Jeremy Sharma (b. 1977, Singapore) obtained his Master of Art (Fine Art) at LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore in 2006. Jeremy Sharma works around ideas of aesthetics and production, merging visual art and music. His practice investigates various modes of enquiry in the information age, addressing our present relationship to modernity and interconnectivity in the everyday and our place in an increasingly fragmented and artificial reality.

As part of the Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. exhibition at the ArtScience Museum, Jeremy is exhibiting a work titled Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues). The piece is a half hour long sound installation, and is a narration of excerpts by Marie Darrieussecq, Haruki Murakami, Virginia Woolf and Ludwig Wittgenstein. For our interview, the artist picked out the works of Gerhard Richter, Roberto Chabet, On Kawara, Alberto Giacometti, Joseph Beuys, Tetsuo Miyajima, Janet Cardiff and Taryn Simon — all of which were influential to creating this piece.

As part of the Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. exhibition at the ArtScience Museum, Jeremy is exhibiting a work titled Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues). The piece is a half hour long sound installation, and is a narration of excerpts by Marie Darrieussecq, Haruki Murakami, Virginia Woolf and Ludwig Wittgenstein. For our interview, the artist picked out the works of Gerhard Richter, Roberto Chabet, On Kawara, Alberto Giacometti, Joseph Beuys, Tetsuo Miyajima, Janet Cardiff and Taryn Simon — all of which were influential to creating this piece.

¹ 4900 Colours, Gerhard Richter

2007

When you sent your selection of artworks over to me, you actually categorised them into these little headings:

Richter and Chabet’s works as “Painting Objects”

Miyajima and Beuys’ work as “Environments”

Cardiff and Simon’s work as “The Human Voice”

Giacometti and Kawara’s works as “Time and Space”

Why did you feel it necessary to group these works up under headings, and what about these works jumped out at you whilst conceptualising Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues)?

I think it helps me to break down and shape how I think about an artwork or an object, and how it then relates to my own practice. All of these elements relate to my work. In thinking about this interview, I was trying to think about specific objects but I couldn’t. So I started thinking about artworks that have inspired me, and of course there have been many. I had to narrow them down specifically, and hence the compartmentalisation.

Specifically with Richter’s 4900 Colours, I saw it at the Serpentine Gallery in London in, maybe, 2007. It was quite a couple of years back, but it still stays in my memory. What I like about it was the experience of viewing his exhibition — both as individual paintings, and the ideas behind the entire exhibition. It was a very perceptual experience. When you look at 4900 Colours online, the colours look very flat. It looks very mosaic, and is reminiscent of pixels. But when you experience that object in a space, it becomes very different. The work looks almost industrial, but I think they were painted or sprayed on by hand. Richter would have, of course, had his assistants to help him with this work. But the execution of the work was so meticulous that it got me thinking about painting conceptually, as compared to painting as something that had to be done expressively. I had always known about Richter’s works, but it’s always nice to see his works in the flesh. I was familiar with his blurred photo paintings, his abstract series, and his colour chart series. Seeing it in the Serpentine Gallery was also a surreal experience. The galleries are surrounded by green spaces such as forests and parks. Coming into the gallery, I wouldn’t describe it as a spiritual experience, but it was a pure experience of paint and colour. That got me thinking about the phenomenological experience of a painting, and I applied that to some of my works — especially my grey paintings. In a way, it wasn’t about being minimalist. It was about an idea, and materialising an idea — and yet, it is a physical.

² To Be Continued, Roberto Chabet

2011, Installation View at Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore

A common gripe that many viewers have with modern and contemporary art is its shift away from the figurative towards the concept. As an artist working across a variety of mediums, how do you decide which medium will best convey your concept to the viewer?

I see myself as an artist-at-large, so I think a lot of it is about decision making. I’m not medium-specific, as of now. I wouldn’t say that I’m entirely concept driven — I am drawn by the medium and by its materiality. Sometimes, the medium comes first. It could be painting or the human voice. With the artworks that I’ve selected, I think the medium plays a very strong role. They aren’t floaty conceptual pieces because there is a strong sense of materiality in these works. With any of the artists I’ve chosen here, I think it really comes down to the idea of translation.

