Liyana Ali's art practice revolves around the idea of examining negative and positive shapes and spaces. Her practice includes being sensitive to ephemeral factors such as the impact of our environment and how it affects the materiality of the work. Another aspect of her interest is how the artist's body and movements impact the discovery of shapes formed by her process of material handling, casting and spatial arrangement.

As viewers stepped into The Warehouse for State of Motion: Rushes of Time, the first work they would have seen was Liyana Ali’s In-Between Configuration. Unassuming visitors might think of her work as building materials leftover from the process of installing the exhibition. On the exhibition’s opening night, a couple of visitors nearly stepped on the artwork — testament to just how seamlessly the work blended into the space. In a nutshell, this highlights the essence of the artist’s modus operandi. In this interview, we speak to Liyana about her influences and her philosophies towards making.

As viewers stepped into The Warehouse for State of Motion: Rushes of Time, the first work they would have seen was Liyana Ali’s In-Between Configuration. Unassuming visitors might think of her work as building materials leftover from the process of installing the exhibition. On the exhibition’s opening night, a couple of visitors nearly stepped on the artwork — testament to just how seamlessly the work blended into the space. In a nutshell, this highlights the essence of the artist’s modus operandi. In this interview, we speak to Liyana about her influences and her philosophies towards making.

You’ve been inspired by Japanese aesthetics throughout your practice, and I was wondering if you could elaborate on this. There is a clear resonance between your works and that, for example, of the Mono-ha movement. When you refer to Japanese aesthetics, what aspect of this aesthetic are you referring to?

As an art student, I studied painting and I was starting to question if painting was dead. At that point in time, I did most of my canvases myself. I found myself falling in love with the smell of the raw canvas, especially before it was primed. When canvas stretches, the material has this sense of elasticity, toughness or tension. If you allow the canvas to just fall to the floor, it takes on very interesting folds and layers. You don’t have to do anything, because that’s just the way the material behaves. Prior to this, no one told me that materials could behave this way. That was how I found myself looking at my material for their materiality. I couldn't explain it, or what was going on. It just felt natural. I wanted to make art that looked like or behaved like painting, but was not painting. I loved how canvas, as a material, had its own character. I didn’t want to break the material into its simplest form, but I wanted to see how far I could stretch it. How far can a material go, or what is its limit? Again as an art student, paint is an expensive material. Maybe it was because of this that I started to look closer at or turn to other materials. When you start working with canvas, you start to notice the material for its own qualities. It no longer is the support or the background for an artwork. It is the artwork.

Around this point in time, a couple of friends introduced the theory of wabi-sabi to me. I have always enjoyed philosophy and theories, but they came primarily from a Western or European tradition. I always felt as if these theories were far removed from my reality, particularly because they were born out of a very different context. When I was first introduced to the Japanese idea of wabi-sabi, I had a very superficial understanding of Japanese culture. I knew about anime and manga culture, for example, but obviously that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Reading about wabi-sabi made me incredibly happy. I enjoyed its ideas about embracing imperfections, and I was excited to begin referencing this within my own practice. Compared to the European theories I was used to reading up on, this also felt like a philosophy that was closer to home.

The first time I went to Japan, I brought my mum along with me. I was determined to find and see wabi-sabi in action. I asked a family friend who had been based and living in Japan for awhile if she could define wabi-sabi for me. It was very difficult for her to define it, and I have to be honest, I was disappointed that I couldn’t get an answer. I had read all of these books, and I had all of these expectations. Following that trip, I’ve gone back to Japan a couple more times since. Every time I go to Japan, I go in search of something that could encapsulate the idea of wabi-sabi for me. Instead, I always come back with something else. Perhaps there is no one definition, and it is something that has to be embodied, unspoken and experienced. When I speak of the Japanese aesthetic, I’m not referring to kimonos or cherry blossom trees. With these trips, I always find myself bringing back experiences and visuals that are incorporated into my own practice. This extends to the colour of the cities I visit and how they behave. Recently, I’ve developed an interest in how the old is interspersed with the new in Japanese cities.

