Liana Yang is rarely motivated by direct beauty, but drawn to the aesthetics of social interactions and oddities we encounter in our daily experiences. This includes the enigmatic and unseen aspects of relationships, as well as explorations of memory and associations in contemporary culture. Her research has revolved heavily around observations in photography and contemporary cultures, such as social apps and online media. Her works have been showcased at Chobi Mela International Festival of Photography, Noorderlicht International Photofestival, Arles Photography Open Salon, Singapore Art Museum@8Q and Warsaw Photo Days. Her three self-published photobooks were selected and showcased internationally, such as the Photobook Shows in Brighton, Helsinki, Malmo, Tokyo, and in her hometown, Singapore.

Human relationships are sticky, tenuous, complex, sensual, pivotal, and altogether difficult to describe in words. As an artist whose practice explores the connections we share with one another, Liana Yang embraces all of these facets. As part of her work, she collects materials and images from online dating platforms, popular romance novels, and pornography. In spite of the eroticism embedded within such material, Liana’s works are transgressive in terms of their fierce intimacy — befitting of the full-bodied experience portrayed. Throughout our conversation, Liana steers clear of identifying with definitive labels — a resistance that is significant in relation to the ideas she wrestles with. For our conversation, Liana picked out objects such as her cat, chocolate, dark spirits, music, online dating apps and her cameras.

Human relationships are sticky, tenuous, complex, sensual, pivotal, and altogether difficult to describe in words. As an artist whose practice explores the connections we share with one another, Liana Yang embraces all of these facets. As part of her work, she collects materials and images from online dating platforms, popular romance novels, and pornography. In spite of the eroticism embedded within such material, Liana’s works are transgressive in terms of their fierce intimacy — befitting of the full-bodied experience portrayed. Throughout our conversation, Liana steers clear of identifying with definitive labels — a resistance that is significant in relation to the ideas she wrestles with. For our conversation, Liana picked out objects such as her cat, chocolate, dark spirits, music, online dating apps and her cameras.

Your selection of things is incredibly sensorial — you touch on ideas of looking, of listening, of touch, and even of taste. As someone who works in image making, tell us about how important facilitating a corporeal, embodied or even carnal experience through image is to you.

My practice began with photography, so much of the challenge was actually to convey more through a very static form of presentation. We normally think of photography as something that is two-dimensional and hung on the wall. There are, of course, people who will argue against this. I’m also not saying that there’s anything wrong with presenting images as two-dimensional flat surfaces. However, because I’m interested in themes such as love, relationships, desire and intimacy; being able to facilitate a sensorial experience through print is incredibly important. It isn’t an afterthought. Even before I make a work, I'm constantly thinking about these issues. A photograph can have arresting qualities and contain captivating elements, but I think I prize simplicity within my photographs as well. Theoretically speaking, we know that a photograph needs to be supported text in order for it to be fully comprehensible to the viewer. Without this accompanying text, the photograph is left to function in a purely semiotic way. For me, this simplicity also creates a certain tension. We are left to negotiate the meaning of these photographs on our own terms. Yet at the same time, there isn’t much to distract the viewer in encountering the photograph. The viewer is hence encouraged to pay closer attention. This invitation becomes a more intimate experience, and I would compare it to opening a door for viewers to step in and have a look around.

In some of my exhibitions, I incorporate other elements to create a mixed media experience that heightens the viewers’ senses. This could be in the form of sound, video, found objects, or even scent. By including these sensorial elements, I hope to create a more immersive engagement for the audience. When it comes to the two-dimensional photograph itself, I’m careful to consider things such as dimensions and the medium that the image is being printed on. These are all crucial choices I make. I also think it’s important for me to get a good sense of the exhibition space. What does it look like when viewers step into the exhibition space? I take a hands-on approach to planning my shows and working with the curator, if there is one. I’m usually making the decisions with regard to where the works should be placed, how they should be hung, and even the colour of the exhibition walls. This is important even in the context of group shows. I think it is essential for me to understand whose works are going to be placed beside mine, and how viewing the works together can create a nice synergy.

