Kelly Limerick is the pseudonym of Singaporean-born artist Kelly Lim (b. 1991). Having first picked up crochet in 1997 when she was seven years old, Kelly then taught herself knitting, and has since been using both skills for her artworks. Kelly often creates without a sketch or set patterns to produce one-off designs. Her work includes elements of kimo-kawaii (きもかわいい) — a Japanese term meaning grotesque-cute — and focuses on textures and details. Recently, she has been exploring large-scale installations, which inject unexpected visual impact in urban spaces and aim to provide immersive experiences by engaging the site. Much like a living creature, her art ‘grows' with new inspirations every single day.

Kelly’s works are known for their imaginative quality, and for a perspective that presents an almost pure, childlike wonder. Creating primarily with crochet and yarn, Kelly’s works range from small creatures that can be held in ones hand to large scale installations that viewers are allowed to walk through. For our conversation, Kelly picked out a selection of ideas, objects and artworks that have inspired her practice and way of seeing.

Kelly’s works are known for their imaginative quality, and for a perspective that presents an almost pure, childlike wonder. Creating primarily with crochet and yarn, Kelly’s works range from small creatures that can be held in ones hand to large scale installations that viewers are allowed to walk through. For our conversation, Kelly picked out a selection of ideas, objects and artworks that have inspired her practice and way of seeing.

¹ Silver Leaf

Credit: Kelly Limerick

Credit: Kelly Limerick

Much of what you’ve picked out for our conversation today revolves around nature, and that’s something that comes through in the images you use in your works and your personal interests as well. How would you describe your relationship to nature, and how do you see that seeping into how you approach your practice?

If you go through my portfolio and look at what I’ve done, I don’t think the link to nature is immediately evident. I’m still in an explorative phase in my practice, and I only started discovering what I liked about nature about three years ago. I remember it very clearly. I was doing volunteer work with the Setouchi Triennale, and that was my first time seeing art surrounded by nature. Before this, I had never thought art could be seen like this. My background is not in fine art, and I hadn’t been exposed to such ideas before. Like a typical Singaporean, I thought art had to be displayed in a gallery. I knew nothing about art in white cube spaces, and it felt like a very separate world to me.

I decided to go for the Setouchi Triennale because a friend of mine, knowing my interest in Japan and Japanese culture, recommended it. At that point in time, I was at a crossroads with my own life — I wasn’t really sure what to do next. Going to the Triennale was an eye-opening experience for me. We have nature in Singapore, but it is a very manicured version of nature — manicured to the point that it almost feels sterile. We don’t really know what nature is, and most of us aren’t able to name the exact species of plants we encounter everyday. However in Japan, I realised that my hosts and friends were able to identify what a chestnut or an oak tree was. They would reference certain plant species in conversations not because they wanted to be hipster, but because they knew the exact characteristic associated to that plant. For example, they’d know which trees have wider crowns that provide more shade, or trees that only grow in a specific part of Japan. We’re so out of tune with our natural environment here in Singapore, and that was something that really dawned upon me when I was in Japan.

It started to draw me in, and I started thinking about my art very differently as well. Prior to this experience, I had already been creating soft sculptures under my Creatures series. I’ve always been interested in Japanese monsters and yōkai, but these earlier Creatures were primarily explorations into textures and colours. After my participation in the Setouchi Triennale as a volunteer, I started to think about what more I could do with my work. I’ve only recently started thinking about how my relationship to or thoughts about nature can be expressed.

² Aegir, Kelly Limerick

2019

³ Mr. Reef Walker, Kelly Limerick

2016

2019

³ Mr. Reef Walker, Kelly Limerick

2016

Setouchi Triennale is known for including artworks that are monumental, grand and interactive. Over the years, you’ve worked to create quite a few site-specific works that are quite large as well. This is clear when we look at the work you did as the artist-in-residence at Facebook or at Fort of Leaves with OH! Open House. They bring to mind a quote by Isamu Noguchi, “Art should become as one with its surroundings”. Is this expansiveness something you set out to achieve with such works? If so, why is it important to you that they envelop the viewer so?

