Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Historicity

Filed under: archaeology, sculpture, installations, found objects

Issue: On Historicity

Filed under: archaeology, sculpture, installations, found objects

Fazleen Karlan's practice lies in the intersection of art-making and archaeological methods. She reassembles fragments of material from different time frames, constructing personal and cultural realities. Her interest includes examining patterns of erasure in landscapes. Fazleen has also participated in several group exhibitions in Singapor, and is a recipient of the Winston Oh Travel Award in 2016 and the Anugerah Cemerlang Mendaki (University) in 2019.

In a time fraught with questions surrounding the stewardship of our environment and how our histories have been told, artists have been embarking on meaningful meditations around our relationship to the land. For Fazleen Karlan, archaeology and archaeological methods have floated to the surface as poetic yet incisive methods for these inquiries. Trained as a fine artist but with professional experience as a post-excavation technician, Fazleen straddles the two disciplines of art and archaeology comfortably. This interview speaks to her ongoing interests in working with soil, found objects and fragments.

In a time fraught with questions surrounding the stewardship of our environment and how our histories have been told, artists have been embarking on meaningful meditations around our relationship to the land. For Fazleen Karlan, archaeology and archaeological methods have floated to the surface as poetic yet incisive methods for these inquiries. Trained as a fine artist but with professional experience as a post-excavation technician, Fazleen straddles the two disciplines of art and archaeology comfortably. This interview speaks to her ongoing interests in working with soil, found objects and fragments.

Let’s begin with the interview between Colin Renfrew, Ian Alden Russell and Andrew Cochrane. Published in Art and Archaeology: Collaborations, Conversations, Criticisms, the interview discusses artists who draw upon archaeological methods, something that your own work finds resonance with. Personally, do you see yourself as having a creative practice that encompasses your archaeological work, or an archaeological practice that encompasses your creative work?

Within my selection of artworks, I picked out an interview for this particular interview because this intersection isn’t something that's widely talked about in Singapore. In other countries, they've gone full on in trying to get artists and archaeologists to collaborate with one another. However in Singapore, the archaeological scene is comparatively smaller. Often, archaeological work is confined to the local university’s academic department. The department is small, and being a part of it myself, this became something I wanted to explore further. Coming back to your question around defining whether my practice is a creative or an archaeological one, I feel like it could be both at different times. It depends on when and where. It’s not always a 50/50 balance. Some days, I don't think about my creative practice or art making at all because my focus is on my work. There might be certain things that require my attention, or need to be done and expedited.

Having said that, I have a rather long commute to work. I have a lot of time on these commutes to zone out and go deep into my thoughts. It’s a time where I can think about new ideas. What would happen if I did this, or what would happen if I put those things together? That's how I usually go about my works. I wouldn't call myself an archaeologist because I'm not formally trained. I was trained as a fine artist. I would say that by having an archaeological aspect to my work,

it does influence the kind of practice that I have.

¹ #sgbyecentennial, Fazleen Karlan

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: Singapore Art Museum

² #sgbyecentennial, Fazleen Karlan

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: Singapore Art Museum

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: Singapore Art Museum

² #sgbyecentennial, Fazleen Karlan

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: Singapore Art Museum

Could you tell us a little more about how your relationship to your medium developed over time? How did your fascination with archaeology, historical fragments and shards begin?

I developed an interest in archaeology whilst doing my degree at the LASALLE College of the Arts. For my diploma graduation project, titled Stratum, I explored the Telok Blangah and Mount Faber areas, with a particular interest in the historical facets of that landscape that have been obscured. The area surrounding Telok Blangah was where Temenggong Abdul Rahman and his followers settled down after Raffles stripped him of his power. When you visit Telok Blangah today, all you will see are public housing flats, roads and overhead bridges. Much of this part of history has been erased from Telok Blangah, and I was intrigued by that.I was actually trained as a printmaker. I made a lot of silkscreen prints and ink drawings, which turned the present physical landscape into ghostly images. Compare this to how historical narratives have been turned into ghosts through the sanitisation of our physical landscapes. In Singapore, this happens all too often. We are a really small country, but a lot of our urban environment gets worked and reworked over and again. With Stratum, I wanted to question what we include and what we omit from our understanding of historical landscapes. This was the project that birthed my interests in archaeology, and I've been continuing with this work ever since.

