Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Technological Materiality

Issue: On Technological Materiality

Fyerool Darma is an artist based in Singapore. He draws on an extensive visual vocabulary from popular culture, archival material, literary references, the Internet and the artist’s lived experiences. Engaging actively with object and material experimentations, his installations often incorporate elements of imaging, sculpture and digital or time based media.

Filed under: graphic design, installations, internet art, sound, technology, textiles, text

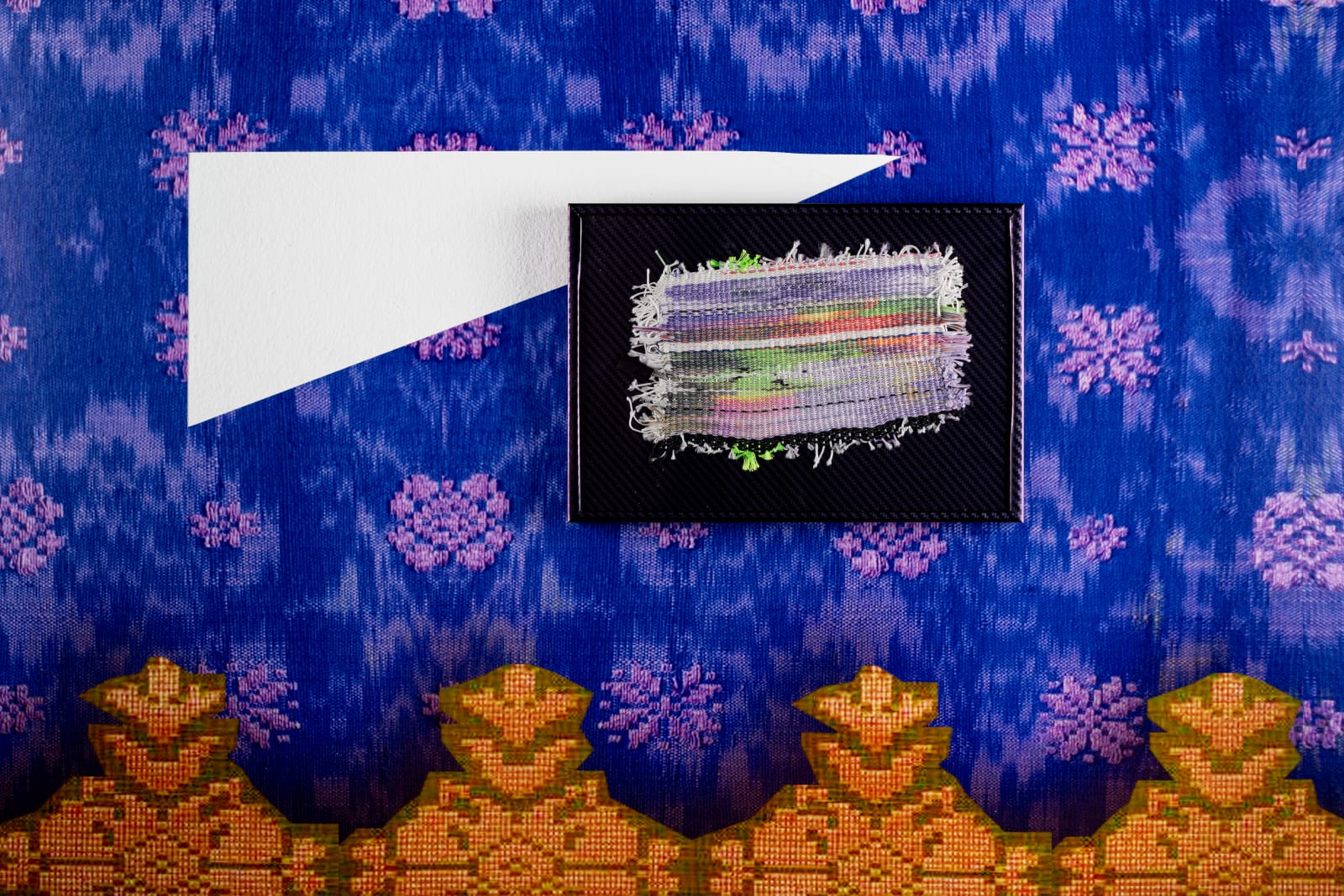

¹ Screenshot from Gertie the Dinosaur, directed by Winsor McCay

1914 [Accessed through Open Culture, https://youtu.be/32pzHWUTcPc, 1 December 2022, 3:17 PM]

² Screenshot from Upin & Ipin — Dino Land Adventures (Season 11)

2017[Screen captured in 2022 by Wardah Mohamad]

Let’s start with the selection that you picked out for this conversation. Two of the images strike me immediately: screenshots from Gertie the Dinosaur and Upin & Ipin — Dino Land Adventures. The former is from the earliest animated film to feature a dinosaur, and latter is an episode from Malaysian CGI animated series where the characters go on a journey through prehistoric times. Why did you choose these animations, and how do you see them in relation to each other?