When we think about the works made for the Setouchi Triennale, we have to remember that the artists did not create these works alone. Making my works, in comparison, is a rather solitary activity. Artists in Japan often work collaboratively with each other, and they often work with the community as well. This allows for them to assemble really huge pieces of work. When I made Fort of Leaves, I had the help of just one assistant. Although I managed to enlist the help of three other people with spinning the yarn for the work, it was still a stretch.

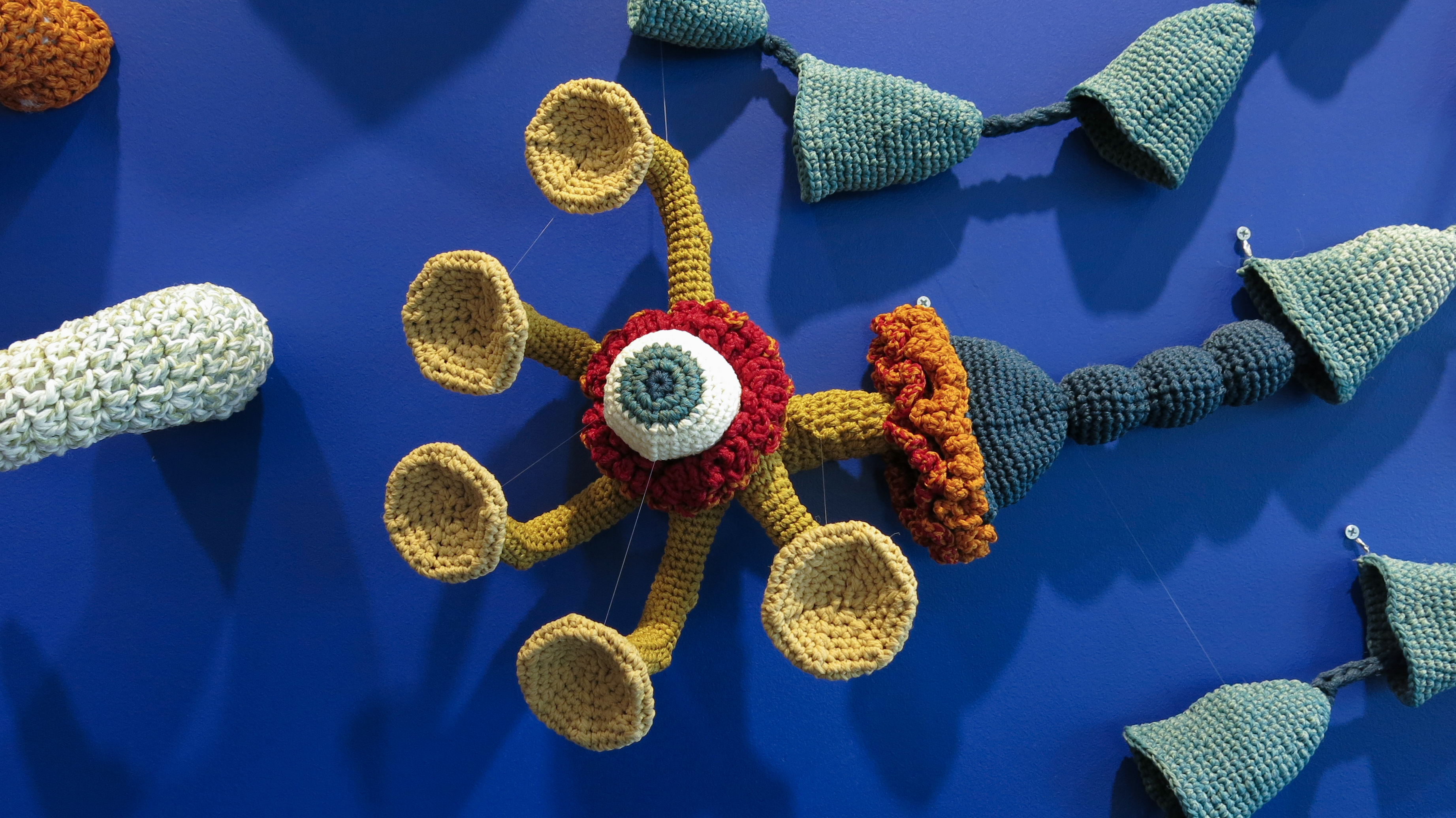

At this point, it’s rather difficult to say for certain because I feel like I’m still exploring. I would say that the work that I made for the Facebook APAC HQ, Radiolarian, isn’t even that immersive. For starters, the work is installed onto a flat wall. Even though the work was meant to be site-specific, it was installed onto a different wall to the one I originally conceptualised the work for. Because of that, it became all the more evident to me that a wall is, simply, just a wall. If a work can be moved away or travel from its original setting, then perhaps it wasn’t as site specific as it was touted to be. Site specific works are very special to me because they were what drew me towards making art in the first place, so this is still something I’m working on.

⁵ Fort of Leaves, Kelly Limerick

2018, Installation View at Bras Basah Complex

2018, Installation View at Bras Basah Complex

It’s interesting that you talk about the collaborative aspect of creating larger artworks both in the context of your own practice and with regard to how the artworks you encountered at the Setouchi Triennale were like. You spoke about how artists would work with the community for the Setouchi Triennale, and I was wondering if you could expand on that a little more?

On the other hand, I find it difficult engaging help for my projects. Maybe I’m picky, but not many people in Singapore know how to do crochet either. Personally, I didn’t graduate from a fine arts school myself. That makes it harder for me to tap on an existing base of students or alumni for help as well. Last year, I finally worked on a project that successfully engaged the community for the Asian Civilisations Museum. I worked with more than seventy volunteers for this project. This all started with a private Facebook post I put up on my personal account, asking for help on this particular project. A friend of mine saw that and reposted it publicly, and somehow word about the project eventually reached a crochet and knitting Facebook group. I didn’t even know this group existed, but there were a lot of crochet enthusiasts on the group. They