Coming back to your question of what aspect of the Japanese aesthetic I’ve referenced in my works, I don’t think I can narrow it down into a straightforward or singular answer. It’s an experience. It isn’t just about respecting nature and leaving it untouched, but that when there is human interference, it leans into nature’s best qualities. I always create my works with the space in mind. The work should not invade or intrude upon a space. As an artist, it’s important for me that the artwork is mindful or part of its surroundings. I prefer being assigned a space by a curator or a gallerist, as compared to picking out my own space. My works just don’t behave in that way. It isn’t about making the space conform to my work, but about creating a work that is one with the space it is placed within.

Your work responds to space and construction. From what you’ve said, it seems like the space always comes first and the work cannot exist without the space. When you’re given a space to work with, what do you look out for when you’re coming into that physical environment? Are there particular elements you’re drawn to, or structures that you pick up on?

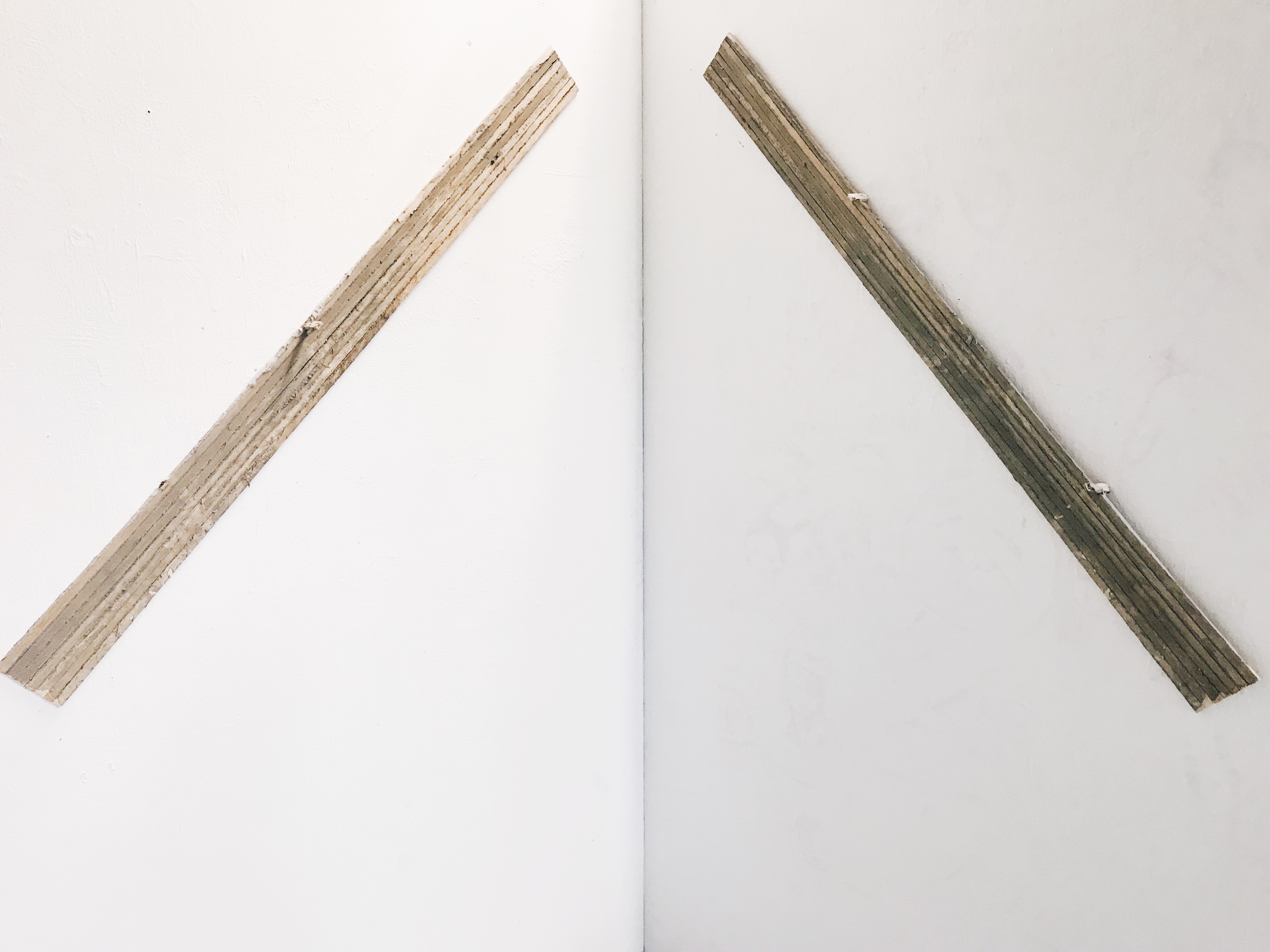

For the works I created for the recent State of Motion: Rushes of Time, I loved the lines that ran across the rooftop of the venue. These lines, along with the angle at which the windows were placed, really draw one’s attention to the floor. The floor is an area or an element people tend to overlook when they step into a space. More often than not, we’re not mindful of the floor space. When the exhibition opened to the public, there were quite a few instances where viewers came close to stepping onto the works themselves because they were placed on the floor. Even at an art space or an art event, we aren’t all that mindful of our surroundings. Viewers can be distracted or on their phones — people are just busy.

With every work I do, I want to stop people in their tracks by encouraging them to look closely at the space they’re coming into.

