Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Old-Growth

Issue: On Old-Growth

Lêna Bùi lives and works in Saigon, Vietnam. Her works are sometimes amusing anecdotes and other times in-depth articulations of the impact of rapid development on people’s relationship with nature. She reflects on ways that intangible aspects of life, such as faith, death and dreams influence behaviour and perception. She often relies on drawing and video to articulate her thoughts.

Filed under: drawing, film, installations, painting, photography, sculpture

¹ Dear Animal, Maha Maamoun

2016

You’ve picked out five works of art that, at one point or another, have had a profound impact on you and/or the way you see your practice. Could you tell us a little more about how you put this selection of artworks together?

Before this interview, I looked at the list again. I realised that these are all works that I saw early on in my career, so I think that there was an element of being impressionable, and of being open to new things. What they help with is that they create models of structures that can combine various things and hold together different kinds of information while simultaneously remaining very loose and fluid — similar to how memory works. It’s not completely linear. It jumps back and forth, and sometimes expands sideways.I don't necessarily bring the content from these works into my own works, but they provide a framework for how all these different tiny bits of information and misinformation that I accumulate and create can be managed, and how I can form networks or connections between them.

² The Missing Voice (Case Study B) (Part One), Janet Cardiff 1999

On the other hand, you also mention drawing upon the quotidian and your surroundings as well. Are there particular elements of everyday life that you find yourself compelled by, or certain aspects that you’re drawn to?

The nice thing about having gone abroad and having lived in different places is that the things that someone who stays in a certain place for a long period of time might take for granted will stand out for me. For example, even the colour of the altars here fascinate me.

I care a lot about the environment I live in. My works are sometimes about food, or about small plants that you don't recognize, or about the changes around us that are happening so quickly. When I go into town, I sometimes notice that a building has changed completely. Yet I can’t really remember what existed in its place before. Lapses in memory, everyday things that stand out, and the moods they create — these are all things that become content for my work.

I care a lot about the environment I live in. My works are sometimes about food, or about small plants that you don't recognize, or about the changes around us that are happening so quickly.

³ Sans Soleil, directed by Chris Marker

1983

⁴ As I Was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, directed by Jonas Mekas

2000

You’ve touched on ideas of memory construction, fragmentation, and looseness in your earlier responses and a couple of the works you’ve selected, such as Sans Soleil and As I was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpse of Beauty, reflect this. What would you say the importance of storytelling and narration is to how you encounter or perceive, and in turn, how this perception feeds into your own creative practice?

My family members were teachers and engineers. None of them worked in the arts, so I grew up with books. When I was a child, my family didn't have a television set, so my mother used to read to me every night. That's just how I accessed different worlds, so for me, narration and storytelling is very natural — and maybe it is for all of us. When we tell or recount incidents in our lives, that's basically storytelling. Reality is often very chaotic, and stories help with bringing different pieces together. It makes everything a little bit more manageable, and I like that. What draws me to the arts is that I can make sense, or not make sense, of things. You could try gathering different things in order to create some temporary form for them, and the form could be ongoing, complete, or just the first step to something bigger.

I think that painting is a form of storytelling as well. You're using a visual language of colors, shapes, and forms. It can sometimes be very figurative, but other times be very abstract as well.

What draws me to the arts is that I can make sense, or not make sense, of things. You could try gathering different things in order to create some temporary form for them, and the form could be ongoing, complete, or just the first step to something bigger.

⁵ Making rubbings of tree stumps on Ton Duc Thang street, Lêna Bùi

2018

Photo by Chuong Pham

⁶ Assembling the rubbings in the studio, Lêna Bùi

2019

2018

Photo by Chuong Pham

⁶ Assembling the rubbings in the studio, Lêna Bùi

2019

⁷ Rashōmon and Seventeen Other Stories, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

Like the stories we soothe or calm ourselves with, right?