These entry points were prompts to think about concepts of time and life, the fantasy of dinosaurs, and the distances we have crossed as a civilisation. When one thinks about dinosaurs from a human perspective, there is an element of fantasy. Of course they existed, but I question the imagination around what contributed to their extinction, and what we have mined from the stories of dinosaurs. Beyond that, I also have a fascination about how there's a constant search or desire to watch the other, which in this respect, is the non-human, the dinosaur. Gertie the Dinosaur, was one of the earliest animated films. The dinosaur is especially positioned in between extremes where it’s either adorable, or it’s very violent. A more contemporary example of this would be Jurassic Park. I always question, who's the one reading or watching it?

For Upin and Ipin, the time period and context is quite interesting. Of course, it's not the earliest example of animation within Southeast Asia, nor the earliest animation that deals with ideas of dinosaurs and their histories. But what I picked up was the storyline — of going into a certain time, the idea of return and the loop. When the characters go back in time, they are in a loop. However, they also exit that loop after a certain period. These two metaphors of the dinosaurs are, for me, timestamps. They represent the concepts I invested time towards exploring, which resulted in the material obsessions and fascinations I had. I also like to think of them more metaphorically as another language device. Additionally, the simulation of the dinosaur as a beast and monster is a recurring theme in displays. Lastly the idea of the Jurassic period, as the period from which fossil fuels came from, is also one that is interesting to reference. These are the kind of questions I was trying to point out.

