Kamini Ramachandran is an oral storyteller with a strong Asian and Nusantara repertoire influenced by her childhood in Malaysia and her connection with the jungle. Known for her intimate, site-specific and experiential storytelling sessions, she is currently working on collaborations that include sound, foley, installations and visual art to support the spoken word. She is producer of StoryFest Singapore, and nurtures Young Storytellers at The Storytelling Centre Ltd.

Sit in on one of Kamini’s storytelling sessions, and it might feel as if you’ve been transported to another place altogether. Her voice, along with her use of rich visual cues and compelling installations, envelop the listener completely. Following a successful run of O/AURAL WAVES: Spirited Words at Textures earlier this year, Kamini is working with artist Ferry on a new iteration of the O/AURAL WAVES series for 2021.

Sit in on one of Kamini’s storytelling sessions, and it might feel as if you’ve been transported to another place altogether. Her voice, along with her use of rich visual cues and compelling installations, envelop the listener completely. Following a successful run of O/AURAL WAVES: Spirited Words at Textures earlier this year, Kamini is working with artist Ferry on a new iteration of the O/AURAL WAVES series for 2021.

Credit: Jasbir John Singh

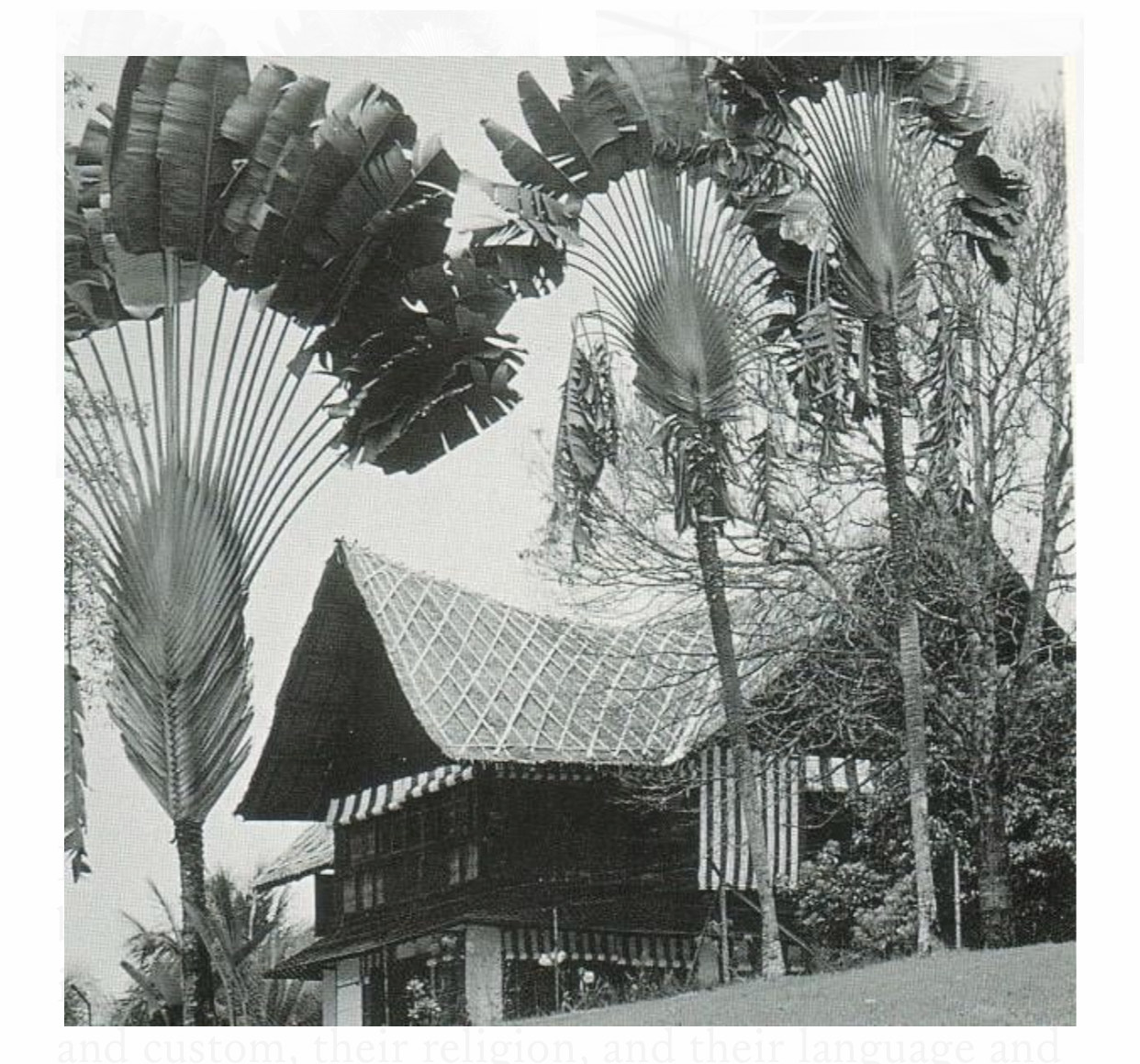

¹ Minyak Bungalow

1906, Rantau Panjang, Selangor

By way of introduction, it’d be great if we could begin by speaking to your childhood and the time you spent growing up in Malaysia. As a planter’s daughter, you grew up in a bungalow on the plantations, and these were formative experiences that have shaped the way you approach your practice today. How would you describe the way these memories have seeped into your work today, either in terms of the landscapes you were surrounded by or the histories embedded into these spaces?

To give you a glimpse into those early years: my father would be transferred from one plantation to another every one to three years. That was the nature of a planter’s life — you never remained in one location for more than three years. I think I must have gone to four different primary schools between my primary one to primary six years. Living in these isolated environments meant that the nearest school was an hour’s drive away from us. This definitely helped with developing my habit of reading, because there really was nothing else to do, and I had to use my imagination. My parents never stinged on buying books. They also were great readers, so they had their own library and bought books for themselves to read as well. Most importantly, they never censored. Everything would be lying around, and we could pick up anything we wanted to read. In those days, and we’re talking about the seventies, people subscribed to magazines. We had stacks and stacks of publications such as Time Magazine, The Economist, and Paris Match. That quiet, peaceful, isolated life that I took for granted, because that was the only life I knew, played a huge role in developing my capacity to read, to be patient for things to happen and develop. We would travel by car on these long journeys and to amuse ourselves, we’d listen to stories that our parents told, we’d sing, and play games together. This was how time passed.

I also went to very rural — you won't even call it kampong (village) because it was beyond kampong — schools. There were schoolchildren from the Orang Asli indigenous peoples, the local village children, and there were children who came from the tin mining, rubber and palm oil plantations. It was a good mix of children from all races and all kinds of backgrounds. The common thread among all of us was that we were not city children. We were not even town children. There was no difference with race, religion, or anything. We played, we talked, and we shared food with one another. These exchanges were quick and immersive ways to build tolerance and respect. This is how we behaved everyday and how we conducted ourselves in school.

