Lee Chang Ming is a Singaporean photographer interested in themes of intimacy, gender identity, youth and the everyday. His practice contemplates the subjective act of looking and the photographic medium as a process. He is also the founding editor of Nope Fun, platform that features photographers and artists from all over the world.

Chang Ming had a busy 2018. The past year saw his works being exhibited internationally, and his participation in various art book fairs as well. To kick off our interview, Chang Ming chose the theoretical works of Roland Barthes, the cinematic images of Wong Kar-Wai, and the photo books of Eiki Mori and Wolfgang Tillmans. To accompany this interview, he has put together a playlist for our readers to listen to whilst reading.

Chang Ming had a busy 2018. The past year saw his works being exhibited internationally, and his participation in various art book fairs as well. To kick off our interview, Chang Ming chose the theoretical works of Roland Barthes, the cinematic images of Wong Kar-Wai, and the photo books of Eiki Mori and Wolfgang Tillmans. To accompany this interview, he has put together a playlist for our readers to listen to whilst reading.

Prior to this interview, you mentioned being drawn towards not just artworks and art objects, but theories as well. This has really come through in your eventual selection for this interview. Tell me more about what was going through your mind when picking things out for this interview, and why this mix?

I wanted to pick things that have influenced me, and things that I have an emotional connection to. In particular, I picked out things that I found very affecting. In the end, the works that I picked out are works that I have always felt connected to. I wanted to figure out why I had this response towards or this resonance with them. As a photographer, I also wanted to see if there was a particular sort of vocabulary that I could use to describe the visual language both in these works and in my own.

When I first started thinking about things to choose for this interview, I wanted to pick out some songs. My work deals with a lot of personal themes, be they personal situations or emotions. For me, songs capture that feeling I get when I look at something or hear something.

That’s really interesting — because you feel a particular sort of way when you hear music, but you try to replicate that feeling through visual means instead.

I think one can definitely tease out one’s emotional response to anything — be it a visual or a song — and try to reflect that experience through a different medium. I didn’t choose any music in the end because I couldn’t pick out one artist, or one album, or even one song that would directly relate to my work. In that sense, I suppose music is more of an inspiration or an indirect reference to what I want to do with my own work.

¹ Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes

Let’s start with your pick of Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida. It’s a text that is seminal to the study of photography, yet it speaks almost nothing of photographic technique or theory. Instead, it reads more like a eulogy for Barthes’ mother. Many photographers have cited this work as foundational to their practice, but how do you personally relate to that text?

I was very drawn to the first half of the book, especially when Barthes spoke of how photography worked as an entire process. It’s not just a matter of pressing the shutter, but it’s also the cultural context within which a photograph is taken, and how it is then shown. The viewer plays an important role in determining how the image is viewed. Barthes wrote about the studium and the punctum in this book. You have the image — whether it be pixels on a screen, or ink on a book — and you have the referent, which is what the image refers to. Looking at that referent, sometimes one can develop an emotional response. That response is what Barthes refers to as the punctum.

I thought that was really interesting, because he articulated something that had always been at the back of my mind. Many photographers aspire towards creating a work that goes beneath and beyond what’s shown in an image.

Barthes notably categorises the cultural context within which an image is made and the emotional response a viewer had to it separately. This is more an open-ended question because everyone else has a different perspective on this, but do you think that the emotional responses viewers have to the images you make can be seen as separate from the cultural context within which you operate?

I get a very different responses to the same body of work when its shown overseas. For example, I worked on a project titled Until Then, which was quite specific to the context of Singapore. I had the opportunity to showcase works from this project in Kuala Lumpur, which is similar in many ways to Singapore but still distinct. Because of the differences in our cultural contexts, the response to the project was very different. Hearing these responses was interesting for me, because the same images were being displayed. Yet because they were now being shown to different communities in different spaces, they related to these images differently.

Everyone responds to images in relation to their own perspective — and I’ve always found that very interesting.

