Jollin Tan is a growing writer who feels most comfortable with confessional poetry, although she constantly pushes her own limits and the perimeters of her writing. Her first two poetry collections, Bursting Seams and Derivative Faith, are published by Math Paper Press. Jollin’s work can also be found in anthologies such as Body Boundaries, SingPoWriMo The Anthology, Balik Kampung 3B: Some East, More West. Her poetry has also been curated for Prairie Schooner and Singapore Writer’s Festival.

We speak to her about how she's developed from her two published volumes of poetry, Bursting Seams and Derivative Faith. Both volumes were published in 2013, when she was only twenty years of age. Five years on, the poet finds herself navigating very different waters.

We speak to her about how she's developed from her two published volumes of poetry, Bursting Seams and Derivative Faith. Both volumes were published in 2013, when she was only twenty years of age. Five years on, the poet finds herself navigating very different waters.

¹ Whip, Zoë Croggon

Daine Singer, 2016

² Nu Rose, Raoul Dufy

Musée Unterlinden, 1930

You've chosen three artworks here, and they're all really different pieces. Why were you drawn to choosing them out for this interview, and what about them drew you in?

The context for this is that I have a running list of artworks in my phone. When I see works of art in galleries, I note down their names in my phone. Sometimes when I see artworks, I don't always immediately know how to feel about them or what to feel about them. I often feel like I need to know more about the works, so I note their names down and then run a Google search later.

When you asked if I wanted to do [an interview for Object Lessons Space], I was looking through the photographs on my phone for artworks that I wanted to talk about. I didn't want to just bring a poem to the table — it would have been very typical of me to do that. I also don't think I can talk about poems objectively because I'm very whiny about the ones that I like, so I didn't want to do that.

That's also why I chose a couple of photographs. Actually, one is a collage, another is a photograph and the final one is a painting. The three works aren't really linked, for me, in any specific way. They all just have this incredibly understated look. Whip by Zoë Croggon is just a collage of two images. Bruce Davidson's photograph shows a group of people in a car having a break. Raoul Dufy's painting is an ugly nude — not to insult Raoul Dufy because I love his works, but I think I'm very attracted to art that's not trying to say something huge. I don't know if it could be applied to all of them, because obviously the painting was tackling big ideas that were present in the 1920s. It came out of a period of time termed New Objectivity, so that's another thing altogether.

³ Teatime In The Car, Bruce Davidson

Magnum Photos, 1960

Tell us more about New Objectivity.

I saw the photograph, Teatime In A Car, at a photographic exhibition at the Barbican. The exhibition was titled "Strange and Familiar: Britain as Revealed by International Photographers", and it was being shown next to some photographs that were being done in the New Objectivist period. I don't think this photograph itself could be included under the umbrella of New Objectivity — it strikes me as more of an editorial photograph as Bruce Davidson's background was in editorial photography. In a lot of his interviews, he spoke about looking for narratives; and hence his works don't fall comfortably under the same category as Raoul Dufy's painting. But there were a bunch of photographs exhibited in the gallery where the concept of New Objectivity was brought up. It was an entire movement of artists and photographers who were trying to give attention to the everyday and the banal, as opposed to what had come directly before — which were the Expressionist and Impressionist movements.

These artists took a new lens to the idea of objectivity. They didn't approach it the same way, perhaps, realists might have done it. Instead, the method by which they approached their art gave their works more context. A lot of painters who were aligned with this movement tried to depict subjects as they looked, whilst considering their social status and the kind of roles these subjects played in society. As such, Dufy's nudes can be seen as rather subversive. They don't really give a hoot about conventional beauty. That's what I understand about New Objectivity so far. I don't really know much beyond that, and there might be a lot more to it.

I found myself fascinated by the philosophy of depicting the context alongside the actual portrait of a person. I've always been very preoccupied with what the context of a situation is. With Bruce Davidson's photographs too, a lot of them are snapshots of a moment that you know is going to pass in a split second. I find myself asking — what's the context of this photograph? What is the literal context of that particular moment in which this was taken? What was the photographer thinking as he or she framed or presented the photograph this way?

