On 5 October 2018, Jenny Saville made history when her work, Propped, sold at Sotheby’s for £9.5m ($12.4m). However following the furore of Banksy’s self-destructing painting, media outlets around the world glossed over Saville’s monumental achievement quickly.

To bring attention back to Saville, we decided to pull together a selection of ten of her greatest works. Known for her unflinching and honest depictions of the female body, Saville’s works first caught the eye of art collector and gallerist Charles Saatchi. Saatchi bought most of the works Saville produced as an art student, and included her works in the 1997 exhibition, Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Gallery.

To bring attention back to Saville, we decided to pull together a selection of ten of her greatest works. Known for her unflinching and honest depictions of the female body, Saville’s works first caught the eye of art collector and gallerist Charles Saatchi. Saatchi bought most of the works Saville produced as an art student, and included her works in the 1997 exhibition, Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Gallery.

“I never questioned my ambition. I never thought: I’m a girl, I can’t do this. It was only when I got to art school that I realised that the great artists of the past were not women. I had a sort of epiphany in the library: where are all the women? Only then, as the truth dawned, did I start to feel pissed off.”

— JENNY SAVILLE¹ Plan, Jenny Saville

Saatchi Gallery, 1993

Saatchi Gallery, 1993

Saville works on large canvases, using them as the background for voluptuous and fleshy bodies. The canvas she used for Plan measures 2.74m x 2.135m. When hung, Saville’s portraits often overwhelm the viewer with their sheer size and visceral clarity.

Plan was painted in 1993, shortly after Saville graduated from the Glasgow School of Art, where she was a student between 1988 to 1992. Saville depicts the woman looking down at the viewer, and almost confronting the viewer with an unfiltered perspective of her crotch. It marked, in many ways, the tone of the works she would continue to produce for quite a while.

![]()

In this painting, she marks out the contours of the female body in a manner reminiscent of topographical maps and marks made on a body prior to liposuction. After graduating and painting this work, Saville spent long hours observing the work of a plastic surgeon in New York. The time she spent sitting in on these surgical procedures helped to form her perspectives towards the flesh and body.

Plan was painted in 1993, shortly after Saville graduated from the Glasgow School of Art, where she was a student between 1988 to 1992. Saville depicts the woman looking down at the viewer, and almost confronting the viewer with an unfiltered perspective of her crotch. It marked, in many ways, the tone of the works she would continue to produce for quite a while.

In this painting, she marks out the contours of the female body in a manner reminiscent of topographical maps and marks made on a body prior to liposuction. After graduating and painting this work, Saville spent long hours observing the work of a plastic surgeon in New York. The time she spent sitting in on these surgical procedures helped to form her perspectives towards the flesh and body.

“It’s all things. Ugly, beautiful, repulsive, compelling, anxious, neurotic, dead, alive Eventually we expel ourselves. We rust away. Our own body rejects us. I don’t find that tragic.”

— JENNY SAVILLE

² Trace, Jenny Saville

Saatchi Gallery, 1993 - 1994

Saatchi Gallery, 1993 - 1994

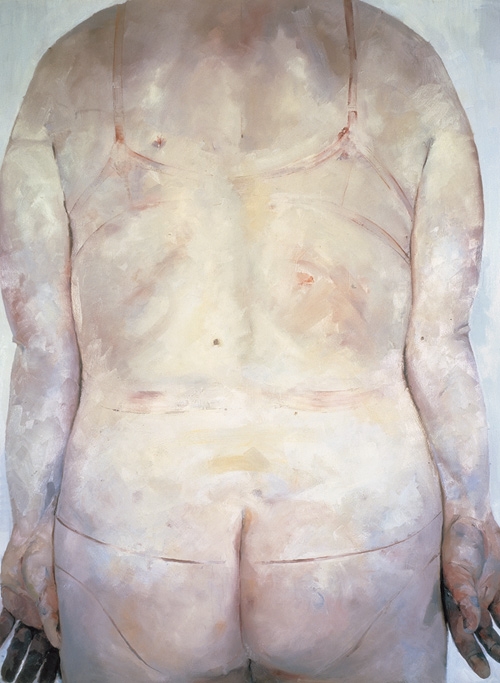

Trace is another early work of Saville’s. In this painting, the body fills up the entire canvas, squeezing excess blank areas on either side out. Only the figure's torso is kept in the frame, and Saville cropped the head and legs out of the composition. The resulting portrait is one that is, literally, larger than life. The perspective of this painting is unassuming — with the figure’s back turned to face us, the viewer.