As I was finishing up my degree, one of the things we had to complete was an internship module. I looked up organisations that work with historical materials, including museums and archives. Out of curiosity, I also wanted to see if there were people doing archaeological work in Singapore because it doesn't always get the press coverage it deserves. Eventually, I was able to secure an archaeological internship. This was how I got my introduction to shards.

On the first day of my internship, everything looked the same to me. I couldn't tell one shard apart from the other, and the sheer mass of it was quite intimidating. They were in the midst of processing 2.5 tonnes of artefacts from an archaeological dig site on Empress Place. I was starting from zero. I didn't have any archaeological knowledge, background or any practical experience out in the field. I just had an interest. I worked my way through slowly and started learning about what happens behind the scenes. It’s not just about excavating the artefacts from the ground. You also have post processing procedures, which tend to take a longer time to complete. This isn’t what we see represented on mass media, of course. When I tell people that I’m involved in archaeological work, they’d ask if my work involves digging for gold or dinosaur bones. That’s the kind of image that has been ingrained in most people, and it’s both fascinating and frustrating at the same time.

Singapore commemorated its Bicentennial last year, and that happened to coincide with the final year of my studies. There was a lot of discourse happening at the time around decolonizing our histories. We had been fed a particular narrative for the past 55 years. For most people, it was a sudden shift to now have the timeline shifted further back and be told that Singapore was more than 200 years old. I wanted to see what would happen if I put these two things together: my artistic practice, and the archaeological experience that I had. This was when my practice started moving away from printmaking and towards an object-based approach. I do miss printmaking sometimes, but it’s something that I can always come back to.

It also began to make more sense for me to work closely with soil. Soil is an important element in that it is central to any consideration around archaeology. Artefacts can only be uncovered when we remove layers of soil from the surface. At the same time, there are specialists out there who study soil itself as an object, and I found all of this very intriguing.

I made a lot of silkscreen prints and ink drawings, which turned the present physical landscape into ghostly images. Compare this to how historical narratives have been turned into ghosts through the sanitisation of our physical landscapes.

Let’s focus on something you said earlier about your initial encounter with shards and fragments, and how they can look very similar to one another. Apart from very cursory visual indicators such as colour or texture, it’d be very difficult for a someone with an untrained eye to read histories from these shards. As someone who now works as a post-excavation technician, how has your professional experience in processing artefacts from excavation sites affected how you handle materials within the context of your artistic practice?

Definitely. When you are involved in archaeological work, it's very tactile. Your hands are dusty all the time. You're touching things all the time just to figure out what in the world these things could be. Contrary to what some might think, art and archaeology do have their similarities. My current work relates to the post-excavation aspects of archaeology, which sits on the more technical side of things. It offers a different lens to look at objects: how we value objects, how we use them, and how we dispose of them. The objects that we readily discard will tell us more about ourselves than the objects we choose to keep. In a way, archaeology is a team sport. What I do professionally is a result of the labour that was put in by people who were here before me. It’s not a one man show. In this team, you have people who specialise in a lot of different areas. I'm not at the frontlines, I'm not always digging and I don't go to work looking like Lara Croft. That work has already been done by someone else. As a technician, my role is to take care of the artifacts right now for whoever is coming next. This means making sure that the artefacts are accounted for, cleaning them, and sorting them into the different categories or materials. We also do a lot of accessioning, where we attach serial numbers to all the artefacts that are big enough to be studied. This is all part of a process. Someone will then come along to conduct research on these artefacts, and their findings will be published in academic papers.

As an artist, I always approach a new project from a place of care. This is important to note, particularly in the context of Singapore, where we lose so much of our urban landscape to constant redevelopment and rejuvenation. Personally, I think my role as an artist is to map out the essences of these landscapes before we start to forget them.

The objects that we readily discard will tell us more about ourselves than the objects we choose to keep.

³ Stratum, Fazleen Karlan

2016

⁴ Stratum, Fazleen Karlan

2016

2016

⁴ Stratum, Fazleen Karlan

2016

Your works, Fractionated Automatic Sentiments 1-3, are part of an exhibition at Sullivan+Strumpf titled flat. As a result of the lockdown, or Circuit Breaker in Singapore, the works were also exhibited online — further flattening these works into the two-dimensional surface of a screen. How was the experience of making this work and seeing it exhibited on a digital platform like for you?

