Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Re/Discovery

Issue: On Re/Discovery

Juria Toramae is a Singapore-based, Moroccan-Thai artist whose work engages themes of cultural dislocation and the natural environment. Her practice is fieldwork-oriented, driven by a longstanding interest in making visible histories and ecologies that would otherwise go unnoticed. She works in the intersection of video, photography, cartography, painting and installation. Her work has been presented at local and international festivals and venues.

In your recent video works, such as Feathered Islands, Uncanny Lagoon and Pelagic Dreams, you use

AI and its ‘memory’ of

various creatures to generate new life forms. The machine’s interpretation of

possible life forms creates an aesthetic that is both mesmerizing and eerie. What

drives you towards using machine learning as a tool, and what are some of your

considerations when training the algorithm to create this arresting effect?

The generative adversarial network (GAN) is a type of machine learning model that creates realistic replicas in different forms of images. I first came across Mario Klingemann and Anna Ridler’s practices, and they use this technology differently in their works. Klingemann started his explorations before this algorithm was available, wanting to create haunting images of paintings that were perpetually moving. He lets the machine run wild, and does not curate or dictate what the machine wants. Similarly, Anna Ridler explores real time and non-real time, but uses her own photography as dataset. I have accumulated an archive of marine life documentation, and I have always wondered about the representational quality of these images. I feel uneasy about certain documentary styles, especially one that highlights the hierarchy of marine life species. For example, soft corals might be portrayed as being less important than hard corals; nudibranchs are just cute organisms; and the octopus is more interesting simply because it is intelligent. This hierarchy is discriminatory. Who are we to decide for them? When I go through my own archive, I realize that I also categorise things based on a certain mode of organisation. This quality of machine learning models allows me to capture an in-between space—to imagine an evolution between organisms, and to capture the interconnection—perhaps genetically, morphologically, and philosophically. I want to avoid a specific representation that makes one appear more important than the other. It is rather colonial to think that we have so much agency and authority to categorise these life forms. That is why I decided to experiment with and learn this approach. I wanted to capture what I had in mind—the in-betweenness.

My consideration in building the dataset is largely formal. It is a lot of manual work. For images that cannot be replicated, I need to do colour correction or tweak the resolutions to ultimately create the narrative that I had in mind. Pelagic Dreams expresses the idea that the ocean is dreaming. In a dream, things are vivid and shift from one thing to another without needing to be realistic or to make sense. But at the same time, it also has this enveloping, engulfing quality—like you are in the womb, shifting and moving. Using that as guide, I picked images from my archive and removed them from their environments. This is so that the machine does not pick up the background. For example, I removed a jellyfish from the sandbar or the water to allow the machine to focus on the organism itself. It takes a lot of work with the dataset. If the machine does not pick up certain formal qualities—such as the lines, the rounds, the edges, and the texture—then the experiment really fails. But it is super fulfilling when the output images are what I had in mind, or even better, and when I can put them into a sequence to tell a story.

I feel uneasy about certain documentary styles, especially one that highlights the hierarchy of marine life species. For example, soft corals might be portrayed as being less important than hard corals; nudibranchs are just cute organisms; and the octopus is more interesting simply because it is intelligent. This hierarchy is discriminatory. Who are we to decide for them?

¹

Uncanny Lagoon, Juria Toramae, 2021

² Uncanny Lagoon, Juria Toramae, 2021

² Uncanny Lagoon, Juria Toramae, 2021

The machine-generated images offer new perspectives

on the creation and aesthetic principles of art-making. Through your work, one

experiences an endless imagination of life forms via the invisible mind of a

machine. In what aspects, if any, do these works comment on

human perception and aesthetics in relation to technology?

In my work, the mind of the machine is trying to make sense of all these images that I have given to it. It is the creation of interpolation, as well as confusion. The machine questions what makes these images similar, and looks for patterns to pick up. The invisible mind—the algorithm—was written by a human being, thus definitely reflecting human thinking and biases. Machines, in general, are a reflection of human perception. They mimic the way we look for patterns to make meaning. We see something and we think—yes, this reminds me of something else. From there, we create a story. I think of this as a a reflection of that process.

Given your

background in photography, image-making and image manipulation seems to be an

area that you often come back to. It is a space where one has the power to document,

curate, or create memories and life. How have those experiences informed your

exploration of this new medium, and what are some of new areas you have

ventured into?