The more I look into it, the more I realise that stories are actually everything. The national narratives that we were fed, or the things I learnt in school — these are all stories. Of course some might be rooted in reality, and others might seem a little unhinged. Sometimes you hear about an incident, but might later be confronted with a completely narrative. These are two different narratives about the same event, and they don't necessarily agree. I think that all of these things are really important: how you see yourself, how you see other people, how you make sense of the world, the different stories that we believe in, we tell ourselves, we tell others, we hear from different sources, the personal stories, the national stories, and even the global stories. Having worked as an artist for a while now, I’ve also gotten a better sense as to how these stories can be broken down. When I was younger, I would have just received them passively and naively. But now, I listen — really listen — to how the story is packaged, the contents of the story, the motives of the storyteller, and more. This is probably what happens as you grow older. You’re no longer just a passive listener.

I think that all of these things are really important: how you see yourself, how you see other people, how you make sense of the world, the different stories that we believe in, we tell ourselves, we tell others, we hear from different sources, the personal stories, the national stories, and even the global stories.

Another story that many of us who live in rapidly developing cities grapple with is that of urbanisation. A recent project of yours is rooted in the collateral damage that emerges from this development, and in particular, the felling of indigenous trees in Ho Chi Minh City. Could you tell us a little more about the project, and how it came to be?

One of the oldest roads in Saigon is right in the centre of the city, and I grew up here. It’s probably the most shaded road, with rows of giant trees — more than two hundred trees — along just one road. Three years ago, they decided to chop down the older trees (in total, 143 trees were felled). The younger trees were uprooted and removed. They did it so quickly that a lot of people didn't even realise what was going on. Going past this street and seeing this happening, I was completely shocked. That was when I started looking into it. A lot of these trees were planted during the French colonial period, so most of these trees were more than 160 years old. They're very old, big and beautiful. I also realised that these trees are not native to Southeast Asia. This tree, called a khaya senegalensis, is native to West Africa. It’s actually really interesting, because you can trace their histories to the time they were brought to Vietnam and germinated at the Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens, which was also set up by the French. When we think of the colonial era, we always think of the French and France. We don't immediately think of West Africa, or of the other countries that were colonised by the French Empire, and how we are connected to them. I really wanted to work with this because the tree was a sort of meeting point. I just thought it was like a living witness, an intersection I could place all these different materials that I was interested in.

I was also thinking of a very common belief that we have here where we believe that spirits reside in trees, especially hungry ghosts with no place to go. That’s why you’ll always see altars placed underneath certain trees everywhere in Vietnam. It’s a form of belief that’s a mixture of Taoism, Buddhism and local traditions, so it's not organised. The spirits are alive because people believe in them. This allows me to bring in another voice and another perspective.

The trees themselves have their own way of observation and thinking that also allows me to imagine something beyond the human. I don't mean this anthropomorphically, but rather to try and "phytomorphize" myself ー to think like a plant.

The khaya senegalensis is also commonly found in Singapore, just that it’s called the Senegal mahogany there. It raises so many questions for me, such as: who decided to plant these trees? Who decided to plant this particular tree species? How did the seeds travel? Were there seed exchanges occurring between countries? This project gives me a chance to look into all of this.

⁸ Chainsaw marks 2, Lêna Bùi

2019

⁹ Chainsaw marks 3, Lêna Bùi

2019

2019

⁹ Chainsaw marks 3, Lêna Bùi

2019

There is a very strong community spirit, as you say, that surrounds some of these trees, even as they are located along bustling thoroughfares. One example of this can be seen with tree shrines, which you touched on briefly. How do tradition, community, urbanity, and everyday life collide or intersect within the context of this particular area before and after the trees were felled?

The pavements along this road are actually very large, so there's vibrant life on the side of the road. There are barber shops, for example, who have been operating at the same spot for thirty years. When the trees were felled, I did physical rubbings of the tree stumps. I was on the street everyday for one month, and lots of people would stop and chat. There’s a social dimension to this, and it goes beyond the mythical aspect. Once they chopped the trees down, it became the ugliest road in Saigon. The pavements are so hot now — people want to get out of there as soon as possible.