It

was very strange, yet exciting at the same time. I don't really keep up with technological advancements.

I'm trying to, but I'm a bit of a dinosaur myself. This whole idea of an online exhibition was very novel to me. The curator, Louis Ho, wanted the works exhibited to be as flat as possible — all the way down to the color schemes that we used, the medium itself, and how the works would look like in real life. I felt like this reflected the reality we were in and the sort of collective psyche we experienced at that time. When the online exhibition launched, it was surreal looking at my work through my laptop — especially knowing that I created it in three-dimensional form. With the navigation tools on the website, I could zoom in really close to see details on the work. It was as if I was holding the work in my hands. I could walk around the space and look at the other artists’ works — all without leaving my house. In spite of the restrictions on physical gatherings, such technology has allowed our creative practices to still persist. When it comes to the sort of possibilities that online exhibitions can afford us, I’m pretty hopeful.

Some would argue that works of art are always better in the flesh. You can really see the textures of an artwork when you view it in real life, for example. There’s definitely truth to that. When you experience something in real life, it draws you in in a different way. You get to soak in the energy of the room, or converse with the people around you. Having said that, this is the age we are moving towards and it's good to embrace it — one way or another.

Something that struck me whilst looking at them were the image-symbols you etched into the surface of these rock-like sculptures. It recalls, for me, the way in which we encounter Egyptian hieroglyphs. Of course, the images and symbols that your works reference are contemporary and resemble the way in which we use emojis today. Personally, do you use these symbols within your work as a reference to language or as a quasi-language in and of itself?

I was looking at Sumerian clay tablets, and how Sumerian cuneiform writing serves as a precursor to modern language — even predating Egyptian hieroglyphs. Cuneiform was one of the earliest systems of recording. The Sumerians used the materials around them for this, and clay was easily accessible. On these clay tablets, we can read about livestock, financial transactions, or taxation records. These are incredibly mundane matters, but these are still things that we can relate to today. Cuneiform takes the form of lines and marks, but it is a sophisticated communicative tool. By scratching onto surfaces, ancient writing became a very tangible and enduring record of what happened — although we’d probably need someone to translate the writings for us now. When you look at my work, the engraved markings hold very little information. They don't have specific colours or details, but you can still recognize them. This can be attributed to the psychological state that we are suspended in with the ongoing pandemic. In order to ascertain what these images are, the viewer has to draw associations between these symbols and objects familiar to one’s own daily life or routines. In working from home, watching Netflix, exercising, or communicating through Zoom, these little fragments are some of the things that you think back to in the course of encountering my works. Even everyday essentials, such as toilet paper or cleaning products, have become so much more precious. For some, these products can evoke a sense of reassurance that they can ride out this pandemic. This behavioral change, in a way, was something that I wanted to record in my work. I wanted to do this in a way that utilised the sort of language that we use today. The context of the pandemic influences the way in which we relate to these objects.

At the same time, the use of emojis now dominate our conversations. Let’s say you were speaking to your parents or an older relative as compared to your friends. If you were to use emojis in that conversation, your parents or that older relative might not always understand what you’re talking about. However if you text a friend the following emojis: 😔 😭, they’d somehow understand exactly what you mean. It has become a language that we now speak.