I always go back to mixing things up and doing composites, but I realise that there are more possibilities when combining mediums or approaches. This GAN approach is really interesting. Before this, I was limited to a static image. When I wanted to create a sense of in-betweenness—be it through composites, installation, or overlaying things—there was always something missing. I could not capture movement, or a sculptural quality, or explore the texture of a living and breathing organism. With GAN, I could explore the texture that enlivens the image. In doing so, a 2D image sometimes feels like a 3D one—it is in between sculpture and image. I really like that possibility, and I can imagine creating a longer video or a short film with this technology. There is so much to do with it, especially when you begin to curate or control what the machine does. I would never let it run on its own, because it is actually very limited in its capability. It is restricted to the algorithm itself.

Documenting and creating memories was my way of finding a sense of belonging and resonance. As a new resident in Singapore, I need to know more about its history and its people, who are now my neighbors and friends. I have always been very curious. My family moved frequently because my father was a journalist. I have not lived in a place for more than four years. Although we kept moving between the same few countries, things were always changing rapidly. When we returned to a place after being away for a while, I constantly had to play catch up. In a way, it was ethnographic. As a kid, I always liked to run away from home to explore the market or the sea. My first memory is of the sea. I was born five hundred meters away from the beach, in Morocco, where it is very cold. It was a rocky beach where few people go, but the memory of it is still very vivid in my mind. My paternal grandparents were from the tropical rubber plantations, and my maternal side lived in the snowy mountains. Each country we lived in had a very different topography, and I always feel the need to go and see what is out there. That made me very active in documenting. I wanted to understand what was going on, what happened before, and what is possible. I have an overactive imagination and curiosity—that is also why I do what I do.