I think, very often, the context is the narrative is lost when you present these works. You can't really go around telling people what to think. That's also not the point that a lot of these artists are trying to make. They don't exactly go around with descriptions of the photographs telling you how it was taken, what was going on, and the like. It's up to the viewer to piece it together. Of course there doesn't always need to be a narrative, but I find myself fascinated by these things.

If the artist perhaps leaves out the context of making the work in its display, why do you feel it important for you either as a viewer or a creative to piece together, imagine or conjure?

In terms of what I'm preoccupied with, I think this is a really new development. A preoccupation with either removing things from their context or adding context is definitely something that shows up in my writing as well. When I talk about context, I don't usually want it to be something dramatic. So I'm very amused by banal nonsense. If the context is something completely mundane, that's something that intrigues me. I think that's why I was so drawn to Teatime In The Car. It's so absurd — it's a bunch of people trying to have a picnic in a car by the side of a road! It's a very strange sort of arrangement! But at the same time it seems so normal. If I passed by someone doing this, you'd think to yourself, "Oh, I hope they're having a nice day". Yet when it's in a photograph frozen like this, I find it strange. I can't really explain why. But I can explain my preoccupation with these everyday moments.

I've started to realise that a lot of the conversations that feel the largest, the moments that feel the largest, or the largest emotions that one experiences happen within very dull, normal, everyday situations. There was once I was in a car with a couple of friends, going out, and we were all laughing at a joke that someone had made. The joke would not have been funny in any other context except for this particular one, and we were just passing by these people on the street. It was just one of those situations that would go on to become something that everyone would remember. That would go on to become a big inside joke for all of us. Nobody else outside of the car would have known what was happening. I wouldn't have known what was happening in that moment for the couple standing by the side of the street. They could have been in the midst of breaking up. A whole world of things could be happening, and you wouldn't even know. All this context is lost, because that moment isn't something that you can always have full access to.

Do you find yourself working a lot of this into your writing?

Yeah, I think so, but in different ways. Sometimes I'll remove the context entirely, so I will write images that just pick up on everyday scenes without giving them meaning. Other times, I try to deal with the idea itself — of how one moment can just unfold into something incredibly significant for someone. I don't know why it's such a huge preoccupation for me — it just is.

Photography does that in a very obvious way. Moments come and moments go. Photography works to crystallise these situations before they pass us by. On the other hand, when one thinks of writing, that might not be the immediate impression of why one writes.

Yeah, because you think of the narrative in writing. You don't think of creating a snapshot the way a photograph would. I would say that a photograph even obscures most of what is happening anyway. The viewer doesn't know what's going on beyond the corners of the photograph.

I've really come to think of photography as something that makes the world look as if it's been distilled down to a single frame. It's also why so many social media photographs are so misleading as well. I don't mean this in a grand way where it's deceiving us from the meaning of life. It's more of how sometimes when a photograph is taken against this amazing background — we sometimes don't realise that it could actually just have been taken against a shrub.

It's all about how you frame the picture, and how you frame a photograph sometimes leaves out or obscures quite a bit from view. That interests me because I want to know what's not there. Is there a guy off the side of the photograph peeing in the bushes? We don't know. (laughs)

You've been fascinated by photography for awhile now. What is it about it that you're drawn to?

It's because when I'm in a moment, and I want to take a photograph of it, it never comes out the way I want it to. That's very strange to me, because when you think of how photographers see their frames and know exactly how to make it happen — I realise that I don't even have the instinct to begin to know how to do that.

I think it's also because a lot of what I see is informed by what I'm feeling at the moment. I haven't figured out how to make it correspond to an eventual visual image that I manage to capture. A large part of why I'm so fascinated by how others have photographed surrounds the thought behind a photograph, what the process is like, and what sort of spirit the photographer was trying to capture — as compared to how it then came up in the visual final product.

You use a lot of images in your writing as well, and quite a few of your published poems are centred around a single visual image. How do you see the role of images in the logocentric arena of writing?

My relationship to images in my writing has been around since I wrote Bursting Seams, and those poems are incredibly image heavy. It's also a relationship that has changed a lot.