I'm fluent in Malay — I can read and write it. Growing up with and listening to the Malay language, both spoken and taught in schools, means that my ear is attuned to the different dialects. I stayed in Perak, in Pahang, in Selangor, and in Johor, and in different places within these big states. There are different local dialects and variations in intonation. The same goes for the way stories are told. For example, my Malay cikgu (teacher) in Johor would tell me a version of Badang or Puteri Gunung Ledang. Later, I’d hear the same story told by someone in Pahang with slight twists, changes, or just adaptations that a storyteller has a cultural right to do. Now that I look back at my childhood, I realise that it was absolutely unusual in its cultural immersion and almost fairytale-like. It really didn’t make me question things like this idea of difference or otherness.

The landscape was also important. Having seen pythons, having seen elephants, having seen tiger paw prints, different types of monkeys, different types of flying foxes, and bats and squirrels, wild dogs, scorpions, and wild monkeys attacking our pet dog — all the drama and disaster that you can imagine happening whilst living in an environment like that. My father was a planter, and my mother loves gardening. They would talk to us about plants, about nature, and about trees. When the sun is setting, and the weather is not so hot, we'd go for these long walks. We could just be with nature, walk and even meander into someone’s mangosteen or durian orchard. Nature, animals, plants, who my parents were, their own obsession and respect for plants, for gardening, for getting their hands dirty, for cultivating their own orchids, teaching me to play in the dirt, to roam around, to walk, and not to be afraid — all of these things definitely piqued my curiosity in the mythology and legends of where I stayed.

Stories were important because my teachers, specifically the Malay teachers, would teach the language through storytelling. Even though we had textbooks and a syllabus, the cikgus were often telling us legends and epics, and that's how we picked up the language. When I moved to Kuala Lumpur for secondary school, I picked up Bahasa Klasik (classical Malay language) as a subject. This is the language of royalty, and it is full of beautifully poetic phrases that are full of respect. Encountering these stories again in my teenage years, now told to me by different cikgus, reinforced this Nusantara world that I felt I belonged in. I am part of the South Indian diaspora and a third-generation immigrant. I can trace my ancestry back to my great grandmother, who came to Malacca from Kerala. But I feel a stronger sense of belonging within this part of the world than I do with India. I think that comes from this very immersed childhood, which grounded and rooted me here. I spent almost ten years in the United Kingdom, and I've been in Singapore now for more than twenty years. These newer experiences in my adult life have shown me that this was, in fact, a very privileged childhood. It moulded me and shaped me to think with this world of words — predominantly the words of the islands, the archipelago, and the land around us — and not necessarily the words of the Western world or anywhere else. Though I am not from that race, I can still tell these stories with great honour and respect.

