James Jack is an artist who has created socially engaged works for the Setouchi International Art Festival, Busan Biennale Sea Art Festival, and Institute of Contemporary Art. His works have been exhibited at TMT Art Projects, TAMA Gallery, and Beppu-Wiarda Gallery. He was an artist in residence at the Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, Ku Art Center, the Vermont Studio Center and holds a PhD from Tokyo University of the Arts. Now he is an Assistant Professor of Art at Yale-NUS College in Singapore.

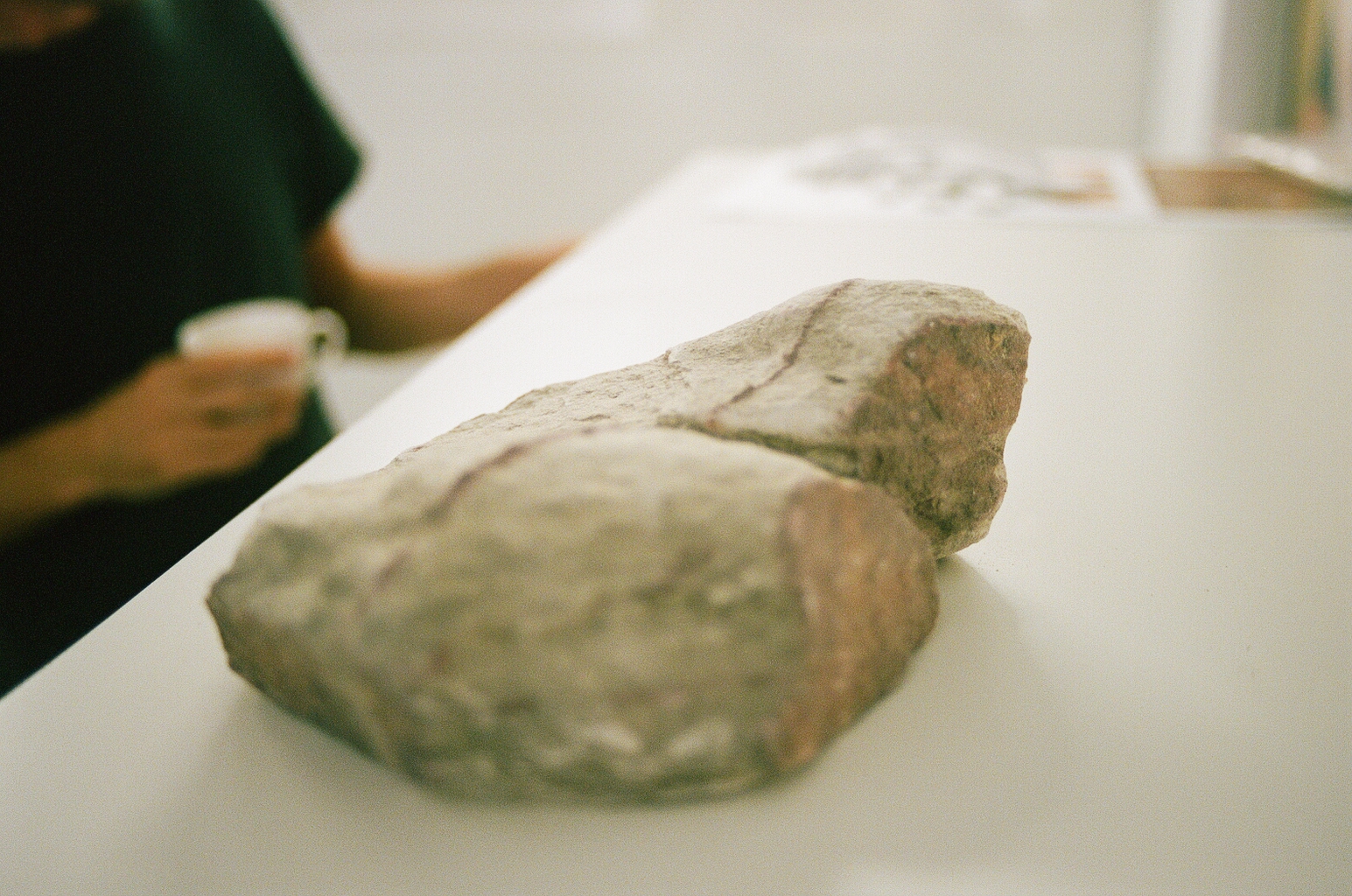

We meet with him in his studio to discuss his recent works, exhibitions and upcoming projects. To begin our conversation, James pulls out two pieces of rocks that were found on Sisters' Island. The two rocks are connected by a single line that runs through them both.

We meet with him in his studio to discuss his recent works, exhibitions and upcoming projects. To begin our conversation, James pulls out two pieces of rocks that were found on Sisters' Island. The two rocks are connected by a single line that runs through them both.

¹ Stones Enroute to Khayalan Island

What drew you towards picking out the pair of rocks as the starting point for this interview?

These stones were found on a trip I organised while in residence at NTU Centre of Contemporary Arts (CCA). I had already started with rumours of Khayalan [Island] beginning with personal memories of those who were being displaced from islands, for example not being able to tap the water from their wells or grow their bananas.

Two years later, I did a small boat trip with ten people. Each of them was selected based on their interests and background, I spoke with each of them like you and I are now, one on one. I asked them about a variety of things — what they loved doing, and what their approach to the world was. One of the participants on the trip was a sound artist, so he wanted to be absorbed into the soundscape [of the place]. He wanted to be listening, recording, and writing memos about