Earlier on, you mentioned striving towards this idea of simplicity when making a photograph. Simplicity is something that can mean very different things, depending on who you ask. It could refer to a reduction of visual clutter within an image, but could also point towards essentialising a single idea within an image. When you speak of a simple photograph, what does that look like for you?

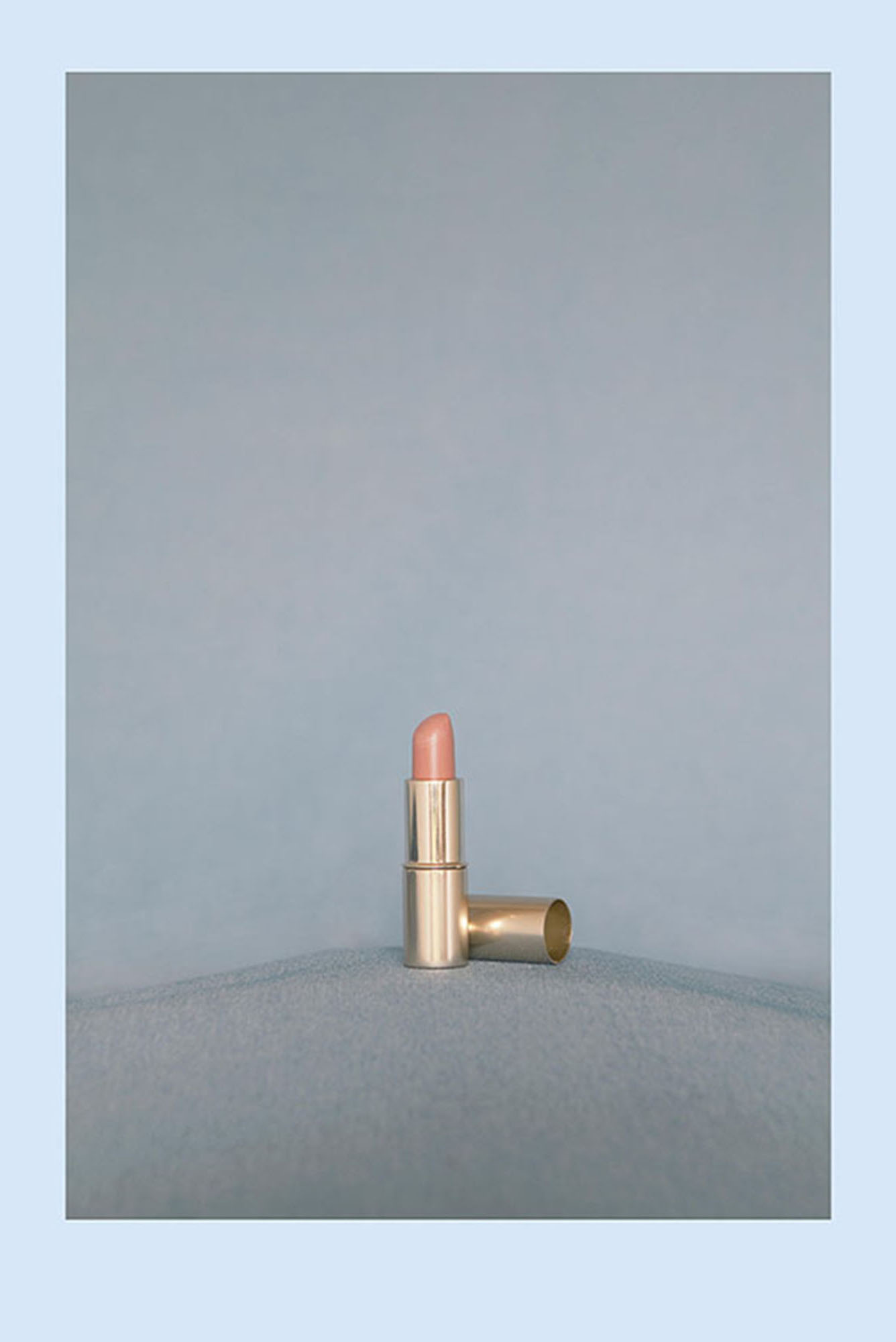

It really depends the work that I’m making and what I'm trying to convey. For projects such as Year 0 and What My Pussy Loves, both works depict very basic objects. There definitely is this fascination with the banal. Having said that, it depends. For some of my recent works, there is an undoubted cinematic feel to them. There is this sense of catching something and looking at it mid-action. It always comes back to what the work is about and the narrative I’m trying to get across. I get bored very easily, so it’s hard for me to say for sure. My style or how I make images could change tomorrow.

Year 0, Liana Yang

2015

2015

One of the things you picked out for our conversation is online dating apps. There are so many dating apps out there right now, and I know you have used these apps as a resource for your work as well. Tell us about how you usually approach and collect information off these platforms, and if you think of this process as a voyeuristic one.

I started using online dating apps because of a failed relationship. I had a lot of unanswered questions at that point in my life. I wanted to figure out if there was some kind of modus operandi in finding love. It started off as a naive exercise, and branched out into four years of observation.

When you put yourself out on these online dating apps, the goal is to get as many likes as possible. This is what we call the swipe right culture. This is where the attention economy comes into play. I started using these apps in 2013, and I was quite self-conscious at the time. My profile picture was a rather obscure looking photograph of my cat and me. The photograph didn’t garner much attention, and it was probably because it looked as if I was hiding behind something. These are subconscious processes that determine how we read or interpret these online profiles, and this is mostly done through assessing someone’s written bio or profile