![]()

Clothes and undergarments leave their traces on the body, their outlines sinking into the figure’s skin. These impressions on the figure’s body hint towards the pains of being a woman, thereby allowing a subtle yet dulling ache to seep into this depiction.

This painting was recently featured in the National Gallery of Scotland’s exhibition titled Jenny Saville, Sara Barker, Christine Borland, Robin Rhode, Markus Schinwald, Catherine Street.

Clothes and undergarments leave their traces on the body, their outlines sinking into the figure’s skin. These impressions on the figure’s body hint towards the pains of being a woman, thereby allowing a subtle yet dulling ache to seep into this depiction.

This painting was recently featured in the National Gallery of Scotland’s exhibition titled Jenny Saville, Sara Barker, Christine Borland, Robin Rhode, Markus Schinwald, Catherine Street.

“I’ve always cared more about a work being powerful than being beautiful. And beauty scared me, I would say. I was afraid that if it was beautiful, it wasn’t serious or it was sentimental or something like that, that terrified me to go in that direction.”

— JENNY SAVILLE

³ Reverse, Jenny Saville

Gagosian, 2003

Gagosian, 2003

Many of Saville’s works are depictions of herself, and one such example of this is Reverse. Here the artist is portrayed lying down, with her head tilted to meet the viewer’s gaze. Despite modelling this painting after herself, Saville does not see this image as a self-portrait per se, but as reflective of something deeper within — a “neurosis”.

![]()

This is a marked shift from her previous works, where pale blues and purples dominated. Here, the colour palette used gives the impression of congealed and crusted blood. Deep reds and warm brown hues are centred and thickened, in particular, around the figure’s mouth.

This work was first exhibited, alongside a series of newly painted works, in the 2003 exhibition at the Gagosian titled Migrants.

This is a marked shift from her previous works, where pale blues and purples dominated. Here, the colour palette used gives the impression of congealed and crusted blood. Deep reds and warm brown hues are centred and thickened, in particular, around the figure’s mouth.

This work was first exhibited, alongside a series of newly painted works, in the 2003 exhibition at the Gagosian titled Migrants.

“I wouldn’t make this work if I was a guy.”

— JENNY SAVILLE

⁴ Passage, Jenny Saville

Saatchi Gallery, 2004

Saatchi Gallery, 2004

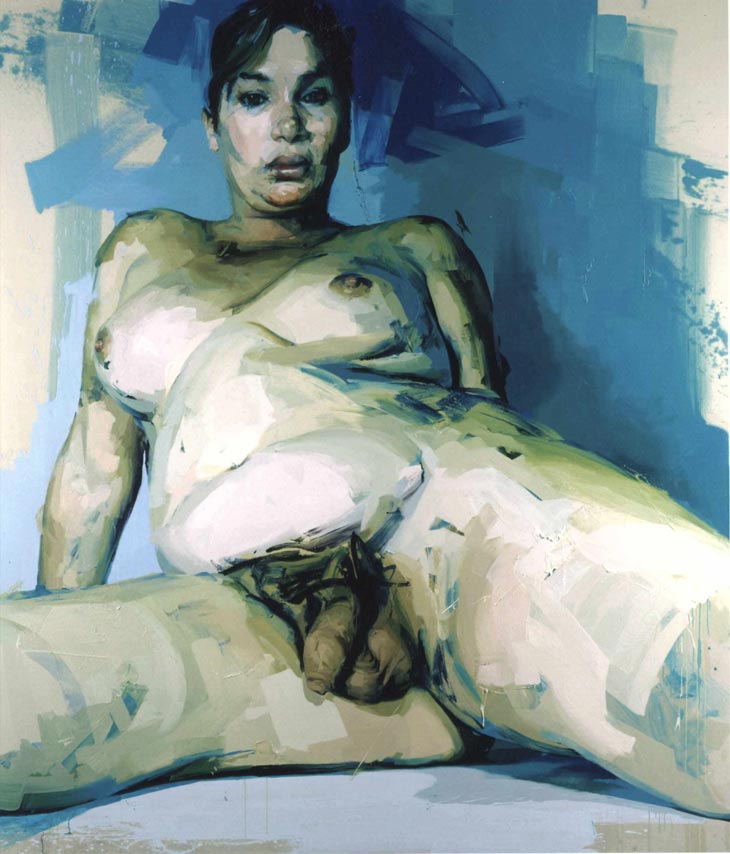

Saville’s works are not confined to portrayals of the cisgender female body. Interested in “a sense of in-betweenness”, Saville is intrigued by transsexuals and hermaphrodites. These figures in these paintings are raw and unapologetic, and run contrary to how art has historically rendered hermaphrodites.