the audio experience surrounding going to the island. Each person on the trip had a different role. Another participant on the trip, Serene, wanted to look for alternative modes through which we could understand space. Her role was one of map-making. There were some maps we looked at beforehand, but we intentionally didn't bring any of them on the boat trip.

This was one of many trips. On another trip, we used a photograph made by a seven-year-old child as a map. His image served as a guide while looking for the island. That image was published in the book Place.Labour.Capital., and was displayed at CCA last year, along with a poem read aloud and played back on speakers.

On this trip, Serene was particularly interested in looking for ways through we could understand geography or space. There was one point in the trip where seven or eight of us were gathered on rocks at low tide, facing the island of Balakan Mati. The surface upon which we were standing was almost as big as this studio, and all of the rocks were pale blue-ish in colour with maroon lines cutting across them. Some were intact, and other were broken apart. We were walking on them, looking at them, and everyone had a different reaction. Some people wanted to touch [the rocks], and others wanted to just sit around them. Serene's feeling was that these rocks were a map for how to look for Khayalan. She felt that they were an important clue, so she selected these two rocks and said that they had to always be placed side by side to preserve the line that connects them both. That's how the objects came into my studio.

After the trip, we all took turns with the objects, circulating them one by one in this way. This was to see what could be found through a circulation of memories amongst multiple people. I have exhibited alternative maps, texts and images in relation to Khayalan Island since then; but [these objects] still lie in between exhibition and process. I'm considering what they could mean in the future, but it's still a question mark.

