Lucy Davis is a visual artist, art writer and founder of The Migrant Ecologies Project. Her practice encircles ecologies, animal and plant studies, art and visual culture, materiality and memory — primarily but not exclusively in Southeast Asia. She is currently Professor of Artistic Practices in the Master’s Degree Programme in Visual Cultures, Curating and Contemporary Art at Aalto University, Finland.

We sit down with Lucy one rainy Thursday afternoon and speak to the artist via Skype. From the other side of the planet, she shares with us about the artists whose work has inspired her, and of her fascination with the multifarious connections between communities and ecologies.

We sit down with Lucy one rainy Thursday afternoon and speak to the artist via Skype. From the other side of the planet, she shares with us about the artists whose work has inspired her, and of her fascination with the multifarious connections between communities and ecologies.

Tekukur, Lucy Davis, Kee Ya Ting and Zachary Chan

Tekukur, Lucy Davis, Kee Ya Ting and Zachary Chan2020, Installation View at Esplanade Jendela

Bird People Series 4/8 (Dedicated to Hamwal Kassim, alias Rahim)

Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1996 - 1998

Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1996 - 1998

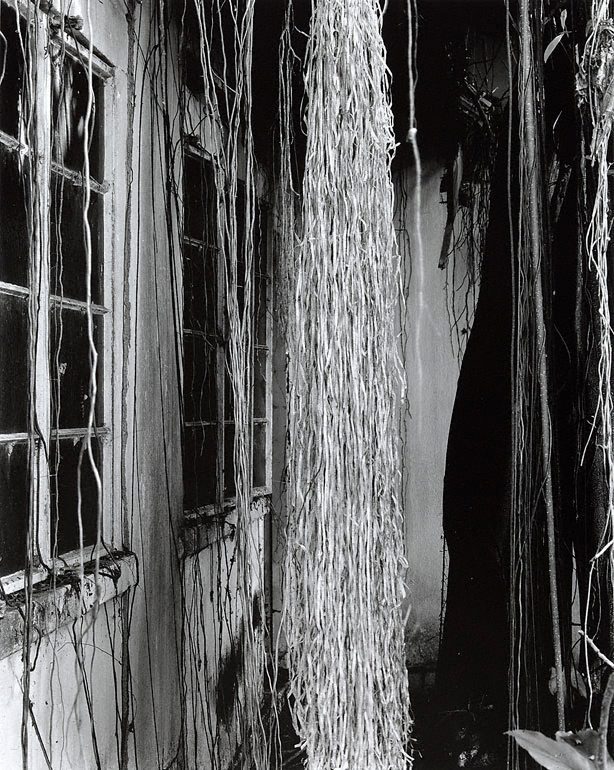

In her work Forest, artist Simryn Gill photographed strips of text that she grafted into the natural environment. These pieces of paper, wood fragments, are at once returning to their roots and foreign; they rapidly disappear, eaten up by insects or otherwise weathered away in the tropical climate of Singapore and Malaysia. This brings to mind your own musings on the notions of “migrant” and “ecologies” — tell us what these words mean to you, and how they connect with one another.

First of all I want to be really conscious that I'm not using any of the works I've picked out as this sort of foil via which I talk about my own work. I want to talk about the works in themselves as well.So perhaps to begin with, for Simryn's work, and in fact for all of the works I've chosen, there is an immediate aesthetic accessibility. There are both immediate and ongoing resonances in these works, and of tactile accessibility. If I think of Simryn’s Forest: it is very much an aesthetic experience, of the quality and materiality of paper versus the cool flesh of the plants. What I find so inspiring about her process is the way it slips between material and metaphor. You can't put Simryn's work into one box and say it is all about this: it’s not definitively about identity, it's not definitively about plants, and it's not just about an ironic “nativization” or “indigenization” gesture or a transplanting of a canonical text like the Ramayana or Darwin's On The Origin of Species. It's something elusive that becomes in the in-between; in the meetings of these two disparate entities.

