Essays

from the 02/2019 Issue

Filed under: sculpture, painting, drawing, prints, manuscripts, installations

from the 02/2019 Issue

Filed under: sculpture, painting, drawing, prints, manuscripts, installations

Mythical creatures can be found in almost any culture around the world, and they can take on a variety of forms. Often, they also make reference to indigenous species of flora and fauna. When we think of mythical beings that bear resemblance to real life creatures, it becomes clear that some have emerged as prototypes for these processes. In particular, birds have been invented, reinvented, collaged, embellished and redefined across space and time.

Owing to the fact that birds can be found across all seven continents, they have featured as characters in fictional stories (Jemima Puddle-Duck or Kehaar in Watership Down), cartoons (Big Bird in Sesame Street or Bad Badtz-Maru by Sanrio) and movies (Iago in the animated Aladdin films). They also feature prominently in mythologies. These bird-like creatures often draw upon characteristics associated with birds, such as feathers, wings, beaks or talons. Within stories about these creatures, their characteristics or abilities are often highlighted or made obvious. Sculptures, drawings and paintings could be made in these creatures’ likenesses as well. These could have been used to illustrate stories, or as tools to further dramatise their telling. Through iconographies and representations, artists imbued mythical beings with physical shapes or forms, evidencing an indelible relationship between word and image.

![]()

Owing to the fact that birds can be found across all seven continents, they have featured as characters in fictional stories (Jemima Puddle-Duck or Kehaar in Watership Down), cartoons (Big Bird in Sesame Street or Bad Badtz-Maru by Sanrio) and movies (Iago in the animated Aladdin films). They also feature prominently in mythologies. These bird-like creatures often draw upon characteristics associated with birds, such as feathers, wings, beaks or talons. Within stories about these creatures, their characteristics or abilities are often highlighted or made obvious. Sculptures, drawings and paintings could be made in these creatures’ likenesses as well. These could have been used to illustrate stories, or as tools to further dramatise their telling. Through iconographies and representations, artists imbued mythical beings with physical shapes or forms, evidencing an indelible relationship between word and image.