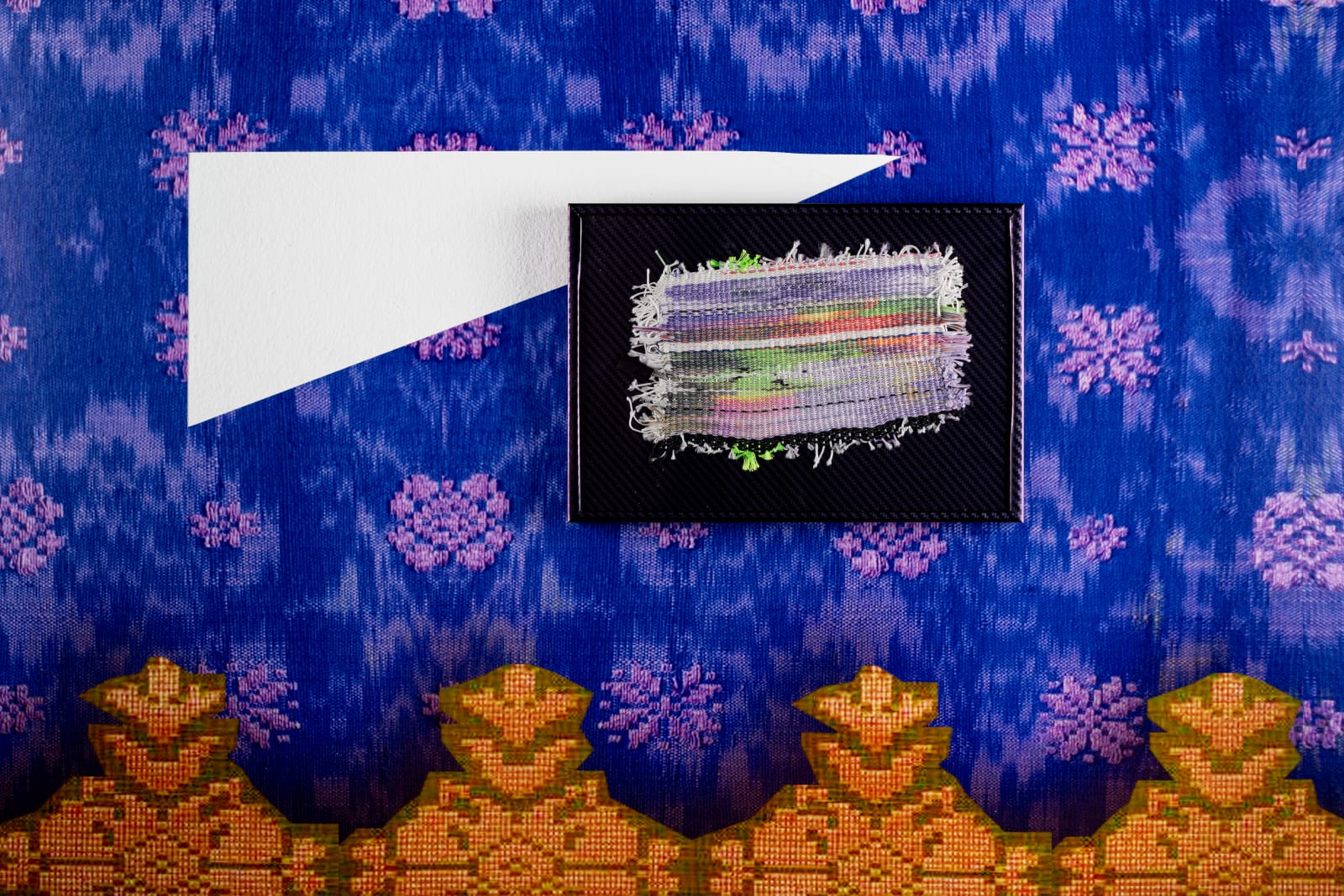

³

Screenshot 14-12-2021 at 09.09 AM (2021),

Fyerool Darma

2021, Installation view at Yeo Workshop

⁴ Screenshot 02-12-2021 at 01.01 AM, Fyerool Darma,

2021, Installation view at Yeo Workshop.

2021, Installation view at Yeo Workshop

⁴ Screenshot 02-12-2021 at 01.01 AM, Fyerool Darma,

2021, Installation view at Yeo Workshop.

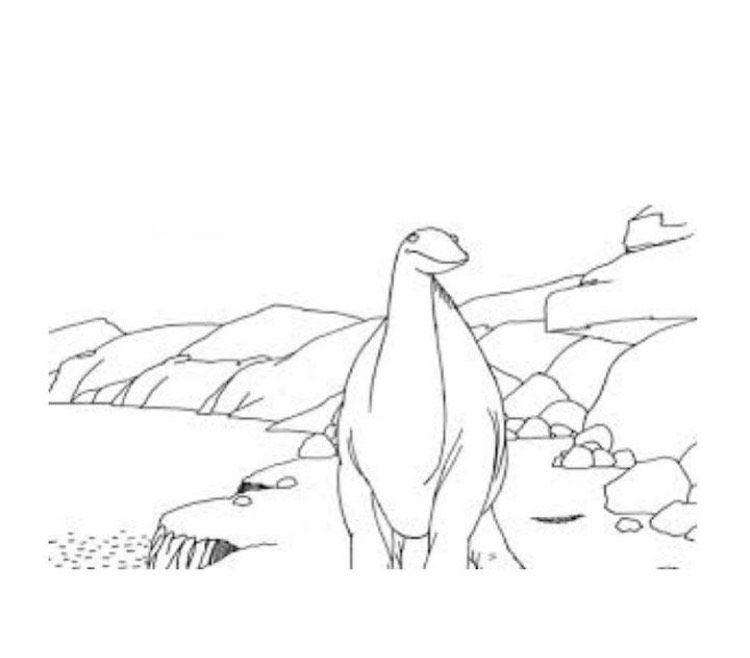

The main place I've seen dinosaurs feature in your work is in your previous exhibition at Yeo Workshop, l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$, where you included a dinosaur colouring sheet on the back of the exhibition handout. Can you tell me about the colouring sheet and what animated dinosaurs have brought to your work?

It grew from an intention to just play. The exhibition l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$ was an exercise or several exercises from conversations, sharing, and playing with curator Dr. Karin Oen. We didn't exchange readings but we shared gems in the forms of sounds and music, through which we tried to find a vibe we could play around with. That was when I was much more aware of the changes in my understanding of certain visual metaphors. For instance, I think of dinosaurs as patterns with several codified meanings. I think everybody has their own ideas of what the word “Jurassic” or “prehistoric” means, much like how some outside Southeast Asia have preconceived ideas of the Southeast Asia landscape. It's almost revealed as another prehistoric layer. From that perspective, are we then the dinosaurs, and how do we move out of that misconception?

The inclusion of dinosaurs also came from a pure moment of wanting people to see something that’s not in colour and prompt an urge to draw on it. But I think everybody just loves dinosaurs. We tested it out on audiences as an invitation for them to grab and use it as material of their own. This was also soon after the pandemic lockdown measures were eased, and there were many sensitivities around interactive works. It felt like the lockdown created a stop or a pause, but also a phobia around the things that we touch. This was a way for us to respond to the landscape of that period.

⁵

Exhibition handout, Fyerool Darma: l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$, 15 January – 27 February 2022, Yeo Workshop, Singapore

Credit: Colouring sheet design by studio cinoti

Credit: Colouring sheet design by studio cinoti

⁶ Photo of pattern made with Plus Plus toy as assembled with Dahlia in 2022

Credit: Fyerool Darma

On the topic of play and use of patterns, another image that you selected for this conversation was a photograph of this colourful interlocking pattern made with Plus Plus, a plastic toy, that was assembled with Dahlia, your daughter. You’ve spoken a bit about playing, how would you describe the place of play in your practice?