Another thing that is the case with almost all the works that I've chosen is that they're very simple gestures. But that very simple gesture in Simryn’s case then then opens up this irreducible and complex dynamic between migration, text, vegetal worldings, nature, culture, and ecology. Simryn plays with these binaries of nature and culture, but it's not a kind of clearly deconstructionist gesture. The art critic Lee Weng Choy talked about Simryn being a flirt in that she's flirting with these concepts and they're almost left unresolved. So you've got this very literal gesture — of sticking these texts onto plants — that then opens up this material and metaphorical dynamic, and it's left unresolved. There's also a sense of temporality. The work is ephemeral. It won't be there for ever. It suggests a future that has to do with a productive decay, a productive recomposition.

I want to also say that in all of the examples I've given, there's no direct link to the work of The Migrant Ecologies Project. These inspirations, among many many others, are there in the background while we are making work, like invisible friends. But you could say that in almost all of the projects we do, the initial gesture is almost literal and very obvious. For example, we DNA profiled a wooden bed we collected just so we could find out where its wood comes from. We’re trying to tell very simple and materially-centred stories. This allows us to open up the slippery complexities between nature and culture, and even collapse the way in which we approach the world through a framework of binaries and dualities.

Forest seems to toy with these ideas as well, with the plant interventions occurring in these places where it seems as if Nature is reclaiming these man-made spaces.

Yes, there are multiple agents in Simryn’s work. It makes us aware that we're not in control of all this. Non-human entities are always already reclaiming, reconstructing, recomposing us — some of us are stuck at home right now because of this virus, for example.

2019

2012

And speaking of that, the current COVID-19 situation reminds me of these other events that are very vivid on the Singaporean psyche, like the flash floods in Orchard, the Bedok Reservoir suicides and the Bukit Brown cemetery exhumation. There are events that inspired the works you've picked out, Ultrasound and Bukit Brown Index #132: Triptych of the Unseen. How do you see these works responding to the world around us?

One of the reasons why I really respond to Bukit Brown Index is again, primarily, the aesthetic. I am friends with Jennifer Teo and Woon Tien Wei (founders of Post-Museum), and certainly we have a lot of things in common. We've all been involved in kinds of gentle advocacy in our practice. What really drew me to this work, however, was the feel of the installation. If you wanted to draw a direct connection, it would be that we both have an interest in salvage as an ecological and aesthetic strategy. What I mean by this is a sort of karang guni aesthetic in terms of putting things together. With a little bit of mess, we can allow space for the imagination. It is a cobbling together of sorts — and that concern with craft then brings us to Yee I-Lann's work and, to an extent, also Simryn's work. The imperfect hand is very present in what they do. This aesthetic has a kind of fragility. We talked about this in the seminar we held at the Esplanade for the show Railtrack Songmaps Roosting Post 2. One of the titles for the forum was Salvage as Artistic and Ecological Method, and we spoke about salvage as a practice. How can we cobble together the remnants of place and story whilst it is being destroyed? We spoke about grief-work as well. This refers to how one works with this feeling of loss, and the ways in which we make these salvage energies transformative and future looking. We do not want these feelings of loss to become funereal, monumental, or even tomb-like. Jenn and Tien are clearly also dealing with all these themes of death and hierarchies of human and non-human death. For example, who’s death is more important? Who gets to have a good death? Yet the work is still very future-looking because in their tellings, the spirits live on. These spirits are talking to you. The work is not something that is encased in a glossy photograph book that imprisons the dynamics and pleasures of the Bukit Brown. The possibilities of Bukit Brown are still there, even if they're there as ghosts and demons. What Post Museum does with this project is provide space for this tremendously precious connection of nature-cultures. These connections are allowed to seep outwards, and to find other places to live.

