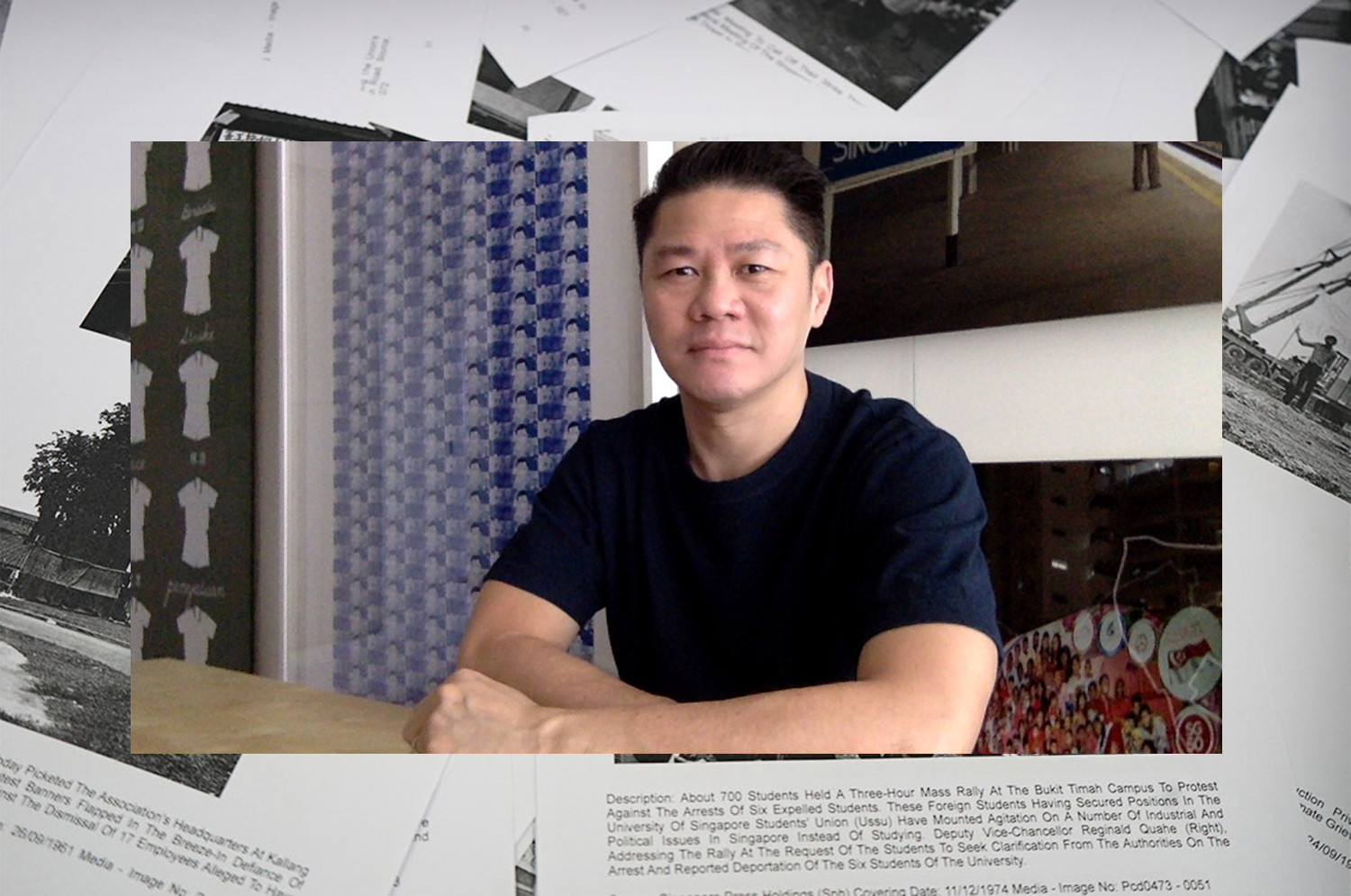

Green Zeng is a filmmaker and artist from Singapore. His art practice explores issues of historiography and identity, and examines how history is scripted, perceived and disseminated.