⁵ Fractionated Automatic Sentiments 3, Fazleen Karlan

2020, Installation View at Sullivan+Strumpf

⁶ Fractionated Automatic Sentiments 1-3, Fazleen Karlan

2020, Installation View at Sullivan+Strumpf

2020, Installation View at Sullivan+Strumpf

⁶ Fractionated Automatic Sentiments 1-3, Fazleen Karlan

2020, Installation View at Sullivan+Strumpf

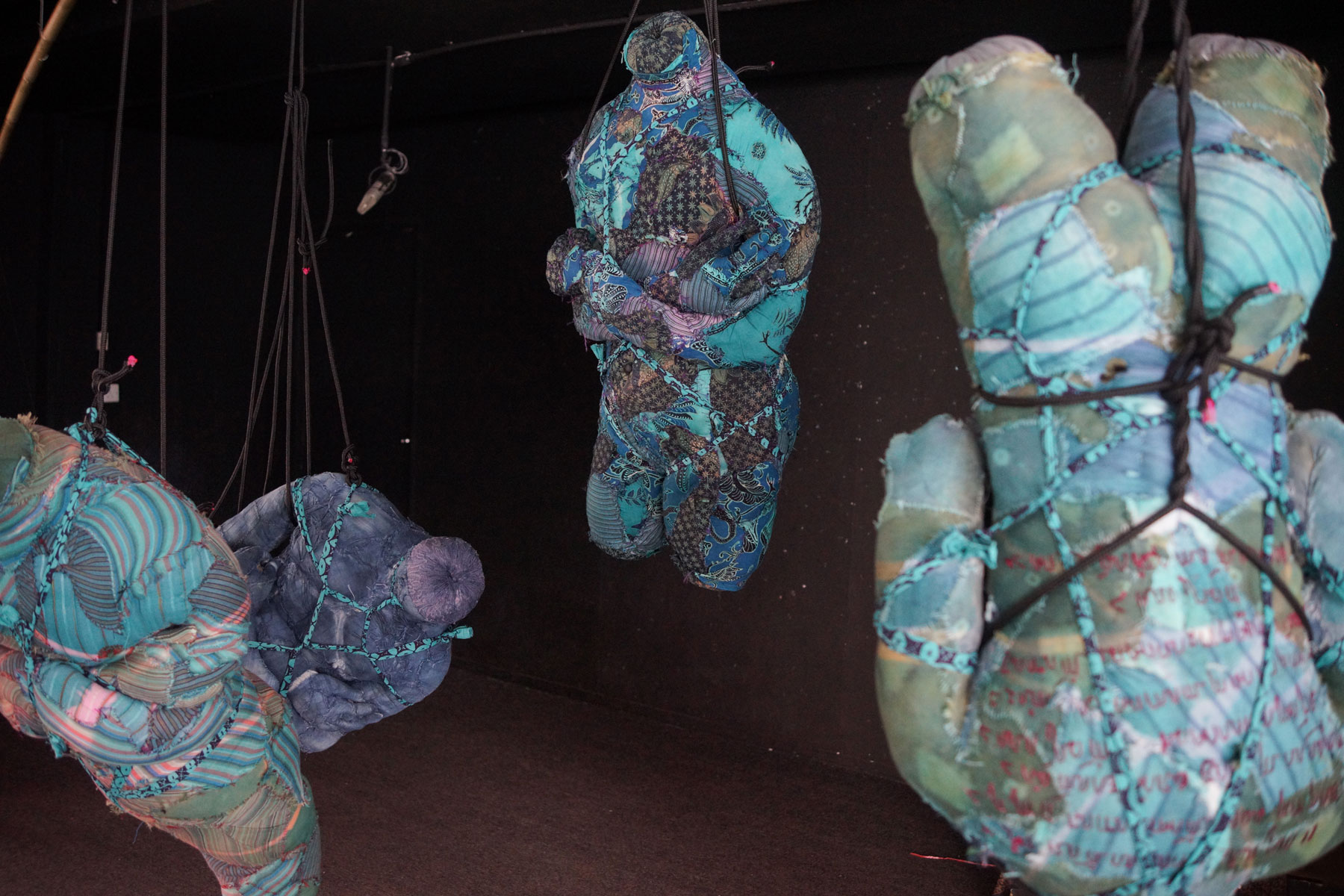

⁷ Seamstresses’ Raffleses, Jimmy Ong

2016, Installation View at OH! Emerald Hill

Another work you picked out for our conversation is Jimmy Ong’s Seamstresses’ Raffleses. The works resemble voodoo-dolls, and renders the usually authoritative figure of Stamford Raffles powerless. Tell us about the impact this work has had on you, and what you find compelling about the artist’s handling of colonial history and exploitative legacies.

