Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Psychogeographies

Issue: On Psychogeographies

Debbie Ding is a visual artist and technologist who researches and explores technologies of perception through personal investigations and experimentation. Prototyping is used as a conceptual strategy for artistic production, iteratively exploring potential dead-ends and breakthroughs–as they would be encountered by amateur archaeologists, citizen scientists, and machines programmed to perform roles of cultural craftsmanship–in the pursuit of knowledge.

Filed under: archaeology, found objects, installations, technology

¹ Ghost In The Shell, dir. by Mamoru Oshii

1995

Let’s begin our conversation with your work,

Wikicliki. The work is a motley collection of notes, receipts, and thoughts.

Take us through your process of scribbling, making notations, and processing

all of this information. How has your relationship to this habit changed over

time and as you’ve continued to develop your artistic practice?

When I made Wikicliki, it was meant to function almost as a notebook. At that point, I wasn’t working in art or in coding. Recently, I wrote an article for the National Gallery Singapore about productivity. With art making, there is always this drive to become productive, or to find personal ways of organising information. When I started Wikicliki, I had productivity in mind. I am quite obsessed with these productivity systems and have tried a number of them as well.

Parallel to the making of work, I’ve found the wiki to be a very good format for keeping notes. It has also helped me find ways to return to ideas, or to find the links between ideas. When I first started the wiki, I was a very big fan of the 1995 film, Ghost In The Shell. Featured in the film are these tachikomas that upload all of their knowledge onto the same server, and part of the story was that they were almost becoming sentient. The tachikomas were logging so many memories onto the server, but they didn’t know when the first instance of this happened. In a funny way, I felt like the wiki bears similarities to that in trying to log all my thoughts.

The wiki was something I started with colleagues when I was working in London. They slowly grew disinterested in the idea because maintaining a wiki is a lot of work, so I ended up doing it alone. This became my personal wiki over the years. Everything on there is public, even the notes of mine that are a little more personal. Having said that, the fact that there is such a mass of them makes me feel like there’s a bit of anonymity in the volume of it as well.

Parallel to the making of work, I’ve found the wiki to be a very good format for keeping notes. It has also helped me find ways to return to ideas, or to find the links between ideas.

I imagine that there must be a very detailed system to how all this content is managed on the backend. There is this spatial or physical element to this notetaking and collecting as well — both online, as with Wikicliki, and physically, as with The Substation Archive Exhibition. In some ways, this brings to mind something you brought up for our conversation as well — your encounter with sherds at the NUS Museum. What are some of the strategies or tools that have been definitive or generative in how you approach arranging, categorising, or visualising these fragmentary networks, webs, and systems of knowledge?

With the projects you’ve mentioned, it was always about finding ways to present the information all at once. What’s also interesting is that these are things that might have no relation to one another. Yet when you place them side by side, a strange juxtaposition can be created, and that might also transform all these different pieces of ordinary information. In thinking about the visual presentation of my wiki, the table on the homepage is quite important to me. With that, there are all these hyperlinks that you could click on as well. It’s also important to think about them in terms of proximity, where some ideas are closer to each other than others.

With the example of The Substation’s archives, they had so much material that they asked me to go through them as an artist. At first, I was quite uncomfortable doing it. I felt that the archives held content that was rather historical, but that was when they told me that their archives are already full of gaps. There are lapses in the documentation of entire years, for example, so it would have been very difficult to do an actual historical study of these materials. This was why The Substation thought of having an artist approach the archives instead. Ultimately, what they were interested in was the interpretation of the archives and its materials.

² Wikicliki (Home page), Debbie Ding

2008 -

³ Wikicliki (About), Debbie Ding

2008 -

2008 -

³ Wikicliki (About), Debbie Ding

2008 -

On that note, some of the projects you’ve done, such as The Library of Pulau Saigon and The Singapore River as a Psychogeographical Faultline, deal with the historical. As generative as archives are, some tend to fetishise it or its holdings, especially with materials that are either lost to the ether or difficult to otherwise access, and I’m sure this was something you were conscious of as well whilst working on various projects. Personally, how did you navigate the process of encountering, working with and through the archive?