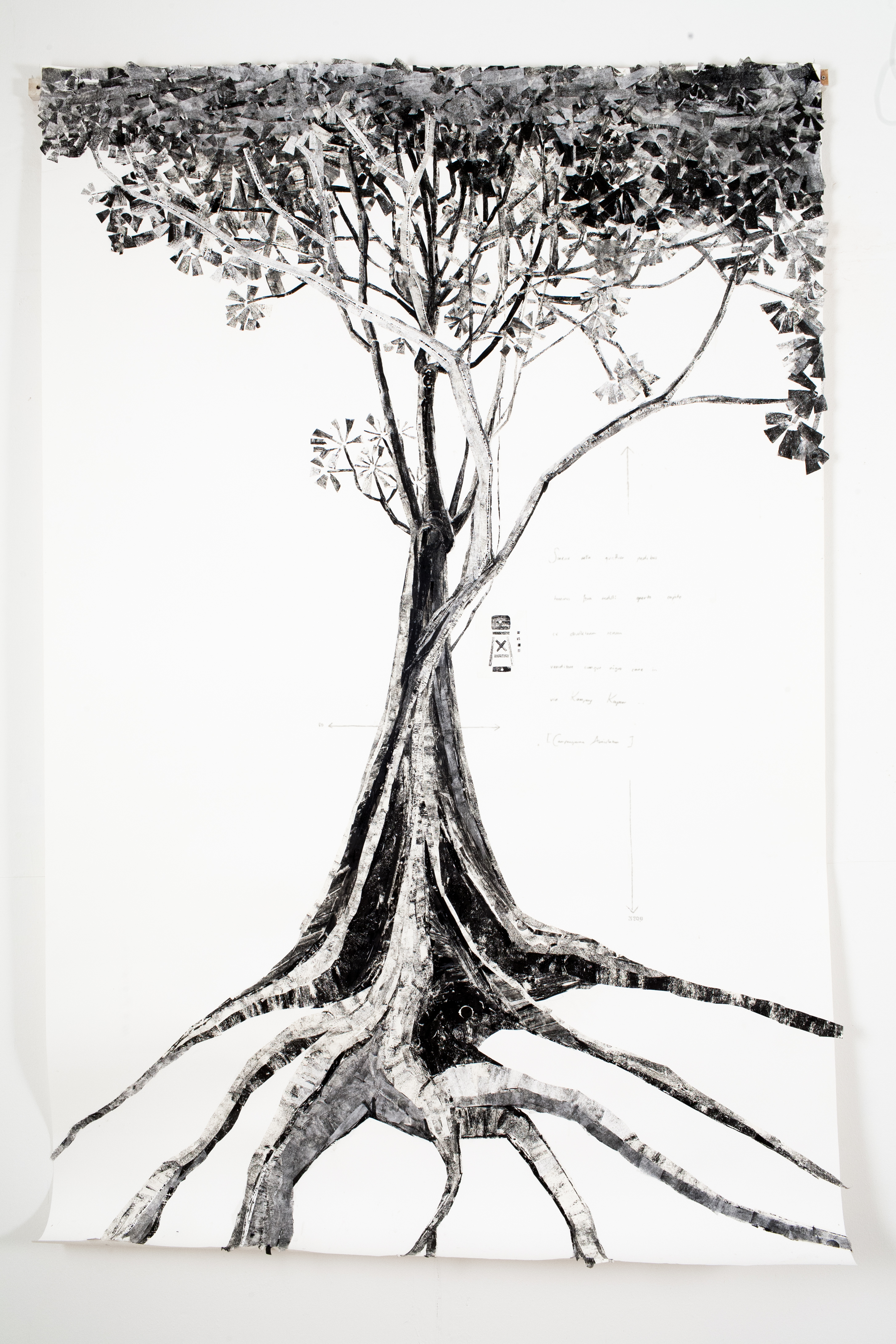

I see Genevieve Chua's work as very different. The only connection that Post-Museum and Genevieve’s Ultrasound have is a kind of metaphysical dimension. Ultrasound has an otherworldly dimension, not of ghosts necessarily, but the environments are certainly ghostly. It speaks more to the woodblock and wood print collage trees that I worked through in the Stories of Wood series. It speaks to urban ecologies and storytelling, and I have an immediate reaction to Genevieve's work that is very different to the Bukit Brown work. There is a dimension of awe to it, particularly with regard to this world, this space, and this cavernous entity that she conjures. It is very embodied. Yet it contains dimensions of the public, private, personal and political. By moving into abstraction, Genevieve is also able to evoke multiple registers at once. It is a feminist vision. It also suggests climate politics yet draws from very specific urban Singapore events. The work also has this sublime, painterly dimension.

