Joanne Pang is an artist and design lecturer at Lasalle College of the Arts. She explores the relationships between body, memory and space through site-specific installations, paintings and drawings. She holds a BA Visual Communication degree from the School of Arts, Design and Media in Nanyang Technological University, and received an MA Fine Art degree from The Royal Danish Art Academy (Charlottenburg Sculpture Department). She is a recipient of numerous art and design awards such as the recent UOB Painting of the Year (Gold Award, Established Artist Category 2018), Singapore Young Photography Award (2012) and Singapore Design Awards (2012). She has exhibited in solo and group shows at the Singapore Art Museum, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Kilometre of Sculpture, 9th Shiryaevo Biennale of Contemporary Art, Chan+Hori Contemporary and Institute of Contemporary Arts.

Only half the year has passed us by, and Joanne has already shown her work in three group and solo exhibitions. Entering her studio, it almost seems as if every corner of the space is alive with colour. Joanne’s sunlit studio is filled with brushes, cups and canvases both complete and incomplete. Settling ourselves down on a couch, we started this interview with her selection of books by Gaston Bachelard and Georges Perec, and artworks by Walter de Maria and Yves Klein.

Only half the year has passed us by, and Joanne has already shown her work in three group and solo exhibitions. Entering her studio, it almost seems as if every corner of the space is alive with colour. Joanne’s sunlit studio is filled with brushes, cups and canvases both complete and incomplete. Settling ourselves down on a couch, we started this interview with her selection of books by Gaston Bachelard and Georges Perec, and artworks by Walter de Maria and Yves Klein.