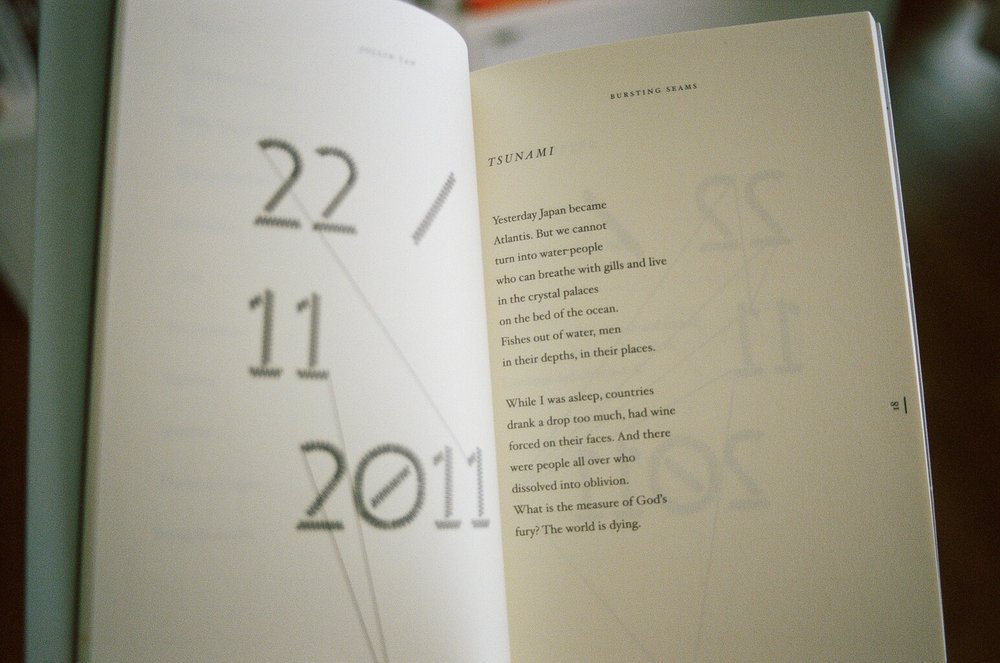

In Bursting Seams, the preoccupation was just to find an image — like, a typical image — and use it in an unusual way. There's a line in the poem, Tsunami, that goes: "While I was asleep, countries / drank a drop too much". It's a dead metaphor, you know, to drink a drop too much or to drink like a fish. Because we use these images so often, we don't always think about them. When I write, one of the ways I'd push myself would be to take these clichés and use them in unexpected circumstances. This played out in a lot of different ways within Bursting Seams, and that was the central style going on with that book. I wanted to take things that I was familiar with, and then reshuffle and change them into something else entirely.

More recently, I took a huge break from writing. I don't think I wrote at all between 2015 to 2016 — or I did, but it was all trash. When I started writing again, it was actually almost instinctual to start writing with images the way I do now. I didn't realise this until quite far in. I had to do a workshop, and whilst preparing for it, I had to think about the different ways I write so that I could put others through the same process.