With a previous exhibition I did at Aloft by Hermès, fidelity, I just had this idea of working with songs and the human voice. So that came first, really. In order to create the work, I knew I had to get up close and personal with communities. Travelling and doing fieldwork then became very important in creating that authentic experience. It’s not about appropriation, in that sense, but about learning firsthand from the people around you.

Coming to Chabet’s work, it’s another piece that’s quite conceptual. Chabet is one of the pioneering conceptual artists in Southeast Asia, and compared to Richter, he works on a very different platform. There was a 2011 exhibition of his works done at the Institute of Contemporary Art Singapore in LASALLE, and I think it contributed towards creating much needed discourse around understanding Chabet’s work and Conceptualism in Southeast Asia. With Chabet’s work, the viewer knows it relates to metaphors and symbols, but these concepts are very simply manifested. Even without reading into the work too much, one can still get a sense of what Chabet is trying to say. Some of his works relate to Russian Constructivism, or to the sea and the pier. In comparison to Richter’s work — which is more cerebral — I find Chabet’s work a little more playful and more everyday.

When it comes to my work, there isn’t a clear answer as to what comes first.

Sometimes the idea comes first, but the material needs to be strong enough to carry that idea through. Other times, it’s the other way round.

If I’m working with the voice, I could work with a computer voice. Instead, I choose to work with the firsthand experience of recording. I think the experience of being in a recording studio is important. Working with people I’m familiar with is also important, because I’m familiar with how they speak. For Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues), I worked with friends and I liked the timbre in their voices.

With my Terra Sensa series, where I translated the signals of dead stars, I wanted to work with foam because it was lightweight yet durable. It is an everyday material used for packaging, and it suggests insulation. I wanted that sort of sensibility in the work. Also, foam is cheaper than wood. It is not as heavy as wood, which makes carving on it much easier. It is durable, but it looks fragile. You wouldn’t expect an artist to be using a material such as polystyrene foam.

³ fidelity, Jeremy Sharma

2018, Installation View at Aloft at Hermès

Photography by Edward Hendricks

2018, Installation View at Aloft at Hermès

Photography by Edward Hendricks

⁴ Forty Part Motet, Janet Cardiff

Tate, 2001

![]() ⁵ An Occupation of Loss, Taryn Simon

⁵ An Occupation of Loss, Taryn Simon

2011, Installation View at Park Avenue Armory

Tate, 2001

2011, Installation View at Park Avenue Armory

You picked out Janet Cardiff’s work for this interview, and she once described sound as allowing her to work with memory in the way that she wanted to.

Having worked with sound and the voice on previous works, such as fidelity, before, how have you seen your understanding of the human voice as an artistic medium develop?

I was particularly influenced by the writings of Roland Barthes, especially in The Grain of the Voice. He spoke about the voice being embodied, and as a pre-linguistic material signifier. When we hear someone singing, we might not always understand or hear the lyrics. Yet somehow, we can tell if its melancholic or energetic because of the way the tune sounds. The song could come from a place that is familiar, or a place that is foreign.

The human voice is something that is both embodied and disembodied at the same time. When you record a voice, it’s very different to the act of taking a photograph. Taking a snapshot is quite violent, and it cuts away a scene without giving the sense of anything outside of that frame. On the other hand with voices and recording voices, you have to be there listening. You have to take the time to figure out what’s being sung. There’s the part where you’re recording, but there’s also the part where you listen to the recording again at home. It’s a very different experience hearing the voice without the body, and it can be quite strange. You might even pick up things that you hadn’t heard previously because in that moment, you might have been observing something very different.

Listening to the voice again, it becomes a very different material — something that you use to collage, piece together and layer on top of another sound.

Your work, Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues), is in the “Colour” room at the ArtScience Museum’s Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. exhibition. Colour is something that many would associate with a visual experience, yet you’ve approximated that with sound instead.

In previous conversations, you spoke about wanting to challenge yourself in working with sound. Now that the work is installed, how do you see the relationship between something as visual as colour, and something as invisible as sound?