SIMURGH

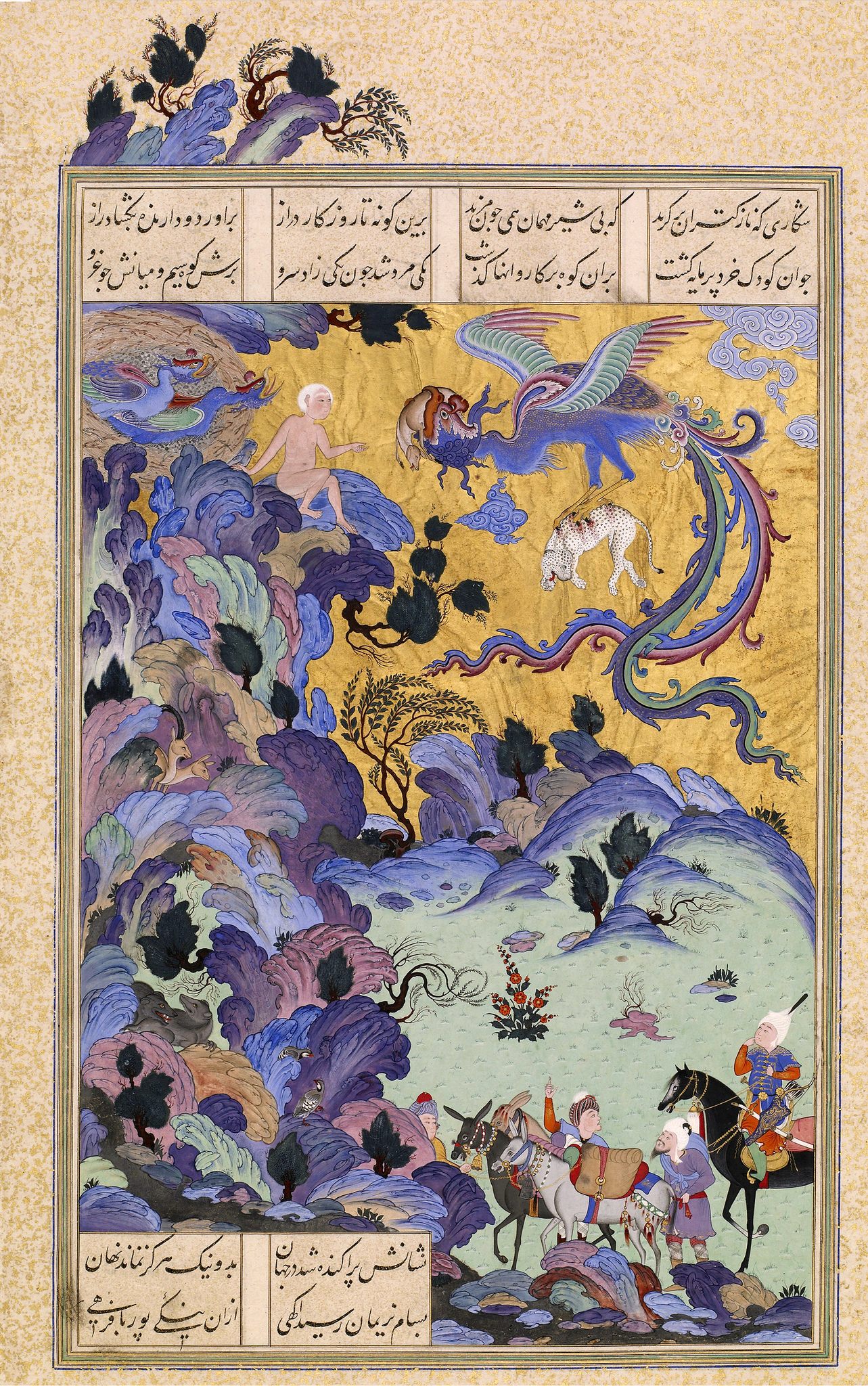

In Iranian literature, the simurgh (سیمرغ) is a mythical bird that features within poetry.1 Most notably, it features within the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) as the protector and guardian of Zal, a great warrior-king. Zal was born with white hair, and was abandoned in the Alborz Mountain as a baby because of this. The simurgh found the child, and took him in as her own. She cared for the young king until he caught the eye of a passing caravan. Before parting, the simurgh handed Zal three feathers from her tail, and promised to come to his rescue whenever he lit any of them. This story has been illustrated in many Shahnameh manuscripts, with the most prominent being the painting of the scene in the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp.

The simurgh also features in other important works of Persian literature. Written by Farid ud-Din Attar in the 12th century, The Conference of the Birds, is centered around a quest for the legendary Simurgh. Within Sufi mysticism, the simurgh is often used as a metaphor for God. As such, the quest outlined in The Conference of the Birds was really a search for divine presence and wisdom.2