When I was asked to do The Substation project, I thought of it as a memory palace as well. I tried to organise the materials by way of spaces. Somehow that made more sense than arranging everything along a linear timeline. I suppose I could have arranged my wiki in a linear format, but that would have created a very different project. I’ve thought a lot about tagging, categorising, and whether my categories were comprehensive enough. Over time, I’ve come to accept that interpretation is at the heart of my work.

When I was working on Here The River Lies, I tried to categorise all the cards I received. I received more than a thousand cards, and obviously any categories I made would have been incredibly subjective. As a designer, we do qualitative research by codifying everything that we’re working with so that we’re going through things formally and thoroughly. There’s a different between working with these materials as an academic researcher in history or the social sciences, and as an artist. In the case of Here The River Lies, I collected a lot of myths, stories, and memories.

There is no way of telling whether these stories are real or true, and that's the point. It wasn’t meant to function in the same way the standard memory project did. Over the past ten years, I’ve noticed quite a few memory project initiatives in Singapore. Most of them are focused on collecting or accumulating real memories. Categorising these memories with Here The River Lies adds another layer, or another filter, onto them. It makes it clear to people that everything they see presented is a translation, and that they will be doing their own translation in encountering these materials. Not everything should be taken as absolute truth.

There is no way of telling whether these stories are real or true, and that's the point. It wasn’t meant to function in the same way the standard memory project did.