got together, compiled Excel sheets, and organised themselves into various groups. I was completely overwhelmed by just how many people expressed interest, and that’s when I found out that such collaborative activities are quite common for the crochet and knitting communities here. They often meet up to make blankets or beanies for underprivileged children as well. Initially, I was really worried as to how I’d split my artist’s fee amongst seventy knitters, but they assured me that they just wanted to contribute to this and they didn’t need remuneration. When the final work was unveiled at the museum, these volunteers came down with their families and were able to point out the parts of the artwork that they had made.

I insisted that these volunteers be credited in the artwork label, and this was something I learnt from being at the Setouchi Triennale too. Sometimes, people just want to be a part of something. The museum staff said that the label was too small to include all of their names, but after I pushed for it, all seventy names were on the label — albeit in a very small font. This project probably wasn’t the most artistically creative, but my takeaway from this project was the fact that I was able to involve this group of people in creating a work like this. I think it was a process of discovery not just for myself and the volunteers, but for the museum as well. The Asian Civilisations Museum is known for their collection of historical artefacts, and they’ve just put on a show of Guo Pei’s works as well. To include a work like this in their foyer is a huge step for the museum in bringing the community in.

⁶ Portal of Patterns, Kelly Limerick

2018, Installation View at Asian Civilisations Museum

Full volunteer list can be found here

2018, Installation View at Asian Civilisations Museum

Full volunteer list can be found here

Crochet is a medium that many associate with hobbyists and craft. Despite that, you’ve consciously approached your practice as an art form. What does being a crochet artist mean to you? Do you define this by differentiating clearly between crochet as craft and crochet as art?

This is such an interesting question for me, because I had a conversation with my assistant the other day that relates to this. My assistant is older than me, and about forty years old this year. She wondered why just about anyone and everyone was calling themselves an artist nowadays. She’s right. Everyone’s an artist nowadays. The customer service staff at Subway are sandwich artists.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to define what an artist is, and this is something I grapple with myself as well. Am I an artist?

I’m still not completely sure.