¹ Zal is Sighted by a Caravan, attributed to Abdul Aziz

Freer Sackler Gallery, c. 1525

² The Simurgh Returning Zal To His Father, Page From A Shahnama Of Firdausi

Seattle Art Museum, c. 15th-16th century

Freer Sackler Gallery, c. 1525

² The Simurgh Returning Zal To His Father, Page From A Shahnama Of Firdausi

Seattle Art Museum, c. 15th-16th century

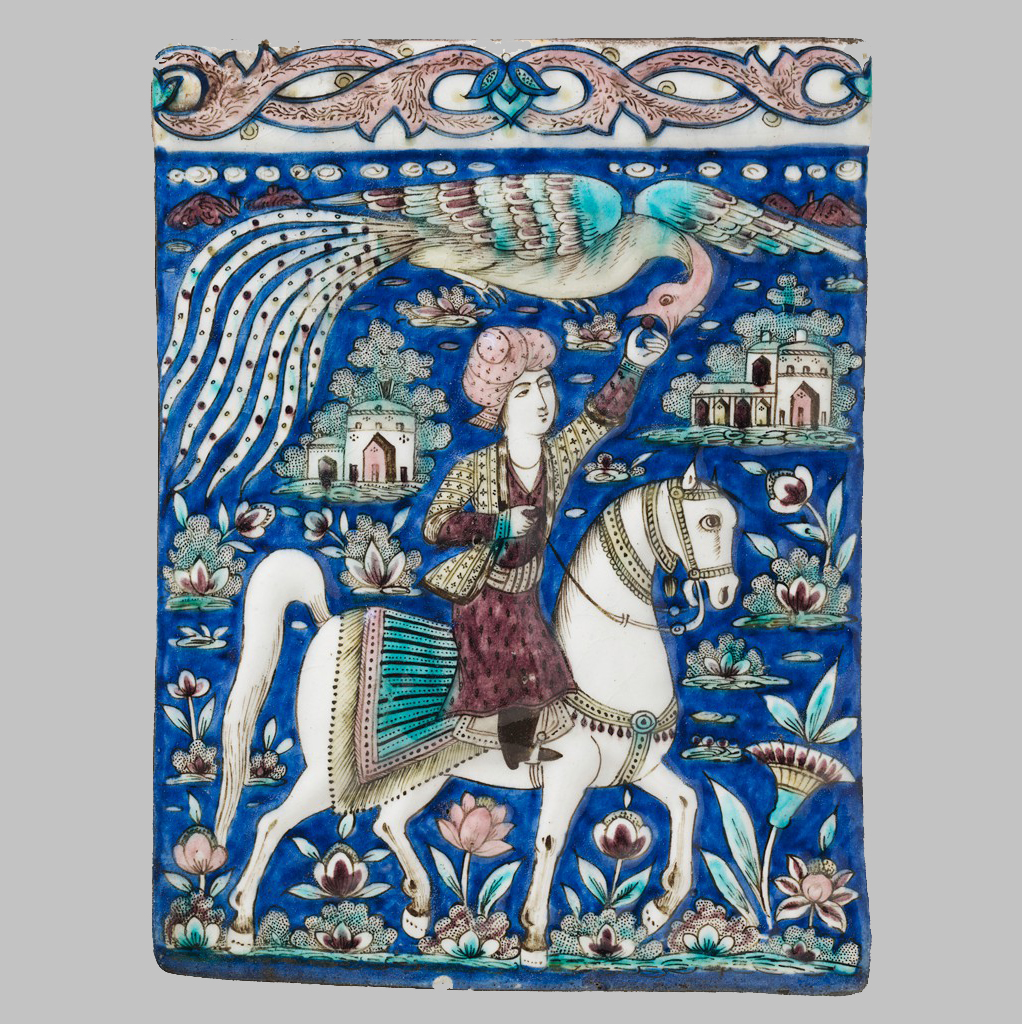

The simurgh is commonly depicted as a large, brightly coloured bird with magnificent tail feathers. The origins of the simurgh could have been in Zoroastrian religious texts. Mention is made in the Zoroastrian holy book, the Avesta, of a mythical bird called the senmurv.3

Depictions of the Persian simurgh are similar, in many ways, to the East Asian phoenix, or fenghuang. Both mythical birds are often portrayed with impressive plumage and their wings spread wide, mid-flight.

Depictions of the Persian simurgh are similar, in many ways, to the East Asian phoenix, or fenghuang. Both mythical birds are often portrayed with impressive plumage and their wings spread wide, mid-flight.