The way that I'm trying to set this up is by thinking about how spirits move between trees, and that there are all these homeless spirits now. I’m not fixated on this one particular street, but I think of it as an opening lead towards things that I want to say, or other interesting connections.

What would you say is the connection between this project and previous exhibitions or works you’ve done, for example, previous works you exhibited at your solo showcase in 2016 titled Flat Sunlight? How do you make sense of the place of this project vis-à-vis previous projects you’ve done?

I think that this is a standalone project, but my interest remains the same. With previous projects, such as the one at The Factory, I looked at our relationship with the environment through food and through the different weeds that grow in the city. According to traditional medical texts, some of these weeds have healing properties. I was looking into these kinds of lost knowledge — information that perhaps my grandma would have known quite well. What herbs help to stop bleeding? Which herbs should you drink if you're having a cold? When I look at these plants, all I see are weeds. It was interesting to see how our knowledge influences what we see, so that work was about these small, grass-like plants that we could still find in the city.

After that work, I did a piece that focused on urban development. This was commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation. The piece was a comparison between Saigon and Sharjah, which are both cities that have developed by the side of large water bodies, and have very big ports. In Saigon, and probably Asia in general, development tends to happen very quickly. We tear down old buildings very quickly, and with very little consideration. One example was the demolition of the Ba Son Shipyard in Saigon. It was the oldest shipyard in south Vietnam, and it was there even before the French came to Vietnam. It was built by the Nguyễn Dynasty. Four years ago, it was demolished to make way for luxury highrise apartments. With historical landmarks and places, once you've destroyed them, they're gone. You can't rebuild them. On the other hand, Sharjah wanted to preserve parts of their city’s Old Quarter by turning them into museums and gallery spaces. However in order to do so, they kicked everyone who lived there out, and relocated them to the outskirts of the city. Although the area is now preserved as a museum, it's in a way dead, void of the lively energy of the people who actually made a home there. I found these two opposing directions quite interesting. There’s always this tension between preservation and development. Too much preservation does something weird to a place, and too much development is just destruction. It’s a question I’ve always wondered about. It is, like most things in life, a complex issue. That’s why it’s difficult to arrive at a place that’s balanced. Things are always in flux.

¹⁰ Innocent grasses, Lêna Bùi

2016

2016

In listening to you express your thoughts, I’m struck by this deeply relational, or if I may, ecological perspective that you carry with you. Why has it been so important for you to center this notion of making connections and sitting within networks?

I think that connections can be built between anything. If you place two unrelated objects next to one another, and leave them there for a while, connections will somehow form between them — connections that are beyond you. I saw a Brazilian film recently about the filmmaker Eduardo Coutinho. He touched on ideas about how the other is actually part of you, and you a part of them. You don't exist independently. Whatever you're facing, it holds a part of you, and you hold a part of them. What we know affects what we see. Even if two people look at the exact same thing, they can each have very different experiences. It all depends on their individual memories and experiences.

I also moved around a lot as a kid, and it created this dichotomy where I always felt like an outsider. It allows me to look at things from a distance, but there's also a desire to belong. It also helps me with being very flexible. I can go to a new place, adapt quite quickly and somewhat fit in. Making work is a way to make connections with a place or people, maybe it's a form of survival for me.

Making work is a way to make connections with a place or people, maybe it's a form of survival for me.

Let’s spend some time talking about how you approach the process of conducting research and fieldwork as well. In working on a project, you’re constantly collecting lots of material in the form of things such as historical fragments, photographs, or making sketches. How do you approach listening to these materials, and following the grain of what they might have to say to you?