² Antique Batik Cloth Narrating the Story of the Ramayana

Collection of Kamini Ramachandran

The notion of movement and travel came up quite a bit in your response, and this is something that an antique Javanese batik fabric from your collection touches on as well. You purchased this textile in Yogyakarta and it depicts the Sanskrit story of the Ramayana, a story your late grandfather told you. What would you say the place of migration, travelling and connections is within your practice?

Oral tradition, in and of itself, is something that moves. When we imagine the world as a single landmass before it separated, the people were all together in one place, telling the same stories. When the landmass split, spread apart, and floated away from one another, some of these people also moved. They took the stories that they knew, and they reshaped it, telling it in a manner that adapted to the flora, fauna, the geographical terrain and the temperature of these new places. The kitsune in Japan, the shapeshifting and mischievous fox, is huli in China, is the jackal in India, is the coyote in the Native American tradition, and is the wily fox in the European tradition. How is it that this one animal emerges in myths and folklores across varying cultural traditions, and with similarities in its characteristics and nature? The fox is still cunning, wily, a trickster, shapeshifting, the judge, the one that got away, and the sly one. It is not the romantic and it is not the hero. That stories have migrated, moved, adapted to their new location, and that there are new tellers — these are ideas that have always intrigued me. Each story is influenced by who is telling it, where they are, and what is around them.

I myself come from a line of people who left and crossed the ocean to arrive at someplace else, and I have different languages within me. I may not be a hundred percent fluent in all of them, but it's there with me. I am now working with these stories that have also traveled all over the place, and I'm telling them predominantly in a place called Singapore. As a result of publishing and the ability we have to retell them verbally, words — whether written or spoken — are always floating, flying, swimming, running, and moving. We cannot control it by pinning it down and saying that it needs to stay here. It’s more about the qualities within the story, for example, the heroes, heroines and villains. How can we look out for these qualities rather than trying to look for specificities that isolate the story? These are questions I asked myself. Will my own sons want to tell any of these stories? If they do, how will they tell it? Or will they not be drawn to any of this, and want instead to tell stories from somewhere else? What are the boundaries and restrictions in place?

We don't have tradition bearers, and we don't live in tribes anymore. Tribal reciprocity, and the respect for the seeking of permission, is something that I talk about a lot when I teach. I always acknowledge who I've heard the story from, where I got this version of the story from, whether I have permission to tell this story, whether the people listening to the story then have permission to retell the story, or if the permission stops with me only. I abide by this very, very strictly. I'm not sure if other storytellers are careful about this. An uninitiated audience won’t know about the tradition bearing kind of protocols behind this art form. It is important that due honor and respect is given so people know you didn't invent this or pluck it out of thin air. This way if somebody wants to find out more, you allow them to understand and they can find out more. What worries me is the lack of this practice in storytelling, where people don't do this.

I always acknowledge who I've heard the story from, where I got this version of the story from, whether I have permission to tell this story, whether the people listening to the story then have permission to retell the story, or if the permission stops with me only.

³ A Storyteller Reads — Latha's 'There Was A Bridge In Tekka', Kamini Ramachandran

2017

⁴ A Storyteller Reads — Home, Kamini Ramachandran

2017

2017

⁴ A Storyteller Reads — Home, Kamini Ramachandran

2017

This fixation with understanding things through categorising, compartmentalising or essentializing them has often been described as a Eurocentric or Western European impulse. These impulses almost seem to sit in direct contrast to what you touched on earlier with regard to knowing, bestowing and understanding through gifts. Throughout your practice, how have you dealt with these varying traditions or impulses? Are there certain things that you’ve had to unlearn or detangle throughout the course of encountering or relating stories within a particularly Asian context?

Some stories are sacred. They belong to a specific group of people, and this includes personal narratives. With these stories, there is definitely no permission to retell unless it is explicitly given. There are also specific contexts for such stories, such as therapeutic situations where they are used for healing or for catharsis. It is no longer entertainment and no longer about the art of storytelling. In these circumstances, the story is a tool for application or facilitation. This could be with students, or with a women's group, or with underprivileged boys who are grappling with anger. Personally, I have my own ethics when it comes to such stories. They are not meant to be put on social media. I don't like it when people use that and leverage upon it to then come up with fictionalised versions. It is different from writing an academic essay, for example, because you would have redacted names and sensitive information. In those contexts, you’re not embellishing things. The focus is on the methodology and the topic at hand as compared to the people.