³ Tile with a Simurgh (Sechseckfliese mit Simurgh)

Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, c. 1270

⁴ Tile with Horseman Feeding Simurgh

Harvard Art Museums, c. 1860

Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, c. 1270

⁴ Tile with Horseman Feeding Simurgh

Harvard Art Museums, c. 1860

FENGHUANG

The East Asian phoenix, or Fenghuang (凤凰), is an auspicious symbol associated with virtues of benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and sincerity.4 Phoenixes were also often paired with another mythical creature, the dragon. The First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, proclaimed himself having descended from the dragon. This meant that the Empress was often associated with images of the phoenix, and phoenixes would often appear alongside dragons on imperial insignia. A phoenix sighting also bode well for the imperial court, as it was thought to symbolise a period of peace and security for the empire. The symbolism of the phoenix has shifted over time, but it has always been associated with auspicious occasions and virtuous action.

Phoenixes can be found on textiles, jars, bowls, plates, paintings and jewelry. A couple of visual markers have been used to set phoenixes apart from other birds, mythical or not. According to the Erya (尔雅), the oldest surviving Chinese encyclopaedic volume, the phoenix has a cock's head, a snake's neck, a swallow's chin, a tortoise's back, and a fish's tail. These attributes tend to be stylised in visual portrayals, with its avian features, such as feathers and talons, emphasised. Within Chinese literary tradition, the phoenix was also said to rest only on branches of the paulownia tree. This meant that in visual depictions, the mythical bird would often be accompanied by lush foliage.

⁵ Panel with Phoenixes and Flowers

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. 14th century

⁶ Robe

Victoria & Albert Museum, c. late 17th century - 18th century

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. 14th century

⁶ Robe

Victoria & Albert Museum, c. late 17th century - 18th century

It was also point of reference for many post-Mongol Persian visual representations of the simurgh. With the Mongol conquest of China and much of Central Asia, well established travel routes between the two regions were reinvigorated, facilitating trade and cross-cultural exchanges. Looking at depictions of the simurgh and the fenghuang, many scholars have noted the clear resemblance between the two.

⁷ Phoenix, Xu Bing

MASS MoCA, 2008 - 2010/2012

MASS MoCA, 2008 - 2010/2012

GARUDA

The garuda is a mythical bird or bird-like creature that can be found within Hindu, Buddhist and Jain traditions. Although these three religions emerged in India, they took root in other places such as Maritime Southeast Asia, Nepal and Tibet. As such the manifestations of symbols such as the garuda are varied across places, and it has been localised to the various cultures within which these religions or philosophies were practiced.

⁸ Finial with Garuda and Naga

Honolulu Museum of Art, c. 12th century

⁹ Tantric Painting of Garuda

Philadelphia Museum of Art, c. 19th century

Honolulu Museum of Art, c. 12th century

⁹ Tantric Painting of Garuda

Philadelphia Museum of Art, c. 19th century

Within Hinduism, the garuda is the mount (vahana) of the god, Vishnu.7 The eagle-like creature is divine, and has been carved into temple gateways and pillars. In The Mahabharata, the garuda emerges as immortal and Vishnu's mount after completing an astonishing quest.

In comparison, garudas within Buddhist tradition are a species of mythical beings. They are often seen in opposition to nagas, which are serpentine mythical beings that feature in The Mahabharata as well. Garudas are seen as having a protective function, and they were charged with the protection of Mount Meru.8

In comparison, garudas within Buddhist tradition are a species of mythical beings. They are often seen in opposition to nagas, which are serpentine mythical beings that feature in The Mahabharata as well. Garudas are seen as having a protective function, and they were charged with the protection of Mount Meru.8

¹⁰ Krishna on Garuda

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. second half of the 9th century

¹¹ Garuda Finial

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. late 12th – early 13th century

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. second half of the 9th century

¹¹ Garuda Finial

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, c. late 12th – early 13th century

Cult images are often made of those who have attained moksha in Jainism. A pair of guardian deities, the yaksha and yakshini, will accompany the figure. Within this tradition, the garuda is the yaksha of the sixteenth Jain Tirthankar Shree Shantinatha.

Depictions of the garuda oscillate between the zoomorphic and the anthropomorphic. Today, the image of the garuda can be found on national emblems of countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia.