I wanted to work with perception, which is non-visual, through the act of listening, through fiction and memory, and through reading. This work came to me through reading first. I think of reading as a multi-sensorial experience. When you read, you imagine the world the book describes. It is abstract in the sense that despite us both having read the same book, my imagined world could look very different to your imagined world. To me, the sort of mental images one gets from reading is very interesting. I wanted to allow for those sort of experiences in the context of a room. It is akin to listening an audiobook, and the process of beginning to imagine what is being said. That’s a form of non-visual perception.

The act of listening is rather sensorial in that it activates a very different sense. At the same time, it’s not abstract. The work is composed of two actors talking about colour. The script comes from books — books that have been written by actual persons. It’s quite layered, actually. When you’re listening, there are different levels of inter-subjectivity. The first layer comes from the two actors, because they’re reading with their own voices. However, they’re reading from a script that has been written by me. The script, in turn, comes from books that have been appropriated for this work. These books were written by different authors at very different periods in time. Some of these authors are literary writers, and others are philosophers. When these come together, it becomes a very different reality. It becomes quite uncanny — it is either strange or familiar. Imagine if the script had been read by children instead. It would have made for a completely different experience.

One of the two actors has a very strong New York/Buffalo accent. He’s been living in Singapore for many years, but he never lost that accent. The female voice belongs to a Singaporean. The two actors sometimes sound like they’re having separate monologues, yet at other times it seems as if they’re talking to each other. The sound is spread across the room through five different speakers, and I wanted to keep it very low key. I realised that the louder the sound was, the muddier the voices became. It didn’t make sense in the exhibition because there was a lot of reverb in the space. I wanted to make the piece as soft as possible. Somehow the softer it was, the more audible the work became.

I also played with gaps, pauses and silences in this work, so that what was absent could still be felt. When there’s a long pause, the moment where a voice comes in again then becomes more meaningful and more poignant.

It is similar to taking a breather, taking a break, or thinking. Much like reading, most of us don’t read an entire book in one sitting. You take a break, and then you come back.

It’s the act of reading, the act of speaking, the act of listening, and the act of being in that space. It’s so different listening to the work through your phone or your MP3 player. It’s a distinct experience being in that room, having it correspond to other works in that space, and seeing it form relationships to these other works. It becomes a very spatial experience.

⁶ Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues), Jeremy Sharma

2018, Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. Installation View at ArtScience Museum

Photography by Marina Bay Sands

2018, Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. Installation View at ArtScience Museum

Photography by Marina Bay Sands

The script for the piece is based off a couple of texts by Murakami, Woolf, Darrieussecq and Wittgenstein. How were the texts chosen and interspersed with one another?

The basic criteria for the texts was that they had to talk about colour. As I began to read these texts, I realised that although these texts discussed colour, they were also texts about other things. The readings are quite diverse, and they came from recommendations and my own research. As I was reading them, I was making notes and underlining certain sentences. I wasn’t sure if it’d flow well in the form of a script, because the prose was so disparate. I’m not sure if it has been entirely successful as well. In order to come up with the final script, I did a lot of listening.

It is quite interesting when different passages from different books link up together because of similar themes. That’s visual, in a way, because in visual art, you’re looking for elements that work together as well. Here, I tried to create a work that would work textually and sonically.

⁷ Plight, Joseph Beuys

Centre Pompidou, 1985

⁸ Mega Death, Tatsuo Miyajima

1999/2016

Our experience of hearing your work is visually accompanied by the works of Donald Judd, Carmen Herrera and Chen Shiau-Peng. Were these works, and the relationship Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues) would have to them, always at the back of your mind when you were creating this piece?

No. In initial conversations with the exhibition curators, I thought I would be exhibiting a previous object or painting within the space. The conversation soon evolved and turned towards the direction my practice is moving towards. That was when the museum decided to commission a new work that would be experimentative in that it worked with sound alone. It wasn’t planned, and I didn’t know if the idea of a sound piece would work. I’d only know for sure when the piece was installed, and that came along much later in the process.

It is difficult to visualise a sound work and how it would work in an exhibition space. With a visual piece, you can sort of envision how it would sit in relation to a spatial context; but with sound, it’s a lot more fluid.

Sound works with the actual physicality of the space, so you’ll only know in hindsight if there were things that you could have done better when putting together the work. Sound works very differently.