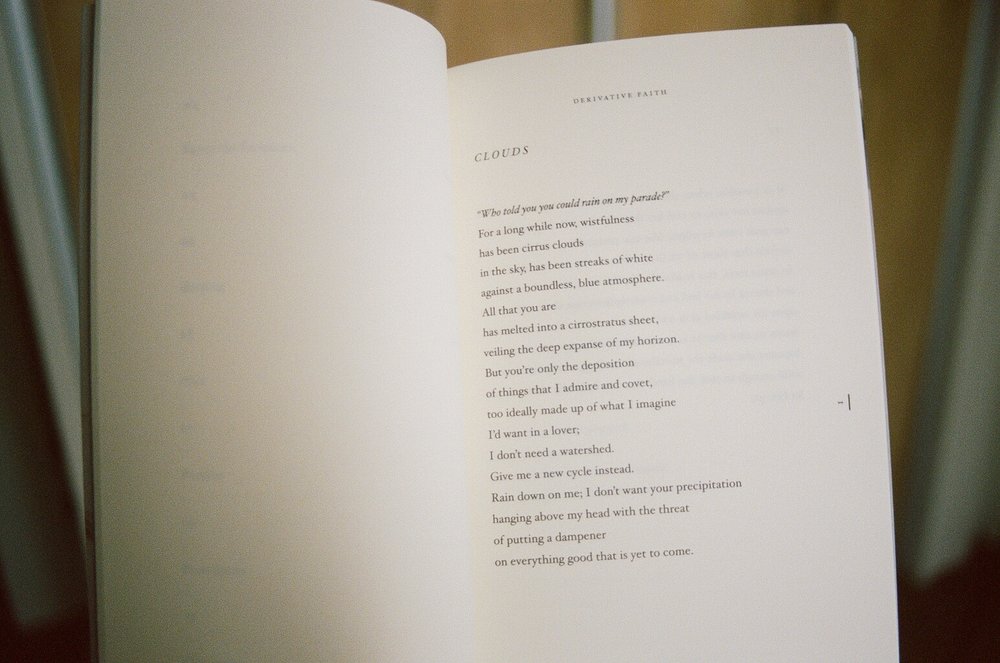

The way I write with images now can be described as using flashes of images. I'm not trying to create a coherent narrative or a coherent poem around a single image that can be looked at via different perspectives.

Instead, I now use a variety of images that come to mind to talk about what I want the poem to get at.

I was studying Romanticism in a module once, and Romantic poets were all about sensation. They weren't Romantic poems because they wrote about romantic love, but they romanticised all the sensations around us. They'd try to document every sensation they felt — every blade of grass and every sun ray. This related quite strongly to what I learnt about later Modernist poetry. A lot of the Modernist poets had come to acknowledge that their works could never recreate the entire experience as it was felt. No poem was ever going to replace the reality of a moment, and the most one could do was to use one's words to approximate the experience instead.

I'd like to say that what I do with images now is a sort of approximation. When things happen to me, and I feel very strong emotions about them, I get very visual flashes — I get visions of what it feels like. I can't really explain it without sounding melodramatic — but it is melodramatic, in a way. My thoughts become incredibly visual, and I don't always think in words whenever I'm in the thick of an intense emotion. So I started trying to write these images of physical sensations down. This is how my most recent works have come about. I've been trying to write images that can encapsulate, or can get close to, a particular feeling in order to describe what the feeling is.

I write in a bid to process things. Part of that processing is being able to put words or images to feelings that I have. Since I experience feelings in ways that are mostly visual, it only makes sense to write about them in ways that are mostly visual as well. Of course these new poems still have a central focus as to what emotion it is that I'm feeling, but I've been depicting them through flashes of images. This is very different to me taking a single image and trying to write a poem out of it, which was what I did in Bursting Seams.

Was that a natural development for you, or did something happen along the way to make you reconsider how you approached the image in your writing? Did it stop being enough as a writing style?

It was an instinctive development. I wasn't consciously thinking of how to change up my writing style, but it started from me trying to put down images that correlated to what I was feeling.

You mentioned earlier that you see your writing as a means of processing, and I think that comes through in a lot of the works you've published so far. For example, you write about deeply personal matters such as body image issues in Bursting Seams. Yet at the same time, the book is a larger critique on how society polices and values the bodies of women. The book tackled both the individual and a larger agenda at the same time. How do you use poetry as a vessel to do both at the same time?

I feel like [a larger critique of society] wasn't what I was trying to do with Bursting Seams. I was always aware that these issues had to be talked about. Because of that, I think the book really reached people and said things that weren't been said very often at the time. But I wasn't trying to deal with larger ideas. I was really just trying to process things for myself. That's also kind of the strange thing about confessional poetry.

I wasn't trying to do much with it. I was nineteen and whining about how I didn't feel pretty. But the fact is that a lot of girls who are nineteen or twenty today still do feel like they're not good enough. In that way, it was a struggle that a lot of people shared and were able to relate to. I wasn't trying to make a statement. In a lot of ways, that still carries. Even in Derivative Faith and the manuscript I'm working on now, I'm not trying to make statements about the larger society. I'm just trying to write about things that pertain to me. With Bursting Seams, it probably just happened to be one of the things that people wanted to talk about at the time. I don't think that's going to be the same with the manuscript I'm working on now.