For me, there is a difference between crochet art and crochet craft. Everyone who does crochet starts off by using patterns. There are millions of free patterns online, and we all start with them in order to practice and improve on our technical skills. I started doing crochet when I was seven. By the time I was sixteen, I was bored of all of these patterns I found online. Some of them got rather repetitive, so I started creating my own original stuff. So I would say that the first step is following patterns, and the next step is creating your own patterns. Some people never get past the first stage because crochet is a rather therapeutic craft for them. They do it to pass time or when they’re feeling stressed. If I wanted to make a figure of Spongebob, for example, but could not find a pattern for it, I could make my own based on the technical know-how I already have. That’s when I’ve gotten to stage two — creating my own patterns. Yet, I still won’t consider that doing art just yet because Spongebob isn’t a character you’ve created. The next stage would be to create something that’s come completely from your own imagination. A lot of the people who call themselves crochet artists have reached these level in their practice.

Beyond that, I think there’s still another level to this. The question here is if you make a piece, and someone pays you to do replicate it, would you do it? At the end of the day, art is a business and there is money is involved — as much as we hate admitting it. You don’t make something with money in mind, but money is a form of remuneration for the time and effort you put into making something. So when I talk about this process, I’m referring to whether someone can dictate your artistic voice by throwing money at you. I think that being an artist means being able to decide one’s ideals for oneself. You shouldn’t be doing more or doing less in order to fit into someone else’s ideas, much less be dictated by them. This is where I’m at at this point in time. I’m sure it could change in time, but this is how I understand this definition now.

Let’s come back to your selection and how it relates to your works. Some of the works in your Landscapes series were recently exhibited in The Substation’s Rejects showcase. With these works, we see dolls being subsumed into layers of soft and plush yarn — much like the creeper plants you’ve been inspired by. As you turn your attention towards creating landscapes out of tactile yarn, how do you balance various factors such as colour, texture and meaning without them subsuming each other?

I’m not sure how I can answer this question, because I’m of the unpopular opinion that my art doesn’t have a deeper meaning. Of course people could say that if that’s the case, then what’s the art for? The art has to say something.

When I first started out as an artist, I did a lot of yarn bombing. A lot of this was underscored by a desire to be noticed. I wanted to inject an element of surprise into the spaces that we walk by everyday. I still stand by what I did then, but I think I’ve evolved since. I don’t want to provoke people just for the sake of it. Over the years, I think that side of me has mellowed out a little. There are artists today who create works that are, for example, very politically charged. There’s nothing wrong with that, but that’s just not my style. With social media and the pace with which we consume the news today, I wanted to provide an antithesis to that. In a sense, I think my art can be considered a kind of slowing down.

Having said that, I know that people sometimes look at my pieces and are unsure of what they mean. I wouldn’t say that these works are abstract per se. I’m not trying to communicate anything in particular, and I want viewers to dig deep into their own emotional response when they encounter my works. When they look at something I’ve made, what comes to mind?

I want to turn the conversation back to my experience in Japan again. The Internet is full of images of popular tourist destinations in Japan. Most of us are familiar with how, for example, Mount Fuji looks like. Yet when you’re there, face to face with the mountain itself and seeing it in person, you realise just how limited a photograph is in conveying an experience. There’s the biting cold wind, the journey up to the viewing spot, and the surrounding scenery. Coming face to face with nature is always a humbling moment, and in it, there’s always something to be learnt about yourself. This is something people try to achieve through meditation, and this feeling is also what I enjoy about practicing yoga myself. For example, if one set out to paint a landscape, it goes beyond just portraying a beautiful scene. As your paintbrush or your pencil traces the outline of a mountain, you are touching it with your own fingers. That’s the beauty of art — the fact that you get to touch it.

When I work on my Landscapes works, I’m recreating these scenes that I’ve seen on my travels. I take photographs of these sights I see, but I try not to refer to them when I’m making these works. Sometimes when I’m done with a work and I compare them to the photographs I have, the two look completely different.

In my mind, I always have an image of the places I’ve been to and that’s what I tap on to create these works.