⁴ Here The River Lies, Debbie Ding

2010, Installation View at Maison Salvan

⁵ Here The River Lies, Debbie Ding

2010, Installation View at the Singapore Art Museum

2010, Installation View at Maison Salvan

⁵ Here The River Lies, Debbie Ding

2010, Installation View at the Singapore Art Museum

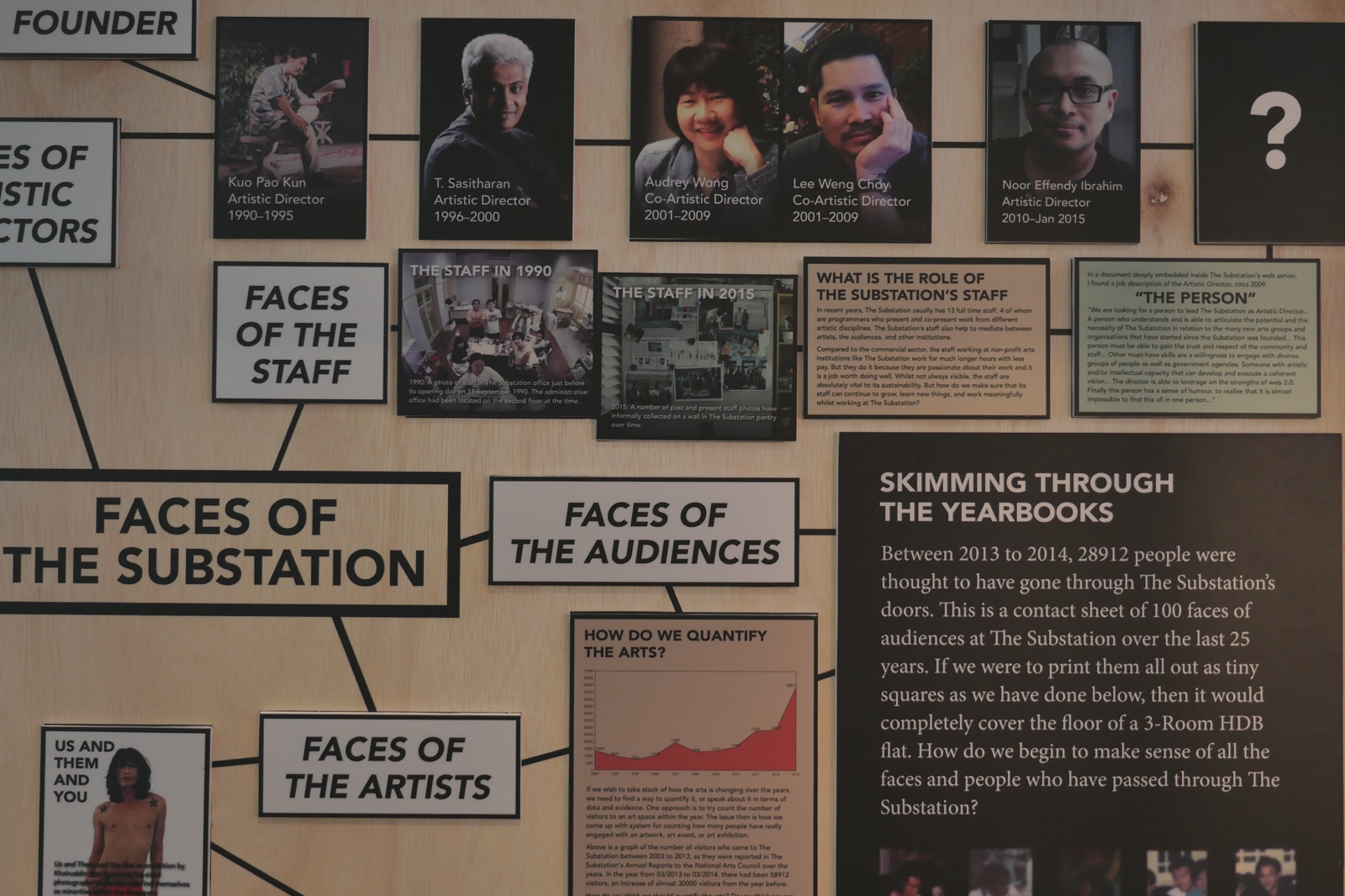

For our conversation, you pointed towards The Substation as a pivotal space for yourself — both as a space of development and connection. As someone who’s journeyed closely with the space for years, you worked on a piece that aggregated, collected, displayed and reimagined the archives of The Substation. Could you speak a little on that project, and how you would situate it now given the recent turn of events with the venue’s imminent closure?

It’s funny because I worked on The Substation’s archives in 2015. During that period, there was no artistic director appointed. The general manager had also left, and because there was no artistic director around to appoint a replacement, there was a huge void. It was very difficult for the staff working there at that point, and I had laboured under this sense of impending doom, so to speak. At that point, it wasn’t clear what the future of the institution would be and how it was going to sustain itself. People are raising questions now with regard to what the role of a board is, or who should be managing these institutions, but these were pertinent questions then as well.

When I was working with The Substation’s archives, I spoke to a lot of people, including artists who had shown things at The Substation over the years and staff who had been working there for awhile. I got the sense that quite a few of them had not thought so much about how one can sustain a practice over the years. I met a lot of people who no longer worked in the arts as well. These were people who had been very passionate and worked very hard on building up The Substation in its early years. They had now gone on to different places, and they decided that they no longer wanted to be archived or remembered in the same way. Ten years had passed since, and many of them were doing different things now. When I asked if I could write about them, I found it quite difficult to reconcile that. Some of these people were unsure if all their contributions should remain on the record. As some time had passed, some were unsure if they would historicise their participation the same way they did ten years ago. Over time, it almost seemed as if some wanted to reinterpret what happened in the past.

In a similar vein, it is important for me to be honest about the process of notetaking and to put everything online. It is clear to me that I might feel differently about it a couple of years on. I might not edit the note then, but I’ll probably add on to it so that I can see how my thinking around a particular topic has changed.

When speaking to some of the people who were involved with The Substation in its early years, how did you think through or handle personal stories that were coming through? This is considering the context that you were encountering these stories so many years on, thinking about how they could be situated, and managing that alongside your own artistic project.

Perhaps if you had a historian, who had to record the truth – or the truest account – of things, they would have encountered a dead end. It was evident that I couldn’t write about what happened in a single way. I’m not sure if it’s a good thing or a bad thing, but as an artist, I was able to treat these materials with a painterly stroke. I made mind maps that were rather voluminous, for example. If you go through all of them, there are points in which things are kept intentionally mysterious or vague. I could talk about myths and stories because this project was not meant to function as a historical account of The Substation. I was able to highlight certain materials and make other references.

Having said that, The Substation is a real place. It is an important place that perhaps also needs to be historicised by the right people. At the end of the day, I have mixed feelings about having been the artist that undertook this project. I wasn’t sure if I would represent The Substation faithfully enough. There were so many parts of the project that were incomplete or lost. There were songs, for example, written about the Substation that could no longer be found.