I think that relates to the notion of the punctum, because it no longer is just about the work itself. The viewer’s response is just as significant. I also find these different perspectives incredibly refreshing. Usually, these conversations bring up something I hadn’t even considered before. In turn, it adds to my own understanding of the work as well.

When I first started showing my work, it was very much through online platforms such as Flickr and Tumblr. When you put an image online, you have very little control over where it goes or how it is used. Anyone can save a copy of the image onto their computer, use it as their desktop wallpaper, or manipulate the image however they like. That’s just the reality of it, and there’s nothing one can do about it. I find it interesting that when a work is placed online, the artist eventually has to divorce him or herself from the work.

² Until Then, Lee Chang Ming

2018

2018

³ In the Mood for Love, directed by Wong Kar-Wai, and starring Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Maggie Cheung and Siu Ping Lam

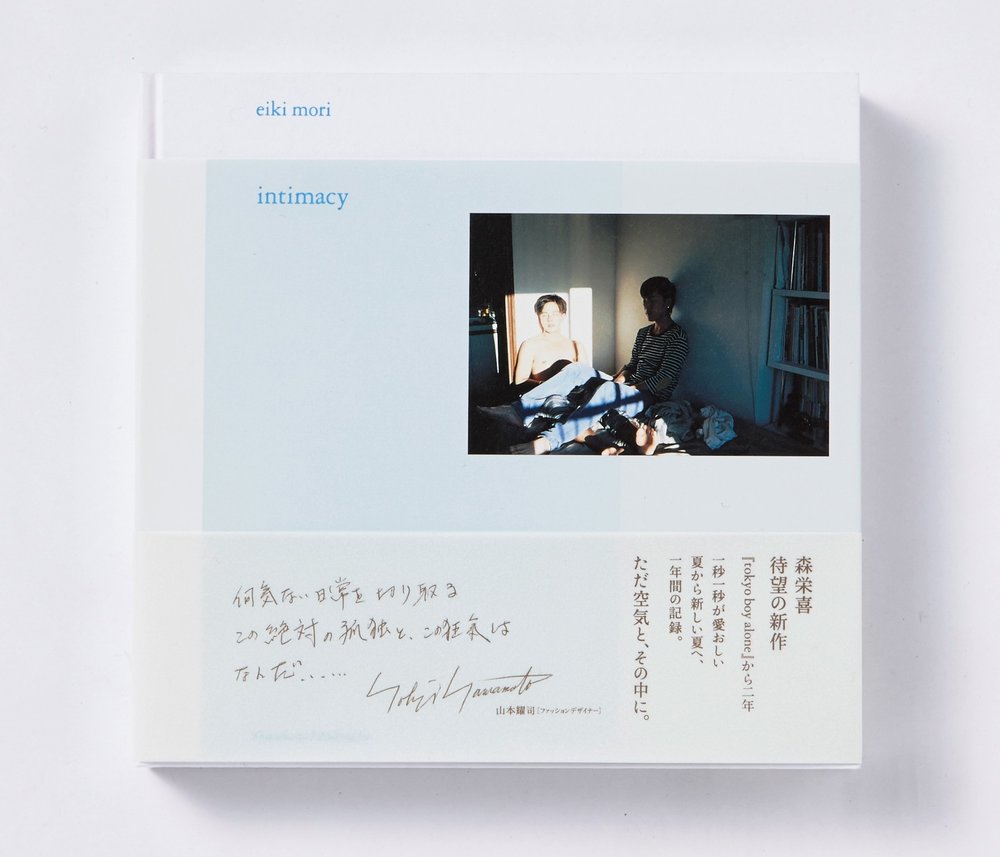

⁴ Intimacy, Eiki Mori

Two of the works you chose for this interview, Intimacy by Eiki Mori and In The Mood for Love by Wong Kar-Wai, have mastered the use of body language and movement as a means of referencing emotions that lie beyond the frame. It really brought your project, Until Then, to mind. Did these two works have any bearing on how you approached that project, and if so, how did they help form your approach towards photographing something as intimate and personal as love and identity?