It's completely chaos at the beginning. It's terrifying. I often feel like I'm procrastinating and I’m not doing anything. I could look at one thing and later end up somewhere completely different — sort of how it is like going down a rabbit hole by spending time on Wikipedia. Even now, I've never been successful in actually incorporating these different fragments into an articulation that's powerful. That's still my aspiration.

It helps to have a deadline. It helps to know that within this timeframe, this amount of work is realistic, and it allows me to set realistic goals. I actually think that limitation is incredibly important, because too much freedom can be dangerous. When there are no rules, you’d just find yourself inundated. Having a budget constraint, a time constraint, or even a constraint with skill sets can be helpful.

It also helps to tell myself that if something interests me enough, I will continue working on it, so it's okay to stop there for now. The things that I’m interested in tend to loop. They might appear in one form today, then it sits somewhere for a little bit before being reincarnated into another form later. As I’ve developed my practice, I’ve learnt to trust my intuition more, to trust expressions beyond words.

I don't know if there are other artists who have this fear, but I have this fear of my work becoming illustrative. That would mean that it’s locked up and can only be read in a limited way. Now that I’ve worked for a while, I have a better sense which threads are worth pursuing, or which images are strong. I go with the flow without rationalising my pick all the time, and things somehow come together — from panic.

¹¹ Home (good infinity, bad infinity), Lêna Bùi

2018, Installation view at the Sharjah Art Foundation

¹² Home (good infinity, bad infinity), Lêna Bùi

2018, Installation view at the Sharjah Art Foundation

2018, Installation view at the Sharjah Art Foundation

¹² Home (good infinity, bad infinity), Lêna Bùi

2018, Installation view at the Sharjah Art Foundation

Could you expand on what you mean when you talk about works that are illustrative? What comes to mind?

Say if I cared about the felling of trees, but I just made some drawings of fallen trees, that would be quite a shame. With the works that I admire, they tend to seem deceptively simple, yet they make you think and question, often without giving you neat answers. You’re left with a question, an image, or a feeling. I would love to be able to accomplish that, so that’s my hope.

I’ve also realised that most of the works I love are, in some sense, spiritual. They are honest, and they are personal. I don't mean personal as in deriving from personal experience, but rather personal as in stemming from a deep-seated personal quest ー a need to touch the sublime and the enigma that is life. Their works make me feel intensely alive. I hope before I die I can make one work that can transmit that feeling.

When we speak of indigenous botanical knowledge, folklore, and traditional practices in relation to urban development and living in cities, often an inextricable sense of loss or the threat of loss is brought up. These sentiments can oftentimes seep into a work and soon become rather overwhelming. How do you navigate through them?

That’s definitely a trap that I don't want to fall into because I am quite a nostalgic person. However I do think that change can bring joy to a lot of people. Sometimes people resist change just because it's different, and not necessarily because it's bad. It’s important to be aware of that, and to try to allow for that other perspective to enter the work as well so that it is not just a lamentation for the past. I've always really loved music where traditional elements are mixed into techno or electronic tracks. I love it when you give something old a new life. It is definitely a challenge, and I don’t have an answer or a solution for it. It’s just something I need to be aware of.

I’ve also been working on a side project with a friend that looks at how people who live in new highrise apartments form communities. How do they socialise, engage in activities, or form bonds? I’m very curious about how people make sense of new environments, or how they customise modular living spaces. Humans have this incredible ability to adapt and to work with what we have, and we are social by nature. Even if most of us no longer live in villages, I find these new modes of connection fascinating, so that’s something I’ll be looking at moving forward.

Sometimes people resist change just because it's different, and not necessarily because it's bad. It’s important to be aware of that, and to try to allow for that other perspective to enter the work as well so that it is not just a lamentation for the past.