¹ The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard

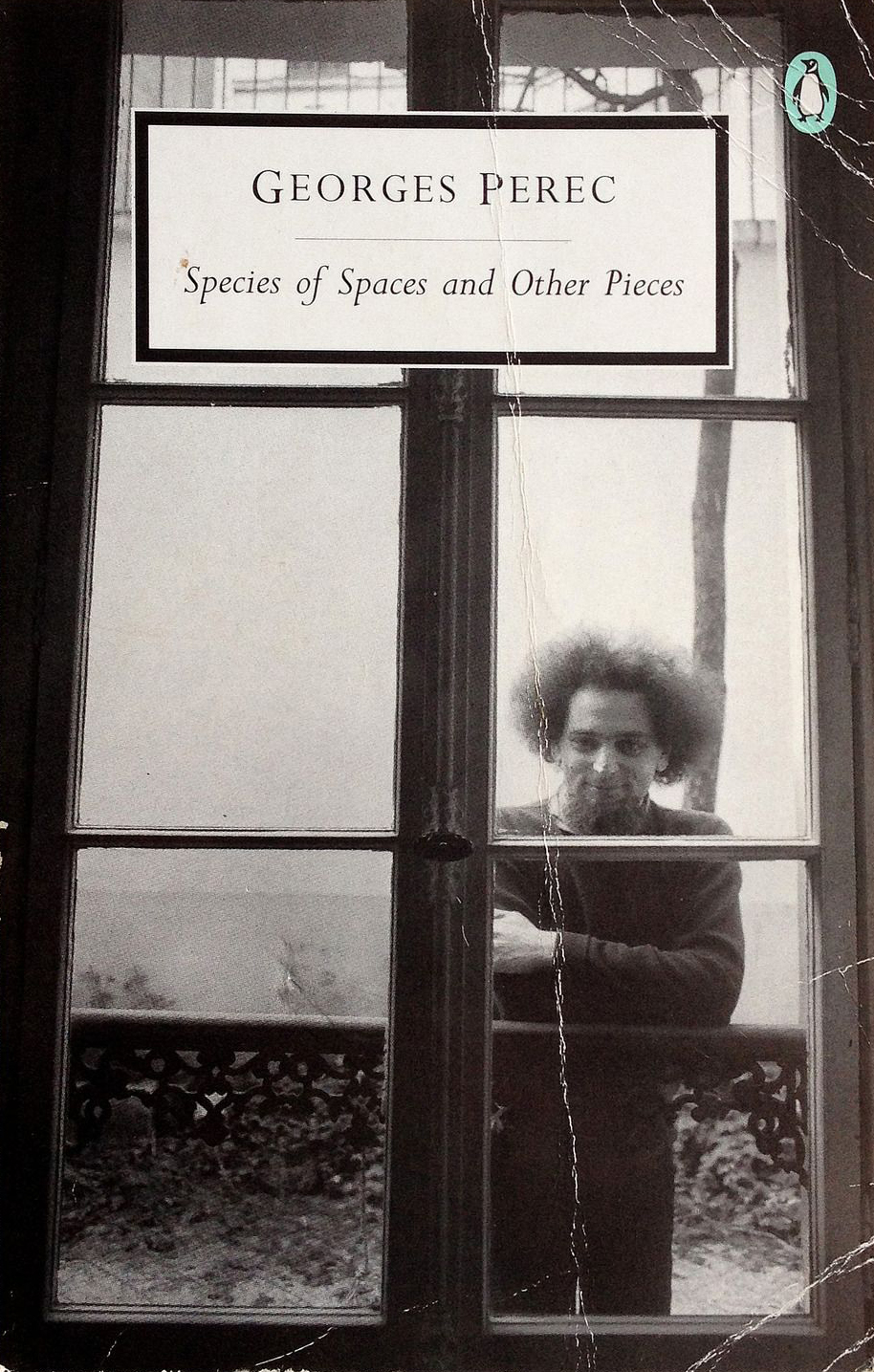

For our conversation, I wanted to begin with the two books you chose. You’ve picked out Georges Perec’s Species of Spaces and Other Pieces and Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. These two texts have been fundamental, although in slightly different ways, in reframing how we understand our personal embodied relationship with the spaces we inhabit. As someone who works a lot with cloth surfaces, what draws you towards textual sources that discuss the built environment?

These two books are important for me because of how they approach the body as a space. In The Poetics of Space, the book is punctuated by chapters such as “Corners”, “Miniatures” or “Houses”. These are spaces that we are all familiar with, but Bachelard wrote about them in such a poetic manner that I was able to see them in a completely different light. We base what we know on our own personal experiences, so when I read this text, it made complete sense to me.

In particular, I think what many readers enjoy about The Poetics of Space is how it drew their attention towards spaces that they might have otherwise overlooked.

Like drawers — exactly. The text constantly shifts and moves between the perspectives of the macro and micro as well.

I have to confess that I encountered this text when I was in the final year of my degree at the NTU School of Art, Design and Media. I was interested in the in-between spaces — spaces between people, spaces between the outside and the inside, windows, airports and more. My lecturer recommended this book to me, and I was initially a little hesitant in picking this book out for our conversation because it’s not something that I refer to constantly. It’s just something that I read almost ten years ago, but I still remember the connection I felt to the book. It allowed me to think freely and helped me to see things differently as well.

I also think that titles are so important. Although the title of this book seems simple enough, The Poetics of Space, it reveals the ambition of the book in going beyond seeing architectural spaces in relation to three-dimensional planes. I also find that connection to poetry interesting.

² Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, Georges Perec

We often understand academic disciplines such as poetry or architecture to be distinct from one another, but these books really broke down the distinction between the two. Although you encountered Bachelard’s book years ago, do you still find yourself referencing or drawing upon it because you read them during rather formative years?

Yes, particularly when it comes to drawing a connection or relationship between the human mind and these built spaces. For example if we consider a drawer, it is not just a drawer — there are so many more layers of nuance to it. It is also functions as a container for something else.

In comparison, I read Perec’s Species of Spaces and Other Pieces more recently. I used an excerpt from the book for an exercise with my students as well. When I read the book, I was particularly struck by the relationship that Perec drew between the horizontal page surface and the bed. I’m trained in graphic design, so I found that comparison interesting despite their differences in scale. The idea of horizontality speaks to me a lot because I realise that I work that way with my paintings as well.

Does this mean that you place your canvases flat on the ground and work on them from above?