⁶ Making Space, Debbie Ding

2015, Installation View at the National Library Building

⁷ Making Space, Debbie Ding

2015, Installation View at the National Library Building

2015, Installation View at the National Library Building

⁷ Making Space, Debbie Ding

2015, Installation View at the National Library Building

Along with some of the projects we discussed

previously, I also wanted to come onto what I noticed is perhaps a sustained

interest in particular geological elements such as water bodies (the Singapore

River), soil, and rocks in your practice. What intrigue do these elements hold

for you? Do you see them as markers of space, historical continuums, vectors of

movement, all of the above, or something else altogether?

I have to say that I grew up in a very urban place and that the cities that I've since lived in are also very urban places. Perhaps in some way, this is me grasping at the fact that I don't necessarily have a very close connection with physical material and might find it very hard to access. Although I have explicitly made work about soil and rocks, I feel like I’ve almost made them so that I could have a reason to draw closer to that kind of material. I have been told that the work I’m doing comes across as a deconstructed landscape of sorts. I am quite interested in landscape drawings and landscape images, and dealing with material such as soil and rocks, was my way of trying to come to grips with the material directly.

Even when I was collecting rocks for the work Ethnographic Fragments from Central Singapore, the point of the project was that most – if not all – of these rocks were manmade. Even if you look at the Singapore River today, it's a canal that has been completely urbanised. I'm aware that most people would not be able to go into Singapore River and dig out rocks for themselves, so this sort of investigation remains the domain of a select few. By taking part in this, I’m trying to think of how I would approach the investigation as someone that has been alienated from geology itself.

I am quite interested in landscape drawings and landscape images, and dealing with material such as soil and rocks, was my way of trying to come to grips with the material directly.

Do you think of this work as, to some degree,

archaeological?

Definitely. When I was working on The Library of Pulau Saigon, I had the chance of coming into contact with Mr Koh Lian What. Mr Koh was the amateur archaeologist who was involved in the Pulau Saigon archaeological dig. He investigated the area out of a personal interest, and as I understand it, he was interested in Neolithic artefacts. This was all by coincidence. One of the interns who was working at the NUS Museum at the time was also helping me with my show. The intern had bumped into Mr Koh’s son, and that eventually led to introductions being made. What really fascinated me about Mr Koh was that he took a very artistic approach to his investigation. He made these little sketches of the artefacts he had found, and he often depicted the same object from different angles. It parallels, for me, the experience of looking at objects such as sherds. When I see sherds from archaeological digs at the NUS Museum, I’m turning them over in my mind.

In 2011, I was given the chance to show my work at the ArtScience Museum. As part of their blockbuster Titanic exhibition, they dedicated a small space to Singapore’s history. The works in this section dealt with what was happening at Singapore whilst the Titanic set sail on the other side of the world. My work about the Singapore River was on display there, and alongside it, there was a cabinet of original artefacts from the Pulau Saigon archaeological dig site. This could be an apocryphal story, but I recall seeing an object within the cabinet labelled as “label”. I don’t know what it was exactly, but it was a very small artefact. It excited me to see these objects, but a casual visitor encountering these objects would have been baffled. They would not have been able to make a coherent story out of what they were seeing. As an artist, I feel like I have the room to produce that story, or to produce something that would lead to that story being written or coming together. I feel like there is still a little bridge that needs to be made, and that's where art comes in.

⁸

The Library of Pulau Saigon, Debbie Ding

2015

⁹ The Library of Pulau Saigon, Debbie Ding

2015

2015

⁹ The Library of Pulau Saigon, Debbie Ding

2015

A recent work of yours, The Legend of Debbie,

is an incisive look into the concurrent and conflicting processes of

corruption, compression, enhancement, and duplication. At the same time, the

work offers up wormholes and portals for visitors to burrow into. In some way,

would you say that this project is an experimental extension of the network or

pathway quantification and visualisation that you’ve been engaged in even with

works such as Wikicliki?

All the works that I make, although they have individual arcs, always begin as writing. In fact, some of them begin as short stories that were totally fictional. In making visual works, my process is usually to think through them in stories and as fiction. The Legend of Debbie was a very literal version of turning a narrative into a journey. I think it's funny that I have never made film work or film narratives before. To me, games are an entry point into these things.

To this point, a lot of the things I've built and all the collections I’ve made might feel like a scattered collection. The viewer might feel like they still have to do some work in interpreting what they see. I’ve always wondered how one navigates the balance between simply leading the viewer along and directly narrating my version of the story to the viewer.