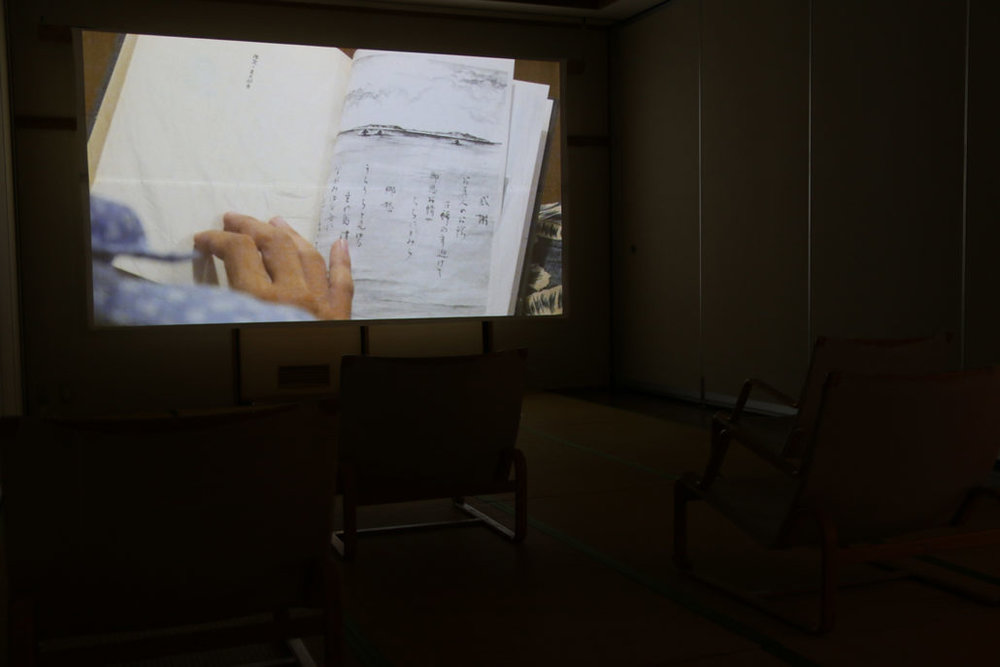

² The Disappearance of Khayalan Island, James Jack

2015, Still from a multi-channel digital video installation

Photograph from the artist

³ Khayalan Island Artifacts, James Jack

2013, Installation View at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

Photograph from the artist

2015, Still from a multi-channel digital video installation

Photograph from the artist

³ Khayalan Island Artifacts, James Jack

2013, Installation View at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

Photograph from the artist

The circulation process saw objects, such as this pair of rocks, being passed on from one person to another over a period of time. Tell me more about the circulation process, and how that came about. Why was that important to include as a facet of the project?

Memory is something that, at least in the case of rumours, is something that is collective. You can't have a rumour if one person keeps a memory to themselves. A rumour is something that's shared between people, and it changes when it's being passed on through different oral histories.

I'm interested in undocumented — or in some cases undocumentable — stories.

In this case, it was a rumour. By circulating the objects from one person to the next, I'm hoping to reconnect with things that would otherwise be impossible to find.

I have a photograph here of the National Library Board's search page, which shows the dead end one comes to when trying to look up "Khayalan Island". This was done March 12th 2015, which was a few days before we took the boat trip. I put the name of the island into the search engine, and there were zero hits. More recently, about two weeks ago, I did the same thing at the National Library of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur. Again, zero hits. This is where the process of re-imagination kicks in— what was not in the library or what could not be found in the national archives had to be found, instead, through people's stories and their collective memories.

The Khayalan Island work incorporates sources that are part of a larger oral tradition. Why work with something such as folklore or hearsay, which can be notoriously hard to pin down? How do you include something as difficult to grasp as that in your works?

The term "folklore" is rather loaded, and the term "hearsay" has a negative nuance to it. I specifically use the word "rumour", because it refers to something quite common. If you were to talk to a friend tomorrow about a rumour you heard from me today, that situation would feel quite ordinary. I like to start with moments like that, or moments that appear ordinary, and to scratch beneath the surface to reveal the deeper histories behind them. It started with a simple term, but I wanted to look for the complexity behind that.

The reason why I choose to do that is because these stories hold a lot of meaning, and can serve as lessons for people to learn from today. In standardised education, the past is approached with a lot of blindspots, along with an agenda that we're not always aware of. These different oral retellings, highlight issues that we need to pay more attention to. I'm not trying to cover all the issues that haven't been included — that's an impossible task. I just choose individual stories to represent the fact that there is much more to history. It could be an island, a story, or someone's way of seeing the world — but I intentionally select a viewpoint that isn't included in mainstream accounts of a place.

How did you come across the rumour surrounding the existence of Khayalan Island?