⁵ Sta aaart?, Lucy Davis, Kee Ya Ting and Zachary Chan

2017, Installation View at Tanglin Halt Residents’ Committee Space

Bird People Series 3/8 (Dedicated to Alan Ow Yong and Ow Yong Sue Lin)

⁶ Ki ki ki kii, Lucy Davis, Kee Ya Ting and Zachary Chan

2017, Installation View at Tanglin Halt Residents’ Committee Space

Bird People Series 2/8 (Dedicated to Esther Kamala)

2017, Installation View at Tanglin Halt Residents’ Committee Space

Bird People Series 3/8 (Dedicated to Alan Ow Yong and Ow Yong Sue Lin)

⁶ Ki ki ki kii, Lucy Davis, Kee Ya Ting and Zachary Chan

2017, Installation View at Tanglin Halt Residents’ Committee Space

Bird People Series 2/8 (Dedicated to Esther Kamala)

When I requested from you a selection of artworks you have been inspired or influenced by, you mentioned that you were engaging with quite a few feminist writings as of late. You also spoke about artists as working within interconnected fields and the false notion of artist as genius. Talk to us more about who you have been reading, and the way you see yourself as an artist in relation to your field.

I’m coordinating a course in May, and we’re putting together one-week intensive workshop titled Climate Resiliences. The workshop hopes to co-devise strategies for staying with the trouble without going under or running for the hills. I’m coordinating this together with Sanni Saarimäki, a psychologist hired by Aalto University to respond to climate anxiety amongst students, and Professor Julia Lohman who is a designer working with seaweed and an initiative she calls the Department of Seaweed. However, all of us, are coming there as peers. Anything that comes out of the workshop would be co-authored and open source.

In terms of writing, Donna Haraway is someone who has written about how a work becomes richer with more more source-lines being traced into it. She also speaks a lot as to the importance of paying credit. She is very good at crediting her own students. She always makes it very clear that she's really just part of a process of becoming, and her works weave thoughts that she has drawn from many places. The visual arts are particularly bad at this kind of referencing. Haraway complains about male academics, but for visual artists there often is no system of referencing at all. There are no automatic mechanisms for that in a visual arts show. There's the star artist's name, and they're imagined to have dreamt up everything themselves by virtue of their own genius.

The way I'm coming into this positively is because of Donna Haraway and my students' collaborative practices.

For me, speaking of your inspirations only make your work richer.

Having said that, we’ve had experiences with The Migrant Ecologies Project where artists have ripped off of our works without referencing them It’s not always a conscious process. When you work closely with other artists or when you don’t have a wide field of other references, there are often blind spots. Things happen, and you are not conscious of everything that goes on. The Migrant Ecologies Project have also, ourselves, been caught out before. We've had a situation where I realised a year after the artwork had been out, that for one of the artists who I've been working with collaboratively, had a dimension of their work that was very similar to their former teacher's. It was quite clear that we had to go back and credit that person on our website, saying that the work drew from this legacy. There's really no issue. In fact for me, it makes the work a part of a richer weave.

What this means in practicality however is that I've had fights with some curators and designers because all these credits tend to become a very long list in our exhibitions. I really do think it is important, and increasingly so, for these co-authored projects like Railtrack Songmaps with so many human and non-human partners, interviewees, and voices involved. It is not easy, but I think it's an ethic that is something the visual arts community can think more about.

Do you think this ties in with what you previously mentioned about feminine ethics of care and collaboration? How does this tie in with a feminine or feminist tradition for you?

I don't want to essentialize this process, of course. It's not something that just women do. However, there has been a particular feminist critique of the individualised, competitive, patriarchal society; a critique of capitalism, competition, profit accumulation, and an idea of progress. There is also a feminist attempt to bring back or restore values that have been “feminized”. By this I’m referring to values that are sometimes is associated with notions of being seen as soft, feminine and therefore trivial. These definitely are not necessarily biologically feminine characteristics, but they are seen to be so, and therefore downgraded. These are values like sharing and collaboration, but also practices of craft and the collaborative processes that go with making something in a craft context. There is a connection there as well.