For starters, it is a powerful work. Instead of using the original statue of Stamford Raffles that we’re all familiar with, Jimmy Ong and his assistants recreated the body of the statue. The treatment of the recreated body implies more about how history has been written than the original statue itself intended. When you build a statue, you are glorifying someone and you are coming very close to worshipping that person. When it is metaphorically removed from that pedestal and hung in chains, it really stands in contrast to the image the statue of Raffles portrays. It denies the glorification of Raffles as a figure and disrupts the stature that was granted to him. The way in which the recreated bodies were handled are also very voodoo-like, and in a way, it made me think of how we can exorcise the ghosts of our colonial past as they continue to haunt us. This work goes beyond just replicating historical material. On the dismembered bodies, text from The History of Java has been embroidered. This embroidery was done by Javanese woman, and it takes back or revokes Raffles’ status as a respectable source of knowledge. We tend to oversimplify parts of our history, and this is quite evident in how we’ve labelled Raffles as the founder of Singapore. This claim has since been refuted, especially in light of Raffles’ violent exploits. The artwork, for me, subverts this problematic representation of Raffles because it now provides the audiences with another lens to consider him. Instead of thinking of Raffles as someone who was brilliant and strategic, the work allows audiences to see Raffles as a perpetrator. Growing up in Singapore, that opportunity wasn't given to us. I’m not sure if this is a sentiment that people from the wider Southeast Asian region would be able to relate to, but it wasn't given to me. With this work, Jimmy Ong reclaimed what was taken away from us and that's something that I find very compelling.

In the work Seamstresses’ Raffleses, the techniques or methods that are used to exorcise these colonial ghosts are unique to both our local and wider regional contexts. Our colonial histories have often been presented to us as definitive, and arguably, we cannot use the same tools that our histories have been written with to critique those same histories. Is this something that you’ve come up within your practice? This is considering your position as someone who works with archaeological methods — which comes to us from Western traditions — to explore materials that might be unfamiliar to those same contexts — such as soil and fragments, which are centered around a deep knowledge of the land and its traditions.

In order to approach these questions in my practice, I need to address the sort of methods that have been used to study our histories and our landscapes.Archaeology itself, to put it crudely, is an area of study that can be characterised as being an outsider. You have archaeologists coming in from other countries and doing the archaeological work on local land. Inevitably, doing digs will destroy the site itself. Once you begin to excavate and dig into the land to get all the artefacts out, you can't have that same structure of soil ever again. It's quite destructive if you think about it from that perspective.

However, for me, it's about taking these methods and acknowledging our local histories and local knowledge. These local histories should also be elevated. What I try to do is to put two things together, even if they seem to contradict one another. When you place colonial histories alongside oral narratives, what do you get and how do you fill in those gaps?

What I try to do is to put two things together, even if they seem to contradict one another. When you place colonial histories alongside oral narratives, what do you get and how do you fill in the gaps?

⁸ Lambat Laun, Fazleen Karlan

2020

Credit: Danial Shafiq and Sufyan Haqim

⁹ Lambat Laun, Fazleen Karlan

2020

Credit: Danial Shafiq and Sufyan Haqim

2020

Credit: Danial Shafiq and Sufyan Haqim

⁹ Lambat Laun, Fazleen Karlan

2020

Credit: Danial Shafiq and Sufyan Haqim

Some of your previous works, including Lambat Laun and The Library of Physical Impossibilities, deal with materials and histories that we have lost over time. In working with historical artefacts or documents, the reality of the matter is that it will always be a race against the clock. How do you deal with or approach the factor of time within your work? Are you resigned to the fact that there will always be certain gaps in our understanding, continuing to resist or work against institutional amnesia or forgetting, or somewhere in between?

At this point in time, I definitely sit somewhere in between. My work deals with themes such as loss and time, and it’s about turning away from that resignation and learning from it. We will always be losing something — it’s inevitable and we won’t be able to save everything. Having said that, it’s okay to feel resigned. As an individual, one can only do so much. For me, the way in which I deal with this subject matter is to learn from the passing of time.You mentioned two of my works, Lambat Laun and The Library of Physical Impossibilities. The title of the work Lambat Laun comes from the Malay phrase that means “eventually”. When making this work, I kept thinking about this inevitability — that we’ll eventually lose a lot of our histories. I created the work knowing that it would be eventually destroyed. It was left out in the open, exposed to the sun and the rain. I stuck images to fabric sheets, but they weren’t adhered properly onto the surface. All of this was done deliberately as a nod towards the fact that there will always be gaps in our understanding. In this present moment, how do we care for what’s still here?