I was visiting Pulau Ubin quite often and around the same time I heard a talk by Venka Purushothaman, who's at LASALLE [College of the Arts], about the power of rumours.

He spoke not just on rumours, but also about whispers — things that you could barely hear but were still there.

On Ubin, I spoke to one particular farmer for quite a while. We recorded some parts of the conversation, and I never used it for exhibition but occasionally I include the audio in artist talks. The farmer told us about the disappearance of sampan (small boat), then we went to go look at one of his boats. He told us about how the boats were made of durian wood but now he can’t even grow bananas as they are cut down by authorities. Then he also brought us to a well on the island. The well was padlocked, we spent some time looking at the well.

I felt voices wanting to come out of the well. I didn't know what they were saying at that point in time, but it felt like it was really important. It almost felt as if the well wanted to break out of the lock and say something.

It wasn't until I was on Saint John's Island with Bani Haykal, the sound artist later, that I realised the well was saying, "Khayalan… Khayalan…". It was on Saint John's that I realised what the rumour meant, but on Ubin, that locked well was when I first heard a voice that wanted to be free.

How do you make sense of something like that? This experience, if you were to relate it to someone, can seem like a crazy occurrence that's been completely unheard of. What is it about the translation process — between taking that experience and placing it into an exhibition space — that allows the experience to exist in a different manner?

For example, The Disappearance of Khayalan Island and The Appearance of Khayalan Island are in the same room, but you can't see them at the same time. In The Disappearance of Khayalan Island, Andi speaks. He lives on Pramuka Island, and fixes boats for a living. This video is the beginning of the story of Khayalan. Time is not chronological, it is about giving these memories a corpus in the order that they want to be told.

Was it a curatorial decision, or was there a reason why you decided to display them across from each other in a way that almost hides one from the other?

Both myself and the curator, Masahiro Ushiroshoji formerly of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, decided that The Appearance of Khayalan Island spoke more towards the future possibility of the island appearing. On the other hand, The Disappearance of Khayalan Island was more personal. We wanted people to see that one-on-one, so we put it on a TV monitor. It's hard to see it in a big group of people. With the fishermen here and Andi [in The Disappearance] — everything's filmed with a much more panoramic view, so we decided to emphasise The Appearance in a large-scale projection.

Something else I observe is that a lot the works that you create echo the geography and history of the location within which they are exhibited. Why is that local history something you feel significantly informs your work, or is that something that comes almost naturally for you?

It is important to respect both the local and the wider audience in the works. Deciding what's shown where is always a careful balance, because the participants and the audience are both important. It's done sometimes consciously, and sometimes unconsciously — but the materials used in some of my works can be very restrictive, and that determines how far the materials can travel from one place to another. Also spiritually and artistically, some things translate into certain venues and some things don’t. You can pick up something in one place, bring it to another, and it could still have meaning or lose it altogether. I tend to shy away from taking the same work and showing it in many different places. There are always adjustments and decisions that need to be made based on the unique aspects of the exhibition space. This could be simple things, such as lighting and layout; to more complex things, such as local protocol for the borrowing of objects. Sometimes the material determines [whether or not a work can be exhibited somewhere], but other times it comes down to something spiritual. Some things cannot be removed from certain places. For example, the rocks from Sisters' Island will never leave Singapore for me. I've never brought them to Japan. I kept them with a friend here for three years while I was in Japan. It's also important that I don't possess any of these things. I just borrow them. For exhibitions, the things that are displayed have to have a relationship to that place — whether it’s an obvious one, or a subtler one. It depends on the particularities of the exhibit, but there's always a relationship.

With other artworks, sometimes I use relationships intentionally between centre and periphery. When you put objects or stories from the periphery into a museum, it sends an intentional message to audiences who often think they live in the centre. The stories or the materials I choose sometimes show them that they might not necessarily be in the centre as much as they think they are.

Do viewers then come up to you to comment on the fact that they've never considered the disconnect between centre and periphery? For example, I had never heard of the existence of Khayalan Island before coming across your work. It comes down to what you said with regards to seeing Singapore as a centre, whilst being blind to the periphery.