In 2015, his debut feature film, The Return, made its international premiere in competition at the 30th Venice International Film Critics’ Week. Zeng has also directed short films such as Blackboard Whiteshoes, which was selected for the Cannes Film Festival in 2006, and Passenger, which in the same year was awarded the Encouragement Prize at the Akira Kurosawa Memorial Short Film Competition in Tokyo. As a practicing artist, Zeng has exhibited widely in Singapore and abroad. In 2012, he was a Finalist for the Sovereign Asian Art Prize in Hong Kong. In 2014, he was nominated for the Asia Pacific Breweries Signature Art Prize. He won the Bronze Award in the 26th UOB Painting of the Year (Established Artist Category) in 2018. His most recent solo exhibition Returning, Revisiting & Reconstructing was held at Foundation Cinema Oasis in Bangkok, Thailand in 2019. He is currently an artist in resident at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA) Singapore Residencies Programme in 2020.

Known for his sustained interest in the archive, Green Zeng’s practice interrogates simplistic historical narratives and how we hold these narratives in our minds. Our conversation with the artist stretches across his selection of texts and artworks — with titles such as Judith Butler’s Notes Toward A Performative Theory Of Assembly and Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression sitting comfortably alongside artworks such as Lola Arias’ Veterans and Koki Tanaka’s Activity 5 / Provisional Studies: Workshop #1 “1946–52 Occupation Era, and 1970 Between Man and Matter”. Within Green’s practice, time is stretched out as a continuum. In gathering past and present, Green discusses how his projects propose thoughtful strategies for moving forward.

In 2015, his debut feature film, The Return, made its international premiere in competition at the 30th Venice International Film Critics’ Week. Zeng has also directed short films such as Blackboard Whiteshoes, which was selected for the Cannes Film Festival in 2006, and Passenger, which in the same year was awarded the Encouragement Prize at the Akira Kurosawa Memorial Short Film Competition in Tokyo. As a practicing artist, Zeng has exhibited widely in Singapore and abroad. In 2012, he was a Finalist for the Sovereign Asian Art Prize in Hong Kong. In 2014, he was nominated for the Asia Pacific Breweries Signature Art Prize. He won the Bronze Award in the 26th UOB Painting of the Year (Established Artist Category) in 2018. His most recent solo exhibition Returning, Revisiting & Reconstructing was held at Foundation Cinema Oasis in Bangkok, Thailand in 2019. He is currently an artist in resident at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA) Singapore Residencies Programme in 2020.

Known for his sustained interest in the archive, Green Zeng’s practice interrogates simplistic historical narratives and how we hold these narratives in our minds. Our conversation with the artist stretches across his selection of texts and artworks — with titles such as Judith Butler’s Notes Toward A Performative Theory Of Assembly and Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression sitting comfortably alongside artworks such as Lola Arias’ Veterans and Koki Tanaka’s Activity 5 / Provisional Studies: Workshop #1 “1946–52 Occupation Era, and 1970 Between Man and Matter”. Within Green’s practice, time is stretched out as a continuum. In gathering past and present, Green discusses how his projects propose thoughtful strategies for moving forward.

Tell us about your selection of texts and artworks, particularly with regard to how you put them together. When you say that this selection is relevant to some of your recent artworks, are these works that have served as reference points for your own art works or works that you later encountered and found had resonances with what you were exploring?

When picking out artworks and books for our conversation, I based my selection around things that I've been looking at whilst working on recent projects such as the Television Confession series and the Public Assembly series. I collect information and images from archives and libraries, and both of these projects were sparked off by those gathered materials.In looking for a way to interpret these materials, to discuss them, and to share the information I had, I started looking out for writers and — albeit less often — artists who work with similar interests. These works have served as a source of inspiration and a reference point for me.

¹ Fearless Speech, Michel Foucault

2001

Out of the various texts you picked out, which include titles by Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler, you also included two titles by Michel Foucault in the mix. As a prolific philosopher and thinker, Foucault was known for his work on power, technology and the apparatuses of the state. Why has Foucault’s thinking persisted and emerged within how you make and think about art, and is there a particular idea of his that you find yourself coming back to?