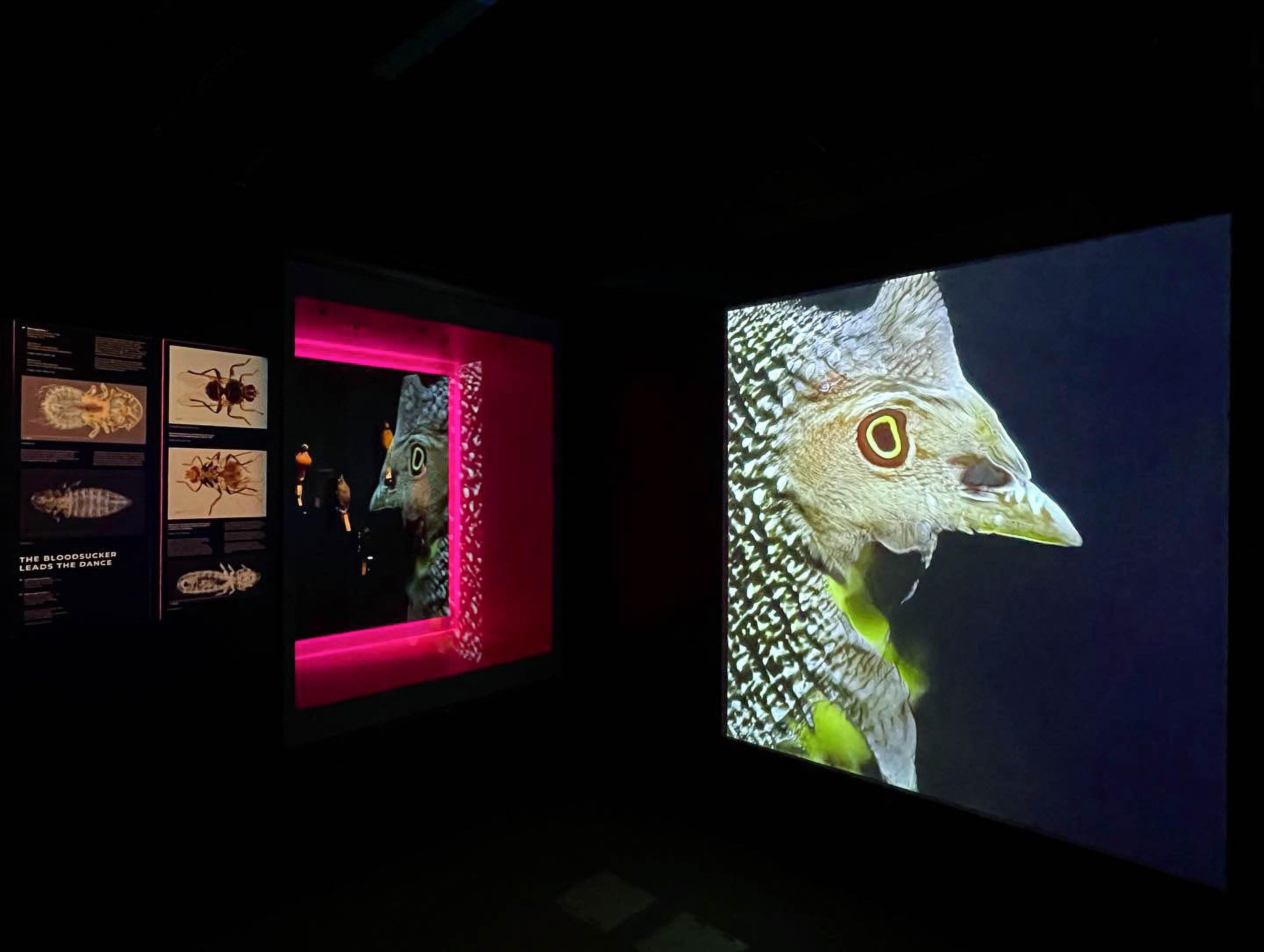

³ Uncanny Lagoon, Juria Toramae, 2021, Installation View at Yeo Workshop

⁴ Feathered Islands, Juria Toramae, 2021, Installation View at Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum

⁴ Feathered Islands, Juria Toramae, 2021, Installation View at Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum

The network of knowledge you express in your

works seem to be developed from an extensive amount of research. Knowing your

interest in outlying islands around Singapore and the memories hidden in those

shorelines, how did you start exploring these uncharted territories? How do you

transform what you have rediscovered into your own creative expression?

In the case of Singapore, I started with its history and meeting people in heritage groups, and one thing led to another. I am always drawn to the environment— both humans and nature, as a part of ecology. I am especially interested in changes and displacement because it is what I have been going through. From that point of entry, I read nonfiction, historical materials, and archives. That is how I developed a lot of my works. I looked at what the islands and shores were like before. Old maps contain a lot of knowledge about what is depicted and what is removed. Some islands disappear, and other islands used to be a single island. The names of the lands can be strange too. There are a lot of stories that reflect the decisions of both the mapmaker and the government of the time. My research has little structure. It starts in a place, and branches out from one thing to another quite organically.

The outlying islands are fascinating. Most of the settlements that were there before have mostly been forgotten or are not spoken about, even though the latest resettlement of residents from these islands was rather recent—it happened at the beginning of the 90s. Yet there are certain people who remember it very vividly, with interesting anecdotes and oral history. There are many small islands around the main island of Singapore. From what I’ve read in the newspapers, the National Museum of Singapore organised free tours to these islands back in the 60s and 70s. At the time, they were oversubscribed. They did not realise that people would be so interested. There were trips to those islands in the 60s where people went fishing and did all kinds of things. Some people lived on those islands too because they found living in Singapore too expensive. Now the islands are pretty much barren, and are occupied mostly by industries or the military. In a way, they are a time capsule. I feel intrigued and resonate with these stories—which are about movement, the inability to access certain things, and the sense of home.

Old maps contain a lot of knowledge about what is depicted and what is removed. Some islands disappear, and other islands used to be a single island. The names of the lands can be strange too.

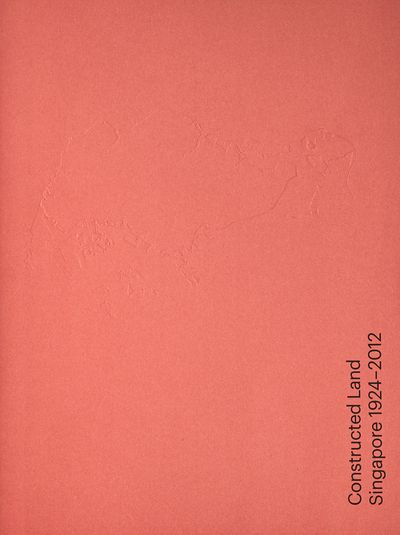

⁵ Constructed Land: Singapore 1924-2012, Milica Topalović

⁵ Constructed Land: Singapore 1924-2012, Milica Topalović2014

You have expressed a strong sense of intimacy

with the ocean, islands, and memories that are rooted in certain environments.

How have you been thinking about one’s connection to a place, especially in

relation to land transformation and the soil history of Singapore?

When I started learning more about land reclamation in Singapore, I realised that people were moved and displaced abruptly. They were suddenly told to move within a certain time. How can the government do that? Even though people may be compensated with, for example, a HDB flat in West Coast that is near to their islands, they should not be moved just like that. The book, Constructed Land: Singapore 1924-2012 by Milica Topalović, talks about Singapore's approach to transforming its landscape. It is interesting that Topalović describes the process as Singapore’s scorched earth method, which means an erasure of everything. The land becomes blank, terra incognita, and it starts all over again. That was mind-blowing to me. These actions are contradictory to how the government talks about promoting culture and heritage. It may be okay to build new memories, but to what extent? Even in the city, things get torn down very easily. There has been more resistance recently, and it is fantastic that Golden Mile Complex will be preserved. However, the Pearl Bank Apartments were demolished. There is a pattern to the way that iconic landscapes of Singapore are disappearing. Singapore is continuously reinventing itself, but at what cost? How does one make Singapore home? Is home a place, or is it one’s feeling about the place—one’s memory palace? I think that it is about a sense of belonging.