Depictions of the garuda oscillate between the zoomorphic and the anthropomorphic. Today, the image of the garuda can be found on national emblems of countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia.

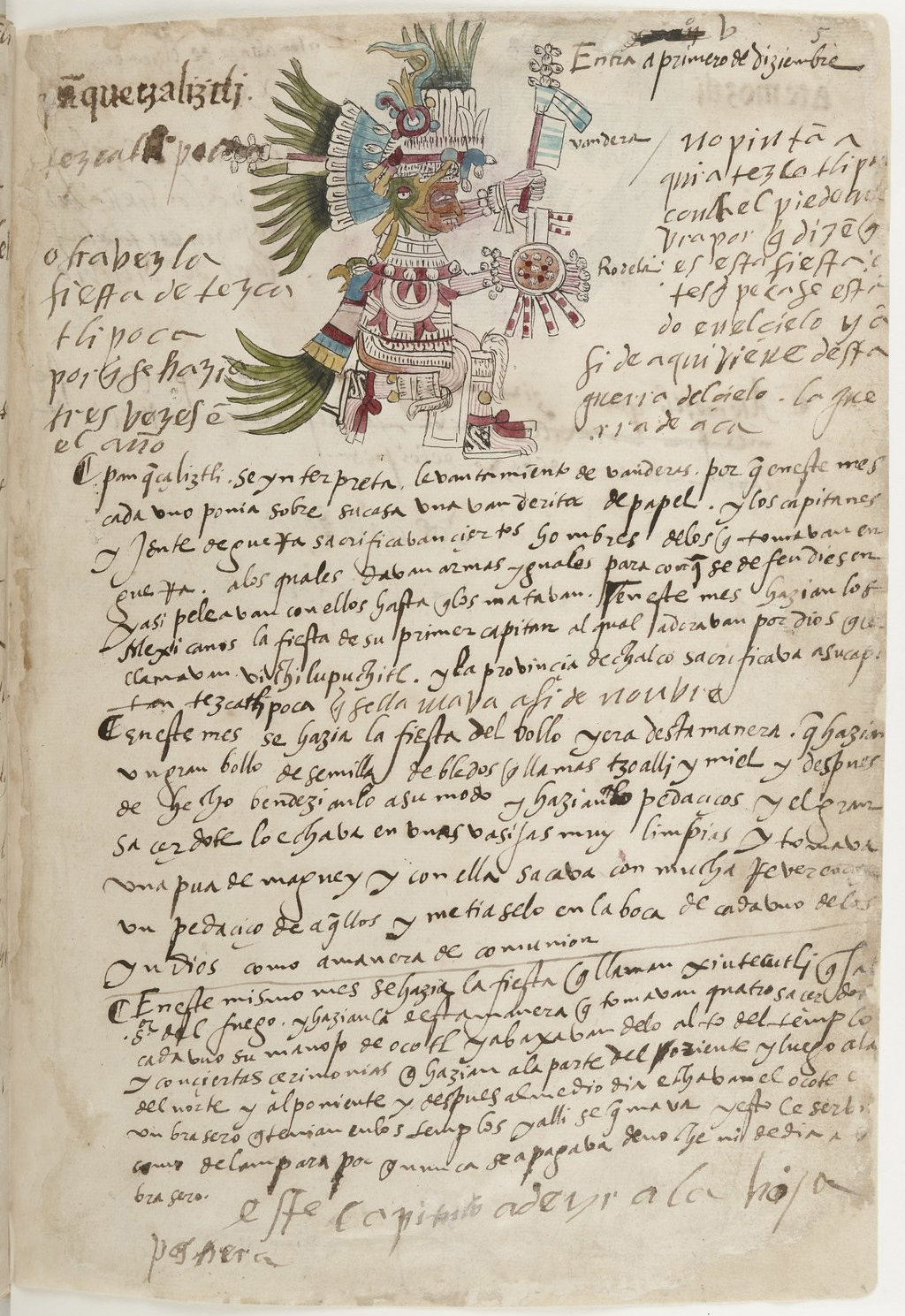

HUĪTZILŌPŌCHTLI

Huītzilōpōchtli (pronounced weetz-ee-loh-posht-lee) is the Aztec deity of war, military conquest, sun, and sacrifice.9 The deity’s name translates into “Southern hummingbird" or “left-handed hummingbird".