With Wong Kar-Wai’s In The Mood For Love, the movie is about longing, desire, and a relationship that tethers between existing and not existing. I enjoyed how he used cinema — the use of colour, the lack of dialogue, the use of music, and using reflections as a device for indirect glances — to communicate these ideas. He managed to use an overall atmosphere and mood to communicate this idea of desire, which cannot be visualised. Ultimately, it still comes down to visuals for me. How does one construct a work such that it hints at what is beyond the image?

On the other hand, Eiki Mori’s work documents life with his partner over a period of one or two years. It’s a very personal take on the idea of relationships — particularly relationships within an Asian context and, I guess, in a homosexual context as well. For me, drawing the link between the movie and the photo book works because of, and I don’t know if it’s fair for me to say this, an Asian sensibility when dealing with notions of intimacy and desire. This, of course, resonates with me on a very personal level too. It’s no longer about what is said, but what is not said. That relates to the series Until Then. Of course these images are about what’s shown in them. But even more so, they are also about what’s excluded from the frame.

When I first began working on Until Then, I was thinking about how I could present very personal ideas such as desire, love and relationships — things that were not visual — through visual language. I was also thinking about performativity and visibility. Perfomativity in relation to the performance of one’s identity, be it one’s gender identity, or the performance of one’s feelings. I also thought of visibility on two levels. Firstly, there was visibility on a social level. How is queer identity visible through the media, such as through movies and film? Secondly, I thought about visibility through the lens of photography as a visual medium. When one thinks about what it means to be young and queer in Singapore, one often thinks about the drag queens or incredibly sexualised bodies. But from my own personal point of view, it’s often very mundane or ordinary situations that can’t really be articulated in a sexual manner. So I began thinking about how one can begin to talk about sexuality without falling back on these visual tropes or stereotypes.

That’s why I really enjoy Eiki Mori’s work. It came from his point of view, and showed how everyday life was like with his partner. In doing so, these photographs capture a certain sense of casualness. In turn, that casualness lends itself towards our understanding of how accessible these images are. I only found Eiki Mori’s images after finishing up Until Then. When I found it, I found myself wishing that I had made this work. But it obviously comes out of a different context and a different approach.

It’s interesting that you point out the sort of images that people think of when they consider what it’s like to be young and queer in Singapore. Maybe it comes from the fact that social media and visuality is structured, in the sense that it lends itself towards personalities that are louder and more colourful. Given that propensity, is there a particular visual language you strive towards in your own works to speak of an experience that reflects the ordinary or the everyday?

My approach for this series wasn’t a direct response to the loud and proud images. It’s more of — that’s who I am, really. It’s a reflection of my own person and personality. If anything, it’s probably because I’m more reserved or shy, and that’s why my approach can be read as such. I’m not consciously making a statement against something that’s more loud or brash.

I’m really interested in the visual language of your works because I notice that for your project Beneath the Bodhi & Banyan, the photographs were taken on expired film. Working with expired film gives the images a very distinct aesthetic quality as compared to working with normal film. Every photographic project is as much about the concept as it is about the execution, so how does one feed into the other in the context of projects such as Until Then or Beneath the Bodhi & Banyan?

I collaborated with my friend, Chu Hao Pei, on the project Beneath the Bodhi & Banyan. It was his idea, originally, and we were finding ways in which we could use the process to imbue more meaning into the resulting images. The project was about tree shrines, particularly why these shrines were discarded or left in a particular spot.

We had different ideas in mind, and in the end we decided to use expired film. Firstly, we wanted to experiment with it for fun, but it also allowed us to emphasise the notion of analog media as old or antiquated, and expired film as passing its use by date. Both of these elements were reflective of the tree shrines, as most of them were discarded relics. It paralleled this idea of something as being past its prime. When we collected the developed photographs, we realised that this washed out effect created an eerie or ghostly feel about these photographs. We thought that was really cool, because it was unexpected. It’s similar to how it is like to find these tree shrines. They are never in predictable places — they’re by the road, or in the jungle. Using expired film really added another layer to the photographs, not just throughout the process, but in the final visual presentation as well.