![]()

“With the transvestite I was searching for a body that was between genders. I had explored that idea a little in Matrix. The idea of floating gender that is not fixed.

— JENNY SAVILLE

The transvestite I worked with has a natural penis and false silicone breasts. Thirty or forty years ago this body couldn’t have existed and I was looking for a kind of contemporary architecture of the body.

I wanted to paint a visual passage through gender – a sort of gender landscape.”

⁵ Red Stare Head IV, Jenny Saville

Gagosian, 2006 - 2010

Gagosian, 2006 - 2010

Saville’s works have also graced the cover of music albums. A rendition of this particular work was used by the Welsh rock band, Manic Street Preachers, for their album, Journal for Plague Lovers. The album cover drew criticism as audiences thought the figure’s face was bloodied and injured.

The distortions of the human figure and face have been integral to Saville’s practice, and this work explores similar thematics. This episode raised questions as to how art was consumed or displayed, and if art could only interrogate in the “safe space” of a gallery.

This was not the first time Saville’s work had been used as an album cover design. The same band had previously used another work of hers, Strategy (South Face/Front Face/North Face), on the cover of their album, The Holy Bible.

![]()

The distortions of the human figure and face have been integral to Saville’s practice, and this work explores similar thematics. This episode raised questions as to how art was consumed or displayed, and if art could only interrogate in the “safe space” of a gallery.

This was not the first time Saville’s work had been used as an album cover design. The same band had previously used another work of hers, Strategy (South Face/Front Face/North Face), on the cover of their album, The Holy Bible.

“I am quintessentially figurative. I am rooted in figuration and actually, maybe picture making is not figuration.

— JENNY SAVILLE

I am a picture maker, I’m an image maker.

Even if I start completely abstract, which I do often — just throw loads of paint on a canvas — my instinct, my animal instinct is to make something of it you know not to let just have paint sensation but to make an image.”

⁶ Reproduction drawing II (after the Leonardo cartoon), Jenny Saville

Gagosian, 2009 - 2010

⁷ The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and John the Baptist, Leonardo da Vinci

National Gallery London, c. 1499–1500 or c. 1506–8

Gagosian, 2009 - 2010

⁷ The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and John the Baptist, Leonardo da Vinci

National Gallery London, c. 1499–1500 or c. 1506–8

Drawing upon Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and John the Baptist, Saville created a series titled Reproduction. The series’ title has two meanings, the first being the process of artistically copying one’s work, and the second being childbirth.

Her love for art history was kindled by her uncle, who was an art historian and an artist. Saville often reaches back into Western art history to question the male gaze inherent in so many of these works, and what this means for artists today.

Saville often works from photographs, and requested that a friend photograph the process of her giving birth. She referred to these images whilst creating this series.

![]()

![]()

This drawing shows Saville and two babies — one in her arms and the other in her womb — and are contemporary interpretations of the archetypal mother and child.

Her love for art history was kindled by her uncle, who was an art historian and an artist. Saville often reaches back into Western art history to question the male gaze inherent in so many of these works, and what this means for artists today.

Saville often works from photographs, and requested that a friend photograph the process of her giving birth. She referred to these images whilst creating this series.

This drawing shows Saville and two babies — one in her arms and the other in her womb — and are contemporary interpretations of the archetypal mother and child.

“Motherhood has also taught me to cut the crap. I used to come in and make coffee, read the paper, have lunch. Time was fluid and I probably wasted it. Now I come in, take off my coat and start.”

— JENNY SAVILLE

⁸ Ebb and Flow, Jenny Saville

Ashmolean Museum, 2015

Ashmolean Museum, 2015

Motherhood changed the way in which Saville viewed her art, her practice, and the time she spent making art. Whilst watching her children “going crazy on the kitchen floor with paint”, she embarked on a long period of experimentation by “going outside the lines and multiplying the lines”.

![]()

“Just because of the transparency of drawing, you’ve got the possibility of multiple bodies. It’s an attempt to make multiple realities exist together rather than one sealed image.”