Exactly. When I lie the surface flat in this manner, I find that gravity works on all corners of the canvas in equal measures. This allows the ink, paint and water to move in a more even and distributed way. It feels more fair to me. If I were to have the canvas propped up, the paint would drip down in a particular direction and that feels a little more forceful.

I always think of it in relation to how, as human beings, we find our time split between states of horizontality and verticality. I find the more upright positions we find ourselves in to be more prominent, in terms of how we make our presences known when we’re standing tall and straight.

There is always this relationship between the vertical and the horizontal not just in painting, but in everything that we see around us.

Because you work on your canvases horizontally, have you ever considered exhibiting the paintings flat on the ground as well instead of having them hung up on a wall?

Although I work horizontally most of the time, I do find that I oscillate between having the canvas laid flat and propped up. I start off with the canvas on the floor, but might stand the work up midway through to get a different look at it before lying it down flat again. There is this push and pull that makes working on a painting incredibly engaging, especially because the distances from which I work on the canvas change constantly throughout the process. I think we need an awareness of both directionalities in order to grow in appreciation for the surfaces we occupy.

³ The Vertical Earth Kilometer, Walter de Maria

Friedrichsplatz Park, 1977

Another work you picked out for our conversation is Walter de Maria’s The Vertical Earth Kilometer. It’s a really interesting work because it’s not a visible work, so to speak. It’s mostly hidden from one’s view, and if not for the devices surrounding the work that point towards it, many viewers might not have been aware of its existence.

In this I see certain similarities with your interest in time and memory, in that both of those notions can prove rather difficult to pinpoint or visualise. How have you navigated, or have certain devices helped you navigate, the seemingly stark contrast between the materiality of paint and the layers of time and memory that resist, in a way, this materialisation?

When I first started painting, I found that a lot of my work drew upon ideas of identity, and that that was somehow linked to consciousness. When I made that connection, I realised that I was a little confused as to what consciousness was or what it entailed. For example, does being conscious refer to being aware? I started doing a bit of research into this and came across some philosophical texts by Henri Bergson. The idea of memory began to interest me, because the idea of consciousness is inherently linked to what we remember. I can remember how to go back home, who my mother is, and certain faces or spaces. Memory plays a large part in informing who we are, and it is also important to note that these memories come in layers. These layers don’t always have a clear shape — they can overlap or be diffused. You could remember a feeling, for example, but you might not remember what made you feel that particular way. There is a certain power in that memory.

I started exploring these ideas first through black ink. I found the movement of the ink mimicking the different mental states that we can find ourselves in. I also work in layers, for example, in the Chinese paper that I paint on. Every experience that we have can be seen as a stain that leaves an impression upon us. Because of that, I found the use of ink incredibly apt. Through a visual work, I wanted to create this relationship between drawing and memory.

I came across The Vertical Earth Kilometer more than five years ago, and found it incredibly powerful because it’s not about what you can see. The work comprises of a single metal rod that penetrates the ground and through several layers of Earth. It no longer is just about your own experience with the artwork, but also leads the viewer to consider the artwork in relation to the ground. The work is also testament to human determination and resolve in placing structures into the ground. This also relates to my interest in architecture. When it comes to making art, it’s always great to have compelling ideas. Yet, executing these ideas is a completely separate matter. I think architecture exemplifies this synergy quite well.

This actually brings to mind a work by Robert Smithson where he poured asphalt down a mountainous terrain. I really appreciate that spill as a gesture because of how abrupt it was. It was precisely because it was abrupt that that gesture became a work of art.

When you talk about working with soaking and staining, the works of Helen Frankenthaler do come into mind as well. Are you aware of her works?

I really enjoy Frankenthaler’s work too, and I’m looking forward to seeing her works at the Venice Biennale. I had only chanced upon her works last year, and I remember seeing how she worked by pouring on really huge canvas. It was really nice.

With Frankenthaler, there’s also that sense of the process being intuitive and open-ended in how the cloth interacts with the paint. There are all of these parallels in how you both work as artists.