I've always said that if a story wants to be told, it will somehow make itself known. If I'm given themes and asked what sort of stories I can tell around that theme, my usual answer will be to explain that I have a couple of stories that I’ve been telling over the years. However if I’m not going to be repeating those stories, I’ll just need some time before coming back with ideas. It can be as crazy as me getting home, walking up to my bookshelf and something makes me pull up a particular volume. When I flip the pages and my finger falls on something, that’s when I realise that now’s maybe the time to tell this particular story. Am I the one consciously making that choice, or did that story want to be told? Why is it that certain stories want to be told again, and again, and again? I don't get bored of telling it, and the audience doesn't get bored of listening to it either. It’s about going with the flow, allowing things to speak to me, and being intuitive in how I respond.

I've always said that if a story wants to be told, it will somehow make itself known.

There is this deep sense of spirituality or intuition embedded into folklore and mythologies, and this extends to how these stories are told as well. You touched on the concept of intuition within your response — could you elaborate on the importance of spirituality or intuition in defining how you approach your practice?

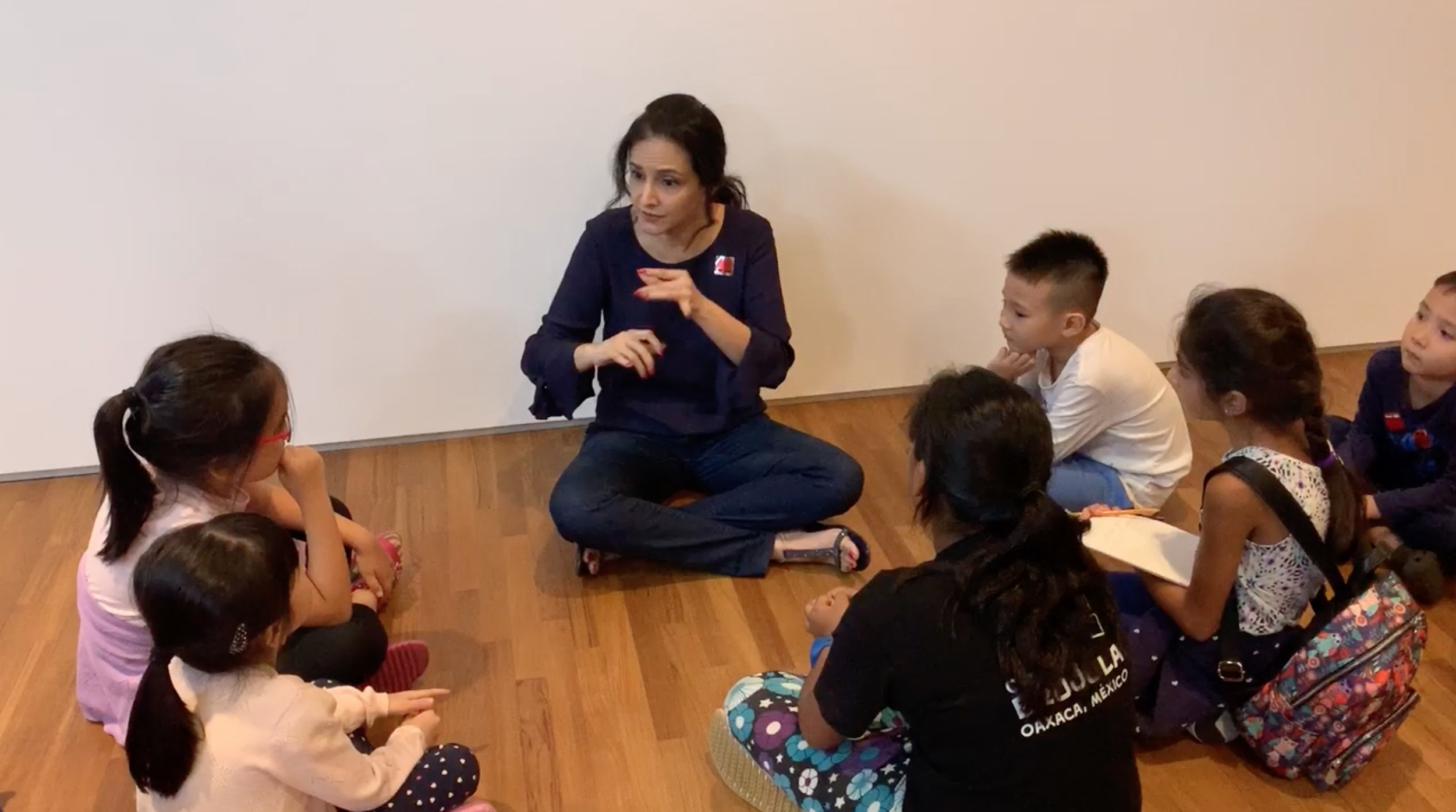

One of the answers to this question is that there is this urgency in me — this fear that this is a dying art form. And whether it's recorded and captured on video, or archived in books, who is actually sitting and telling these stories? I’m not talking about storytelling in the scripted sense of memorising something and dramatising it. I’m referring to the process of knowing a story’s origins, where it came from, how it evolved, the multiple versions of the same story, and how it can be connected to literature, poetry, architecture, food, rituals, taboos, and festivals. There is this fear that I'm only mortal. I'm in my fifties, and I do not see signs of my two sons wanting to practice it the way I do, though the knowledge is deeply embedded in them. You cannot force these things. That's why I feel that I need to educate the clients, the institutions and the people I deal with. My practice comes with its own ways of doing and ways of making. To me, it's not about entertainment. It is the urgency of practicing oral tradition. If you're looking for someone to entertain children, we have to come to an agreement. I’ll respect some of your requirements, but I need to do what I want to do, the way I want to do it. It is not going to be a show and tell or a song and dance session with no soul.

Stories can come to us in texts, and many of us might encounter a story by picking up a book and reading it. Storytelling, on the other hand, shifts this from an individual encounter to a shared, communal experience. Personally, what do you find most compelling about speaking, reciting, or narrating stories? What is the capacity of the human voice in invigorating a text?

I love reading, and I love that solitary activity of being immersed in a book. I love the smell of paper, the sound, the very tactile reading process and I collect a lot of books myself. When my children were young, I read aloud to them and I absolutely loved it. But it was never exclusive. There would be the storytelling without a book or a text, and there'd also be the reading aloud. It was also about getting the children to read as well, so that it's not just me reading to them, but that they too could have agency or power in this activity.