There are differing versions of his origin story, but the most well known retellings feature cosmological themes of creation. Huītzilōpōchtli was born to Coatlicue, the goddess of Venus. Huītzilōpōchtli's siblings, Coyolxauhqui and Centzon Huitznahua, were the goddess of the stars and gods of the stars respectively. The story goes that Huītzilōpōchtli's siblings plotted to kill Coatlicue when they discovered that she was with child. As the siblings attempted to decapitate their mother, Huītzilōpōchtli emerged from her womb and dismembered Coyolxauhqui. All of this relates to his standing as one of the most important gods within the Aztec pantheon. A capstone excavated from the site of the Templo Mayor depicts Coyolxauhqui dismembered.

¹² Great Coyolxauhqui Stone

Museo del Templo Mayor, c. 1473

Museo del Templo Mayor, c. 1473

One can often identify Aztec deities in art through observing their dress, facial markings or accessories.10 Huītzilōpōchtli has been portrayed either as a hummingbird or an anthropomorphic figure wearing a hummingbird behind his head, or headgear in the likeness of a hummingbird. As the god of warfare, he is often depicted in full armour and holding a scepter in the shape of a serpent.11 In the centre of Tenochtitlan, a large city in the Mexicas, a large temple was dedicated to both Huītzilōpōchtli and Tlaloc (the Aztec god of rain and fertility). This temple, the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, represented the entirety of Aztec worldview.12

“Together Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli encompass the natural and social universe of the Aztec empire. While Tlaloc was a god of earth and rain, Huitzilopochtli stood for the sun and the sky. Tlaloc marked the time of rains; Huitzilopochtli scorched the earth, with sun and war, in the dry months.”

¹³ Huītzilōpōchtli in Codex Telleriano-Remensis

Bibliothèque nationale de France, c. 16th-century

¹⁴ Huītzilōpōchtli in human form in Codex Telleriano-Remensis

Bibliothèque nationale de France, c. 16th-century

Bibliothèque nationale de France, c. 16th-century

¹⁴ Huītzilōpōchtli in human form in Codex Telleriano-Remensis

Bibliothèque nationale de France, c. 16th-century

Translating oral or textual descriptions into visual formats necessitates processes that are complicated and dynamic. With regions and cultures that were connected by overland and maritime trade routes, it is clear that these interactions allowed for pictorial motifs, religious tradition, and even mythical creatures themselves to be shared, exchanged and referenced. This, coupled with rich local traditions, gave rise to depictions of mythical bird-like beings that were unique yet intertwined.

Stories form the very basis of many cultures. Although we’ve come a long way from gathering around a storyteller, we still are enthralled by modern day tales, both real and imagined. The philosopher David Hume attributed this to causal relations, as we consider ideas of cause and effect. Albeit simplistic in his essentialisation, it is interesting that questions about the existence of universalising myths continued to perplex Enlightenment scholars. Myths have always been a way of explaining and understanding the natural and inhabited world, and because of this, they will always captivate our imagination.

Stories form the very basis of many cultures. Although we’ve come a long way from gathering around a storyteller, we still are enthralled by modern day tales, both real and imagined. The philosopher David Hume attributed this to causal relations, as we consider ideas of cause and effect. Albeit simplistic in his essentialisation, it is interesting that questions about the existence of universalising myths continued to perplex Enlightenment scholars. Myths have always been a way of explaining and understanding the natural and inhabited world, and because of this, they will always captivate our imagination.

FOOTNOTES:

¹ Schmidt, Hanns-Peter. “SIMORḠ." Encyclopaedia Iranica. Accessed 14 January, 2019. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/simorg.