Throughout the course of my artistic practice, I’ve encountered and kept coming back to the works of writers such as Louis Althusser, Judith Butler and Jacques Derrida. Yet with recent projects, I’ve found myself resonating a lot with Foucault’s works. In particular, I’m drawn to his later writings.

I was captivated by Foucault’s writings on concepts such as fiction, truth, power and resistance. I was fascinated by his perspective of truth as something that is produced or constructed. To him, truth is sustained by power relations, and power produces truth. Yet, truth can also be used to modify power relations. I was also fascinated by his assertion that fictions are experiments in truth. Although Foucault thought of fiction and truth as being similar in that they were both produced and constructed, he viewed fiction as having an edge over truth — because fiction allows one to imagine an alternative interpretation of the present.

These are some of the things that I’ve had at the back of my mind whilst working on recent projects. Reading these texts is one thing, but I’m not sure if these writings have actually surfaced within my work.

² The Politics of Truth, Michel Foucault

2007

You mentioned Foucault’s idea regarding fiction as an experiment in truth, and in many ways, what we consider as fiction might actually lie incredibly close to our lived reality. In working with materials the way that you do, do you think of this process as being one that leans towards the formation of fictional narratives or non-fictional rearrangements of situations, ideas and histories — not that it has to be seen in terms of a binary either.

In Foucault’s work, he speaks of how fiction enables us to imagine and come up with alternative interpretations of the present moment. That idea is the gist of what I’m doing now.

There’s a certain fidelity when it comes to the present, yet there is also this sense of openness and possibility. There is never and should never be a concrete resolution or a sense of finality. Unlike what some might think, my work isn’t really concerned with concepts such as nostalgia. I’m interested in opening up possibilities, and encouraging audiences to relook or reconsider some of the things we already have access to.

I’m interested in opening up possibilities, and encouraging audiences to relook or reconsider some of the things we already have access to.

³ Students’ Confession (Television Confession), Green Zeng

2018, Video Still

⁴ Students’ Confession (Television Confession), Green Zeng

2018, Video Still

2018, Video Still

⁴ Students’ Confession (Television Confession), Green Zeng

2018, Video Still

The archive is an endlessly productive site for artistic imagination and historical storytelling, and because of this, it has captured the attention of many artists. Personally, what comes to mind when you think of the archive? Tell us about how this influences your methodology and how you approach the archive and its materials.

Archiving is a subtle form of gatekeeping. Archives make decisions as to what to include or exclude in their collections. As such, they are unable to give us a complete picture or an entire overview of history. Perhaps we should stop thinking of the archive as a place where we can search for facts and truths. Instead, the archive is a place where we can come to our own interpretations of the truth.

Within the tradition of perspectivism, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche would argue that there are no facts, only interpretations. That’s another thought I’ve been keeping at the back of my mind as well.

⁵ Foreign Office, Bouchra Khalili 2015, Installation View at Palais de Tokyo

In particular, let’s spend some time looking at some of the art works you’ve picked out — Bouchra Khalili’s Foreign Office and Sharon Hayes’ Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds. Why have you been drawn to the speaking or re-speaking these histories, and the use of the human voice? This is something that we definitely see in your own works, particularly with the Television Confession series.

I’m interested in the potential of respeaking, the power of repeating things that have already been said and how it can serve as a force in directing us towards the re-examination of discourse that might have previously gone unexamined. That’s why I picked out the works of Sharon Hayes and Bouchra Khalili.

At this point, I think it would be apt for me to quote the artist and my friend, Ho Rui An, and his thoughts on discourse. In attempting to present danger to a discourse, Ho says, the solution isn’t to simply provide a counter narrative. Any major entity, such as a state, can provide an effective rebuttal to that. Instead, one should present an image.

In my case, this would be an image of speaking, which encourages the viewer to simply look and listen. I believe that simple acts such as looking and listening can produce a quiet force that can be rather subversive and powerful. This is what I’m trying to achieve in my work.

I believe that simple acts such as looking and listening can produce a quiet force that can be rather subversive and powerful.