I guess my brain works differently. When I see the word text, it means something that has been written, printed, published or inscribed somewhere. It becomes text because someone wrote down that set of words. But stories, to me, don't necessarily need text. There are stories that I tell that have not been printed nor inscribed. So what is the equivalent of text for an oral storyteller? It is the memory of the person who spoke these words to you. The biggest influence on me, the person who sat with me for the longest period of time and told me the most number of stories, is my late maternal grandfather. He didn't read off a book. Everything came from his heart, his mind, and his memory. It came from elderly folks in the village who told him these stories.

How is that experience of reading a book different to narrating or reading aloud? We are not obligated to a scripted, fixed pattern of words — which is text. We are retelling an emotion, a feeling, an adventure. This is all based on the energy of a set of characters, the energy of the land, the feelings of these animals, people, whoever they are, whatever they are — and we're trying to transfer that energy to the listener. So if I was to tell the story Puteri Gunung Ledang to a bunch of six year old girls, I don't have to follow a scripted text. I know what happens in Puteri Gunung Ledang, and I know how to tell the story in about six to seven minutes because these children are young and they cannot stay seated for long. I could tell the same story to students who have a background in history and literature at a university lecture. How do you do that with a written text? When I see "text", I think of books that have been imprinted, inscribed, published or printed. Words in storytelling, on the other hand, are based in memory. You have had to hear it from someone at some point in time.

For a lot of the people I work with now, their first encounter with such stories are within anthologies, picture books, cartoons or television programmes. I've had people tell me that their introduction to oral tradition was by way of watching Marvel movies. When they realised that these characters were based on Norse mythology — Loki and Thor — they began to see the connections between the different traditions of myths and folklore around the world. You could encounter these stories through text, but would you have a chance of listening to someone tell you the stories of Odin, of Freyja, of Thor and of Loki?

I find the process of telling a story to a living, breathing, listening audience very different to writing and reading in solitude. A writer doesn't write communally — most writers write alone. When the book is published, most of us read alone as well. But storytelling is never done alone. It is very much about you and me. I don't exist without the listener and the listener cannot exist in the storytelling world without a storyteller. We both need each other to be present.

We are retelling an emotion, a feeling, an adventure. This is all based on the energy of a set of characters, the energy of the land, the feelings of these animals, people, whoever they are, whatever they are — and we're trying to transfer that energy to the listener.

⁵ Story of the founding of Singapura from the lineage of Raja Suran to his descendant, Sang Nila Utama (O/AURAL WAVES), Kamini Ramachandran and Ferry

2019, Performance at the Esplanade Exchange @ The Concourse

⁶ Story of the founding of Singapura from the lineage of Raja Suran to his descendant, Sang Nila Utama (O/AURAL WAVES), Kamini Ramachandran and Ferry

2019, Performance at the Esplanade Exchange @ The Concourse

2019, Performance at the Esplanade Exchange @ The Concourse

⁶ Story of the founding of Singapura from the lineage of Raja Suran to his descendant, Sang Nila Utama (O/AURAL WAVES), Kamini Ramachandran and Ferry

2019, Performance at the Esplanade Exchange @ The Concourse

We’re losing touch with ideas of communal storytelling, sitting together and sharing space with one another. It brings to mind how oral traditions are, like certain languages, also slipping away from us. Throughout the course of your practise, what are some of the observations that have stayed with you when thinking about this loss, and are there specificities that you’ve noticed in relation to the Singapore context vis-à-vis other Southeast Asian cities?