When you deal with an audience that fixates itself with its position as the centre and they encounter a history or geography that isn't particularly mainstream, what are the challenges that come to your mind or have surfaced in the display of your work?

It is hard to speak about the audience in an abstract way, but I can speak about people through actual concrete reactions that I've heard recently.

At my current show in the Honolulu Museum of Art, Moloka‘i Window, a parent brought their child to see my exhibit. The show works with dirt, and the main piece on display is a window painted with local dirt pigment from Moloka‘i Island, gathered with a community leader named Malia Akutagawa. There are a lot of drawings and sketchbooks within the exhibition, with quotes from community leaders and activists on the walls. This child came with her father, and got really excited about dirt and making drawings. She went home, got four or five kids in her neighbourhood, and they went and collected various dirt samples — red, black and brown. Then they painted their bodies and sticks with lots of different colours. They were probably mixing the soil with water and doing hand painting, and the father snapped a photograph and shared it with us. We need to learn from kids: adults are not the center. That was one of the reasons why I made this exhibition. Audiences got a chance to re-experience their neighbourhood as a colourful, beautiful place full of stories and earth.

Another reaction, which was a week or two ago, was from a friend who co-directs the organisation Sust-‘āina-ble Molokai. She went to visit the exhibition with a friend who doesn’t know much about art. She wanted to share Moloka‘i Window with a friend because she had been involved in the entire process. There's the aloha ‘āina spiral here that she contributed to, enlarged on the opposite side of the wall to face the window painted with dirt. You can't see the spiral and the window at the same time, but they're very closely related. Her friend didn't understand the work at all. She was like, "What's the deal? Dirt? I don't get it. Where's the artwork?" They talked about how art wasn't just the appearance of landscape, portraits, etc for quite some time. The friend wasn't easily convinced, however when they left together, her friend was no longer saying this wasn't art. Her friend just had a lot of questions, and it became more of an open-ended conversation with the idea that what is art and what isn't art is a lot bigger than she had imagined.

Tell me more about Moloka‘i Window.

The process started with small sketchbooks I kept while listening to people's stories about ‘āina, the land and their love for it. Ten years ago when I was living in Honolulu, I went to visit Moloka‘i Island. At the time, a movement called Save La‘au Point was actively resisting the actions of a tourist development company. This was a big turning point. A lot of movements were against the military, against developers from Canada — they were really fighting against those who were trying to encroach upon their land rights. After Save La‘au Point, the conversation turned towards what they were for, being pro-sustainability, pro-local culture, reviving fishing ponds and taro farms. The focus really turned towards what the local people wanted to have in the place of these big companies coming in from the other islands or other places.

I would spend about four to five hours with each person talking stories, and then ask them if it’s ok if I touch the earth there. While we were talking, I would touch the earth and make a small sketch — with no water, just the touch of my fingers, the colour of the place where we stood. If they weren't comfortable with it, I wouldn't make a drawing. There were no photos, no videos and no audio recordings of these conversations — just those drawings. The drawings were how I recorded people's stories and their connection to the ‘āina.

A few years ago, I was talking with Healoha Johnston, curator at the Honolulu Museum of Art. Of course, the stories of the people living on Moloka‘i Island were always really important and meaningful, but at this moment we felt like people actually had a lot to learn a lot from these stories. We felt like it was no longer just a personal thing, it was also about social justice. Media coverage on rural areas was really negative. They would insinuate that the residents were lazy, and their numbers always stack up really low in terms of housing and labour. Uncle Walter [Ritte] told me something, which was a piece of wisdom, that there were two economies. There's one that all of those people are measuring, and then there's the barter economy — which they actually live on. He said, "When I go out and hunt a deer, I cut it up and give it to all my neighbours. Then, they give me taro, and others trade beer". This positivity is what we wanted to share with urban communities in Honolulu, and the rest of the world.