Your words do tend find people where and when they need it. You've gotten messages over the years from younger girls who have expressed their thanks to you for writing the poems that you have. How does that make you feel?

I feel really heartened by it. A lot of these messages came over the past couple of years. It's been about six years since Bursting Seams was published, so these messages start coming in about four years later. When you've published something for awhile, you kind of look at your younger writing and think that it's juvenilia. I was just whining about feeling ugly, and it was valid, but it's just me whining. But then you get these messages that you never expect to get, from people who say things like, "Thank you for your books, they really helped me through this period". I've always known that words can reach out to people in this way, because that's what happened for me. The works of other poets have touched me deeply. But I suppose I had never really thought of my own poems travelling in that way.

It was a really nice surprise, and it really came at a time where I needed to hear that the things I was doing weren't just floating out to the universe and disappearing. They actually land somewhere. I think any writer will agree that if someone comes up to them and says that they really engaged with his or her work, it's something that touches you and is really heartening to hear.

Going back to when you first started writing, tell us why you came into writing and what sparked it off for you.

I really did start with reading Enid Blyton, but I don't think that was the start of my poetry. That was just me trying to write fiction, and I think every young kid has gone through that storytelling phase. At the time, I wrote that connection with Blyton into my bio because it was one of my earliest connections to writing.

I only started writing poetry in junior college. It was only then that I started studying poetry in a very thorough manner, and my teachers were great with that. It was more of an instinct that a conscious decision, really. When I started writing poetry, they were not written in conventional forms. They weren't even written in free verse, because I had no idea how to go about the line breaks. They were just really short flash fiction pieces, and some of them didn't even have enough of a narrative to be called flash fiction. That was when I started intuiting that these could be poems instead.

I just found it easier to say something in a more condensed manner, especially when it has to do with feelings or things that have happened to me. It isn't easy for me to make a narrative work — fictional or not — because I just can't get the characters right. I don't have character voices in my head. Poetry was the most instinctive, and the easiest for me, to get better at with practice. Writing poetry also felt more me the more that I did it.

It's been six years since you've published your first book. You've gone on to publish your second, and you're now working on your third. What do you know now that you didn't know then — either in terms of your identity as a writer, or your style?

I don't think it's in terms of things that I now know better about, but there's a difference in the way that I write. For some poems, I find that I need to do a lot more research in order to write them. This is opposed to writing poetry about yourself, where you don't need to do research in order to do that.

⁴ A Stitch In Time, David Medalla

National Gallery of Singapore, 1968 — Present

Could you give us an example of a poem where you engaged in extensive research in order to write?

I wrote an ekphrastic poem in response to an artist, David Medalla, whose work hangs in the National Gallery of Singapore. In order to write the poem, I had to do a lot of research on him, and where the particular art piece came from. I didn't want to write a poem that merely dealt with the visual components of the artwork.

I wanted it to speak to the same central ideas that the artwork was about. I had to do research into the ideas that the artist was preoccupied with in order to see if I shared any of these preoccupations, or if I could come at it from a different angle. But other times, my poems just happen.

Not all of your poems are about important works of art, and neither are they all about your feelings as well. You've recently wrote a poem about a scene in Mad Max Fury Road as well.

That came from me watching Mad Max Fury Road at midnight one night. After finishing it, I was like, "Holy shit, this is really good, and Charlize Theron is really hot". From there, I sort of went down a rabbit hole of Tumblr posts dedicated to analysing the movie, its characters, and its themes. Reading those posts, I realised that I had to write a poem about the movie. So, I did, at 4am in the morning.

Obviously, I felt really intensely for that movie because I am a giant nerd. But that's not what I meant when I talked about research. I use art in my poems when there are certain ideas that I want to deal with, and in order to do so, I have to do research. If I'm going to bring in an artwork into my poem, I want it to go beyond how the artwork looks like or how beautiful it is. I want to know where it comes from and the ideas behind it.