I am also interested in the fact that you’ve

described yourself as a visual artist and a technologist. I understand that the

digital has emerged as a necessary but salient strategy for your practice, and

I was wondering if you could expand on that thought a little. What do these

roles encapsulate for you, and how do they relate to one another?

For the past decade or so, I’ve always described myself that way. Perhaps the reason I add the word “technologist” into my profile is that it has been important for me to think also about the mode, or the medium, in which I present my work. When I say that I’m practicing – either as a fine artist or a visual artist – that element can sometimes be lost, that’s why I feel that it has been necessary to include that additional term. It also helps to frame how important it has been to my practice and approach.

I don't think I’ve approached art making in a traditional sense of going to art school, doing foundational courses, and thinking of work in terms of one, two, three or four dimensions. I never studied art formally and have always been making work in the digital. It was only recently that I told myself that it’d be really funny if I tried to use real paint. These things are funny to me, and I don’t know how it all works so I’m often trying to reverse engineer everything. When I see an effect, for example a glitch, I’m very mindful of what it represents in that physical medium. As an artist, one could perhaps be using the glitch just because it looks interesting. For me, however, I think that it is important to know what caused the glitch and why it happened. Filters in Adobe Photoshop too, for example, are a result of film and chemical processes. If I’m going to be using any of these effects, I need to know how they are formed, how they came about, and why I’m using it. The form has to complement the content as well.

If I’m going to be using any of these effects, I need to know how they are formed, how they came about, and why I’m using it. The form has to complement the content as well.

¹⁰ The Legend of Debbie, Debbie Ding

2021

¹¹ The Legend of Debbie, Debbie Ding

2021

2021

¹¹ The Legend of Debbie, Debbie Ding

2021

I think it was very intriguing for me to see

that you picked out Second Life for the conversation. Games, as you’ve said, are something that you’ve been exploring further in terms of how it can be a format

in which some works can be presented. They’ve always been an interesting

exercise in worldbuilding, and these possibilities are things that you’ve been

dabbling in with recent works such as VOID as well. Could you tell us a little

bit more about Second Life which you picked out, what you enjoy about the

gameplay, and how, perhaps, it has shifted or reconfigured your understanding

of space and dimensionality?

Second Life is something that I have never really made art in. I've enjoyed it over the years for the exploration it affords. If you’re stuck at home, but you want to go out, you can just go on Second Life. On the game, there is also no pressure to make art out of anything. There’s the Linden Endowment for the Arts, of course, a centre of arts activity on Second Life and where a lot of people are making interesting and strange art. The quality of the works there may vary vastly – some works seem stuck in the aesthetics and format of the 90s, and others are rather forward looking. All of this comes together on Second Life, along with pop ups that ask for donations, and the American Top 40 playing over the radio. I enjoy this mash up of things because it feels like a whole new world has been created. I also attended a Dorian Electra gig on Second Life recently, and that was quite funny. This was in the middle of the pandemic, and whilst you couldn’t go for live events in real life, you could participate in them on Second Life.

Over the past few years, I've been working on all the skills I need to build the world that I have in mind. It is still my dream to translate that world into reality. I tried doing that a few years ago, but I hadn't really reached the technical level necessary to sufficiently translate or express my ideas. I did a talk at the LASALLE College of the Arts recently, and we were talking about the importance of taking time to acquire or learn new skills in order to make work. When I look back at 2016, for example, I had no 3D modelling skills whatsoever then. It has taken years for me to learn things and to master them enough.

I’ve always thought of how spaces affect people and the way we behave. When you wake up from a dream, for example, and you remember what happened in it, that dream world can somehow colour the rest of your day. In a way, it can feel like you’re still stuck in that dream world. I’ve tried to translate this sensation into reality by way of drawing maps, because that has been the easiest way for me to record space. Maps, however, are two-dimensional. They don’t fully capture what I remember of the space. With Second Life, it sometimes feels like I’m entering a bit of someone’s dream and I’m filing away bits of information that I’ve seen on the game to help organise my thinking or my world.

Over the past few years, I've been working on all the skills I need to build the world that I have in mind. It is still my dream to translate that world into reality.

¹² VOID, Debbie Ding

2021, Installation View at Gillman Barracks

¹³ VOID, Debbie Ding

2021

2021, Installation View at Gillman Barracks

¹³ VOID, Debbie Ding

2021