Installation View at the National Museum of Singapore

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

Installation View at the National Museum of Singapore

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

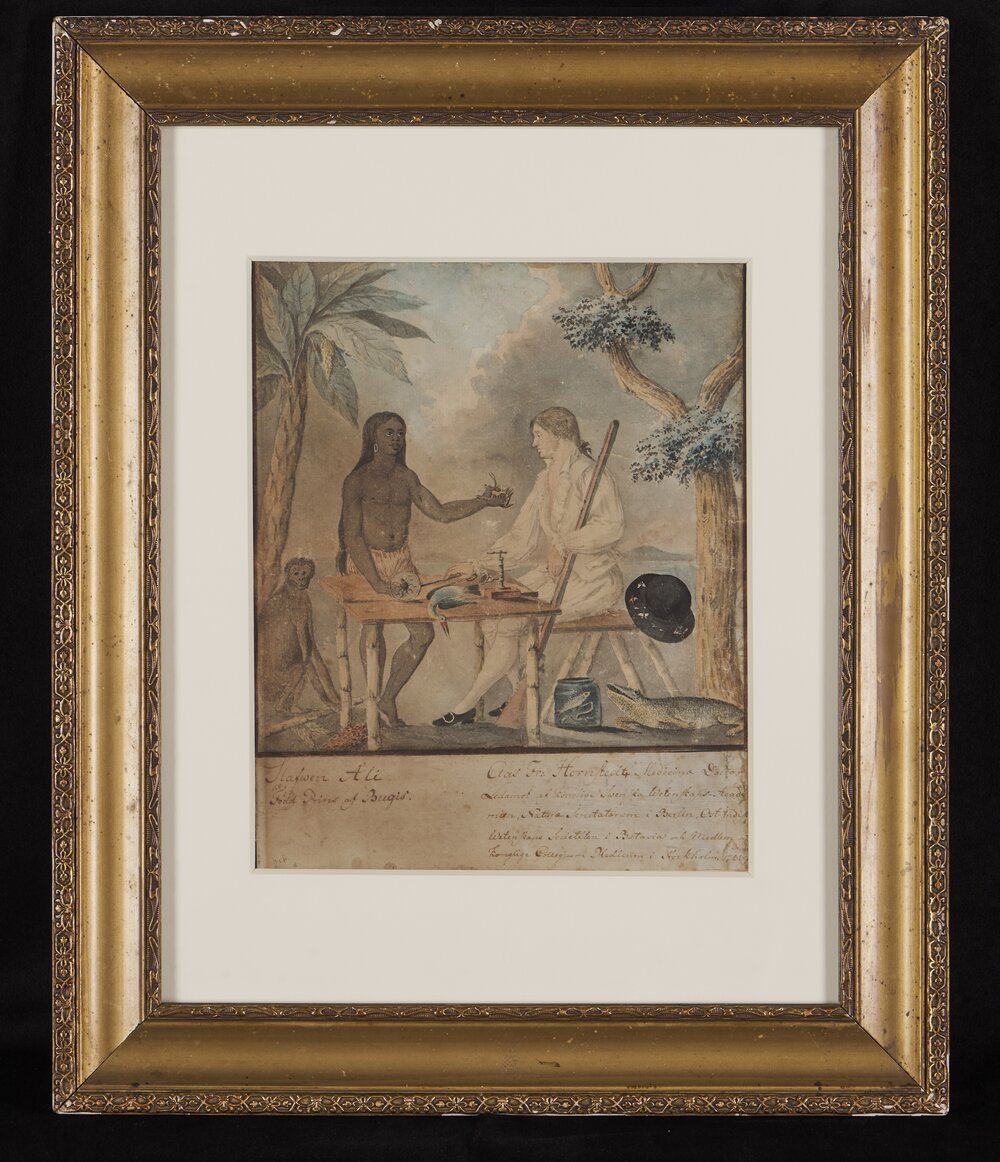

⁴ Claës Fredrik Hornstedt examining natural history specimens, attended by his slave Ali, in Java

National Museum of Singapore, 1788

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

National Museum of Singapore, 1788

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

WHO LIVES, WHO DIES, WHO TELLS YOUR STORY?

DT: Having these two images side by side offer a very interesting juxtaposition. It asks viewers to consider who this boy was. Evidently, he did not represent himself. Yet, you see a big difference even between these two images. This painting, in particular, is very different from all of the other artworks we have on display in this exhibition. It is placed within a zone we call ‘New Landscapes and Portraits’. Although we use a lot of visual materials throughout the exhibition to talk about this period of time, e wanted this portion of the exhibition to question why and how we use these materials in the first place. As a curator and as someone who’s trying to piece together what life in the East Indies was like then, what do I rely on as my source? Our own collections comprise of primarily European artworks and records. I constantly ask myself to critically examine how reliable or accurate these sources are. We’re caught in a bit of a bind, I think. On one hand, I think we can’t help but rely on these materials. This is especially in the absence of alternative sources. They are important, despite their imperfections, particularly in a period of time prior to photography. Yet at the same time, these works incorporate a very European imagination of the East.