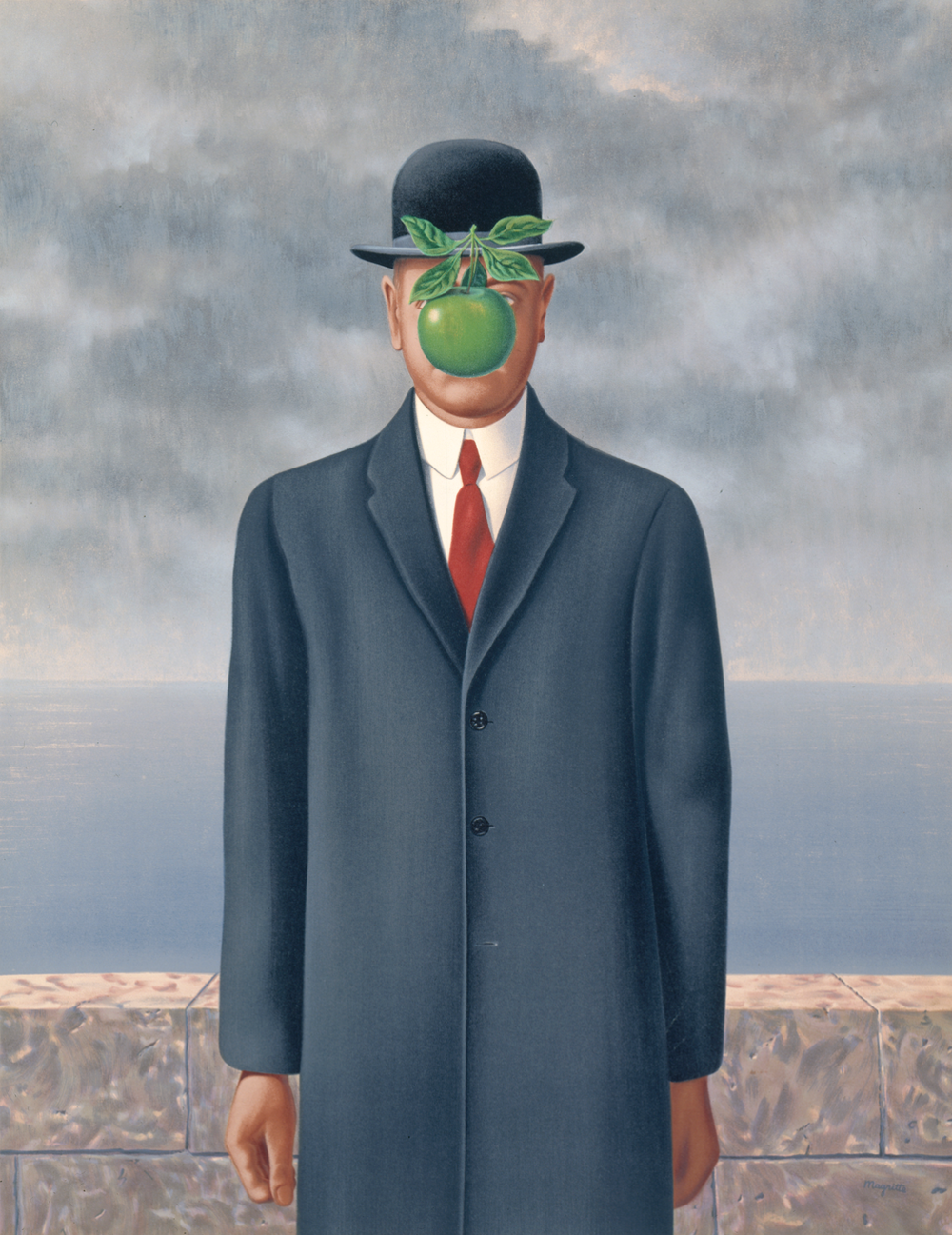

⁵ The Son of Man, René Magritte

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1964

How do you include yourself into such poems without it sounding like an analysis of the artwork?