This window is [made of] two different dirt samples. One is from maika‘i, or the ocean side, of the island; and the other is from mauka, the mountain side of the same area. The final work was painted together with three other artists and about twenty community college students, who had come to help over a period of ten days. Each brushstroke was one breath, we painted little by little from the centre spiralling outwards.

⁴ Moloka‘i Window, James Jack

2018, Installation View at the Honolulu Museum of Art

Photograph from the artist

2018, Installation View at the Honolulu Museum of Art

Photograph from the artist

Do you see some of your works as some kind of alternative archive of what people live through?

I'll leave that up to you. You can call it as you wish.

Something else I notice is that a number of your works have been made with communities. Many artists really hate it and actively shun that sort of collaboration. Is that something something that comes conveniently because of how the nature of collecting stories is like?

With Moloka‘i Window, the people on the island work on trust. Once you establish trust with someone, a relationship is possible. If you come to the island without establishing trust, Moloka‘i will chew you up and spit you out. They have something amazing called the Moloka‘i Process, and if follow that both spiritually and physically you will be protected. Recently, there was a Russian luxury yacht that tried to land on the island. The locals have a system called "Coconut Wireless" to protect the island. Coconut Wireless signals went off, and people went out in the kayaks to form a huge U-shape around the harbour so the yacht couldn't dock there. They told the yacht to go to somewhere else instead, because they didn't have the facilities to service this boat. They didn't have gas stations for a boat of that size, or fancy restaurants. The island only had one or two hotels as well, and even then they're quite small. That's just one example of what can happen when you go to Moloka‘i and try to make something that isn't in touch with the wisdom of the people.

There are also personal aspects to my work in addition to the community process. When it feels right, I go with it. When it doesn’t, then I stop. This work was just a personal feeling for five or six years. It wasn't art — it was just a feeling of injustice that I couldn’t forget. I felt the injustice between the islands, and honestly I didn't think it was possible to make an artwork for many years. I read local newspapers a lot and kept in touch with people on Moloka‘i, but it wasn't until quite a bit later that I started to see that an artwork could facilitate dialogue towards justice towards the island. Not to say this work would correct all that has been done, but the artwork could help people to meet. Malia taught me the value of ho‘oponopono. This is when groups that have antipathy, aggression, violence in the past who have been resistant to meet with each other, hold ho‘oponopono to make amends with each other. When the exhibit opened, she found the window as a space for this deep healing. Amending hatred by reconnecting people is an important part of the exhibit.

⁵ Sea Birth 3, James Jack

2018, Studio work in progress

2018, Studio work in progress

I wanted to talk to you about Sea Birth as well. I found it really interesting that a single fragment of wood from a shipwreck in the 19th century could lead into a three part series.

The object didn't lead to the whole project, rather I discovered the object along the way. There were three things that started this work: the journals of my great-great-grandfather, also named James Jack, who was a scribe on the boat they emigrated on, keeping all the maritime records. They included details on who passed away, how much food was left, and what was going on the boat. My grandfather gave me those journals before he passed away. I was reading those when I went to Tokunoshima Island, where my partner was born. We were talking to her great-uncle a lot, and he's full of folk stories and songs. During this trip, I met a local archaeologist, who had just finished an exhibition in Okinawa on underwater heritage. A lot of the ships that came through those waters came from Europe, so he's been cataloguing these ships, their purpose, and their coming and going. This subverts a lot of the Japanese colonial histories of Okinawa. This archaeologist was rewriting the history of Okinawa from the perspective of the ocean, and it told a story of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, as an interconnected archipelago. It could have been connected to my ancestors leaving Europe, and was certainly connected to various ports around Southeast Asia. This narrative is very different from the nationalised narrative told today in Japan. The fragment of wood into the project about a year or so after these discoveries.