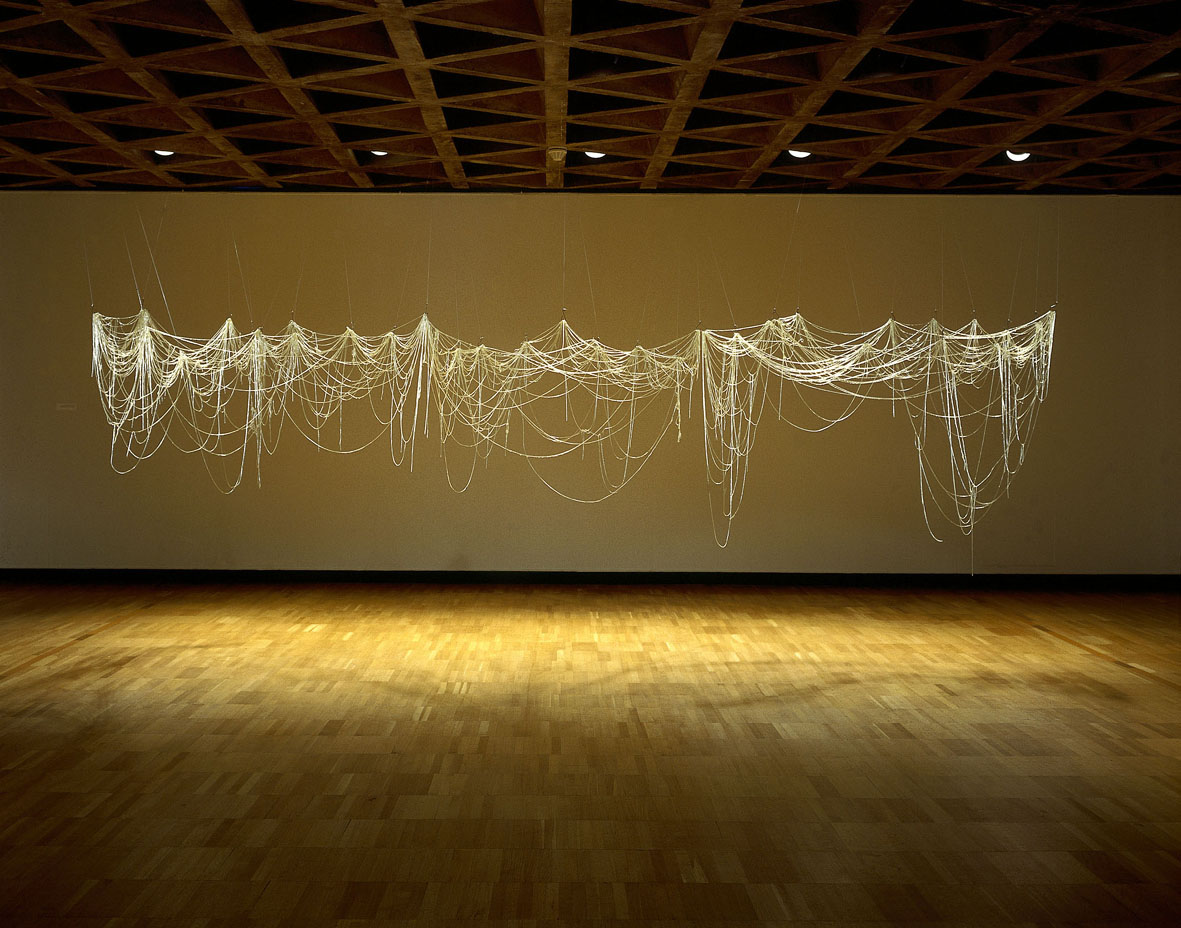

¹ In-Between Configuration, Liyana Ali

2020, Installation View at The Warehouse

Photography: Joseph Nair

2020, Installation View at The Warehouse

Photography: Joseph Nair

Could you elaborate on this notion of mindfulness? Increasingly, we see a lot of creative ways in which artworks can be displayed. It is no longer about placing an artwork in a frame or on a plinth, but art can be on the floor or hung from the ceiling. This creates a different perception as to how art can be encountered, but it doesn't always result in mindfulness. When you speak of mindfulness, what does that mean for you?

For me, it’s about the approach. Mindfulness is about questioning why things have been done a certain way.

The materials that I use in my works, such as wood and concrete, are quite cheap, and you see them all around us everyday. My family is incredibly supportive of my practice, but they don’t always understand my works. When my grandmother saw my works at The Warehouse, she asked if that really was my work. She was confused because she thought that outside of The Warehouse context, if she saw it along the side of the road, she would think of it as debris or trash. That’s actually why I use such materials. When viewers begin to ask why artists use certain materials and reference certain ideas, it can be freeing. Art is not just a spectacle.

Materials are an incredibly important part of your practice, and you put a lot of thought into the sort of materials that you work with. How do you approach the materials they use? Do you consider yourself to have a philosophy towards materials and materiality? If so, how would you describe this philosophy?

Stretching and not breaking a material is important to me because I want to work with these materials in their purest state. This means using simple shapes such as lines or blocks, so that these visualisations don’t suggest what the material should be.

When I’m creating a work, and it doesn’t physically tire me out, the work will not feel right.

Making works is a tedious process for me. When I work with the material, it sometimes feels like the tasks I have set for myself are never going to end.