⁶ Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) Screeds #13, 16, 20 & 29, Sharon Hayes 2003

It’d be great if you could elaborate a little on that final idea. Why do you think of looking and listening as subversive and powerful acts?

With the Television Confession series, for example, the text that’s featured within the work are transcripts from the past. The text is just text. These transcripts were recorded some decades ago, and all I’ve done is to pick them up again. I didn’t do much to them. Within the work, these changes are minimal as well. From time to time, the person reading out these transcripts might change. They might be of a different age or a different gender, but they’re still reading these transcripts as is.

The subversive, or maybe interesting, element in this is that the work asks audiences to simply look and listen. What is this narrative that we’ve been given and accepted as truth? The idea, also, is not just to look and listen to the text once. It’s about looking at it and listening to it over and over again. Repeated listening and viewing is an important aspect of the work, and it’s quite a significant act.

With the Television Confession series, for example, the text that’s featured within the work are transcripts from the past. The text is just text. These transcripts were recorded some decades ago, and all I’ve done is to pick them up again. I didn’t do much to them. Within the work, these changes are minimal as well. From time to time, the person reading out these transcripts might change. They might be of a different age or a different gender, but they’re still reading these transcripts as is.

The subversive, or maybe interesting, element in this is that the work asks audiences to simply look and listen. What is this narrative that we’ve been given and accepted as truth? The idea, also, is not just to look and listen to the text once. It’s about looking at it and listening to it over and over again. Repeated listening and viewing is an important aspect of the work, and it’s quite a significant act.

On that note regarding speaking and respeaking, let’s move into discussing language. As a multiracial and multilingual country, it seems only natural that our historical archives reflect this diversity. Through your research and work, what are the sorts of roles that language play? Has it opened up more possibilities for you and your practice, or do you consider it a limitation?

I am bilingual, and I can read and write both English and Chinese. As such, my research at the archives is limited by this. However, I don't think that we should be surprised by the fact that we might not be able to acquire or retrieve everything in the archive. This limitation, this gap, or this absence is inherent to and part and parcel of working with archives. Instead of considering this as a limitation, I think we should begin thinking about this in a positive manner. Perhaps something that Derrida once wrote can shed some light onto this issue. In order to comprehend the identity of a thing — this can be our identity, our society or our histories — Derrida posits that we have to take its differences into account. We shouldn’t simply rely on the materials within official archives, but also question the materials that are absent. What do archives exclude from their collection?

Beyond language, there are other difficulties in working with the archive. Through my research, I’ve collected quite a few images and photographs that I’d like to use in some of my upcoming work. The images that are readily available online usually have a watermark over the top. Ordering a high-resolution version of these images, however, will cost me a couple of hundred dollars per image. Instead of thinking about this as a limitation, however, I’m approaching this from another perspective. I’m going to use these watermarked or low-resolution images as a comment on archiving.

I don't think that we should be surprised by the fact that we might not be able to acquire or retrieve everything in the archive. This limitation, this gap, or this absence is inherent to and part and parcel of working with archives.

⁷ Student Reconstruction (Television Confession), Green Zeng

2018, Video Still

⁸ Student Reconstruction (Television Confession), Green Zeng

2018, Video Still

2018, Video Still

⁸ Student Reconstruction (Television Confession), Green Zeng

2018, Video Still

Earlier in your response, you touched on the gaps within institutional archives and it’d be great if we could expand on that a little further. As someone who’s spent a significant amount of time with archives, what are some of the noticeable gaps you’ve noticed within these collections, especially in terms of how they narrate our histories?

I’ve been told that my work touches on the notion of absence quite a bit. It’s not just about what we have, but what we don’t.

With my Public Assembly series, I wanted to explore collective gatherings aimed at voicing dissent. For the most part, these gatherings have disappeared from the streets of present day Singapore. Why this absence? I think of absence and presence as two sides of the same coin. I hardly think of them as singular entities, apart from one another. When they come together, they provide a complete picture and can shape how we view a particular issue.

I’ve been told that my work touches on the notion of absence quite a bit. It’s not just about what we have, but what we don’t.