picture. Based on the information provided, we might get a sense of an individual’s emotional, social, educational, or even financial status. In order to get more people to swipe right on my profile, I soon realised that I had to change my profile picture and curate my bio in order to make myself appear more appealing. Once these things were put into place, I was able to get access to more people through these apps. I was able to start having more conversations and getting to know more people.

When I hit it off with someone on these online dating apps, the next step is usually to take things offline. Just to make sure I’m not chatting with a bot. I’ll pick crowded, public and safe places for this meeting, and go in with a set list of questions that I’d like to ask. These questions mainly revolve around the person’s reasons or motivations for using these online dating apps. Of course, not all the meetings go as planned. Not everyone you meet is fully honest about their intentions as well. It takes time to put someone at ease, and it takes time for people open up. Whenever I meet someone, I will disclose that I’m approaching this endeavour as an artist and that my work explores love and relationships. For most of the people I meet, that doesn’t faze them. On the other hand, I’ve also made some casual friends through these dating apps and they share their experiences of using these apps with me as well. This grants me an intimate insight into how modern dating works.

Through these online dating apps, I’ve met a couple of people who have been less than forthcoming about their true intentions as well. I’ve met people who are married, attached, in a strained relationship, or even in the midst of a divorce — but they pose as single individuals. It's a free world, and I'm not here to judge. However, I think it raises interesting questions about the moral layers involved in a relationship, the importance of honesty, and the meaning of human connectivity.

There is no denying that this process is voyeuristic. Some might even consider it as exploitative. This relates to the medium of photography itself. The camera creates images and visual documents. By looking at these images, we involve ourselves as active participants in a voyeuristic loop.

As an artist, the question for me is — how should these images be presented and consumed?