If I could make a comparison, I would say that the line is still very important in my work. With Frankenthaler’s work, you get these large swathes and expanses of colour. I’m interested in the connections between writing, drawing, painting, and mark making. I’m fascinated by the idea of the line, and how differences in thickness or directionality can affect our perceptions.

⁴ Leap Into The Void, Yves Klein

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1960

Coming back to what we talked about previously about action or gesture driven work, that ties in nicely to your selection of Yves Klein’s work Leap Into The Void. This work has been cited by many performance artists as inspirational or influential for its ability to balance calculated action with the impression of spontaneity.

When it comes to your work, you speak about making marks or lines on your canvas alongside pouring or staining the cloth surface as well. How do you negotiate between the more choreographed aspects of mark making and the fluidity of working with stains?

When I begin working on my paintings, I always start off with an intention. I think it’s human nature.

There’s always this pause in the beginning of my process because I’m thinking about what to do. Often, I’d spill a transparent liquid such as water onto the surface then outline its contours.

There are many different ways in which you could capture something or to freeze something in a particular time and space. Photography is a great example of this, but for me when it comes to painting, I work with outlining things such as puddles or stains of water. Apart from the initial gesture of pouring the water over the canvas, I have no control over how the water spreads or moves across the surface. I could be romanticising this, but I find that in drawing the outline of these stains, I become part of an otherwise abstract moment.

You’ve worked with different fabrics, such as silk and linen, and fluid mediums, such as Chinese ink or acrylic. Could you speak a little more as to the thought processes that you run through when selecting or experimenting with these different surfaces and mediums? Do you find that having worked with different permutations and combinations, that this knowledge now informs your intent when working on a new piece?

The whole endeavour of painting consists of play, experimentation and exploration. I use different cloth surfaces as a way in which to observe how paint interacts with different textiles. It’s similar to how we explore different spaces or travel as human beings. Why do we travel? We travel so as to get a different perspective, a new feeling, or a unique experience. Similarly, I just wanted to see how paint reacts to various surfaces so I could take that into consideration with my work.

Initially, I wasn’t attracted to working with white cloth surfaces. I’d always pick out coloured textiles for my works. At the same time, I found myself shying away from colours as well. This could be a result of my background in design, but my earlier works were made with black ink on rice paper. That could be described as being very graphic. When I began working with cloth, I was drawn to the colour of the fabric. The bales of cloth are displayed in such a manner that you see these different colours and patterns interacting with one another. The spectrum or system of colours gradually became more alluring to me, and I started working with textile surfaces that were light or pastel coloured for my paintings.

Would you then consider dyeing your own textiles in order to manipulate or control the exact base colour you’d like to work with?

That’s an interesting idea, but I hadn’t thought about dyeing the cloths myself before. There’s always something that we start off with. Even if I were to dye my own cloth, the base colour does not have to be pure white. When you take a look at my process, you could see the stains I make as a form of dyeing as well. I sometimes work with really large stains, and it can feel like I’m dyeing the cloth in this process as well. In that sense, I don’t think dyeing has to constitute soaking the entire cloth surface in a single colour.

Whether you refer to what I do as dyeing or staining, I’m trying to not get too caught up in the words themselves. It is so much more important to just create the work than to put a shape to the process through this terminology.

⁵ Enter and Echo, Joanne Pang

2019, Installation View at UOB Art Gallery

2019, Installation View at UOB Art Gallery

When you talked about your earlier black ink on rice paper works, you described them as graphic. Your background is in graphic design, and you’ve worked across sculpture and installations before as well. How have you made sense of these experiences in terms of where you’re at artistically right now? Do you see these different disciplines seeping into how you approach your practice today?

There are always aspects that are similar between the worlds of graphic and art, especially when you think about colour and form. But I think that’s just the world we live in. We’re always going to be surrounding by colour, forms, shapes, textures and lines. I think the main point of difference is in how these materials are offered up to the creative mind. In design, there’s always a creative brief. On the other hand, art is pretty open-ended.