An interesting aspect of this exhibition is probably the fact that these works were curated with the intention of placing them in conversation with each other. Seeing your work installed with the works of three other artists, have you observed these works as bringing out congruences, similarities or contrasts in each other?

One of the key elements of my work is its duration. You get a sense of time with a sound piece that you don’t really get with a static object. Duration in relation to a space creates a very different experience because one stays in the room for longer. Having, for example, Donald Judd’s piece in the room and hearing someone talk about the colour red in my work might be quite serendipitous in that what is being said connects to what you’re looking at. I think those were the sort of connections and slippages that could be drawn between the works.

Also, there is a sense that new viewing contexts have been created with this showcase. In terms of curation and exhibition making, those conversations were important to create. These artists are all deserving of their own solo shows, but putting them side by side takes them out of those silos. The curator at the ArtScience Museum, Adrian George, wanted to draw out these thematic links. The entire exhibition space itself is circular, and begins with Mona Hatoum’s + and - — itself, a circular piece. The sound piece I’ve created is also cyclical. It runs for 24 minutes, then it loops back again. That also relates to teamLab’s Enso, so there are a lot of themes that are recurring and one simply needs to pick up on these cues in order to see it all come full circle — pardon the pun.

My work was in the “Colour” room because my work talks about colour, yet it engages with it in a very unique way. Colour, in a way, is not just about form. It is also about memory, and about association. Maybe colour cannot be distilled into a state of purity. Colour relates to material — the rose is red, someone’s hair is brown. Colour is not a pure entity in and of itself. It is relational. Colour is also durational. There’s a quote by Wittgenstein where he says that what you were looking at five minutes ago could have changed — it’s not quite static. Often with the language of Modernism, it tends to seem quite static, singular, and monolithical.