The Migrant Ecologies Project works in a very collaborative way. There is a huge list of collaborators listed on the website for each work. These projects for you also span, as you said, across many years. Why do you choose to work this way in respond to the call of migrant ecologies?

It just seems more fun, you can make things so much richer, and almost more ecological, if there are more of you, and if you come from different perspectives.

⁷ "Four Legged Stool Tree" Terentang/Campnosperma Auriculata, Lucy Davis

2009, Installation View at Post-Museum

⁸ Bangku terentang, Lucy Davis

2009, Installation View at Post-Museum

2009, Installation View at Post-Museum

⁸ Bangku terentang, Lucy Davis

2009, Installation View at Post-Museum

⁹ Tikar-A-Gagah, Yee I-Lann

2019

On that note of collaboration and craft, let us talk about your selection of Yee I-Lann’s Tikar-A-Gagah, which is a critical engagement of Southeast Asia’s postcolonial history, notions of memory and geopolitics, and the power relations in artmaking. You have long been interested in the notions of human connections in the region of Southeast Asia. What about this work intrigues you?

I want to talk about how I respond to where I-Lann is right now by telling you about the work of a colleague I mentioned previously: Julia Lohman’s Department of Seaweed. As I see it, Julia is in the same sort of zone as I-Lann in the moment, in that Julia has really found her material, her politics, her poetics and her method. The seaweed that she's working with, which are metre-long kelps, can absorb more carbon than rainforests. They can protect and help restore coral reefs by hindering invasive species such as sea urchins. They can also provide safe spaces for baby sea creatures. When you meet Julia, it is wonderfully energising. It becomes clear quite quickly that she has found her thing. That's what I enjoy so much about encountering I-Lann’s latest work as well. This is not limited to the actual works themselves, but also the place and the processes that she's embedded in, especially having moved back to Sabah and working with this female community of expert weavers. I've known I-Lann’s work for a long time and it just seems like all these things she cares about — community politics, marine ecology, and feminism — are coming together right now. It's superb and it makes for an absolutely beautifully rich experience of the work.

As for Tikar-A-Gagah, I really prefer the back side of the weave. There you can really see its intricacies. In order to appreciate it you have to kind of dance with it. The light catches different parts in different directions. You'll have something that looks like a buffalo in negative space and then when you turn it becomes positive, so there is an kind of animated dimension to it. Craft gets feminized and then seems soft and non-intellectual, something mechanical. But in this work, you can see that there are worlds in there — mathematical and geometric worlds, worlds of power and resistance too. This collective crafting is a very intellectual and conceptual exercise.

The dislocated way the work is displayed in the National Gallery Singapore, however, probably doesn't do the work justice. It’s displayed more like a modern artwork. I would like the work to be in the middle of a room with both sides given equal access. I would also like to see more of the documentation of the production of the work, possibly in the form of video, along with the weave and also the extended ecologies that the work is entangled in. For instance, the women I-Lann is working with are, as I understand, also planting pandan along the coast as a way to stop erosion.

1996

In a way Amanda Heng's Let's Chat escapes these issues because hers, at least if you encounter the live version, is a performance. Amanda's gesture is again deceptively simple — the most simple thing you can imagine. You just have a table in whatever context you're in, be it fancy exhibition or shopping mall. Then you have people sitting around it, shelling beansprouts. Like many of her performances, she then repeats this gesture in different spaces and it charges different contexts in different ways. For instance, she's done this in an old neighbourhood of Singapore, which then channels a whole embodied memory of women’s work. This is going to be completely different and perhaps richer than the kind of dynamics going on in a gallery environment. However, that she can transfer this work from a local, specific historical context to an institutional environment also suggests how future-looking Let's Chat is. It's not locked in this nostalgic past where we used to hang out together in the kampong and shell beansprouts. It has the capacity to both be restorative but also to suggest ways that we might be able to integrate collaborative nurturing work in an othered future.