I always found design enjoyable, but I found certain briefs to be quite limiting. It also felt like I was constantly solving someone else’s problems for them, instead of posing questions that were interesting to me. My background in design really helped me use tools, materials and elements in a distinct manner. I think communication also forms a large part of design, but at some point I began to find certain aspects of design unfulfilling. I realised this when I was doing the final year project I mentioned earlier whilst at NTU School of Art, Design and Media. With this project, I wasn’t looking to answer anyone else’s questions but my own.

We communicate with each other in words, but when you break those words down, they are primarily just letter forms. These letter forms contain the histories of writing, such as how we used hieroglyphs or how we understand signs and symbols. When I began think of design in terms of communication, it really helped me understand myself and the world around us better. In design, the goal is to be clear in the message you’re trying to communicate. In art, there isn’t always that element of communication. Sometimes even as an artist, I don’t even know what I’m trying to say — let alone expect that the viewer understands my message clearly. That’s the beauty of visual art.

I’ve also found myself being drawn to the spatial because the body needs to exist within a context and an environment. The first residency I did was in Finland, and during my time there, I didn’t work much with two-dimensional forms. Instead, I worked on site-specific installations and that felt more immediate or direct to me.

There is a real tangibility to site-specific works, and they envelop the viewer in a way that perhaps two-dimensional graphic work cannot.

It’s great when an image functions as an image. The more abstract something is, the more opportunities there are for one to form a connection to it. In comparison, we often take things such as sofas for granted. We sit on them and we have a direct encounter with it that doesn’t push us towards thinking or reimagining about its context. You’d have to think hard in order to redefine what you consider something as functional as sofa to be. With images, on the other hand, there’s always this distance.

⁶ Your Sadness is Mine, Joanne Pang

2013

2013

Prior to our conversation, you sent me an image of your work Your Sadness is Mine. It is an image, but you said that you see it more as an object right now because of how moss has begun to develop between the frame and the print. Tell me more about why you described it as such. do you draw a clear distinction between two-dimensionality and objecthood?

For Your Sadness is Mine, I used photography to capture an idea — the idea of layers. For this image, I stacked layers of wet tissue on top of each other in order to comment on how we use tissue paper to mop up excess liquid. In this work, the tissue will always remain wet and photography allowed me to freeze that moment.

I think there is more objecthood or object-ness in something as time passes. An image is quite distant, and it can feel quite mummified in the sense that it has locked up a particular time and space for all posterity. Yet when photographs begin to weather we see them more as objects, and this is particularly so with historical photographs. Somehow they become more tangible and there’s almost a heightened sensitivity about them.

I think it’s also important that we don’t get bogged down by this terminology. A photograph can be both an image and an object at the same time. I think categorisation always comes later, but the most important thing is always to create or to produce.

Categorisations are put in place for order and clarity, and this happens not just in art but in every other facet of our lives as well.

There seems to be this tension between allowing an artwork the space it needs to breathe or just exist, and providing viewers with a framework or the literacy with which to approach these works in the first place.

It’s quite sad that one’s inability to use vocabulary is seen as an impediment to them accessing an artwork. Most of the time, art should be felt.

I think sometimes we don’t help when we label artworks. I think having a title already pushes it, but I see the value in having an artwork title as well. It is a doorway into the artist’s headspace at that particular point in time. Yet at the same time, it can be something that limits an audience’s perception of an artwork too.

At the same time, you don’t shy away from using texts in exhibitions of your work as well. Your current showcase at SPRMRKT features both brochures and wall text. How have you been able to use language in a way that leads and does not impede?

Sometimes, I incorporate letter forms into my paintings as well. I might not always use text per se in my work, but it can be about the letter unit as well. For example, I could draw the form of the letter “F” into my painting. I think there are certain strokes or movements I make over the canvas that reference how I write.