The thing that fascinated me about this particular shipwreck was that they still knew very little about it. He had recovered some objects from the shipwreck, but they had no idea where they were from. All they had found were a couple of paragraphs in the local oral records, which states that people had swam from the shipwreck to what is today called White Beach. We recreate part of this in the film, it's a really long distance. When they landed at the beach, the locals said these people didn't speak the same language. It doesn't say where these people were from, but they were probably Western [based on nail fragments from the shipwreck]. There seemed to have been a few Chinese people on the boat who could write in characters, so they wrote on the sand, and that's how the two sides realised that they weren't enemies. The records then say these people were sent back to their home countries, and although it doesn't record where these countries were, it also mentions that presents came from those countries for many years back to the people there. That is history told through the memories of the people. For exhibits, I include an object from the actual boat, a handmade drawing of the islands and a video as one.

⁶ Sea Birth: Part One, James Jack

2017, Installation View at Museum of the Sky

Photography by Haruka Iharada

2017, Installation View at Museum of the Sky

Photography by Haruka Iharada

When you speak about the nationalist manner with which Japan has been constructing its national identity, how does reconstructing something fictionally challenge a narrative that seems unshakeable?

If the goal is to validate diversity, you can identify each object, where they're from, identify who was on the boat, and what was happening at the time to prove that Japan is not of a single ethnic origin. Rewriting textbook history is a task historians such as Amino Yoshihiko have done, and is very important, but what I'm interested in is not the placement of these objects within a pre-existing historical structure.

I think, artistically, what we need to do is re-imagine the structure itself — not just the parts that we put into the framework.

It's not that we've decided to switch some books out on the bookshelf. It's about rebuilding a whole new bookshelf — in a different shape, with the shelves and the screws being re-arranged differently. That's what I'm after. What the viewer does with the books is up to them. I suggest other books that tell different stories from the textbook version, and oral histories that could enhance those shelves.

The objects that I include in Sea Birth aren't meant to function as proof, although they appear a bit like that because I used archaeological techniques to display objects so they appear like facts. What I'm after is not telling a story through facts, or evidence-based logic. I think that logic is headed in the wrong direction. Objects have a life of their own, they have their own stories, so when people share them with another person, that sharing feeds into what I'm trying to accomplish: objects as instigators for new experiences of our surroundings. If the exhibit focuses too much on the object with facts such as — this fragment is from 1876, or this was from such and such port near Liverpool — that will tell a certain kind of data. Although I find selections of that data interesting, what I find more exciting is when we don't have dates or locations for these objects. If we don't yet know who made them, or why they were exchanged, then the viewer is empowered to make connections in their own imagination.

Each object was made by a craftsmen, and was shared with someone else. Money may have been exchanged, but more likely it was bartered for and then the object was passed on to someone for them to hold, package, and care for it; then it was passed on to someone else who put it in their room for two weeks; after those two weeks it was given over to a captain who tried to fit the object in his luggage but it didn't fit, so he gave it to one of his assistants who was on land; and as the assistant on land took it home, his wife didn’t like it so he decided to give the object to someone else and so on — every object has this very personal touch to it and that is why it still exists, what I want to do is to try and reimagine some of those personal connections. The objects are important, but they aren't the end of the line. They're just points in a web.

You're done with the first two parts of Sea Birth now, and are working on the third and final part. When you started working on Sea Birth, did you start out wanting to do a three part series?

Not exactly, but I had a strong feeling that I wouldn't be able to do what I wanted to do in one artwork. I knew that one exhibit, or one video, or one drawing was not going to capture it. While I was making the first part, I had a stroke of inspiration where I knew this was going to be a three-part series. I wanted the work to be about birth, but I knew that starting with birth would be the worst thing to do — so I started with death. The first part is all about death and spirits because there are a lot of war memories [tied to the land]. Okinawa was the only land battle fought between the US and Japan in World War II— so I knew I had to deal with death. The second part is a love story combined with hints of the military occupation of the islands that still exists up till now. Sex and violence overlap in a way, not intersecting like in Hollywood, but reacting to each other in a complicated relationship. For part three, all of the footage has just been shot, and I am currently making drawings in relation to it, but the objects have not been selected yet. The third part is about birth. The Oura Bay is a very deep bay that is rich is coral and marine life such as sea turtles and dugongs. The bay is ecologically diverse and rich, and I spent about a week there with an activist in a village called Wakage no Ikari, which translates to something like “youthful angst”. It's an amazing little community.