² Reinert, B. “AṬṬĀR, FARĪD-AL-DĪN." Encyclopaedia Iranica. Accessed 16 January, 2019. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/attar-farid-al-din-poet.

³ The David Collection. “Symbolism in Islamic Art." Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/cultural-history-themes/symbolism/art/32b-1987.

⁴ National Palace Museum, Taiwan. “The Dragon and The Phoenix in Chinese Art." Accessed 16 January, 2019. http://www.npm.gov.tw/exhbition/dro0001/english/c1main.htm.

⁵ Carboni, Stefano and Qamar Adamjee. “A New Visual Language Transmitted Across Asia." Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/khan4/hd_khan4.htm.

⁶ Wardwell, Anne E. “Flight of the Phoenix: Crosscurrents in Late Thirteenth- to Fourteenth-Century Silk Patterns and Motifs." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 74, no. 1 (1987): 2-35.

⁷ Dehejia, Vidya. “Recognizing the Gods.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gods/hd_gods.htm.

⁸ O'Brien, Barbara. “Garuda: Divine Bird Creatures of Myth.” Thought Co. Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/garuda-449818.

⁹ Maestri, Nicoletta. “Huitzilopochtli: The Aztec God of the Sun, War, and Sacrifice.” Thought Co. Accessed 14 January, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/huitzilopochtli-aztec-god-of-the-sun-171229.

¹⁰ Guggenheim. “Gods & Rituals.” Accessed 14 January, 2019. https://www.guggenheim.org/arts-curriculum/topic/gods-and-rituals.

¹¹ Boone, Elizabeth H. “Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, no. 2 (1989): 5.

¹² Guggenheim. “Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Axis Mundi of the Universe.” Accessed 15 January, 2019. https://www.guggenheim.org/arts-curriculum/topic/mexico-tenochtitlan.

² Reinert, B. “AṬṬĀR, FARĪD-AL-DĪN." Encyclopaedia Iranica. Accessed 16 January, 2019. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/attar-farid-al-din-poet.

³ The David Collection. “Symbolism in Islamic Art." Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.davidmus.dk/en/collections/islamic/cultural-history-themes/symbolism/art/32b-1987.

⁴ National Palace Museum, Taiwan. “The Dragon and The Phoenix in Chinese Art." Accessed 16 January, 2019. http://www.npm.gov.tw/exhbition/dro0001/english/c1main.htm.

⁵ Carboni, Stefano and Qamar Adamjee. “A New Visual Language Transmitted Across Asia." Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/khan4/hd_khan4.htm.

⁶ Wardwell, Anne E. “Flight of the Phoenix: Crosscurrents in Late Thirteenth- to Fourteenth-Century Silk Patterns and Motifs." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 74, no. 1 (1987): 2-35.

⁷ Dehejia, Vidya. “Recognizing the Gods.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gods/hd_gods.htm.

⁸ O'Brien, Barbara. “Garuda: Divine Bird Creatures of Myth.” Thought Co. Accessed 16 January, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/garuda-449818.

⁹ Maestri, Nicoletta. “Huitzilopochtli: The Aztec God of the Sun, War, and Sacrifice.” Thought Co. Accessed 14 January, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/huitzilopochtli-aztec-god-of-the-sun-171229.

¹⁰ Guggenheim. “Gods & Rituals.” Accessed 14 January, 2019. https://www.guggenheim.org/arts-curriculum/topic/gods-and-rituals.

¹¹ Boone, Elizabeth H. “Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, no. 2 (1989): 5.

¹² Guggenheim. “Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Axis Mundi of the Universe.” Accessed 15 January, 2019. https://www.guggenheim.org/arts-curriculum/topic/mexico-tenochtitlan.

FURTHER READING:

¹ Whilst preparing for this post, we came across a blog that discusses the influence of birds on culture. It goes into further detail as to just how strong and established the connection between human society, human imagination and avian critters is.