Before working in concrete and wood, I made a lot of works with fibres. Over time, I got used to the process of working with fibres. It became really easy for me to strip a canvas down into strips, and that was when I knew I had to move onto something else. It felt too familiar.

² O.O.P. (On One Plane) (slabs and moulds), Liyana Ali

2019, Installation View at Chan + Hori Contemporary

Credit: Chan + Hori Contemporary

2019, Installation View at Chan + Hori Contemporary

Credit: Chan + Hori Contemporary

³ Right After, Eva Hesse

Milwaukee Art Museum, 1969

This stretching of materials is something that can be seen in the works you picked out for our conversation by Lee Ufan and Eva Hesse. Both of these artists were interested in how materials could open up these in-between spaces of relationships, dialogues and conversations. Tell us about what makes the works of these two artists enjoyable for you, and where you were at in your practice when you encountered them.

I encountered the works of Eva Hesse when I was questioning painting as an art student and beginning to move into sculpture or installation work. She started off as a painter herself, and I was interested in why she shifted away from that medium as well. Hesse has a way of working with materials that feels incredibly intimate and personal. Her works are beautiful. Her hand resonates even in the subtle folds or the draperies of her work. She allows the material to speak. In Right After, these threads are hung suspended and in these curvilinear shapes. I love that work so much because she allowed the work to fall, drop and loop on its own terms. There, of course, is gravity here at play. But her work has an incredibly poetic element to it, and it blew my mind away.

She was working at a time where Minimalism was all the rage. A lot of her fellow artists were interested in clean lines, cubes and white spaces. She uses materials that, in my opinion, have minimalist characteristics. Yet in her hands, they become something else entirely. For me, Eva Hesse’s work captures what it is to be human and what it means to live life. We aren’t perfect, and it isn’t always neat and clean. We’re always told to colour within the lines, for example. She was the first artist I encountered who was able to do that through an incredibly material practice.