It's a constant. For me, play doesn't have to be an action. It can just be a thought, because that's where certain actions get exercised in your mind. But in terms of its physical materiality, I constantly play and test if, for example, material A and material Z can be mixed together. It’s through these strategies and methodologies that you understand if certain things vibe together or not. It's almost like music, where certain notes can never fall into one song together. But once you find the right theme, then you can play that rhythm.

I use that philosophy in my own building of knowledge as well. There are moments where I read a lot, but I will also dissect every single thing and start playing with theories, writers and so on. One example of this would be me pulling them back to non-serious subjects, and that’s where the prompts of Upin and Ipin and Gertie the Dinosaur come into play. There’s a constant conversation of how to relate it back to other individuals. It's a constant mode of communicating or creating metaphors.

For me, play doesn't have to be an action. It can just be a thought, because that's where certain actions get exercised in your mind.

It's interesting that you use the word metaphor. For me, I see that as making connections between two things that don't seem to be connected, and you're bringing them into conversation.

What's interesting about the metaphorical is that it doesn't need to have a meaning or reason. It's also a codified language. For example, I don't even understand certain metaphors, as writers have their own embedded codes, and it's the beauty of language. Metaphors also never exist within a binary, and they can have multiple meanings. It’s something that I find interesting, especially when I start playing with or re-mixing different materials with different scopes.

Another way we’ve talked about your work in the past is the notion of remixing or foraging of different sources. Your practice draws on the diverse, dense and shifting hypervisual stream of information in digital communication, but also from historical archives and research materials. These references often transcend history and geography and are brought in conversation with each other. Could you share how you make decisions about bringing materials together, and what you choose to include or exclude? Or is a lot of it quite intuitive?

Well that’s the thing, intuition really guides my entire practice. But at the same time, intuition also creates the glitch, which I'm always looking for. I only realised it three years ago — I think the constant search and question I have is: What is the relevance of these materials that I use with the time that we're experiencing? Do they have their space and do they have an economic or cultural value? But at the same time, what's interesting about the things I employ in my exercises is that what guides them first is always the vibe and how much I feel for them. Sometimes I feel it's ancestral intelligence that speaks, and their voices guide it.

I tried to distil and work purely with materials quite recently. One of the most recent examples is the Screenshot series. It started off as a fascination with carbon fibre vinyl and understanding the components that make up this amazing material. Carbon fibre is very light, almost weightless, but with incredible strength. Engineers wanted to use carbon fibre to make vessels that can bring individuals to outer space. Carbon fibre was also first used in some of the first light bulb displays of the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. The Exposition also had its complexities — there were human zoos. So this idea of lighting and display raises questions of what's being displayed, who gets to display, and who gets funding for it. These get woven into the material. I like that it adds a different layer to how we view or understand exhibitions. It's these kinds of narratives that I'm constantly interweaving within my work, not just as a way to talk about the history, but to amplify the question of how much have we moved beyond the parameters of history. Who are we speaking to, and what are the pursuits we are working towards?

⁷ Screenshot 22-11-2022 at 22:22 AM (siu dai UHD) featuring Lé Luhur and LKS, Fyerool Darma

2022

2022

⁸ Screenshot of 'Carbon fibres reinforcing a stable matrix of epoxy' from DragonPlate

For this conversation, you also selected a screenshot of ‘Carbon fibres reinforcing a stable matrix of epoxy’ from DragonPlate, a carbon-fibre composite supplier. For me, the cross-section of the industrial material simultaneously evokes digital flatness and fossilised stone. Why are you drawn to this image, and do you see these tensions inherent in other materials?

DragonPlate produces materials for construction. They get their carbon fibre from China and tweak them to their requirements. In this image, the carbon fibre is used as a reinforcing tool for building and construction work. What’s interesting is that it’s made with a twill weave, where multiple strands and components are translated into one object.

This is something I was trying to outline in my work as well — all these materials come from different parts of the world, and they get translated into a new material. It also goes back to the idea of weaving, which I've had a fascination with. The reason why carbon fibres are so strong is because of the interlocking weave. Weaving is an ancient knowledge, and it's something that is constantly employed within the industrial economy. Carbon fibre is used in shoes, bridges, buildings, bicycle frames and even sunglasses or spectacles. It's quite strange to think that such an easy method basically converts textile techniques into a hardened material. Weaving itself is also a humanist approach to making. We are constantly interweaving narratives, all the time. That influences my approach in art making, and in some ways is a metaphor for how to experience the world.

In my artworks, I haven't reached the point where I can actually use carbon fibres for my frames — we're still developing the R&D side. But we use vinyl to cover aluminium alloy frames. Aluminium alloy is also an interesting material, it’s mostly used in space shuttles and rockets because of its lightweightedness and similarity to the properties of carbon fibres. For the series Screenshots, we used frames covered with vinyl to give the illusion of carbon fibre, and at the same time it acts as an added skin. Because when you protect something, you are also hiding it away from view — there's always an obfuscation that I’m playing with.