It doesn't sound like one because I'm not doing an analysis of the artwork. I'm not looking at something and saying that the aesthetic of the work corresponds to how I feel. Instead, I'm interested in the context within which the artwork was built. It comes back to me writing flashes of images. When I write about an artwork, I want to know that some part of it corresponds to what I'm thinking about in the moment of writing.

There's a piece that I recently wrote that featured René Magritte's The Son of Man. I was dealing with something for awhile, and it had come to a point where it started to feel a little absurd. I wanted to refer to a Surrealist or absurdist piece of art in order to ground this feeling, so I did research into the painting so that I actually knew what I was talking about when including the work in my poem.

Some would say that the context of the artwork isn't important, because what should matter is how one feels when one encounters a piece of art. Considering that, why is it important for you to understand the context in which an artwork was made? Why not just spin off on the fact that you felt a particular way when you saw this work of art?

It comes from a weird obsession that I have with needing to know where things come from. Obviously I'm not going to be including the context of every artwork I reference into my poems, but just for myself, I want to know that I'm not writing about something in relation to how I feel. To say that because this is my poem and the artwork should suit my emotion feels a little entitled to me. It's not so much wanting to know the context so that I can deliver the context, but wanting to keep it at the back of my mind so that I'm not vastly misappropriating the artwork and its meaning. I know it's not the concern for many writers out there because art is meant to be open-ended, but I would personally prefer not to be doing that.

I don't want to go to an artwork and ignore its original intentions or contexts. When I start researching about where artworks or poems that I'm referencing come from, it sometimes helps me see that there are a lot of things within these works that resonate with what I'm trying to say in my own poems.

When I write academic essays, it gets even worse. When I wrote an essay for The Deepest Blue's Exhibition Publication on Zelda Fitzgerald and Virginia Woolf, the research I did was really obsessive. I delved into what kind of lives they both lived, the people they surrounded themselves with, and the reasons why they produced the works they did. I don't usually do this for poems, but I can get quite obsessive with research.

Your new website is up, and on it, it seems that you're looking at working on more essays. Are there things that you've found essay writing to lend itself to quite easily as compared to writing poetry, and do you find yourself leaning towards the longer written form now?

Poetry, for me, is about finding words to describe things that I already feel or think. Like I said, I think in very visual ways, and I don't always have the words for it. On the other side of things, essays are how I learn things. In doing so much research, one obviously gains a lot of new information that can help or force you to unpack the way you understand things.

By analysing the way you look at a text, be it fiction or non-fiction, it helps you understand why it has a particular effect on you, and even where that effect might come from. It's something that gives me a lot of new insight, and teaches me a lot about the way I see the world.

The research also functions as a way for me to learn about things that I've always been interested in, but have had no idea where to begin. So I suppose I use the text to approach theories or concepts that I've always wanted to know about.

Writing the essay and formulating the analysis is actually very routine for me. There's a very strict process as to how I go about doing this. I start with bullet points, and then I put them into full sentences. From there, other things develop, and I start rearranging points according to how they might flow or develop best within the structure of an essay. So that's me teaching myself something, and having a tangible outcome for what I've learnt. The essay is the final product of the sort of things that I've tried to absorb, synthesise and put together. In comparison, the poem comes across as — hey, here is a thing that I felt.

Your process for writing poetry is really logical as well. The way in which you edit your poetry is rigorous and thorough, kind of like how you're describing writing an essay here.

I can't write a poem in the same way I write an essay. With an essay, I can sit down, research, plan an argument, plan the points for the argument, develop those points, then write it. But with a poem, I can't plan it in quite the same way. Poems really just come when they do.

Do you, then, see it as you exploring different aspects of yourself?

Yeah, I guess so. They're just different writing processes and styles. The rigorous planning would not lend itself well to writing poetry the way that I write it. I suppose this is also me trying out different ways of writing. With poetry, I've been exploring the image-heavy style, but I've also been experimenting with different sorts of tones. The essay writing, then, is just a way of experimenting with something that wouldn't work with the poetic form.

⁶ Tsunami, Jollin Tan

Bursting Seams, 2012

⁷ Clouds, Jollin Tan

Derivative Faith, 2013

Bursting Seams, 2012

⁷ Clouds, Jollin Tan

Derivative Faith, 2013

How do you see these poems and these essays you write in relation to each other? Do you see them coming together in the future, or do you see them as rather separate aspects of your identity as a writer?