While we were there, we did a lot of filming by the ocean. Near the Oura Bay is Henoko, which is trapped in the middle of the Futenma Air Base's controversial move from the city of Ginowan in the southern part of the Okinawa. The northern part of Okinawa is natural and rural in comparison and this base location has been in the works by the U.S. military since 1966. At that time, Okinawa was still under US control, and the project would have reclaimed the whole harbour in front of fishing village including the Henoko River. They've moved it slightly towards the Oura Bay, which is deep enough for large navy ships to come in and out of. They want to divert ships towards this new base instead of going to White Beach, for instance, because it is also too close to densely populated areas. What this does, though, is to perpetuate post-war policies that ignore the local people by retaining over 80% of the bases in Japan in Okinawa Prefecture, while the islands are less than 1% of the total land area in Japan. I hope that artworks can expand the scope of the struggle to bring justice for the environment, Okinawan people and the sea.

⁷ Sea Birth: Part Two, James Jack

2017, Installation View at Ikei Island Taira Historical House

Photograph from the artist

2017, Installation View at Ikei Island Taira Historical House

Photograph from the artist

Although this work is connected by the overarching theme of birth, have your ideas shifted throughout the process: from when you first started out doing the first part up till now?

Yeah, definitely. The structure of each part was vague and abstract — I just knew that the story couldn't be told through one perspective, so the narrator in each of the three parts is different. The locations have been kept to the Pacific side of Okinawa, and that's an intentional choice, but the specific locations have all been different. I also collaborate with young artists, who assist, but end up making a lot of artistic decisions about the work. There are these decisions that happen along the way that can only happen in that place and time. I trust people, place, and intuition to guide the way.

For example with the first part of Sea Birth, the plan was to shoot on Kudaka Island, which is quite famous for its shamanist traditions. It's a beautiful island — there have been a lot of films made about the area, and a lot of anthropologists spent a lot of time there. One local filmmaker's father was from there too, so when we went there it just didn't feel right to film and make an artwork about the place. Instead we spent a lot of time there, talking to people and walking around the place — realizing it wasn't the right place to make the work. It turned out that Tsuken Island and Ukibaru Island were the places to tell the stories of the spirits of Kudaka, without doing it in a direct way. I am not just making a documentary or making my work about a place — it was about the spirits in between islands, the people and the sea. We had to follow the spirits wherever they guided us.

One of the days, we were meant to get onto the boat to Kudaka. There was a huge typhoon that came into town, and we couldn't get onto the boat. My friend said that we were probably not meant to go, that this was a sign. We spent the night on land instead, and we spoke more about literature, songs and activism. The next day we went to Kudaka, but we didn't shoot or make any artworks. We spent time there, and recognised this as a really important part of the process, but the birth of the sea had to actually happen in the sea. Then I started working with a diver named Tamae Masayuki, and the first part of Sea Birth is narrated by him. His memories guided us to the places where we filmed.

I notice that you talk a lot about respecting spirits, and there is a certain spirituality that factor into your work such as intuition. Has that sensitivity to the spiritual always featured in your work?

That is a hard question to answer. Once you hear spirits, it's really hard to not hear them, so it's hard to say when they started.

My early works were interested in natural materials, places, and definitely alternative ways of understanding space — but I was a bit afraid of going headfirst into the spirit world of voices, and ghosts.

For a long time, I've been making my own inks. Boiling inks has an alchemy to it, and people have built religions based on alchemy.

It's not an organised religion, and I wouldn't put a name on it — but I think that spirits have a larger purpose for me, my work and my audiences. The older I get, the more I allow that to just be what it is. I don't make work only about spirits, but I weave them into a tapestry, allowing them spaces to say what they want to say.