I experienced it in a show maybe five or six years ago. I was at one of these pretentious shows where everybody is all dressed up, holding champagne and doing air kisses. In the middle of all that was Amanda and some others sitting down and just shelling these beans. It completely changed the temporality of the space around the table. You are sitting in a circle, you are clumsy, but your hands are moving with this living material that is delicate and cool. You have got this movement of hands, laughing, chatting and delicate beansprout-like synapses that are going off in your head at the same time.

Amanda's performance keeps coming into my head when I think about the Climate Resiliences workshop we are working on at Aalto. In a way without directly intending to, Amanda has created an incredibly therapeutic environment and a safe space. You're doing this repetitive task with your hands, and this is something that feels good with your fingers. The world is probably going to hell but for now you're able to do this. When we're talking about resilience, maybe these basic strategies are the foundation upon which we build up to other things. Of course this isn't the only thing that you do about climate change. However strategies for community wellbeing, as opposed to individualised and ironically often competitive practices of self-care, are really important in these anxious and fearful times. All this from such a simple gesture!

I experienced it in a show maybe five or six years ago. I was at one of these pretentious shows where everybody is all dressed up, holding champagne and doing air kisses. In the middle of all that was Amanda and some others sitting down and just shelling these beans. It completely changed the temporality of the space around the table. You are sitting in a circle, you are clumsy, but your hands are moving with this living material that is delicate and cool. You have got this movement of hands, laughing, chatting and delicate beansprout-like synapses that are going off in your head at the same time.

Amanda's performance keeps coming into my head when I think about the Climate Resiliences workshop we are working on at Aalto. In a way without directly intending to, Amanda has created an incredibly therapeutic environment and a safe space. You're doing this repetitive task with your hands, and this is something that feels good with your fingers. The world is probably going to hell but for now you're able to do this. When we're talking about resilience, maybe these basic strategies are the foundation upon which we build up to other things. Of course this isn't the only thing that you do about climate change. However strategies for community wellbeing, as opposed to individualised and ironically often competitive practices of self-care, are really important in these anxious and fearful times. All this from such a simple gesture!

¹¹ Ranjang Jati: The Teak Bed that Got Four Humans from Singapore to Travel to Muna Island, Southeast Sulawesi and Back Again, Lucy Davis

2009-2015

¹² "When you get closer to the heart, you may find cracks..." Stories of Wood

Installation View at NUS Museum

2009-2015

¹² "When you get closer to the heart, you may find cracks..." Stories of Wood

Installation View at NUS Museum

You've worked as an art educator for a long time, and are also known as an artist, curator and a writer. How do you see the relationship between these different roles? Is there one which comes first for you, and fo you see your different roles as interconnected or discrete?

Two of the co-collaborators on The Migrant Ecologies Project are ex-students from the Nanyang Technological University’s ADM. I didn't actually teach Kee Ya Ting, who is the photographer and cinematographer of The Migrant Ecologies Project. She tells everyone that she actually avoided all my classes! I did, however, teach Zachary Chan. When he was a student we had a shared interest in nature-cultures and Southeast Asian art histories. Working with Zach and Ya Ting is an evolving process. Sometimes it is a bit of a struggle moving away from that teacher-student relationship. I keep trying to but sometimes they keep putting me back into that place. However I do want to say that in terms of the visual and cinematographic evolution of the project, Ya Ting's point of view has been absolutely central in her own right. She really does own the way that the films are shot and way the series of photographs have emerged. Equally so with Zach and all of the printed materials. I hope they would agree that everybody gets to have their own kind of artistic development in the work.

With Zai Tang, he works more individually, creating the soundscape in parallel, then coming back with it to see how it dances with the visual media. However although he works independently in terms of his artistic practice, he is key to the organisational and collaboration practice. We all have to share the organisation and admin. Unfortunately, with me being away, this also means that the Singapore-based team has to take on more of the organisation and administration than before, which has been a bit taxing on them.

Looking into the future, one of the things I thought about is if the second installation with the HDBs and the nests goes into a collection, what might be nice is that every time the work is re-shown there there is a collaborative more than human nest-making workshop, where I kind of create a basic template for how to make these salvage nests, but borrowing very much from Amanda and from I-Lann.