In Singapore, this loss of dialects has been heavily discussed. This loss is very evident. When the mainstream is to speak the English language, this can mean that many are out of touch with cultural practices because these practices are done in a language that is no longer understood.

When I came to Singapore as a young mother, my youngest was only six-months-old. I was surprised by the fact that many people here were not aware of Chinese, Indian or Malay postpartum confinement practices. They might have heard about it, but it was more about getting a nanny to take care of the baby so that they could get some sleep. To me, that was really not the point. The point was standing over frankincense, the smoke going up into your uterus, helping you heal, pounding all these herbs, boiling these concoctions, and drinking the essence so that your blood doesn’t coagulate. There are amalgamations of Malay, Chinese and Indian practices of pouring turmeric onto the new mother, in order to cleanse her and protect her from evil spirits. At the same time, it's antibacterial as well. There is also the Chinese practice of tapping brandy onto wet skin in order to ensure that one’s pores were covered. It was such a shock to me that all of this wasn’t common knowledge. That was the early 2000s, and things have evolved now as a result of social media and cultural awareness. Younger people have taken things into their hands, reviving practices like this because they want to know more about them. These traditions are things that an older person would talk you through whilst they are performing them. Whilst they oiled your hair, they would be telling you a story about the tulsi (holy basil) plant. Most of us don’t have that experience anymore. What you can do is to buy a bottle of the oil from Little India and to pour it over your head, by yourself. Grandma doesn't massage it in. This ties back again to my world of storytelling and how it's rooted in heritage and culture. Everything about storytelling is intangible. It only becomes tangible when you practice it — which is to say it, to tell it to someone else, to show it and to do something with it. It is an art form that is activated by the community.

Stories such as Badang, Singapura Dilanggar Todak (The Attack of the Swordfish), Radin Mas Ayu, and Sang Nila Utama are about the only handful of tales that we can anchor in what was then known as Temasek and Singapura. But these stories are part of the larger Sejarah Melayu, which speaks to Malaysia, parts of Borneo, most of what we know today as Indonesia, and parts of Thailand. I find isolating these stories as Singaporean folktales a little problematic because Singapore, as a nation, is only 55 years old. This Nusantara region is ancient, and these stories are known by seafarers too. By isolating them, we are cutting off our connection to the rest of the region. When I listen to the story of Mahsuri, which originated in Langkawi, part of the Kedah state in northern Malaysia, it is undeniable that there is considerable Siamese influence within the story. This is due to the fact that Mahsuri's family hailed from what we would consider today as part of southern Thailand. Yet this isn't a Thai story, or a story from Kedah. The story just happened in Langkawi — Mahsuri lived here, died here, and this is the curse. We need to learn to let go, to ease into these regional boundaries, and to allow seepages in and out, because this can only serve to enrich our understanding.

My husband and I travelled to Myanmar in February this year, and we wanted it to be a cultural trip. When I asked our guide about stories and folklore, he was shocked that somebody wanted to know about all of this. One of the things he said before we left was that the younger generations no longer have time for these stories. With fast-paced progression, this is something that countries such as Myanmar have to grapple with. Going to a place such as Yogyakarta, the vibe is completely different. Wherever you went, most people had the time, were interested in, and knew about such legends. The storytelling tradition is also alive and well in places such as Georgetown. It is a place where people have time, or make the time to read. I was there for the literary festival, and the room for my storytelling sessions was packed to the brim. People were happy to just sit and listen, and it was amazing to be amongst an audience like this. The pace of life in Penang is known to be slightly slower than the rest of Peninsular Malaysia. If you want to spend time being immersed in slow living, then I think there easily is space in your heart for these cultural practices and oral heritage. In that way, these traditions can continue. If you're catapulting towards some form of economic development, there is no time for slow living.

Everything about storytelling is intangible. It only becomes tangible when you practice it — which is to say it, to tell it to someone else, to show it and to do something with it.

⁷ Story of ‘The Gravedigger’ as part of an installation featuring a variety of SingLit authors and texts (O/AURAL WAVES: Spirited Words), Kamini Ramachandran and Ferry2020, Performance at The Arts House

⁸ Story of ‘The Gravedigger’ as part of an installation featuring a variety of SingLit authors and texts (O/AURAL WAVES: Spirited Words) Kamini Ramachandran and Ferry2020, Performance at The Arts House

⁸ Story of ‘The Gravedigger’ as part of an installation featuring a variety of SingLit authors and texts (O/AURAL WAVES: Spirited Words) Kamini Ramachandran and Ferry2020, Performance at The Arts House

Turning the conversation to the way in which you put together your work, let’s spend some time talking about O/AURAL WAVES. O/AURAL WAVES is a collaborative effort between yourself and the artist Ferry (Jean Low). It is an immersive storytelling experience that combines text, soundscaping and foleys. Tell us about how you both approached the process of bringing these different elements together.