Crochet is very slow work. I spent close to three months creating those two works in the Landscapes series. It was entirely spontaneous, and I didn’t have any drafts or make any drawings. I went onto Google Maps and traced out the contours of the island itself. That was what I used as the base shape for these works, but the rest of the work was free form. These Landscapes grow with me, and this is something that runs across all of my works as well. It is the same with the Creatures I make — I don’t do drafts, and I just go into it intuitively. If people see some of my emotions woven into the work itself, that’s great. But if they don’t, that’s completely fine as well.

Prior to this, I was reading a previous interview you guys did with Khairullah Rahim. In the interview he said, “Art is for anyone, but it’s not for everyone.” I totally agree with him. He was talking about having an intention when you create art, and I think that’s important but perhaps I approach this from a slightly different angle. I don’t have a specific audience in mind when I make a work. I’m just trying to express what I feel at a particular point in time. I’ve been moving towards creating pieces where I’m playing with textures and colours. In terms of what they mean or a message, I don’t have something set in stone.

⁷ I Walked A Landscape With My Fingers: Baby, Kelly Limerick

2019

⁸ I Walked A Landscape With My Fingers: Drown, Kelly Limerick

2019

2019

⁸ I Walked A Landscape With My Fingers: Drown, Kelly Limerick

2019

I wanted to elaborate on how you described tracing out the shape of islands for these landscapes. Something else you’ve been inspired by is the idea of islands, and this is something you wanted to focus on for our interview as well. Islands are liminal spaces, and they hold particular intrigue for artists and creatives based in Southeast Asia. Tell us more about what attracts you to the notion of islands, and what immediately comes to mind when you think of an island.

We all know that Singapore is an island, but I’ve never seen it as such because we’re so connected to the rest of the world. When I think of an island, I think of somewhere that’s completely disconnected. If you think of what an island means geographically, of course Singapore is an island. Yet if we’re thinking about this on a conceptual level, I don’t really think Singapore is an island.

Setouchi in Japan, where the Triennale is held, is a region surrounded by the Inland Sea. There are probably a hundred smaller islands in this region, but the Triennale only spans across a few of them. Before I travelled to this region, I didn’t know about the Triennale at all. The first island I arrived in was Awaji-shima, and it’s a pretty big island. Before we started doing land reclamation here in Singapore, we were actually about the same size, in terms of land mass, as Awaji-shima. Despite that, they have a population of around 10,000 people. When you compare that to our population of six million people and how densely built Singapore is, you can imagine the amount of free space that the people of Awaji-shima have on the island. It made me think about how it would have been like for Singapore if we had not been modernised.

The second island that I visited in the Setouchi region was Shōdoshima. When we were in our ryokan, we noticed a large disco ball structure on the pier from our window. It really took us by surprise because the structure was rather out of place in an otherwise tranquil and quiet island. We went down to the pier to see the structure, and it was there that we met an old man who informed us about the ongoing Setouchi Triennale. He offered to take us around the island for free, and my friends still think I’m crazy for agreeing to this, but we accepted his offer. The majority of the population on the island are elderly folk who, on a day to day basis, don’t have much to do. Having foreigners visit them is something that’s really exciting for them, and they are always really eager to share their homes with us. We went around and saw some really interesting works, including one that was set in the middle of a forest. I never expected to experience art like that on a small island in Japan, but it really got me thinking.

When I think of an island, I think of this idea of being completely disconnected. Singapore is known as a place that people come through when they are in transit, enroute to somewhere else. We’re connected to Malaysia, for example, by bridges. It is so easy for us to travel in and out of Singapore, and no one really thinks about the journey. The journey is always of utmost importance. When we journey somewhere, like an island, it gives you an emotional lift. When you get onto a ferry and leave the mainland, it really feels as if you can let go of your troubles — even if just for a moment. We watched the sunset on the sea everyday when we were in Setouchi. It is such a nice experience, and it made me realise how we sometimes make such a big deal of watching the sunset. We prepare picnics, take photographs of it, but then when we pack up to go home, we forget about the fact that this is a phenomenon that happens every single day. When I was out there on the sea, heading back to shore, certain things would strike me. I’d wonder about how waves are formed, or what the colour of the sun is. These things are around us everyday, but not all of us think about or question how they work. In the middle of the sea, you realise just how small you truly are. Yet, you feel as if your spirit has been lifted and is expanded. I explain it to my friends by saying that the world is too big for my worries, and too small for my dreams.