On that note of skins, textures, and patterns that mimic materials, you also manipulate the physical and the digital in many of your works. For example, in l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$, your woven pieces were re-weavings of printed images on polyester threads, which were presented alongside digital reproductions of songket textiles or other traditional weaves. What is your approach to craft and creation, and how do you think about this tension between the physical and digital?

It was the result of several accidents and jumps, but what guided it was thinking about how I could weave the narratives together. I was thinking about the idea of translations — translating images onto surfaces and interfaces — and how we could capture moving images that we constantly consume everyday. Textiles, to me, are a type of interface, as well as a protective skin. I was also thinking about painting: questioning what a painting is, in today’s context, and the moment that paintings became mobile. Today, paintings and artworks are expected to be mobile to travel to art fairs and shows, but in earlier days, textiles were actually the cultural materials that were mobile. When interweaving all these ideas together, the transmission of the image just became natural. It came from a child-like fascination to experiment with weaving.

Gradually I realised that through weaving, I was not obfuscating the image. Instead, I was failing to completely capture it. In that sense, I was actually making a painting, but instead of using the brushes or paint, I was going thread by thread with printed images. That's why I think of them more as imaging, rather than collage or assemblage. It was also interesting to consider it as another exercise in creating distance from the work. I asked myself, how can I translate that where the hand is not seen? It's an aspiration to reach that almost perfect moment — that's why weaving is a nice exercise, because it allows for the precision to be filled.

Textiles, to me, are a type of interface, as well as a protective skin.