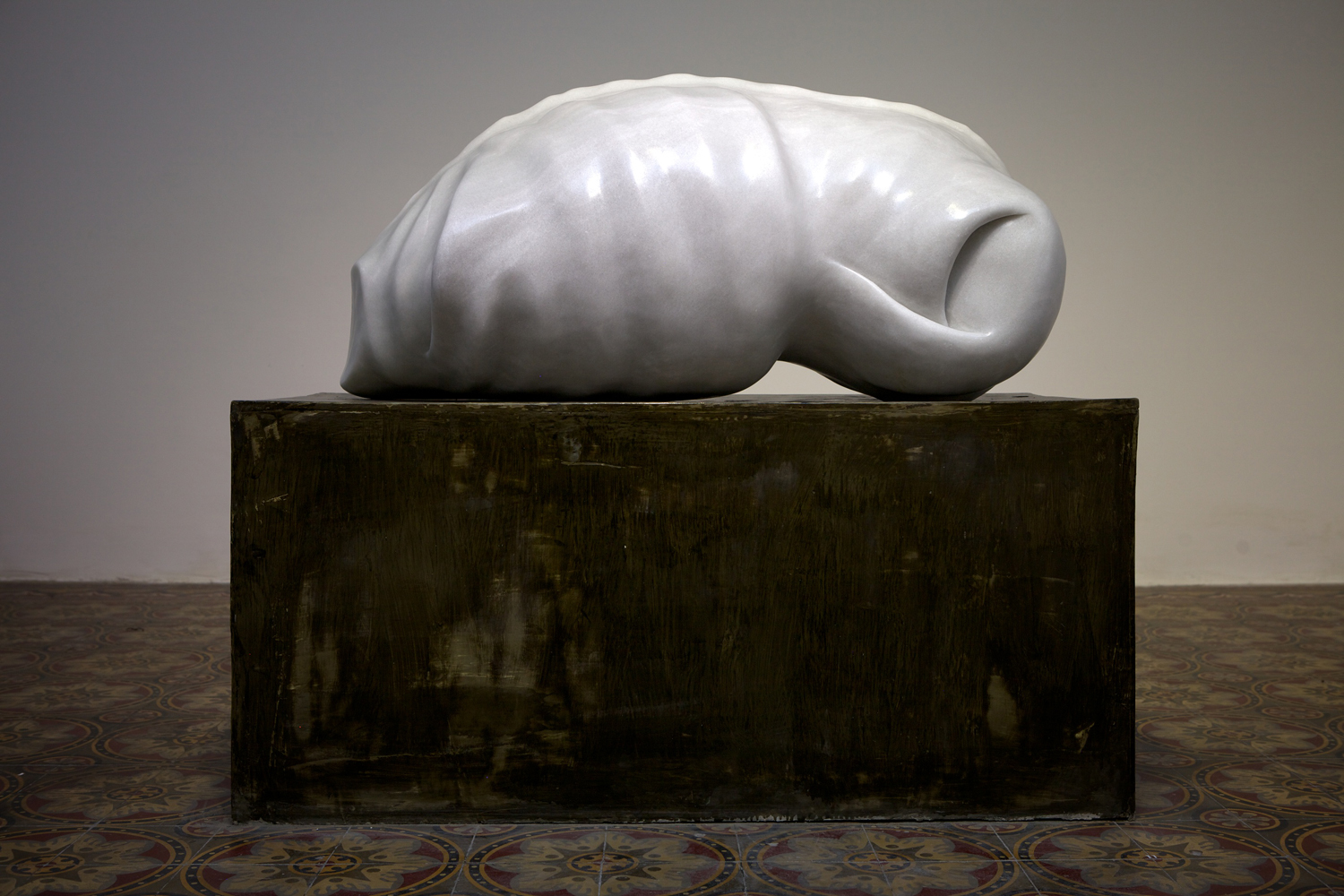

¹³ Life from death, from life I, Lêna Bùi

2012

¹⁴ Life from death, from life I, Lêna Bùi

2012

2012

¹⁴ Life from death, from life I, Lêna Bùi

2012