When we exhibited Beneath the Bodhi & Banyan at the Substation’s Concerned Citizens Showcase, we printed the images on different materials such as aluminium and acrylic. By using various materials, we wanted to highlight how varied these tree shrines were. They are all of different sizes, and often belong to different religious as well.

For Until Then, I used a 35mm point and shoot camera. I used a small, compact camera for this project because I wanted it to be casual and informal. Whenever I met my subjects and collaborators, I wanted to put them at ease, and I felt like a smaller camera would have been more effective as compared to a large DSLR camera.

When you take a photograph on film, you can’t turn the camera around to look at the image you’ve just taken. It really forces you to just be in the moment and to spend time with that person, so that’s something I enjoy with using a point and shoot camera as well. I hope that immediacy shows in the work as well.

⁵ Beneath the Bodhi & Banyan, Lee Chang Ming

2018

2018

On that note, what are your thoughts on shooting on film and with a digital camera? There are artists who only shoot with analog film, and relish in the process of developing their own photographs as well. On the other hand, there are artists who work solely with digital images. As someone who works with both film and digital photography, how do you understand the relationship between the two in the context of your own practice?

Another part of it is the romantic side of the medium.

At the heart of it, analog photography is still closely related to the chemicals used and the scientific reactions that give rise to the eventual image.

I read a quote somewhere before that sums this up quite nicely, and it said that to use a medium such as film was akin to alchemy in how the light reacts with silver to immortalise a moment in time. There is this idea that links alchemy to image making, and I think that’s kind of romantic. As compared to snapping a photograph on your iPhone, analog photography is also a transformative process. If I had to take a photograph then wait two weeks for the end result, somehow I end up liking the image more.

We’ve definitely divorced image making from this alchemic process when we take photographs on our iPhone, and I think it also has affected the way in which we consume images. As we look at images through screens now, many of us can forget the sort of process that goes into putting these images together.

Having experimented with different modes of display, be they in physical spaces such as exhibitions, or online, what guides this process of redisplaying the same body of work in different formats? For example, Beneath the Bodhi & Banyan was both a physical exhibition and a photo book.

Photography, for me, is a whole process. Even before taking a photograph, one already has an idea in mind. Based on that, one figures out how to make the image, then thinks about how one would show it — be it online, in a book, or an exhibition space. The eventual response from viewers also feeds into this entire process. Showing the same work in different mediums and contexts is also part of letting go of the work, and observing how people then respond to it.

If I show a body of work within a physical space, I can play around with display methods, and that can be very powerful. However, the exhibition has a lifespan and won’t last forever. On the other hand with a publication, the book can travel to different places around the world. The process behind putting together an exhibition and a book is also very different. With a book, one has to consider how the images are selected and sequenced. In particular, the thing about showing the same body of work in two different formats is that it elicits a very different response from people as well. It fascinates me to know that audiences experience something vastly different when viewing the photographs in the Substation and holding them in their hands as a book. The two formats draw from the same body of work, but the meanings develop between iterations. The exhibition and the publication also reach different audiences. With an exhibition, it would be specific to the exact geographical location in which it was held. But with a publication that is sold online and brought to art book fairs, it can reach an international audience.

Aside from these methods, have you been tempted to play around with other forms of display to get new iterations out of your works?

This was more of a collaboration, and I’d really like to explore such collaborative efforts more. This way, it goes beyond being a one man show by getting more people involved. I think it would be meaningful and fun to make something new out of the same set of images or materials by working with a group of people.

⁶ truth study center, Wolfgang Tillmans

Tate, 2005–ongoing

The sort of participative collaging and splicing of information was something Wolfgang Tillmans explored in his work, truth study centre, at the Tate. The photo book you picked out for this interview is a survey of his practice, but its title draws from this particular work. Could you tell us more about what you enjoy about Tillmans’ work, and how you relate to it?

The breadth of Tillmans’ works is incredibly wide. On the one hand, you have images that are intimate; but he also produces works that look into photography as a medium. Yet somehow, they all come together as a whole.