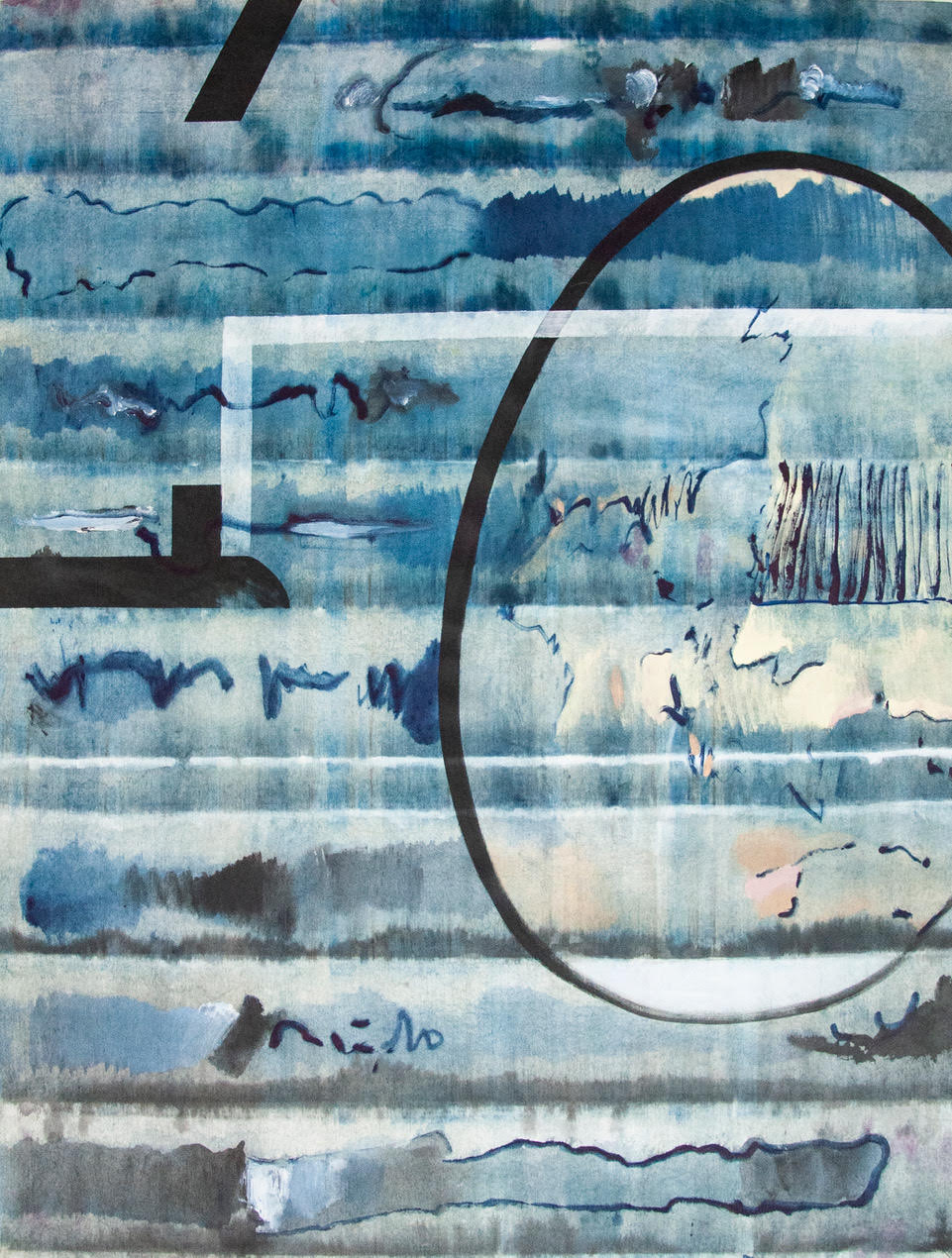

⁷ Species of Texts and Spots, Joanne Pang

2019, Installation View at SPRMRKT at Cluny Court

⁸ Murmurs, Joanne Pang

2019

2019, Installation View at SPRMRKT at Cluny Court

⁸ Murmurs, Joanne Pang

2019

On that note, I also wanted to discuss your two most recent shows. One of them, Species of Texts and Spots, is still ongoing at the restaurant SPRMRKT at Cluny Court. The other, Enter and Echo, was exhibited in the corporate space of the UOB Art Gallery. How was that experience like working with unconventional viewing environments, and did you approach both exhibitions with different strategies?