I think about what might become in a collaborative, regenerative kind of environment — with people from different backgrounds making nests together.

Speaking of your being away, how do you see location's impact on your work?

Location is huge. I’ve always been someone who engages and embeds myself and tried to find meaning where I am. I absolutely hate travelling. It is a real struggle for me to have everything that I care about and the stories that I'm interested in telling being on the other side of the world. While I'm very fond of my students and colleagues here in Helsinki, and I have my partner in Paris, if I had the choice I would not move at all. Of course I'd rather still be in Singapore. Perhaps at some stage I'll just have to let go, but I’m not ready to do so yet.

This attitude manifests in my work in a sort of attachment, both to places and objects, or assemblages, stories, and dynamics. I spent ten years working on one teak bed, and another six years, if not practicing then at least thinking about, a crocodile and/or a straw that we found inside the crocodile. Railtrack Songmaps Roosting Post 2, which is the exhibition currently on at the Jendela, is the most personal for me because it's right next to where I used to live. This project is also the closest that I've come to direct advocacy, because for me it is a nexus of culture and nature that is so very special and that is nearly gone.

It is also important to say that one of the reasons why the Railtrack Songmaps came about is not only because I've been living there for a long time and had conversations with residents and foragers daily along the Rail Corridor. I also taught a course titled Cities Bodies Memories whilst teaching in the Nanyang Technological University’s ADM. This meant that every six months we had students who went around investigating the relationship between urban life, bodies and memories in that area. Railtrack Songmaps is also a part of that legacy in that a lot of discoveries were ones that my students made during that project. One of the key interviewees was first encountered by two of my students Donovan Tan and Steve Lim during that project.

In the work itself, we place great emphasis on the importance of these local stakeholders along the Rail Corridor, and the loss that is currently felt amongst this class of people. You've got a low-income group of elderly residents who have been living along the Rail Corridor since the 1960s and who have a whole multitude of practices. Some of them really are nurturing and some of them, I’ll admit, are a bit dodgy. Nonetheless, all of them are passionately engaged in processes of place making. They're engaged in both Tanglin Halt and the environment around it, and in activities such as foraging for fruit, herbs and medicines along the tracks. Some of them cut lalang along the tracks on the second day of Chinese New Year to feed to the horse statues in the Taoist temple. There are also the songbird clubs, informal cricket matches by migrant workers, and shrines such as the tree shrines, the Datuk Kong shrines and the Hindu shrines.

There's this mushrooming of connections between the ecological world, the urban world and the spirit world along the tracks. All of this are cleansed in order to create this park for middle class people to go jogging, ride their bicycles, and take photographs that can be posted up on Instagram. The new biodiversity would be probably alright, but the stretch would have lost a very particular nature-culture mix. If you take the people out of the equation, it just becomes another park.

One thing we’ve been trying to do is to lift up the voices of the activists who care about the biodiversity, and feature this alongside placemaking stories of those who have been sidelined by the official top-down narrative.

A number of these individuals don't speak English, so they can’t go along to these government-led feedback sessions to get their voices heard. Instead, their plants are dug up or they get these officious bureaucrat letters from the Singapore Land Authority telling them to clear off and clear out. Their presence has become a disamenity to the day trippers who now frequent the tracks.

¹³ Railtrack Songmaps Nest-Infestations, Lucy Davis, Kee Ya Ting and Zachary Chan

2020, Installation View at Esplanade Jendela

Collaborators: Priscilla Teh Xue Ting, Aaron Yeo Zheng Wei and Seah Jia Neng

2020, Installation View at Esplanade Jendela

Collaborators: Priscilla Teh Xue Ting, Aaron Yeo Zheng Wei and Seah Jia Neng

Railtrack Songmaps Roosting Post 2 is now open.

The exhibition will run at the Esplanade Jendela (Visual Arts Space) until 5 April 2020.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

The exhibition will run at the Esplanade Jendela (Visual Arts Space) until 5 April 2020.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.