What I like about Tillmans’ work is that it’s never about a single image. It’s always about his entire body of work — be it within an exhibition space or a book. From what I know of Tillmans, he is very particular about how his exhibitions and photographs are installed. It’s very much about the presentation.

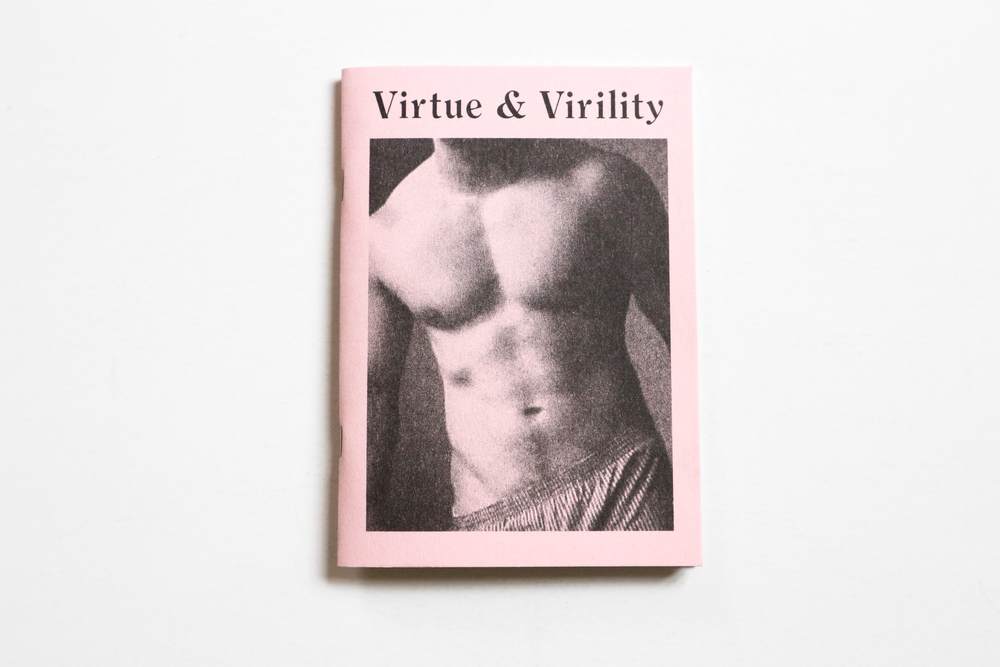

Another project that you’ve worked on recently is the zine, Virtue & Virility. The zine is risograph printed, and brings the world of Tinder into the real world through a tangible product. Risograph inks never really dry down completely, so every time book is handled, some of this ink transfers onto the viewer’s hands. Was it an intentional choice to push the medium towards being a tactile experience as well?

Yes. I had all of these images, and I wanted to do something to it. I couldn’t add anything to this collection of images if I had shown it on another online platform. Given the subject matter of all of these bodies, there was a certain kind of physicality to these images, so printing them out made sense. I thought it would be more interesting to show them in a completely different context.

I was also thinking about the concept of haptic visuality by Laura Marks, which was initially conceived in relation to cinema.

Expanding that towards photographed images, I wanted to see how I could play on ideas of touching with not just your eyes, but your hands.

In a queer context, there is also the added suggestion of getting dirty. Printing these images out into a zine allowed me to add yet another layer of meaning to them. Although I didn’t take these photographs myself, I wanted these images to go beyond being just images I found towards being a new work I created.

⁷ Virtue & Virility, Lee Chang Ming

2018

2018

Many of your works deal with being young and queer in Singapore, and there are a couple of artists who are also exploring this in relation to their own personal experience. Some artists are of the opinion that if viewers see the queerness in their art — great! Others feel as if this aspect of their identity should foreground their entire practice. There isn’t a right or wrong answer to this, obviously, but what do you make of the role of art and photography in light of this wider conversation?

You said something about how should viewers see the queerness in an artwork, then that’s great — I think my artwork falls into that category.

My works are not just about being queer. They’re also about people, and these people are not just queer. They’re people.