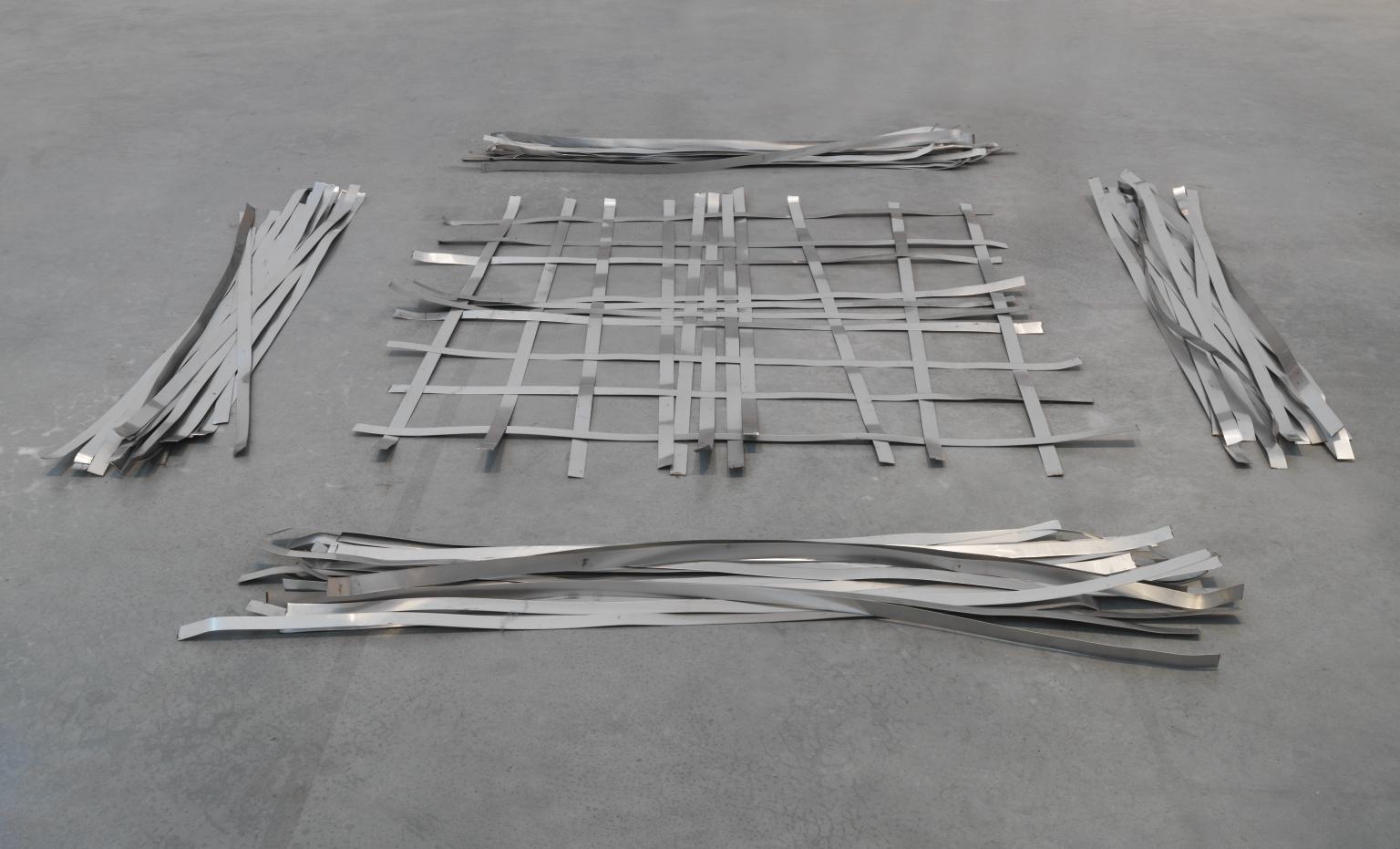

⁴ Relatum, Lee Ufan

Tate, 1968/1994

Lee Ufan’s work is also very conceptual. The work you’ve picked out for our conversation, Relatum, is simple to assemble or put together. A viewer can easily make out how the artwork was formed. Yet it is about how the artist intervenes to create something special out of the ordinary.