⁹

Radiolarian, Kelly Limerick

2019, Installation View at Facebook APAC HQ

2019, Installation View at Facebook APAC HQ

You touched on how emotive or intuitive your processes are earlier in this interview. Your Creatures are some of your best known work, and no two are the same. Given that each Creature is unique, what connects them to each other as a series? Do you approach the conceptualisation process for each Creature differently?

Every Creature is very different. When I start making a Creature, I always start by thinking of who the piece will be made for. I try to get to know this person as much as possible by asking them questions such as, “What do you like eating?”, “What’s your favourite colour?”, or “What are your hobbies?” I don’t provide them with sketches beforehand, and I never have a plan. A lot of it depends on how I feel at the point in time that I’m making the piece. Every piece grow with me. Some of them take a week to finish up, and others, a couple of months. It all really depends. Sometimes when I’m feeling uninspired, I’ll leave the piece to the side for awhile until something strikes me. It could literally be as simple as thinking that the Creature would look quite nice with a tail because a saw a long-tailed cat on my way home earlier that day. So every Creature really is a rojak of all of the experiences I had over the period of time I’m working on it. The stories that accompany the Creature and its name only comes to me much later. I know that a Creature is done when I sit back, look at it, and realise that it has a character. That’s when I know it is time to name the Creature.

I think this is what bothers me when I say that my art is not deep enough. Everything I make stems from my own feelings.

I’m not trained in fine art, and sometimes I think it’s both a good and a bad thing because often, I don’t overthink it.

When I think about the distinction between an artist versus an artisan, sometimes I don’t really know where to place myself. Of course, I create original work and am an artist. However, craftsmanship is a really important aspect of my work as well.When you think about things like ukiyo-e, there’s often at least three people involved in the process of making such a print. There’s a designer, a woodblock carver and a printmaker. When the print is made, everyone is given equal credit for the product. Yet, we tend to see a very distinct difference between the role of an artist and a craftsman.

2013

1968

You’re currently in the midst of working on a project that looks at the use of plastic through the angle of art. Art often has a pulse on what’s happening at the moment, and often in doing so, is created in response to socio-political developments. Obviously art is only a small piece in what is a global problem, but as someone who is working on this now, what do you think art can bring to these conversations?

I think there’s always a danger of jumping onto the bandwagon of “trendy” topics. Some artists have started creating works in response to something like climate change just because that’s the hot topic right now. Intrinsically, I’m not sure if everyone truly believes it. In Singapore, I think this is really evident in the way in which education is lacking for the general public. When somebody does something wrong, they are fined. When someone does something right, they are rewarded. The system isn’t set up to encourage deeper thinking. When it comes to the whole green movement, people could be using their reusable cups or metal straws but still purchasing things from Taobao in bulk. If you truly believe in a value, you have to embody it.

I’m working on a project with plastic now because the client initially wanted to work with yarn spun out of recycled t-shirts. I’ve worked on similar projects in the past before, and in my experience, it often is quite difficult to execute. You’ll have to get volunteers involved, go down to a recycling drive, sort through the shirts and spin the yarn. Often, volunteers find that too tedious and end up buying new t-shirts instead, which completely defeats the purpose of the project. A friend of mine had just moved into a new place, and they were unwrapping all kinds of furniture. Everything was packaged in plastic, and there was plastic everywhere. Just on a whim, I decided to cut these plastic wraps into strips and I knitted them into a wastepaper basket. That was really where the idea for knitting with plastic came about. I did an open call online, crowdsourcing for plastic. Unfortunately, I couldn’t collect enough plastic for the project. Ironically, we ended up buying the plastic. However, we purchased the plastic from a recycling plant that collects this plastic waste from industrial factories. I have to admit to this because we were pressed for time as well.