I met Jean during the Singapore International Festival of Arts (SIFA) in 2018. We were both commissioned by SIFA, but our shows were often scheduled at the same time, so we never got to watch each other perform. We formed a bond over social media, and got talking. Going beyond the musical, I told her about how I’ve always been intrigued by technology, sound and the voice. To me, Jean’s work seemed like sound waves that told stories. We started thinking about what we could do together, and that was when we came up with O/AURAL WAVES. The title references both the oral waves that are central to my practice, and the aural waves Jean works with.

I don’t know much about foleys, but to me, it is about the imagination. If I want to tell a story about a gravedigger in a cemetery in the midst of a thunderstorm, chanting and reciting incantations whilst digging up a virgin’s grave, ripping out her liver, her kidneys and her lungs — how can we make the audience feel this macabre experience behind their neck, under their knees, or by their side? We spoke to The Arts House about doing an installation during Textures, and I wanted Irfan Kasban to turn the entire space into something inspired by the selected texts.

When audiences walk into the dimly lit installation wearing wireless headphones, they don’t even know where I’m seated. There are no designated seats for audiences either. They have to sit within the installation itself. You’d begin to hear things, but you can’t see anything because the foley artists and Jean are concealed within the furniture. A light is then turned on, and the audience sees only my silhouette. Immediately, they get the sense that this isn’t an ordinary storytelling experience. Was the story scary? I don’t think so. Was my storytelling scary? Not any more than it usually is. What made this entire experience so mind blowingly scary? It was the combination of my voice, the installation, the foleys, and the fact that everything was done live.

Jean and I are working on another iteration of O/AURAL WAVES for 2021. It is the marrying of technology with storytelling, and even if one comes back for the second or third time, the experience will always be different. I am still speaking live, and the foley artists are still ripping and shredding things live. That’s where the authenticity is with O/AURAL WAVES. It’s not fully scripted or choreographed. Jean and I are part of an orchestra, but there is no conductor. Everything hinges on listening.

⁹ Sunflower Seeds, Ai Weiwei

2010, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

Ai Weiwei’s work, Sunflower Seeds, features what seems to be a mound of ordinary sunflower seeds. For the National Gallery Singapore’s ‘Stories in Art’ programme, you told stories that drew upon this work of Ai’s. How do artworks serve as springboards or entry points within your creative process, and how do these stories then feed back into deepening an understanding of these works?

I’ve always felt that museums, artefacts, galleries, artworks and objects all contain narratives within them. This could be stories about how it was made, the materials used, the particular style of craftsmanship, or the maker themselves. Traditional artworks — be they scrolls, paintings or carvings — often contain depictions of mythologies or cosmologies. I love using art as a springboard. I also enjoy telling the stories of artefacts that might not be considered works of art, but are cultural or heritage objects. I started telling stories that were clearly embedded in certain mythologies. For example, the Asian Civilisations Museum has a set of emperor's robes in its collection, and on the robes are a certain set of motifs. Certain motifs, such as tortoises or cranes, can be used to segue into any Chinese mythological story.

The National Gallery Singapore, on the other hand, posed an interesting challenge. It was no longer about traditional Asian depictions, and I had to think about the sort of connections I could make. The whole point behind these 'Stories in Art' sessions was to get families to visit the gallery, and to make the visual arts accessible. For Sunflower Seeds, I began by talking about the work itself, particularly the fact that these seeds were made of porcelain and individually. After that introduction, I went into a story about an emperor who was looking for an heir to the throne. He wanted to test all the children in China, and he gave every child a seed to plant. The children were told to come back in a few weeks, and to present the grown fruit trees or flowering plants to the emperor then. A few weeks passed and every child came back with beautiful plants, except one boy. No matter how he tried, nothing would grow. Of course, the emperor chose this particular boy as his heir, and this was because he had been truthful. Prior to giving the seeds out to the children, the emperor had boiled them all. The seeds were all dead, and so they couldn’t have grown into the beautiful plants that were presented to the emperor. The sunflower seeds in Ai Weiwei’s work didn’t have any particular story attached to them. It wasn’t a carving of Hanuman or a batik remnant. It was up to me to find the connection, and this activated the artwork in a way that anecdotal or statistical information cannot. Though it seemed like a simple engagement, it was one of the most challenging long-term projects that I've worked on. I had to think very deeply about the connections between the story and the artwork, and between the artwork and its own story.