⁹ Man Pointing, Alberto Giacometti

Tate, 1947

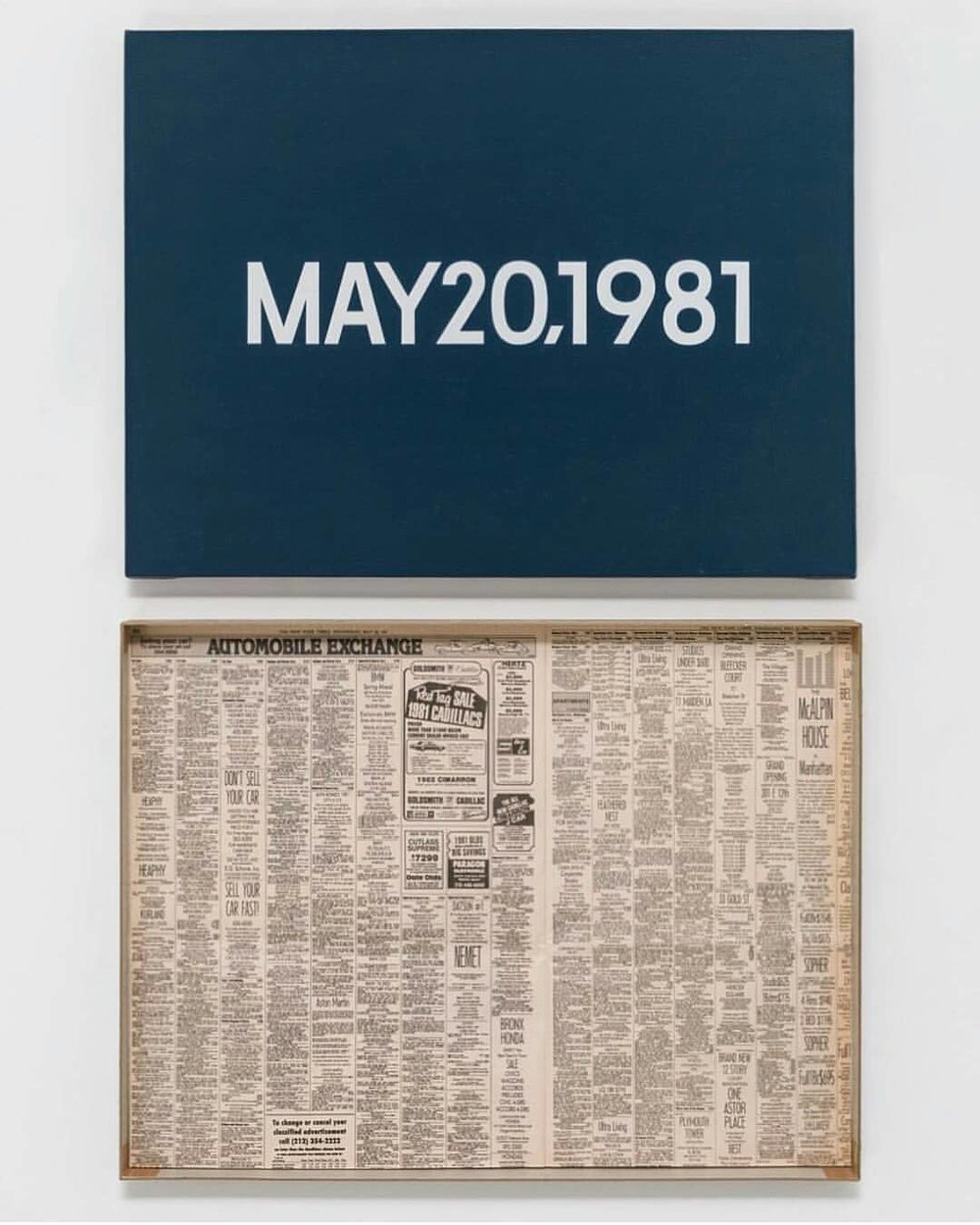

¹⁰ MAY 20, 1981 (“Wednesday.”), On Kawara

1981

In a previous email exchange, you mentioned this quote by Lawrence Weiner which states that space is the entire cultural context within an artwork exists.

Because Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues) was commissioned for this particular exhibition, do you see yourself redisplaying the work in a different exhibition or space again? If so, do you think its new viewing context will change the way or add another layer to how we understand the work?

Yeah, definitely. If I were to exhibit the work again, it would be nice for it to have a room to itself. In its current context, it is being viewed through the dialogue of Minimalism and how this Western movement relates to what we have back here in Singapore. I see it as a form of education. What you read about in textbooks can look or be understood very differently when seen in real life. In seeing all of these various artists in conversation with each other, you can see the similarities and where these similarities end quite clearly. For example, I just learnt about the Chinese Maximalist movement. Their brand of minimalism is very different to the Western art movement because their works evoke the spiritual. Although these works look similar on an aesthetic level, they have very different contexts and meanings.

It got me thinking as to where my work comes in in all of this. We’re mostly Western-educated here in Singapore, and particularly in art school, it is Western art history that is being taught. James Elkins once gave a talk where he spoke about the importance of seeing art history as art histories — in the plural as compared to the singular.

Art history is, inherently, Western. Acknowledging that is important so that we can then begin to reshape how we understand history.

So placing my work, as a Singaporean artist, into the fold, perhaps creates a new dialogue. In a sense, it is both universal and not. If you speak of the cultural context of my work, you’ll probably start to think of where I come from or where it was made. It was made locally, it was made through connections with my friends, and it was shaped by my own experiences. The script takes from books that I read whilst I was travelling and researching. When you begin to peel these layers away, you begin to uncover various aspects of the work.

The context changes with, first, the physical space. But in the context of that physical space, there also exists the space that the work creates for the viewer. The space that the work creates is, inadvertently, shaped by the viewer as well. With listening, it’s rather subjective. You can say the same about visual art, but I think with sound, what I hear will be very different to what you hear. I think that there is something about reading and listening that is quite individual. It’s not quite a shared space. Even though the sound occupies a shared space, what gets absorbed into one’s mind is unique. The viewer is shaped by their own baggage, history and memories. I won’t really know, for sure, what a person is experiencing when she or he listens to my work. I’m still waiting for feedback about the work. It’s still a fairly recent piece, so I think it needs time to really pick up.

You’ve mentioned the importance of an in person or in the flesh experience a couple of times throughout our conversation, and I was wondering if you see the work possibly going beyond the physical space and being uploaded, perhaps, onto a digital space or platform?