At the end of the day, the whole entire process was quite organic. We didn’t start with the idea of working with plastic because it was timely or trendy. It came through something I encountered just by being out and about. I always draw upon the things that happen around me for inspiration.

This whole entire consumerist mindset is so deeply ingrained into all of us, and it happens even with art as well. Right now, the yarn I use is 100% recyclable. 3D printing, as you know, is the new fad. When people tell me that they are thinking of purchasing a 3D printer, my first question to them is always, “Are you creating trash?” In this day and age, you really need to think about what your art is doing. If your message is strong and you know that the art is important, then go ahead and use the resources you need to make that work. But if it’s a short-lived piece that is only used for one event, it will most probably go into the trash after it has served its purpose. This is also why I stopped yarn bombing. Yarn bombing always creates a lot of waste, and you’re always unsure as to what to do with all these pieces you’ve made.

Having said that, I came across an artwork that doesn’t pursue longevity. In fact, it was created to be ephemeral. That was what drew me to Yamamoto Motoi’s work when I first met him in 2016. Saddened by the loss of his sister to cancer, he wanted to commemorate her without grieving over the loss forever. He created an artwork made entirely of salt, and this work was to be destroyed and returned to the sea after the exhibition concludes. I thought that was beautiful and perfectly symbolised the Japanese term, hakanasa, which loosely translated means fragility. It is often used to describe fleeting moments, like a flower in bloom. This zero-waste artwork had such a strong impact because viewers knew it would only be there for a limited period of time. His art led me towards works such as Phase—Mother Earth by Nobuo Sekine, which symbolises humans just ‘passing through’ the earth. I think this should be direction that art moves towards in the face of climate change. It is a goal I hope to achieve as well, though it might prove difficult with my medium of crochet.

¹²

Hetty, Kelly Limerick

2017

¹³ Daiki, Kelly Limerick

2017

2017

¹³ Daiki, Kelly Limerick

2017

During a previous conversation we had, you spoke about how you’ve been grappling with the various labels of being an “artist” and being an “influencer”. This seems to be a dilemma that many artists are facing, especially given the role social media plays in our lives today. Why do you think there is this resistance to the artist as influencer, and personally, where are you at with reconciling these different facets of your practice?

Often, influencers are also working to get more likes on their photos or their posts. I’m currently reading a book by Adam Alter titled Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked. It talks about how social media actually taps on a very primitive part of our brain, and we get dopamine kicks from receiving validation online. It’s an endless, vicious cycle and the likes will never be enough. There is no point to it. When Instagram introduced the Stories function, I noticed that people were taking to social media to ask for advice on simple day-to-day decisions. People would crowdsource for opinions on matters such as hair colour, asking questions such as, “should I dye my hair blue or pink?” It felt really warped to me because at the end of the day, you’re being controlled by all of this feedback.

This really goes against what I believe in or value as an artist. The reason we have art in this world is to create discussion or to encourage debate. Not everyone’s art is created with a political stance, but all artists create their works in response to something. That response cannot be and should not be influenced or swayed by the general public. When people call me an influencer, I don’t feel offended but I do feel like I need to educate them. Having said that, I’ve had my difficulties with this too. I think when everyone points their fingers at you and calls you an influencer, you can start to doubt yourself as well. My friends have also called out the fact that I post a lot of selfies on Instagram, and that these selfies make it hard for anyone to take me seriously as an artist. People associate me with my looks, my makeup and even my dreads. It was tiring because I was grappling with whether to dress a particular sort of way in order to fit that impression. It got to a point where I realised that my art should really just speak for itself. It was only when I spoke to a friend, who helped me realise that being able to embody my art is an advantage of mine, that I decided to just move ahead with doing what I wanted to do. I don’t wear my dreads for attention. I do it because I feel like it. I dress up when I feel like it.

Being an influencer feels very unnatural to me, and that’s not what I want to be.

Social media is a game. If you choose to play it, you can and it can be helpful. I have to be honest, it has been helpful for me and my career. However if you don’t, that’s completely fine too. I’m really hoping that I can get to a place, one day, where I no longer have to be on social media anymore.