A couple of works have come out of these interactions, but one that comes to mind is Year 0. The work follows an illicit love affair to question to paradoxes of love and the social entanglements involved in a relationship. In the series, there is an image that is made to look like it was taken from the perspective of a private investigator. Other images resemble blurry, dream-like sequences — meant to replicate that fevered, heady state that couples find themselves experiencing in these clandestine affairs. Interspersed with these images were found objects such as a wedding ring, text messages, and still life photographs that run through the possible outcomes of this affair. I’m still interested in how a relationship that begins hopefully can later crumble apart. Is there a logical system, a series of steps that need to be taken, or a set of tasks that need to be fulfilled in order for a relationship to be steered towards a certain path — or does it really come down to fate and serendipity?

There is definitely almost a checklist of things that people should tick off if they’d like to get more matches on these online dating apps. Profile pictures that feature pets, babies or travels are often popular, and users lean into these rather harmless stereotypes because they work. Having said that, there are less benign stereotypes that can be embedded into these platforms as well. This can take the form of problematic, misogynistic or even exploitative behaviour. Whilst collecting material for your work, have you seen such insidious behaviour creeping in? If so, how do you navigate encountering or using these situations?

When it comes to stereotypes, you do see particular patterns peeking through. Having said that, the nuances are always different. Everyone works differently and everyone has a different agenda. I work with familiar objects and found images in order to build connections with the audience. Objects and images possess these very sticky attachments, and sometimes referencing them can touch on certain sentimentalities. Sentimentality can be tricky. When it lingers for too long, it can transform into fantasy. When it becomes fantasy, it then becomes non-loving.

Personally, I think of it as cultivating a loving relationship with my audiences.

That way, it makes the encounter with my work more worthwhile or satisfying. Intention-wise, my work tends to draw from the personal. I think this is very important in art making. Artists should not work like factories — churning out works just for the sake of it.