⁶ Pelagic Dreams, Juria Toramae, 2021

⁷ Pelagic Dreams, Juria Toramae, 2021

⁷ Pelagic Dreams, Juria Toramae, 2021

⁸ Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas, Stefan Helmreich

⁸ Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas, Stefan Helmreich 2009

Your works also call attention to one’s

relationships with objects. The book, Alien

Ocean by Stefan Helmreich, adopts a culturological

account of the ocean. Perhaps the book raises the question of how we can

examine life forms in a framework that centres the nonhuman, similar to the

ideology of Object-Oriented Ontology. How has the book informed your

relationship with marine creatures or nonhuman life forms in general?

Stephan’s book is one of my favourites, besides Rachel Carson's The Sea Around Us. I am always drawn to ethnography, but what I really love about Alien Ocean is that it problematizes the way we’ve othered the ocean because we do not know it enough. It is hard to get to know it because it is not a place that we live in. The book also talks about the alien-like quality of the ocean, and how we have been categorising species. What are life forms? Are microbes life forms because they are invisible? The book also explains the tree of life, where there are genetic links between all species. Inherently, a species could belong to any taxon. The idea of the tree and classification becomes fuzzy, and that has stayed with me. It makes me think about the way we look at marine life, or at any animal or plant. How we think one is different from the other one has more to do with its environmental value. A recent project that the National University of Singapore undertook in partnership with other universities studies the environmental services of mangroves. They argue that we should preserve all the mangroves we have now and look at planting even more of them because they are of great environmental value. The cause is great, but the way they term and define things as if they were only of value for human beings is also mind-blowing.

It is fascinating that you mentioned Object-Oriented Ontology. It has always bothered me when people think about whether there is life in space, or aliens on Mars. I want to ask them—have you seen the ocean? Have you looked underneath the soil? Have you dug into the volcanoes? There are amazing and weird forms of bacteria that can withstand the most intense of environments. I often find alien movies boring because they follow the same template of something scary, something dinosaur-like, or something green. Yet, there are so many other forms—even here on Earth. That brings me back to the beginning of our conversation. When I conceptualise the familiar yet eerie quality of marine creatures, I have decided they cannot be scary. We are so disconnected from nature—to the point that we do not see ourselves as being a part of it. There are so many horror and science fiction stories that frame the nonhuman as threatening, alien, and scary. This feeds into the bias that these life forms must be kept away. I do not want my work to cause that effect because that is not how I feel. It would be counterproductive. When one’s scared, they do not want to get to know or care about the object. Instead, all they would want to do is to kill it or run away from it. There is always the possibility of this extreme, and I do not want my work to go there.

It has always bothered me when people think about whether there is life in space, or aliens on Mars. I want to ask them—have you seen the ocean? Have you looked underneath the soil? Have you dug into the volcanoes?

⁹ Let’s Walk, Amanda Heng

⁹ Let’s Walk, Amanda Heng1999/2018, Performance presented at the M1 Singapore Fringe Festival

You participated in Let's Walk by Amanda Heng in 2018. In the live performance, the act of walking takes on a meditative

quality—it becomes a way of examining one’s body and inner strength. Do you draw

inspiration from these possibilities in art-making, where you are directly in

conversation with the community, or the way that we can rediscover simple

actions to generate new meanings?

I was a resident at The Substation at the time, and joined Amanda Heng’s re-enaction of the performance. It was quite transformative. At the time, I was constantly thinking about my approach and my process of art making. Now, walking takes up ninety percent of my documentation processes. I don't dive for my documentation; I go for intertidal areas when the tide is very low. I usually have two hours to walk on the sandbar. It's the opposite to Let’s Walk. I have to walk carefully and very fast. All my senses must be engaged. I have to be alert to the turning tides or changing weather. There is always that sense of urgency and danger—but with pockets of calmness. In Let's Walk, everybody walked backward with a mirror and had to trust the person behind them. We had limited vision and had to walk slowly. Corporeally, it felt like the opposite of the way I do my documentation. That experience inspired me to walk backward, literally, through my archive. What if I were to think about things the opposite way—to unlearn, or take things from the end to the beginning? How would they flow? My reading of this experience is different from the intended interpretation of Amanda’s work. With Let’s Walk, Amanda was commenting on the body, gender, and the experience of being a woman. However, as an artist and a participant, the process of doing something together is also about taking time, trusting the people next to me, and reevaluating my gaze, my perspectives, and my creative process. It was an unexpected outcome from joining that walk, and I am very grateful for it.