Yeah, it’s possible. Actually, I’m quite fluid with this. I’ve gotten over the stage where my work needs to be experienced in a particular form, so I think it could definitely work as an MP3. I would just curate it particularly for that experience — it could even be an audio tour. It just needs to be curated and thought through.

An earlier iteration of this work was shown at Sullivan+Strumpf, at an exhibition titled Spectrum Version 2.2. For that exhibition, I showed some of my light boxes along with a sound piece. This sound piece, however, was filtered through a horn speaker in the gallery. It wasn’t very clear or audible, and sounded similar to prayer calls. It was a very different experience. With the current iteration at the ArtScience Museum, I was going for more clarity. Where previously I had stereo — one speaker for each voice, I now have a surround sound system at the ArtScience Museum with five speakers. I also configured the speakers to have the voices come out from different speakers at varying intervals. I drew a diagram to help me visualise how the voice could come in.

Out of the four texts I reference, a main part of the work draws from the writings of Wittgenstein and Woolf. Wittgenstein was a German philosopher who wrote extensively about language and our perception of it. Woolf was an early Modernist writer, and a beacon for feminism as well. The two figures come from very different places. Woolf wrote in an emotive, stream-of-consciousness manner; whilst Wittgenstein had a very analytical tone about his works. In a way, placing them side by side and having that binary between a male and female writer creates a sort of tension as well. These are the sort of sub-layers that I was looking to bring out as well.

I don’t think the viewer really needs to pick out what exactly is being said either. The idea of hearing a voice in a space is enough for me. I remember going to church as a kid — used to, I don’t go to church anymore — because I was born Catholic. I used to go for masses, and the priests would always give these sermons where different readers would come up to read from the Bible. I was always interested in how people read differently, and how they interpreted these texts differently. I was listening to their voices and how they read these words, and not what was really being said. There is something calming and therapeutic about listening to someone’s reading voice. These are the sort of things that I picked up on from my own memory. I also have two young children. When my wife had just given birth, it was quite a busy time for all of us. I didn’t really have time to read anymore, so I would put on an audiobook whilst driving instead. Engaging with texts that way made for a very different sort of experience as well. When I think of my relationship to sound and how I understand it, all of these memories come back to me.

¹¹ Spectrum (Mahi Mahi), Jeremy Sharma

2017, Spectrum Version 2.2 Installation View at Sullivan+Strump

Photography by Sullivan+Strump

¹² Spectrum Version 2.2, Jeremy Sharma

2017, Spectrum Version 2.2 Installation View at Sullivan+Strump

Photography by Sullivan+Strump

2017, Spectrum Version 2.2 Installation View at Sullivan+Strump

Photography by Sullivan+Strump

¹² Spectrum Version 2.2, Jeremy Sharma

2017, Spectrum Version 2.2 Installation View at Sullivan+Strump

Photography by Sullivan+Strump

There are varying triggers for everyone, but many of us are reminded of particular memories when encountering sound as well. Did you envision this work as transcending the aural and being an encompassing multi-sensorial experience?

Yeah. Even with my previous works, I’ve always been interested in questions about interpretation and translation — because they’re not quite similar. New objects and new realities are formed when a text is read through a particular person, or with a particular voice. I find that plurality very interesting. Though it might seem quite different, I do explore similar ideas with the foam paintings in my Terra Sensa series. There, I was translating radio signals into a new material, foam. I’m using similar ideas, but in a very different manner and interpreted through different bodies. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of transmission as well.

Oral cultures are steadily declining as well. Traditionally, oral narratives and stories form the basis of many Southeast Asian cultures. These stories would have been passed down from generation to generation. We now live in a culture that is incredibly saturated with the visual, so I think it’s nice to bring that form back as well.

Spectrum Version 3 (The Monologues) is part of

Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. at the ArtScience Museum.

The exhibition is a collaboration with the National Gallery Singapore,and will run until 14 April 2019.

For more information, visit the Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. website.

Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. at the ArtScience Museum.

The exhibition is a collaboration with the National Gallery Singapore,and will run until 14 April 2019.

For more information, visit the Minimalism: Space. Light. Object. website.