If we were to restrict ourselves to the visual arts, or painting in particular, you do see how that necessarily is a lot more Western in its conception. Even if you do find locals representing themselves in those formats, more often than not, it is the result of them being educated in Europe or being influenced by Western ideas. Immediately, painters such as Raden Saleh come to mind. A lot of the local sources we consult are textual in nature. Having said that, it also depends on how much of a writing tradition in various communities. What we wanted to poke at through this exhibition was the production of knowledge. You see this expressed through two sections in the exhibition. The first section, ‘Shipping and Navigating in the Malay World’, looks at the mapping of our world. The other section, ‘Local and Scientific Knowledge’, look at this in relation to natural history. We wanted to see if we could establish the relationships shared between the Europeans and the locals, and the sort of knowledge that was produced as a result of that.

I want to talk about the Orang Laut for a bit, because we start off this exhibition with their stories. As a sea people, they are a group or community that have been marginalised in the presentation of Singaporean history. Their domain was the sea, and today we prioritise the land and territory. This is just one reason why they’ve been written out of history. I wanted to start this exhibition by looking at the role of the Orang Laut as sailors and as navigators. We have a couple of historical accounts that mention how the Orang Laut would be engaged as pilots or navigators to assist on European expeditions in our part of the world. It was their mastery of the seas around the straits that made these expeditions possible. I haven’t come across a single map that credits the Orang Laut for them, and that’s the sort of gap that we wanted to address.

There is one particular work we’ve shown that dialogues quite nicely with the painting and print of the Papuan boy. It is a print that depicts the Swedish naturalist Claës Fredrik Hornstedt, who arrived in Java in the 1780s. He did what most people did at the time — purchase a slave. This drawing shows Hornstedt examining specimens out in the field whilst being assisted by his slave, Ali. You see this relationship between the so called local and scientific depicted in one work. Although we don’t know much about the relationship between Hornstedt and Ali, it seemed that Hornstedt was quite fond of Ali. In the drawing, Ali hands a specimen over to Hornstedt. It begs the question of how much Hornstedt’s work required on local knowledge from people such as Ali. We don’t know the answer to this, but it is very much implied within the drawing itself. We know that knowledge, in scientific terms, greatly relied on local expertise.

You can go back to Raffles himself again for more examples of this. Munshi Abdullah tells us that Raffles had a whole contingent of local assistants that he sent out to collect different types of specimens. There was a very clear division of labour. In preparing for a descriptive catalogue on the birds of Sumatra, Raffles convened a committee of locals to advise him on the local names of these birds. He ends up reproducing these names in his catalogue, and this was published in the Linnaean tradition.

⁵ An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819

Installation View at the National Museum of Singapore

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

Installation View at the National Museum of Singapore

Credit: National Museum of Singapore

MUSEUMS, INSTITUTIONS AND THE SWELLING TIDE OF TIME

DT: One of the starting points for this exhibition was — so we know Raffles. But what kind of world did he come from, and what was the larger narrative or historical context around what happened in 1819? The Bicentennial looks at the two hundred years following Raffles’ arrival in 1819, so we thought it’d be fun to flip that backwards and consider the two hundred years prior to 1819. Having said that, we took the two hundred year framework really loosely because this exhibition starts from the 1600s. We wanted to use this exhibition to establish this bigger story, and to do so by examining different perspectives. We wanted to lengthen that narrative, and to broaden that geographical scope as well. You can’t talk about Singapore without talking about the broader region.

I think it is important for museums all around the world to look at the history of our own collections, especially in terms of where they have come from. On top of that, it is also important that we think about how we’ve been presenting these collections as well. The Museum of Modern Art in New York’s new expansion intends to relook art history as it has been presented. The museum has always been associated with a clear presentation of genres and movements in art history. They’ve done a good job of that, but with this expansion, they are working to include narratives and artists that were previously overlooked. In Amsterdam, the Amsterdam Museum has turned away from using the term “Dutch Golden Age” in all of its exhibits. That really reflects their sensitivity to perspective because whose golden age was it anyway? If you thought of it as a golden age for the Dutch, who suffered for that?

Coming back to the question of how the National Museum of Singapore does that, we’re pursuing this in several ways. The museum as an institution needs to remain relevant today. We do need to engage with the debates of the day. We can’t just exist in our own bubble, producing things within an unchanging framework. A lot of what we do responds to these discussions, and special exhibitions are great opportunities for that. I see this exhibition, in particular, as a way of opening dialogues. In putting it together, we’ve grappled with the imbalance in the availability of sources. Without shying away from showing these sources, we are very clear about our intention when we do show these materials. We’re conscious of how they were collected and what kinds of perspectives they purport. Coming back to the painting of the Papuan boy, the painting was not meant as an illustrative or indexical image. It is about the politics of representation, and this is the sort of approach we want to continue exploring in our future exhibitions as well.

Correction 03/12/19: This article misattributed the caption of the artwork by Thomas Philips as A Sumatran Boy Freed from Slavery by Sir Stamford Raffles. We regret the error.

An Old New World: From the East Indies to the Founding of Singapore, 1600s–1819 is now open.

The exhibition will run at the National Museum of Singapore until 29 March 2020.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

The exhibition will run at the National Museum of Singapore until 29 March 2020.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.