I currently see them as quite separate. Not in the sense that they are completely unrelated, but just that they speak to completely different audiences. Because of that, I don't really see how they could start to relate to each other. I do see them dealing with the same preoccupations, but I don't know how they could come into the same circles.

I feel like, at the moment, they belong in separate books. They take very different tones, and I'm not sure if they could form a cohesive collection. What would this collection even be saying? I also don't see my works coming together in the same way a volume like The Collected Poems of Anne Sexton has.

Is it important to you that every collection says something?

For me, at the moment, yes. It has to, at least, not feel like it's all over the place.

How do you make decisions surrounding what to include or exclude in order to advance a collection's message?

I'm going to leave Bursting Seams and Derivative Faith out of this answer, and only speak to how I feel at the moment. For the manuscript that I'm working on, I started off with trying to put it together tonally. I wanted it to be the kind of book that mostly takes a rather understated tone. I wanted it to be a little quieter in terms of how it says things, and that really works because a lot of my newer works are dramatic, but with a subdued tone.

As for what it's saying, and how — it's still a process I'm in the midst of working through. When I feel that poems aren't contributing to the collection, I've actually been taking out poems and replacing them with others. By not contributing, I mean that sometimes a particular concept has been fleshed out enough through a couple of other poems in the collection, or a poem no longer adds to what I'm trying to say with the collection.

This latest manuscript is about heartbreak, but there were many different stages of the heartbreak for me. There were phases where I was angry without realising it, others where I was livid in my anger, and it also got to a point where I was just done. For every phase that I'm exploring, there can't be too many poems going on and on about it. The collection is obviously not sectioned off in such a linear manner, but I didn't want to have too many poems under a single category because it then takes a very self indulgent turn. Of course, every book that talks about heartbreak is self indulgent, but that wasn't the central message I wanted to pursue.

In terms of deciding which poems stay or which poems go, it comes down to how much of the collection should be dedicated to the various phases I'm trying to flesh out. I'm not trying to make a definitive statement with this manuscript. It's definitely a collection of smaller realisations, so I need to make sure that each of these parts are portioned effectively. I need to ensure that each part is given enough stage time.

When do you know when you're done tinkering with the balance of a collection or a poem?

I don't know. There was a point where I thought I was done with the manuscript I'm working on now, but I wasn't. I really just needed to let it sit for awhile. So there will be times where I feel like I can no longer edit the work. Yet that also comes from being oversaturated, and from knowing every line too well. Because of that, I can't see how a reader would approach my work outside of the context I'm familiar with. So I often have to let my works sit for awhile before coming back to it with less of a focus on why I wrote things that way.

I don't think I know when it's done, but I can sort of tell when it's becoming something else. This applies to both an individual poem and a collection. I can tell when it's becoming something else, and at that point I'll have to sit and reassess if I do want the work to morph into something else. Do I think it is better for it to grow into something else? Maybe that was what I was trying to get at all this while, or do I want to preserve something of the original notion. Depending on which it is, I'll either have to stop or continue.

With poems, it's easier to tell when they're done. I know when I want a poem to say something, and I don't want it to evolve into a different poem altogether. So that's how I know that I have to stop changing words and lines. The process of editing is, firstly, cutting out things that are repetitive. You then work on changing lines, images and words to affect the way the poem sounds. It becomes very clear to me when I start to change things a little too much. It ends up looking quite fuzzy, and it becomes incredibly different from the original poem. When that happens, I then have to check myself and ask if I want to change that line back to what it was before, or if I'd like to go with the editing process.

With a collection, it's slightly more difficult. What you want to say with a collection is something that can keep changing. Since it's a bigger project, there are a lot of poems in there as well, so you're not longer looking at just simply changing a line or two within a single poem. It's harder to tell. If you take out one poem, it might not look too different. But if you put another poem in its place, the entire collection can then take on an entirely different voice. Those are the sorts of shifts that one has to deal with, I suppose, and they're harder to quantify.