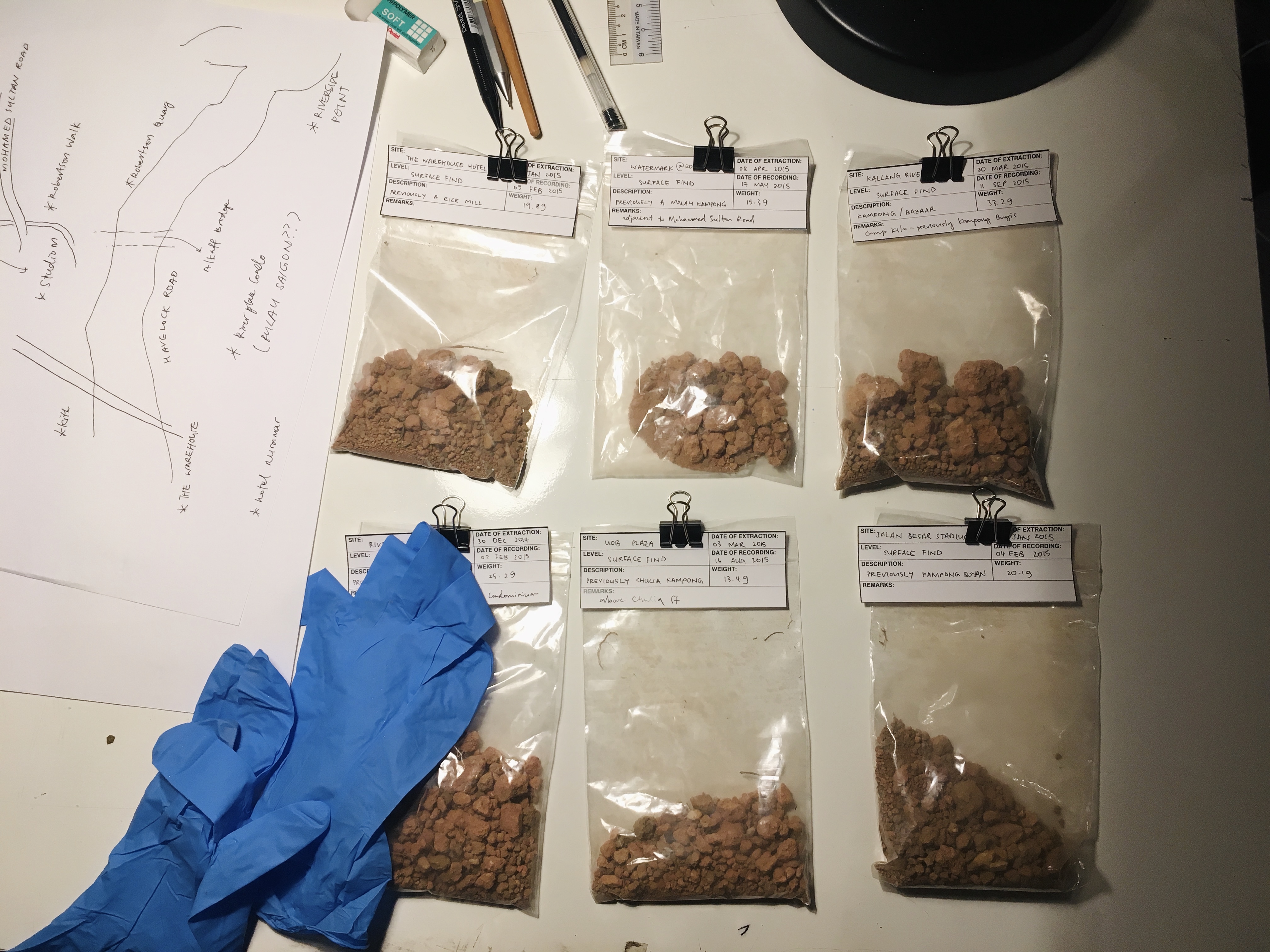

With The Library of Physical Impossibilities, I wanted to look at sites that we could no longer conduct archaeological digs on. This could be because the natural soil layers have been disturbed by construction. There are plenty of places in Singapore that fit this description, and this, to me, indicates a loss of information and knowledge that could have otherwise been extracted from the ground. That loss became the springboard for the work, and I wanted to document that sentiment of loss by collecting soil samples from the surface of these locations. These samples are arguably meaningless. When you collect samples from the soil surface, they are often mixed with rubbish, debris and rubble. It’s not going to give you accurate archaeological information. With the completion of the construction work, there is now no way we can access the site as it used to be. I wanted to examine how we can come to terms with loss. By using the language of archiving, documentation and labelling, does it hurt any less if we can put a name on it?