All the spaces I’ve exhibited in before have existed before me showing my works there. For the UOB Art Gallery, the quantity of paintings on display mattered to them so that was stipulated beforehand. They wanted 13 paintings in the gallery, and there wasn’t curation in the usual sense of the word. The paintings were just hung back to back in two columns, but I enjoyed the detached nature of this arrangement as well. It was very matter of fact, and it was an interesting experience having my works shown in such a corporate setting as well. When you go to an art gallery, for example, the intention is to look at art. In these spaces, often people stumble onto the gallery or the works on display. It’s not intentional, and the space is incredibly liminal.

In comparison, SPRMRKT is a dining space so there is a very close connection to the food that is being served there. Initially, I had concerns about how the smells from the kitchen would interact with the works. It was a new experience seeing my works in a non-white cube environment. There’d be furniture, people, food and smells around. The opening of the exhibition was an interesting experience because there were diners in the space eating throughout. There is a lot of distance created with the artwork as a result. On a physical level, you can’t really get up close and personal with the work because there might be tables in front of it or another customer seated right beneath a work. It creates a dilemma whereby you as a viewer might not want to intrude into someone else’s space, yet the artwork has been hung there for everyone’s appreciation.

It’s always nice to see my paintings in different contexts and interacting with different spaces and audiences as well. It’s something that I’m learning more about as well.

This is definitely a very experimentative perspective on a communal, dining experience. For customers who might walk in for food and don’t know that SPRMRKT works with artists constantly, they might just see these works as decor.

I’m completely aware of that, and that’s natural. If I were a customer, I would think it was part of the restaurant’s decor as well. In a sense, it is decor and that’s completely fine.

When you go to an art gallery, you don’t do anything when looking at an artwork. Viewing artworks in a restaurant setting means that you’re multitasking. You’re having your food, engaging in conversation and enjoying the music in the background all whilst possibly appreciating the art on the walls as well.

Your connection to the art is different because your mode of being is different.

It’s more natural, in a sense, because how often is it that we’re singularly focused on just one task at any particular point in time anyway?

⁹ STILL, Joanne Pang

2019, Installation View at Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

2019, Installation View at Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

Some of the works that you displayed at the exhibition STILL at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (ICAS) were also in the UOB POY Gallery later in the year. Do you find that your perceptions have changed, or have you heard from audiences with regard to their responses shifting, as a result of seeing the same work being displayed under very different auspices and viewing contexts?

I haven’t heard from anyone in particular, but the settings at ICAS and the UOB POY Gallery were very different. There are so many variables that differ between them. The surroundings, the mood in which a viewer would be in when they enter both spaces, and even the other works that you see in conjunction with mine — all of these factors would significantly alter one’s perception. It’s always great to show the same works in different spaces because they then begin to form new relationships with other works.

It reminds me of the movie Amélie, where the protagonist had photographs of a gnome in various places. The gnome itself remains the same, but the surroundings are constantly changing. Similarly, the art itself does not change.

Having called several cities home and knowing the artistic communities and ecosystems of various places intimately, do you think that those experiences have given you a different perspective as to how the arts and cultural scene here in Singapore is like or has developed?

I think the time I spent exploring and jumping from place to place allowed me the possibility of vulnerability and failure. I spent a lot of time not knowing what to do, and it would extend to everyday things such as not knowing what to buy or what the people around you were saying. Eventually, you learn to be okay with it because you have to live there.

The first residency I did in Finland offered me a very stark contrast to the landscape here in Singapore. It was a forested area, and the language they spoke was so different as well.

Contrast is important, because that’s how you get a real sense of difference and change.

When I was in Denmark, what really struck me was the fact that they were very knowledgeable when it came to materials. The country has a history of craftsmanship, so you’d have material-based workshops at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. It was a very traditional way of approaching a medium, but there was plenty of room for experimentation. I was also drawn to living in Denmark because of the lifestyle there and attitudes of the Danish people. My time in Denmark brought me new experiences and feelings, feelings such as solitude. In some way, those aspects became more significant to me than the academic lessons that I learnt.