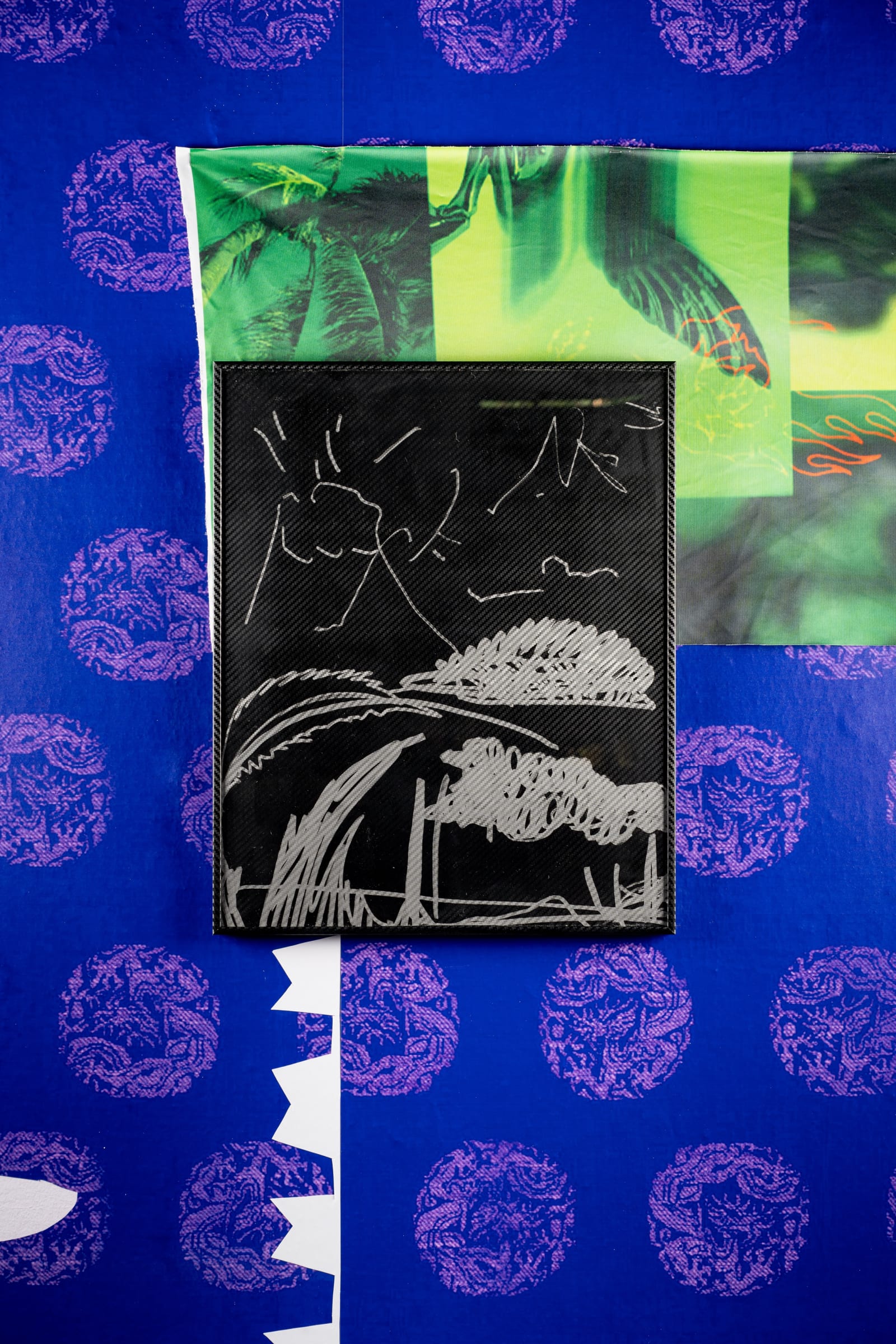

⁹

Fyerool Darma: l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$

2022, Installation view at Yeo Workshop

2022, Installation view at Yeo Workshop

The vinyl and images of textiles were presented as multi-layered installations which inhabit both three- and two-dimensional space. How has the physicality of a space you work in and the exhibitionary format affected your working processes?

I think there were several elements that really affected how the installation looked. We weren't thinking of designing, but rather how we could make a painting from non-painterly material. When we first installed it at Yeo Workshop, the vinyl was all pasted beautifully, and I moved around the space and did my dance — cutting forms and images from my memory bank in a decisive moment by hand. It reminded me of Lucio Fontana’s slashed works. That moment became so ridiculous, it pushed paintings into a different spectrum. I was thinking about how I could push the material of vinyl, because it’s used everywhere, in advertising, design, and art. The vinyl itself becomes the skin to these cosmetic surfaces and it changes the effect and scale of one's experience. The space and the walls become the canvas, the vinyl is the gesso, but after cutting up and rearranging, that’s when the painting takes form.

The collaborators I brought in also affected the works. When shown in Singapore, we had the liberty of time, so they assisted in drawing out or carving forms based on a word or sound trigger. But when the work was shown in London and Korea, unfortunately we didn't have enough hands to assist with the cutting. With the new series, Screenshot, I work with a set of collaborators who come into the studio. We first settle on a vibe or sound that will loop for four to eight hours. It reminded me of when I was employed as a worker in a production-line-like environment, punching in keys on a computer. I used that as a template in a space for art production to play with areas of experience I could affect.

I asked my collaborators to slice the vinyl and paste them in a manner that would create an irregular pattern. In fact, it’s hard for many to reach an irregular pattern —they tend to follow the pattern down to the inch. So we switch up the beat, and that’s where an irregular pattern can come into effect, and new patterns emerge. Screenshot is actually an exercise in finding irregular patterns and modes. Now we’re also figuring out how this exercise may be freed from a particular size or format, so the irregularities can go beyond the restriction of the frame.

¹⁰ Gong 3000, Jonathan Kusuma

2021

2021

It's interesting how, even if you aspire for irregularity, randomness, or glitch, there are some parameters within which they take place. This seems like a good time to talk about Gong 3000 by Jonathan Kusuma, which you also picked out for this conversation. It’s a hypnotic techno track built around the massive sound of a synthetic gong, with gamelan sounds woven in at the end. What was your response to this piece, and how do you see that response reflected in the works you’ve made?

I've always been a big listener of Jonathan Kusuma’s works because I learnt a lot about rhythm in between gestures. Gong 3000 really reminded me of Jose Maceda’s ideas around drone and melody, as well as the ethnomusicology of Southeast Asia. These discordances are different kinds of gestures and approaches, but also act as a bridge between the melody and rhythmic patterns. It's almost like creating the water breaker where the waves can be redirected back. But it's not a stop, and it's not a pause even. It’s a way to play with time in the composition of sound and music.

In Gong 3000’s introduction, a context isn’t given, but as you go along, this context is suggested closer to the end. At the same time, the sound could be a sample of anything, but it's what you project onto it that prescribes its meaning. I also use Kusuma’s sound work as an example because it's so light despite its content — the kind of places he gained experiences from are reflected in his sounds. The work itself is also a nice suggestion to think about the gong’s place within the technosphere. The sound of the gong is created by two materials that are knocked together, but it results in an aura that really hits an internal space. Gong 3000 made me rethink what could be music.

You also regularly collaborate with berukera to produce music which similarly draws on a polyphony of sources and references, in a literal re-mixing of contexts. Tell us about how music plays into your practice.

I regularly employ berukera as another collaborator, and it was through working with them that I understood this idea of pattern, patterning and re-patterning, and how I can think beyond the visual. Our collaboration started during prep-room: After Ballads at NUS Museum, but it became more serious when I was in residence at NTU CCA Singapore. We started off playing with remixes and thinking about how we could sample from an existing space. One often thinks about sound as contextual, but I started to find that position quite restrictive. At this present moment, one of the most exciting exercises that we're doing is to convert patterns that exist from textiles into sound. These are exercises in maximalism and thinking about how different elements could be heard as one singular harmony or discordance.