Making something special out of the ordinary is something I find very important as well. I learnt of Lee Ufan a lot later into my practice. Lee measures or regulates his breath whilst he paints, and that was the idea that drew me to his work. That intrigued me, and when I did more research into the artist, I found his sculptural and installation works as well. I really enjoy how he works with objects and materials, although I’m sure there are other layers to his practice. The political, for example, is prominent. Lee is a Korean who has been based out of Japan for a very long time, so his work touches on these notions as well.

Amongst all the artists who were part of the Mono-ha movement, I still find Lee’s work the most striking. The National Gallery Singapore hosted an exhibition on Minimalism last year, and I was excited to hear that quite a few Mono-ha works were included. It was a survey show, so there were a lot of works around. Even though Lee Ufan’s works were included, I wish he was given a room to himself.

When you place materials or objects together, they take on their own character. That’s what happens with Relatum. Lee intervenes to create this composition, but he allows the materials to speak for themselves. Materials are as unique and individual as we are. When I see these strips of steel, I think of the time and labour that has gone into slicing them up. Metal, or steel in this case, is always seen as a hard material. When strips of metal are interspersed with each other, almost woven into a tapestry, it reveals that these materials also have a softer side.

⁵ Contingent, Eva Hesse

National Gallery of Australia, 1968

Out of all the works you picked out, let’s dwell for awhile on Eva Hesse’s Contingent. Contingent balances a lot of delicate but interdependent concepts — which is similar to how your works deal with varying ideas all at the same time. Do you see your individual works as being continued questions along your pursuit of knowledge, or as one possible answers to your various questions?

My practice is about gathering information, and using that to inform my understanding of how materials behave and how space works. There are times in which I’ve created a work or I’ve worked in a particular material, but it just doesn’t pan out. When the work is placed into a space, it just doesn’t come together at all. It then becomes a question of why the space hasn’t accepted the work, and that can come down to so many different factors. It goes back to my experiences with the Japanese aesthetic. When you think about the fact that nothing is permanent, it helps with resolving these questions.

It’s about letting go. Sometimes, materials simply will break because they want to and that’s okay.

It is important to not hold on too tightly to certain artworks because some materials just do not last. It sounds crazy, and it almost sounds as if I’m being flippant about my works, but that’s not the case. This is how materials behave, and I respect it. A work can feel like it is done with its original form, and that it would like to become something else.

⁶ An Offset, Liyana Ali

2019, Installation View at Winstedt Road

2019, Installation View at Winstedt Road

Let’s talk about working with wood. What is your process of working with this natural material, especially in terms of sourcing, processing or salvaging wood?

There are other instances in which I work with rigid, sturdy wood as well. Colour also plays an important role. Sometimes the contrast between the wood and cement isn’t strong enough for the concept. Sometimes it feels too rigid, or the colours aren’t quite right.

On top of thinking about the pliability and colour of the wood you work with, what are your considerations regarding the grain of the wood?

The grain of the wood matters most when I'm cutting it into strips. I always cut along the grain as compared to across.

We see the term “site specific” being used quite loosely now, with a wide variety of artworks or art practices being described as “site specific”. As an artist who creates works that very much respond to space and construction, what does the term “site-specific work” mean to you?

Although my works are sensitive to space, I don’t think of my work as being site specific. To me, a site specific work means that a particular work can only fit into a particular space. For example, if the work needs to be exhibited in the corner of an exhibition space, that’s a site specific work to me. Because I work with any space that is given to me, and create works for these spaces, I don’t consider my works to be site specific. I think as a term, it isn’t precise enough. When I think of a site specific work, I think of works by artists such as Robert Smithson. He needs to be close to water or sand in order to create his works. A site specific work brings to mind the need for specifications or criteria. My works can be in any space at all, and they’re supposed to become one with the space. It’s really about the in-between or grey areas.