Of course, it is a part of one’s identity, but I never want it to be loud to the point that the work ceases to be about anything else. I’m always open to people having their own take on my works — did I answer your question?

Yes, you did. Every artist is composed of various facets, but particularly with artists who identify as queer, it can often be the only lens through which audiences understand their work.

When I’m making the work, I don’t really think about it. But when I show it, everyone always asks me about issues relating to identity. I do think about it in my own personal life, of course, but I don’t really think about it when making these photographs. Especially because I don’t just make portraits. Some of my images are still life or scenery, so why do people only pick up on this identity part? I’m just going for a more emotional take on things.

If a very different photographer had taken the same images you did, it could have been read very differently. I think viewers often subconsciously factor in who the photographer is when reading an image. For example, if a white man took the same photographs you did, it would have been read a very different way.

I guess the question then is: can a white guy take these same images?

This was also something I’ve been thinking about — who gets to represent certain communities? Like, who has the right to speak, particularly, on behalf of marginalised communities?

For me, this is my own personal position and I do have access to certain perspectives. I’m not forcing my way into it, but I still see value in talking about this experience.

It’s something that I don’t see around — at least not in my immediate surroundings — so I do think there is value in telling this story.

I wanted to talk about your work with Nope Fun as well. You’ve been maintaining this platform for awhile now, and I wondered if you could tell me more about what was the impetus for starting the website?

When I started it, I didn’t really think too much into it. I was looking at all of these other blogs and websites, and I just thought I could do it too. It’s also a great excuse to talk to other artists and photographers whom I’ve been inspired by. That was eight years ago, and I just started getting in touch with all of these people I had been inspired them. Surprisingly, most of them were okay with it. I would ask them all of these frivolous questions, which are quite funny. With time, people started getting interested and I started receiving submissions on the website. I would just pick out those I like, and the features are always kept really simple with less than ten questions.

I also like choosing the images and sequencing them. I didn’t really think about all of this back then, though. It was just something I liked doing, and was doing intuitively. So when I first started Nope Fun, it wasn’t about making a huge statement or anything. It was just for fun — hence its name.

Moving forward, I’m interested in doing more printed matter, be they zines or printed books. I’ve always been interested in that, so it makes sense.

There’s a growing community of art book makers here in Singapore, but I understand you’ve also attended art book fairs internationally. How different are the art book communities locally and internationally, and have interactions at these art book fairs helped shape your approaches towards art book making?

I started by putting my works out on the internet, so I don’t think I’ve ever felt a marked difference between the local and the international. Because of that starting point, I’ve never been particularly conscious of a local audience. For example, the readers of Nope Fun are based all around the world. The website is in English, so naturally the website sees a higher percentage of visitors from English-speaking countries. But the website is also visual, so aside from the interviews, visitors from all around the world can still appreciate these images. Although I don’t read Japanese, I follow some Japanese blogs as well because they post great visual material.

I’ve never really seen a line, where I’m thinking of how to create solely for a Singaporean audience. I’ve probably been more conscious of this in recent years, especially in relation to exhibiting in Singapore. But when making my publications, for example, I’ve never really had a specific audience in mind. I’m not sure if this is for the better or for the worse. The work is printed in Singapore by a Singaporean artist, but the process of making the work is not specific to any country or locality.

But why do people even care about a Singaporean voice? I mean, I understand — it’s more of a rhetorical question.

It’s always the inescapable cycle in the sense that an artist is obviously a product of where he or she is from or based out of, yet there are many things that connect us that transcend these geo-political boundaries. It’s tricky because one doesn’t want to fall into the trap of reducing artists into a monolith. Yet in teasing out local sensitivities, we could sometimes lose the real essence of what the work is about.

I guess it’s also about the nature of the work, and the subject matter at hand. I think my work is a little more ambiguous in that it allows viewers to speak about things that are not country-specific. Ambiguity is pretty important for my works. Ideally, I’d like to work on more collaborative projects where if I work with someone from Hong Kong, for example, they’d be able to bring a completely different point of view to the table.