We also employ several “artificial singers” by using text-to-speech generators to read out poems and play with the keys and rhythms that it reads. For example, we use a lot of auto-tune. In auto-tune, one key is mismatched, which produces the ‘off-tune-ness’ that you hear. At the same time, it makes the voice sound more real.

One often thinks about sound as contextual, but I started to find that position quite restrictive.

¹¹

Poietics of Pantun/Pantoum (featuring b*ntangLV786, berukera, jaleejalee, Lee Khee San, ToNewEntities, @sgmuseummemes and moyangz from NUS Museum’s South and Southeast Asia Collections and Autaspace), Fyerool Darma

2022, Installation view at National Gallery Singapore

2022, Installation view at National Gallery Singapore

The conversions from text-to-speech reminds me of the close historical relationship poetry has to music and verbal readings of text. Another recurring interest in your practice is text and language — from lyrical pantuns and rhyming quatrains to hip-hop verses and soulful ballads. Your recent project, Poietics of Pantun/Pantoum/Matuntun/tuntun ..., delves into this. Tell us more about your process making this work.

The work Poietics of Pantun/Pantoum/Matuntun/tuntun ... was really an exercise in understanding how one writes about or captures their surroundings. We either describe it in words or draw it, and it moves between the two. Within the spaces and landscapes of our hyperreal present, they merge. The idea that texts are images, or that images are texts, takes form in this instance, to the point where images become flattened or stand in for words. That's where memes emerge.

This work was initially titled The Pantoum: Overwrite A Famous Pantun, and it was produced for a digital platform. The work historicised or rewrote the history of pantun as a subversive attempt to obfuscate the real, transforming it into a mode that becomes almost inauthentic. The work also prompted me to ask how we could move beyond the parameters of language itself. Do we now tell the story, or do we still hide the story from those spaces?

I like that it doesn’t say that much, it just creates a possibility for pantun mistranslations, and a space where cultural ownership can be explored. There's a question about who gets to own certain parts of that culture, and it goes back to the idea of remixing. Remixing is actually a natural process, and that’s where you see the growth of a certain culture. It also allows us to rethink these global modes of expression. Words are mobile and transmitted easily. They do not require a physical vessel to move from one place to another. In the most updated version of our world, the internet is a space for the sharing and distribution of images. Similarly within several genres of pantuns, there’s no authorship. That's where remixes happen naturally. It gets sampled verbally again and again. Poietics of Pantun/Pantoum/Matuntun/tuntun ... was initially distributed through WhatsApp, along with a pseudo-advertisement. I was playing with the idea of that in-between — between what is real and what is not — and it was an exercise in trying to locate that hyperreal moment in our contemporaneous present.

Words are mobile and transmitted easily. They do not require a physical vessel to move from one place to another. In the most updated version of our world, the internet is a space for the sharing and distribution of images.

¹² Photo of a customised Personal Mobility Device captured in NorthPoint City, Yishun, 2022

Credit: Fyerool Darma

There’s one more photo you picked out of a customised Personal Mobility Device (PMD) outfitted fully with sunshades, the device almost like an extension of the body to be worn. Tell us more about this image and why it fascinates you.

That was an image I took. I think this is an exercise that everyone does, wandering around and taking photos of what they like. I use photography as another way to sketch ideas. It's almost like a timestamp.

I’ve always been fascinated by how individuals customise and personalise things, and as an observer, it teaches me a lot about what art is or should be. The PMD is an interesting object, because it provides protection whilst expediting the everyday. It’s this idea of speed where, especially in the context of Singapore, we constantly desire everything to be expedited.

For me, the PMD is actually an extension of the body. It's almost like the body becomes dependent on it, and in a world where expediting is the norm and that acceleration becomes the language or philosophy, is there anything left to be expedited? The PMD becomes a good metaphor for that — being reliant on a machine to bring us from point A to point B. I was inspired to create and design my own PMD. We haven't materialised it yet, but I’ve been thinking of the projects we can put it in. I like to allow ideas to simmer and wait for the right time to make the entire thing from scratch.

In relation to this, I was curious about your recent works around the Maphilindo Confederation. You reference the notion of ‘Kitsch-men’ in relation to Southeast Asian visual vernacular and political alliances. I’m curious about your interrogations on the question of Southeast Asian regionalism, its political complexities, and how it sits alongside, perhaps, the older shared history of the Malay Archipelago. How do you see these regional histories and the gaps that lie between them?

This series of works extend the idea of archipelagic thinking and terrain-forming narratives. It went through several readings. Firstly, it was initiated in 2020, for the exhibition, In Our Best Interests: Afro-Southeast Asia Solidarities during a Cold War at NTU ADM Gallery. We were looking at affinities that disperse but also contain these conversations. For me, it's always been a fascination to find these kinds of thought from a direct vicinity, and how it relates back to the larger archipelago and terrains beyond. In relation to the Kitsch-men, I tend to create certain avenues to confuse the viewer as a way to obfuscate and protect a certain narrative identity. In the translation of Kitsch-men, I thought about how the Kitsch-men is not a real person, but just a persona. The suit becomes a skin that protects and is comfortable at the same time.