With my Public Assembly series, I wanted to explore collective gatherings aimed at voicing dissent. For the most part, these gatherings have disappeared from the streets of present day Singapore. Why this absence? I think of absence and presence as two sides of the same coin. I hardly think of them as singular entities, apart from one another. When they come together, they provide a complete picture and can shape how we view a particular issue.

I think of absence and presence as two sides of the same coin. I hardly think of them as singular entities, apart from one another.

With works from the Television Confession series, viewers experience an uneasy yet certain relationship between emotions of dissonance and resonance. The work creates questions around categorical “truths'' that one might have previously held up as definitive. Given this context, what is the place of truth or truthfulness, or does the concept of truth even matter?

To answer this question, we have to go back to our earlier discussions around Foucault. To, Foucault truth could be used in modifying power relations.

In the context of my practice, how can I touch on these ideas within my work? There are so many narratives that we might have accepted at face value, without much critical thinking or questioning. I’d like to encourage the audiences to look, listen, and reconsider these truths.

⁹ The Character, Candice Breitz

2011

With some of the works you’ve picked out, and your own recent works, the role and place of education emerges as a central theme. Could you tell us about why you’ve developed an interest in education systems and in working with students?

I would like to work with a wide and diverse range of participants across all of my collaborative projects. However for certain projects, working closely with a specific group of people can give us insight into how our perspectives around narratives and situations are formed.

With works such as Student Reconstruction and Students’ Confession, I wanted to work directly with students. I wanted to examine the ways in which we learn and absorb information or knowledge.

When it comes to the Singaporean student, there is often this impression that the Singaporean student is an effective and efficient reader of texts. I wanted to dig deeper into this, and to explore just how efficient or effective these students were. Would they recite text in the way they would with a textbook? Would they critically examine or question what they were being asked to read?

I wanted to examine the ways in which we learn and absorb information or knowledge.

¹⁰ Artist-led Workshop for Public Assembly series

¹¹ Artist-led Workshop for Public Assembly series

¹¹ Artist-led Workshop for Public Assembly series

Tell us about your experience working with these students, especially in relation to the simplistic idea that a stereotypical Singaporean student just regurgitates information without criticality.

Let’s take the work, Students’ Confession, as an example. Without giving away too much information, we asked a group of students were to read some text from a teleprompter. The students were also told that we’d ask them some questions about the text after they’ve read it. When audiences watch Students’ Confession, they’re seeing these student encounter the text they are reading for the very first time.

As these students read from the teleprompter, I think the camera was able to pick up on subtle reactions. After they read these texts, we asked them what they thought these transcripts were about. Most, although not all, the students would give textbook answers. After providing them with further context, most of their perspectives were shifted and their responses changed.

Re-enactment is a device that features prominently across your recent projects. Why have you been drawn towards re-enactment as a way of breathing life into the archive and its materials?

Within my artistic practice, using re-enactment as a device or conducting workshops are recent additions. I’m interested in re-enactment and workshops as a tool for critical thinking. I’d like to encourage participants to discuss and rethink certain events or certain truths.

I think re-enactment can also serve as a rather productive strategy when it comes to thinking about our future. A common misconception about my practice is that it is preoccupied with history. In fact, I see my practice as dealing with questions around our future.

A common misconception about my practice is that it is preoccupied with history. In fact, I see my practice as dealing with questions around our future.

By offering a re-imagination of our histories, re-enacting past scenarios can help to reframe and reposition one-dimensional or official narratives. Thinking about the past also beckons thought about what’s ahead. Would you consider re-enactment as a productive tool or strategy in imagining a way forward?

Earlier, we spoke about Foucault’s thoughts on fiction as experiments in truths, and I’d like to come back to that. It is key to this question. Fiction has some fidelity to the present, but it allows for creativity in terms of interpretation. In a way, re-enactment is fiction. You’re formulating a narrative based on the past and in reality. The question, then, is how do we deal with this reality, and how can we effect change in the future?

I see archival materials such as historical newspaper transcripts and photographs as a starting point when talking about the present. They allow us to explore possibilities for the future as well. To me, the past, present and future are one. It always comes back to looking closely and listening deeply.