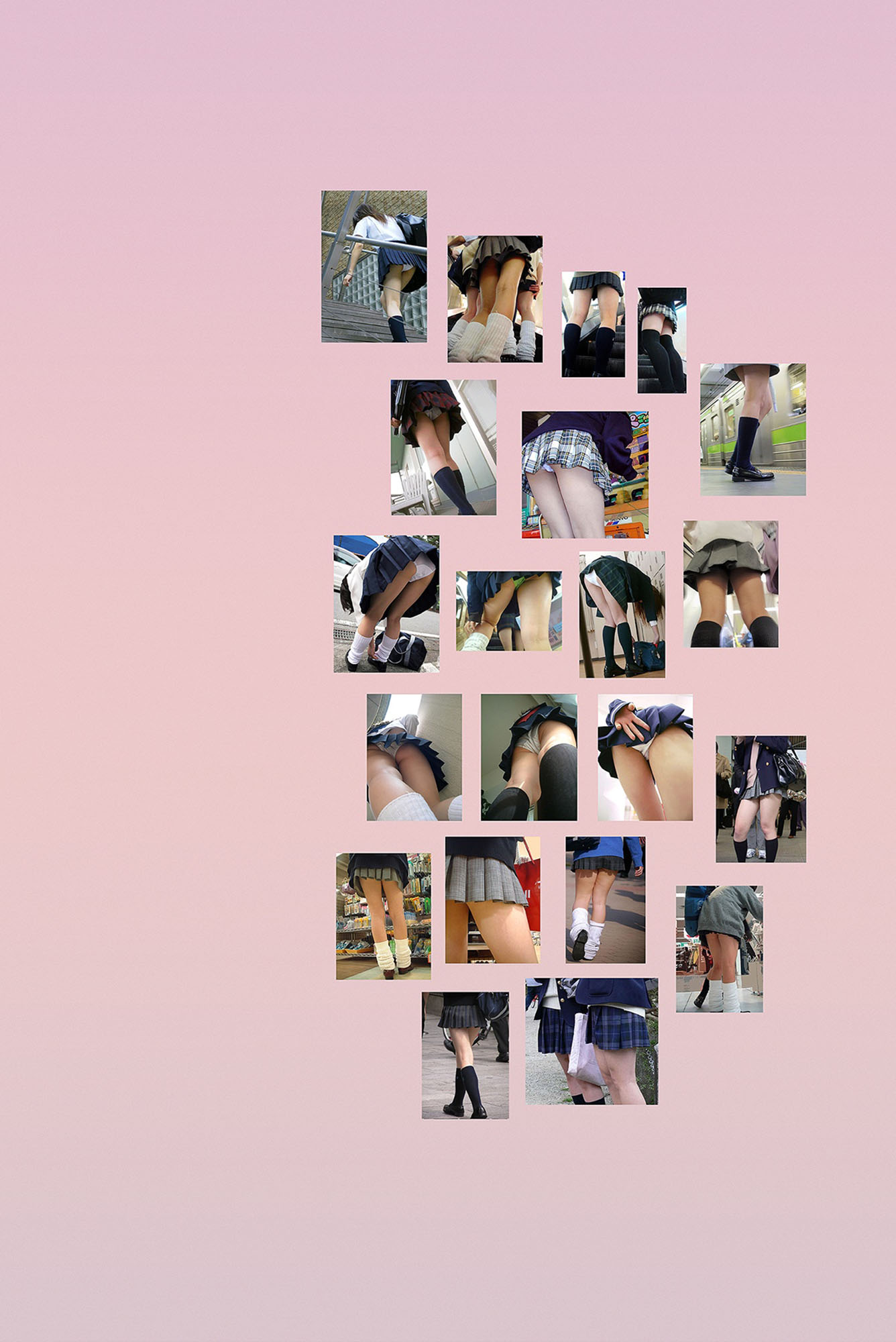

The Innocence Project, Liana Yang

2011

2011

Speaking of the personal, could you tell us about how your relationship with or interest in topics such as love, relationships and sexuality — particularly female sexuality — began? How has this relationship evolved or changed over time?

Early on in my practice, I started out doing street and documentary photography. I got bored of it after a while, but I wasn’t ready to renounce it just as yet. I was still drawn to the enigmatic quality of photography. The pressing question, for me, was how we use photography, how we read images, and how we consume images.

I come from a rather conservative Christian family, but I was always curious about sexuality and unconventional lifestyles. This comes back to my fascination with the human condition. This, of course, led me to pornography. Coincidentally whilst watching the movie Saving Private Ryan, I noticed that the expressions of men in pain were very similar to those you see with porn actors. That was, perhaps, a basic inquiry into the ambiguity of human expression and emotions. You could say that this was a very disturbing epiphany because of how the spaces of pain and pleasure are often seen as polar opposites. In a famous speech about the erotic and female sexuality, Audre Lorde describes the importance of harnessing the power of the erotic. In order to do so, we must first recognise or identify it. With the work The Epiphany of States, this was what I wanted to question. When we cannot even distinguish pain from pleasure clearly, what is the erotic? It was also very important that the subjects of this project were men. I wanted to question these hegemonic stereotypes of men being stronger archetypes — both emotionally and physically. I re-photographed these porn actors in questionable states of pleasure and pain, and digitalised the images for consistency.

Whilst looking for images of these porn actors, I kept coming across images of young women in school uniforms. It’s such a cliché, even within the world of porn. Around the time I was looking into these images, there were news reports of influential and important men getting embroiled in scandals for soliciting sex with underage girls. This was incredibly appalling, but the way in which these stories were reported were in the style of a tabloid newspaper. There was a level of raunchiness and superficiality embedded into the way we approached these stories. I started becoming very interested in the symbolism around the schoolgirl fetish. This led me to begin work on The Innocence Project. With the work, I decided to reposition the schoolgirl as a figure with agency and someone who knows what she wants. Many of the images I used in The Innocence Project came from fetish porn and images of young girls indulging in Lolita culture. Usually, a fetish is something that is rooted in forbidden pleasure, vulgar or socially unacceptable circumstances. With The Innocence Project, what I tried to do was to blur the lines between the male fetish and female sexuality. Coming back to Audre Lorde’s work, she wrote that a woman, or anyone for that matter, who understands their sexuality demands more for themselves. This is especially so when we consider their life pursuits, and this means that they are no longer submissive or innocent.