When the work was presented at ART SG in 2023, it took a different tone. It was almost compressed to the point of flatness because it was contained within a vitrine. The question of what is on display is still left open, because we are still negotiating who that Southeast Asia person is. In certain Western spaces, they assume that a Southeast Asian person is someone who is authentic and grounded in their tradition and roots. You can be grounded in your roots, your narrative and your histories, but still go beyond that, whilst not wearing that garment. For me, it was a work that questioned the positionalities and the disaffinities of what contributes to Southeast Asia as a regional identity. However, it’s not aspiring towards unified regionalism. It questions where Southeast Asia is in the space of many differences and discordances, and how would all of them sit together. It’s an open question.

¹³ KITSCHMENSCH WITH MANY FAILED FLAGS OF 1963 MAPHILINDO CONFEDERATION (REWORKED),

Fyerool Darma

2021- 2023

Credit: Jaya Khidir

¹⁴ KITSCHMENSCH WITH MANY FAILED FLAGS OF 1963 MAPHILINDO CONFEDERATION (REWORKED), Fyerool Darma

2021- 2023

2021- 2023

Credit: Jaya Khidir

¹⁴ KITSCHMENSCH WITH MANY FAILED FLAGS OF 1963 MAPHILINDO CONFEDERATION (REWORKED), Fyerool Darma

2021- 2023

What is the role of fact and fiction, and the slippage between them, in your work?

The slippage between fact and fiction drives how I create works from various sources. Going back to the idea of remixing, once a material is sampled, the sample is sampled again. Yes, you are giving credit where credit is due, but at the same time, you're bringing it into a new space. That journey is what interests me. It's not about going back to that sample, but exploring how much more I am able to push that sample beyond the parameters of its framing.

The slippage between fact and fiction drives how I create works from various sources. Going back to the idea of remixing, once a material is sampled, the sample is sampled again. Yes, you are giving credit where credit is due, but at the same time, you're bringing it into a new space. That journey is what interests me. It's not about going back to that sample, but exploring how much more I am able to push that sample beyond the parameters of its framing.

Going back to the idea of remixing, once a material is sampled, the sample is sampled again.

In your work, you often actively credit the variety of collaborators, contributions, and sources. How do you approach this practice of crediting collaborations, in sampling and remixing in the context of the show, but also acknowledging their origins?

In academic spaces, there’s an etiquette of having a bibliography and references. For me it's similar to giving respect where it is due, and comes from a need to remember these individuals. When one thinks about the production of work, they always assume that there's just one person that produces it and therefore deserves all the credit. That may be true in some instances. But I'm interested to use that space of making to host other ideas or individuals whose practices I vibe with. It’s also about using that space to start other possible collaborations.

This practice started from my time working on prep-room at NUS Museum. I had a conversation with curators Siddhartha Perez and Ahmad Mashadi, and they shared with me the importance of giving credit. Most of the exercises which artists do now have already been done before. It’s another way to honour the past, without trapping them in the time they were in. It's like bringing them out of their cage and taking a walk with them — not on a leash, just walking with them. That’s why, especially for Screenshot, the credits are also necessary to inform future readers that we are not just thinking about one single material and dissecting it into its parts and elements. It highlights a larger pursuit towards thinking about the world as a constant collision of different materials and atoms. For me, the captions and the titles are some ways I reflect this.

In academic spaces, there’s an etiquette of having a bibliography and references. For me it's similar to giving respect where it is due, and comes from a need to remember these individuals. When one thinks about the production of work, they always assume that there's just one person that produces it and therefore deserves all the credit. That may be true in some instances. But I'm interested to use that space of making to host other ideas or individuals whose practices I vibe with. It’s also about using that space to start other possible collaborations.

This practice started from my time working on prep-room at NUS Museum. I had a conversation with curators Siddhartha Perez and Ahmad Mashadi, and they shared with me the importance of giving credit. Most of the exercises which artists do now have already been done before. It’s another way to honour the past, without trapping them in the time they were in. It's like bringing them out of their cage and taking a walk with them — not on a leash, just walking with them. That’s why, especially for Screenshot, the credits are also necessary to inform future readers that we are not just thinking about one single material and dissecting it into its parts and elements. It highlights a larger pursuit towards thinking about the world as a constant collision of different materials and atoms. For me, the captions and the titles are some ways I reflect this.

¹⁵ SCREENSHOT 01-01-2022 AT 03.03AM, Fyerool Darma

2022, Installation view at Yeo Workshop

2022, Installation view at Yeo Workshop