Outside of the context of the National Gallery Singapore, I also enjoy using a lot of visual cues. Over the years, I've evolved beyond just telling stories using my voice. I'm beginning to incorporate some visual richness into my sessions. I find a lot of pleasure in setting up an altar, a rangoli, or bringing in some peacock feathers, or a piece of fabric — all of these objects lend something visual to the story I'm telling. I'm settling into a different phase of my practice where it's site-specific, monument-based, and roving. This has become a bit of an obsession for me in recent years. I find a lot of pleasure in doing this because it creates a very visceral experience.

I've come to a place where I'd like to incorporate some visual richness into my sessions. I find a lot of pleasure in setting up an altar, a rangoli, or bringing in some peacock feathers or a piece of fabric — all of these objects lend something visual to the story I'm telling.

¹⁰ The Seed, Kamini Ramachandran

2019, Performance at the National Gallery Singapore

¹¹ The Seed, Kamini Ramachandran

2019, Performance at the National Gallery Singapore

2019, Performance at the National Gallery Singapore

¹¹ The Seed, Kamini Ramachandran

2019, Performance at the National Gallery Singapore

Decoloniality is a long-term struggle for land return and against European imperialism. The fact that we’ve lost touch with so much of our heritage can be attributed in no small part to the British colonisation of Singapore and in a previous conversation we had, you referenced how myths and legends have been subdued as well. Within that context, storytelling can be seen as a decolonial exercise. In your opinion, what sort of nuances can the telling of stories add to this conversation?

The telling of stories is a decolonial exercise — there is no doubt about that. I’ve never openly or consciously stated that because it’s something that I want people to realise over time. It’s similar to how I don’t have a moral lesson at the end of every story, even when I’m telling stories to children. I believe that when a story is told well, a child does not need a conclusive moral ending in order to learn something from it. This quiet way of telling Asian stories, and telling it without sanitisation, has been my small way of contributing to this movement.

Early on in my career, I had a terrible experience with an American storyteller-editor who was putting together a compilation of Asian folk tales. I submitted a traditional Malay folk tale about a fool. There are characters such as Pak Pandir and Pak Belalang who, through the troubles they get into, realise that there are certain things that they should or should not do. A lot of these traditional folk tales are violent, simply because they were warnings and told as cautionary tales. If you remove the violence from these stories, why would anyone be scared? I grew up hearing these stories from Malay cikgus. To then see them sanitised, or to see “happily ever after” endings slapped onto them, was very upsetting.

I’ve told stories in venues such as The Substation that really left people thinking, “Wow, folklore has a lot of sex, a lot of violence, a lot of pillaging, and a lot of plundering.” But that’s our society today as well. We are still surrounded by violence, corruption and disasters. Nothing has changed, and we should tell these stories the way they were meant to be told. We don’t have to package them nicely or tie them up with a ribbon. We’re not doing audiences any favours by simplifying these stories or cleaning them up.

One of the stories I’ve told is Tell It To The Walls, a story from South India. It is about an elderly lady who lives with her two sons, her daughters-in-law, and multiple grandchildren. She has no one to talk to because everyone is so busy, and at the end of the story, she leaves the family home. She finds herself in an abandoned house that’s completely derelict, except for its four walls. She looks at each wall and she cries, screams, and yells, hammering out her pain, her anger, and her sadness. One by one, the walls crack, crash, and fall to the ground. There is catharsis, and she now feels better. This story has three different endings. The first is that she goes home happy, and continues staying with her family. The second is that she remains in this house, and makes a new life for herself. The final ending, and the one I like to tell, is that she continued to walk on, and that she is still walking now. Oral traditions don’t present things in a clear or neat manner. Storytellers have been known to give their listeners options when it comes to a story’s ending. This is not something you see in print or in movies, but is something that gives power back to the story. Earlier in our conversation we spoke about this Western impulse towards analysing, compartmentalising and categorising. That is how the West is used to arranging and presenting their culture and their narratives. In the East, however, things are a little more fluid and ambiguous. As a storyteller, I’ve done my part in presenting the story to you. It is now up to you in deciding how this will end.

I’m also invested in telling and retelling lesser-known Asian stories. When I first started out, I’d get questions as to who Badang was. Now, more people know about his story and the Singapore Stone — which is said to be the stone Badang threw, and is now in the collection of the National Museum of Singapore. It takes a long time for these shifts to happen, and it’s about consistently telling these Asian stories over and over again. This consistent practice is my way of going against a narrative that presents folklore and fairytales as only consisting of stories such as The Little Red Riding Hood and Goldilocks and the Three Bears. I love those stories and they shaped my childhood, but it’s important that we add in a good sprinkling of Asian folklore as well. It’s not just about Western stories.

Oral traditions don’t present things in a clear or neat manner. Storytellers have been known to give their listeners options when it comes to a story’s ending.