By using the language of archiving, documentation and labelling, does it hurt any less if we can put a name on it?

¹⁰ The Library of Physical Impossibilities, Fazleen Karlan

2019

¹¹ The Library of Physical Impossibilities, Fazleen Karlan

2019

2019

¹¹ The Library of Physical Impossibilities, Fazleen Karlan

2019

On that note of “useful” versus “useless” samples, archaeology is an academic discipline that comes with its own perimeters to dictate what can and cannot be done. In having an artistic practice alongside archaeological interests, do you feel that this lends a certain imagination or penchant for storytelling that perhaps the confines of archaeology as a discipline do not?

Despite its need for precision, I do think archaeology is capable of telling a story. There are certain techniques that experts use in order to determine dates, timelines and conditions. These skills come down to technical know-how, but I still think they help to string a story together. An artistic practice, however, adds on to all of this. It provides an imaginative or speculative element that allows for free play. I can play around with historical scenarios, but I’ll eventually hone into one particular scenario when conceptualising a work. I don’t see this as playing into a binaristic situation of good or bad or black and white. I see archaeology as setting the foundations for what I imagine in my own works.

¹² Memory Palace, Es Devlin

2019, Installation View at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery

To end our conversation, let’s discuss the final work you picked out — Es Devlin’s work, Memory Palace. The work took up an entire gallery space when it was presented at Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery, and warped the space around it to produce novel perspectives. When asked about what she wanted people to feel when they saw her artworks, Devlin said that, for starters, she wanted people to feel. Could you tell us about how your own encounter with Devlin’s Memory Palace made you feel? How did this experience shape the way in which you facilitate an audience’s emotional and physical encounter with your work?

My first encounter with Memory Palace was online, both through videos and reading about it. I was in awe. I kept replaying the videos over and over again. I wanted to see how the audiences interacted with the work, and by extension, the space around them. It really highlights the way we’ve changed — from civilisation to civilisation, and throughout time. It’s really something to marvel at. In your question, you mentioned Devlin wanting people to feel when they saw her works. I have to agree with her. In the context of Singapore, we’re constantly rushing towards newer or shinier things. For starters, it’d be great if people could feel more for the things we already have. If we dig into our own historical landscapes, we’d find an abundantly rich source of stories, narratives and lives. All it would take is a simple exercise in rummaging through our national archives. Our ancestors were once split across various islands. I know its a little hard to believe, but it happened. For all of us to now be squeezed onto a single island, I feel like we don’t have enough space to breathe, to feel and to think about what we feel. This is why I work towards recapturing that sense of wonder and curiosity within my art. This is also why having an archaeological element to my practice is really important. In time to come, I do hope that we’ll see more artists who consider archaeological elements in their practice. This comes down to a matter of resources of course, but I do hope that we’ll come to a point where we can direct more of our attention towards these areas of study.

Every time I choose my materials, I think about the entire space of the exhibition. What if people were to come in from both ways at the same time? What are they going to see? I’ve been told that from a distance, my work looks like fried chicken. It’s a hilarious response, but it’s a response. From there, I can engage them in conversation about the sort of materials that were used and that’s a dynamic that I really enjoy. Having said that, I can’t always be in the same space as my work all the time. A case in point would be my work, #sgbyecentennial. When it was exhibited at my graduation showcase, I left a couple of cotton gloves onsite to encourage viewers to interact with the work. I wanted them to pick it up and to look at it. Given the current concerns around Covid-19, this wasn’t something that I could replicate at its current iteration at the National Gallery Singapore.

I used to think that I could just leave work at a particular location and that’d be that. Over the years, however, it’s become increasingly clear to me that that’s not the case. It’s really about how I want people to feel, and how I’m going to facilitate that. Over time, my practice has become more sensitive to where my works will be exhibited and how the venue’s spatial histories will factor into the reception of my works.