Today, we still see certain corners of pop culture embrace this idea of the empowered woman as someone who is dangerous or even sinister. Because of these stereotypes, some of us still feel oppressed because not all of us can fully express who we are and what we really want.

With that, I want to stress that I'm not a feminist and I do not make feminist art.

Although we’ve come a long way in our understanding, I think that there’s still much further to go in recognising female sexuality.

The Epiphany of States, Liana Yang

2012

2012

Something that comes to mind when we think of images that deal with the human body, sex or the feminine is the female nude. Throughout your practice, how have you negotiated the long, sticky history of the female nude and where are you at in terms of grappling with that? Is the female nude something to be redefined, reorganised, reinvented, or is it something that we just need to move beyond?

It’s not that I’m ashamed of my body, but I’ve always wondered why a female artist has to do nudes in order to get recognition.

Is that the only way? Why do we have to subject ourselves to the scrutiny of the male gaze, once again, under the guise of female empowerment?

I don’t deny that my works touch on provocative themes. When you explore love and relationships, sex is unavoidable. I wanted to see how I could touch on these provocative topics, yet subvert what people might expect to see in these images by not showing my skin. My work has always tethered between truth and fiction, and to date I’ve only showed some of my skin in one work. That work is Year 0. I only did that because it was pivotal to forwarding the narrative.

I don’t think I have the right to say if the female nude should be circumvented in any way. Neither am I saying that nudity is wrong. It all comes back, again, to the personal. The point here is that the human body, regardless of gender or sexuality, should not be objectified in ways that are undesirable. I’ve seen recent nude works by female and transgender artists that are absolutely brilliant and they were, frankly speaking, necessary. It all boils back down to intention, voice, and urgency. Does one have something urgent or important to say?

These days, I find myself questioning the male gaze. This includes works by cishet male photographers, and these were photographers I used to idolise when I first started out. Art historically speaking, the male gaze has always come from a standpoint of privilege. Standards of beauty are cultivated by this gaze. Having said that, I don’t want to be mistaken as a feminist artist who makes feminist works. I grew up with strong female role models, and have always been surrounded by strong female peers and co-workers. Given that background, I dare not say that I have felt truly oppressed. Even if these things happened, I knew how to move past them and brush them off. Mostly, I just think of these situations as unfortunate. I don’t feel comfortable with these labels. These labels become a quick way for people to simply pigeonhole me, or my practice, into basic categories. It makes for a one-dimensional understanding of my practice.

untitled (Seas), Liana Yang

2011

2011

On that note with regard to the gaze, tell us about the cameras you use, and how you work with each of them — particularly given how each of them have their own qualities.

What I love about each of my cameras is that they produce varying outputs and qualities, and sometimes the results can be very surprising.

Ironically, this is to say that I like this lack of control. I’m now familiar enough with my cameras to know which one to use in order to create a certain mood or image quality. To a certain extent, however, there still is an element of unpredictability within the process. It’s kind of like a relationship. There's always that degree of anticipation and irregularity, and that’s what makes the relationship somewhat exciting.

In one of my recent works, I enhanced this aspect of unpredictability by using expired films. The work is titled There was something to believe in, and it was made in a hotel room in Hong Kong. I shot entirely on expired 35 mm film using my grandfather's old rangefinder. Whilst making the work, I also shot with my mobile phone camera and on Polaroid film. It wasn’t because I needed backup images, but rather I wanted to compare the varying qualities of photographs made with the different equipment. When I was able to compare the three sets of images, it was interesting to see the nuances across all of them. The expired film bore the most jarring difference, and it featured a lot of obscurity especially due to the compromised nature of the film. Through this experiment, I wanted to visualise how physical proximity does not equate to emotional closeness. It was also a closer look into the fatigue that comes along with the failures we bear whilst waiting for the other. That sometimes grows into a greater desire, especially when it feels like we have to work for love in order to make it more meaningful or real.