— JENNY SAVILLE

⁹ Aleppo, Jenny Saville

2017 - 2018

2017 - 2018

Aleppo was first exhibited at the National Gallery of Scotland as part of the exhibition titled Jenny Saville, Sara Barker, Christine Borland, Robin Rhode, Markus Schinwald, Catherine Street.

![]()

Saville owns an extensive collection of war photography, and observed that despite their varying contexts, many of these photographs show soldiers cradling injured children in their arms. She referenced those images when painting Aleppo, which is a searing portrayal of the realities of war, and drew parallels to the art historical archetype of the pieta.

Saville owns an extensive collection of war photography, and observed that despite their varying contexts, many of these photographs show soldiers cradling injured children in their arms. She referenced those images when painting Aleppo, which is a searing portrayal of the realities of war, and drew parallels to the art historical archetype of the pieta.

“A lot of images of war situations and they’re so remarkably similar whether they’re Rwanda, whether they’re Bosnia, whether they’re Iraq, Syria, you know that’s maybe the colour of skin and the physiology changes a little bit, but the basic impulse is the same and we do this again and again as humans.

— JENNY SAVILLE

We just blow buildings up, we kill each other, we have children that are dying in our arms and you sort of think, gosh, we’re like, we just repeat this cyclic pattern.”

¹⁰ Vis and Ramin, Jenny Saville

Gagosian, 2018

Gagosian, 2018

The title of Saville’s 2018 work, Vis and Ramin, draws from the 11th century Persian poem of the same title. In the medieval Persian telling of the story, Vis and Ramin are star-crossed lovers.

![]()

Here, Saville experimented with plastic wraps and abstracted forms, creating a work that fused both classical bodily forms and abstracted painterly styles.

Here, Saville experimented with plastic wraps and abstracted forms, creating a work that fused both classical bodily forms and abstracted painterly styles.

“You can almost have a figurative and abstract painting exist in the same picture, without it being a conscious movement between abstraction or figuration.”

— JENNY SAVILLE

¹¹ Red Fates, Jenny Saville

Gagosian, 2018

Gagosian, 2018

In a recent solo exhibition titled Ancestors at the Gagosian, Saville revisits tropes, themes and myths that have come to be synonymous with Western art history. In particular, the work Red Fates references the Fates (Moirai). The Fates are figures within Greek mythology that controlled the destinies of all living mortals.

![]()

In this painting, three women sit alongside each other, each in a different position of repose. These works continue to showcase Saville’s interest in portraying the female form, but push the boundaries by including bold slashes of blood red paint. These violent eruptions interrupt the otherwise intimate and quiet depiction, alluding to the powerful and terrifying control the Fates have, as myth goes, over the lives of humans.

In this painting, three women sit alongside each other, each in a different position of repose. These works continue to showcase Saville’s interest in portraying the female form, but push the boundaries by including bold slashes of blood red paint. These violent eruptions interrupt the otherwise intimate and quiet depiction, alluding to the powerful and terrifying control the Fates have, as myth goes, over the lives of humans.

“It’s an incredible journey in my life to now sit between those Titians and have a dialogue and to see ok, I’m doing this and how does my work look in that context?”

— JENNY SAVILLE

“I don’t even know my own collectors. All the razzmatazz: the market, the auctions. I’m quite immune to it. I know it’s part of the process. But when you get in the studio, none of that will help you to make a better painting.”

— JENNY SAVILLERELATED PUBLICATIONS:

1. Adams, Henry Brooks, Richard Shone, Lisa Jardine & Martin Maloney. Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection. London: Thames & Hudson, 1997.

2. Calvocoressi, Richard and Mark Stevens. Jenny Saville. New York: Rizzoli, 2018.

3. Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson, 2012.

4. Elderfield, John. Jenny Saville: Oxyrhynchus New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2015.

5. Marlow, Tim. "A Conversation with Rubens: Tim Marlow Interviews Jenny Saville RA", Royal Academy of Arts, 20 March, 2015. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/jenny-saville-tim-marlow-rubens.

2. Calvocoressi, Richard and Mark Stevens. Jenny Saville. New York: Rizzoli, 2018.

3. Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society. London: Thames and Hudson, 2012.

4. Elderfield, John. Jenny Saville: Oxyrhynchus New York: Gagosian Gallery, 2015.

5. Marlow, Tim. "A Conversation with Rubens: Tim Marlow Interviews Jenny Saville RA", Royal Academy of Arts, 20 March, 2015. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/jenny-saville-tim-marlow-rubens.