What My Pussy Lovesis a self-published photo book that features your cats. The visual language for this photo book is incredibly striking in that it recalls Victorian portraits (the oval frame) and a comfortable domestic environment (the floral backdrop). Talk us through how you conceptualised this work, and why making reference to the aesthetic of a home was essential to that.

I started working on What My Pussy Loves in 2011, and this was around the same time I was making The Innocence Project. I was in the midst of shooting for The Innocence Project, and one of my cats got curious about my makeshift photo studio. She jumped up onto the prop table and sat very still, almost as if she was posing for the camera. There was this incredibly enigmatic quality about that scene, and I just thought to myself — okay, I'm going to shoot this.

At that time, there were two major events that were unfolding in my personal life. My paternal grandmother was nearing the end of her days, and my father would spend a lot of time with her. On the other hand, I was involved in a difficult relationship with my then-boyfriend. The contrast between these two situations got me thinking about ideas of commitment and fulfilment in the context of relationships. What are the extents to which one is willing to go, especially when it's so easy to give up? Plato once said that love is divine and selfless. Lacan, on the other hand, wrote that love is egoistic and narcissistic. When we say that love is selfless, are we merely searching for some form of reciprocation or for our own self-serving purposes?

That accidental situation in the studio led to the project, What My Pussy Loves. I thought my fur kids were the perfect sitters for this series. To me, they are family. The entire project was documented over three years, and involved three of my other cats. It fully depicts the trials and tribulations of caring for someone — right up until death. One of the images in the project features the urn of my late cat, Blackie. Blackie never got along with the other cats very well because he wanted all the attention for himself. For identification purposes, the vet left my full name of Blackie’s urn. Seeing my name on that urn was surreal. When someone you love so much leaves you, it does feel like a part of you dies away as well. This project was something I felt I had to just get out of my creative system in order to move on. Despite its cheeky title, the project is very personal and dear to me and it holds a lot of sentimental value.

When What My Pussy Loves was released, it was met with a very warm reception. That was really nice, and it could probably be attributed to the number of cat lovers who enjoyed the project. However, I want to circle back to something I said earlier about labels. Because of the success of What My Pussy Loves, there was a point of time where people called me the “Pussy Lady” or the “Pussy Artist”. It sounded like that was all I was known for, and that really irritated me. As such, I’ve experimented with different ways of presenting this work over the years, and this is the same for most of my other works as well.

What My Pussy Loves, Liana Yang

2011 - 2014

2011 - 2014

Art that discusses the erotic or the sensual can often be seen as, or even written off as, merely provocative. Having said that, that doesn’t seem to be the only thing you’re trying to do with your work. What is the place of intimacy and tenderness within your practice, and do you see them as resisting, in a way, careless readings of your work?

Intimacy and tenderness are just some of the layers that I weave into my works. I like to think of it as a quiet storm that’s brewing.

In the realm of modern romance, there is never any guarantee. There is now a larger degree of freedom about relationships — both in terms of the kind of relationships we want, and also in relation to how we want to pursue them. When things don’t work out, some of us hold on to rather toxic anchors to help buoy us through. Some of these anchors are masked under the guise of intimacy and tenderness, but in truth, can be rather violent.

I won’t deny that my work has been dismissed as provocative. Some have even described it as a contrived tease. I’ve come to terms with that, because I know that my works are not created with the intention of being one-dimensional. I don’t create works to amuse audiences either. My hope is that these works open up discourse around societal norms. I see creative potential in the banal and the everyday because these are all accessible points in starting conversation. Art rarely makes sense, and this is similar to intimacy and love. These are all things that are irrational.