Lukas Birk (Myanmar Photo Archive) on 1970s Burmese National Identity Card Photographs

Share: ︎ ︎

The Myanmar Photo Archive is an independent initiative by the multidisciplinary artist, Lukas Birk. Since its conception, it has amassed a veritable collection of photographs, slides and negatives. With an emphasis on perspectives on the micro scale, a large part of Birk’s work includes conversing with Burmese people from all walks of life and gathering their lived experiences. In order to ensure these images continue to speak to the present day context, Birk constantly activates the archive. This has resulted in multiple exhibitions and publications.

Lukas Birk is a photographer, conservator and publisher. His multi-disciplinary projects have been turned into films, chronicles, books, and exhibitions. His narratives tackle recorded history by creating alternate storylines and fictional elements, alongside commonly accepted facts. Lukas often researches his imagery through explorations into cultures that have been affected by conflict. His created ‘archival artworks’ have little to do with institutional processes but rather center around personal stories, the desire to preserve their place in history, and the artist’s own emotional attachment to them.

Lukas Birk is a photographer, conservator and publisher. His multi-disciplinary projects have been turned into films, chronicles, books, and exhibitions. His narratives tackle recorded history by creating alternate storylines and fictional elements, alongside commonly accepted facts. Lukas often researches his imagery through explorations into cultures that have been affected by conflict. His created ‘archival artworks’ have little to do with institutional processes but rather center around personal stories, the desire to preserve their place in history, and the artist’s own emotional attachment to them.

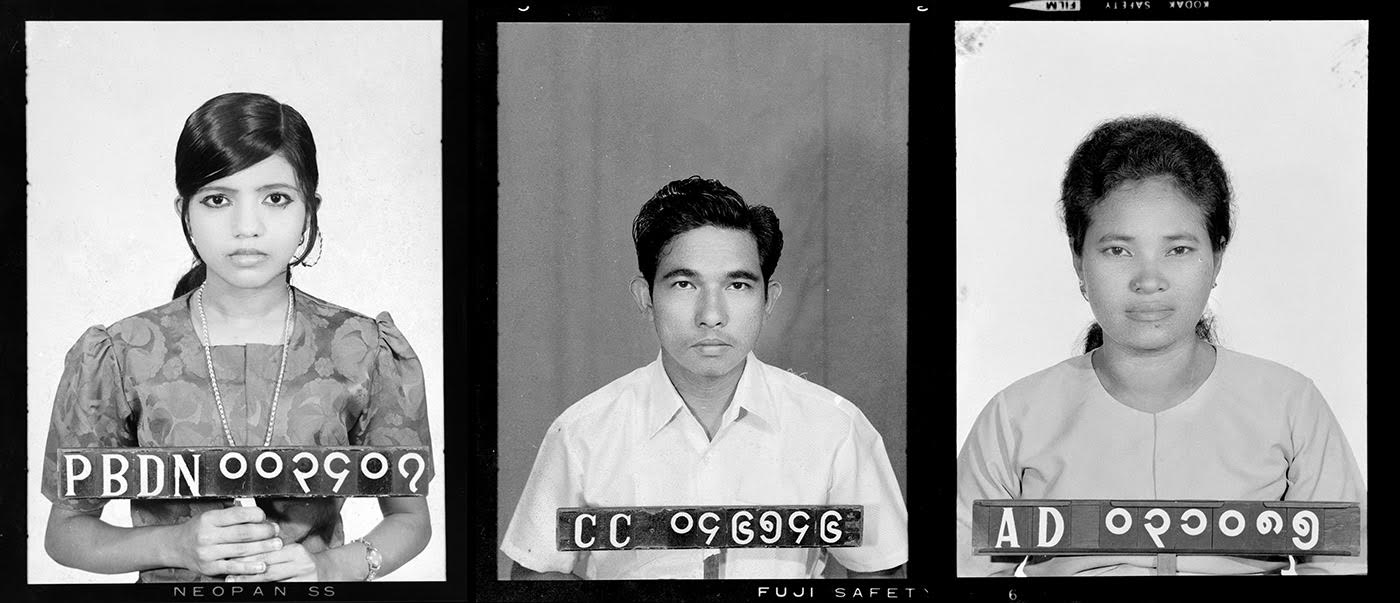

¹ National Identity Card Photographs

Yangon, c. 1970s

Credit: Myanmar Photo Archive

Yangon, c. 1970s

Credit: Myanmar Photo Archive

THE POLITICS OF AN IMAGE

Lukas Birk (LB): When I read an image, what I always find interesting is not just what’s depicted, but what are the sort of politics behind what we see. How did it come to be? What are the slow processes that led up to the way in which a particular photograph was conceived?

With these three images here, they were very much informed by the trajectory of Myanmar’s history. Myanmar achieved independence in 1948 and in the decades that followed, photography became really popular. It was accessible, and it was financially feasible for people to go to a studio to get their photograph taken. The dramatic rate at which photography spread was really exacerbated by administrative processes. As the newly independent nation grappled with its status, authorities needed a way in which they could document their citizens. As a result of this, the passport or the identity photograph became very important and this was the same in many countries around the world at that time as well. These administrative processes, which are closely linked to the political climate of the time, made it commonplace for people to go to photography studios in order to rethink who they are, what they want to be, and how they’d like to present themselves to others. For me, that makes this time a very interesting period in history.

The numbers beneath each individual portrait in this set of photographs allude to the fact that these were taken for the national identity cards that came around as part of the 1948 Union Citizenship Act. This piece of legislation laid out the perimeters of who was considered a Burmese citizen, and who was not. This decision was made based on factors such as ethnicity, religion and how long one’s family had resided in Myanmar. This imposed a large body of politics onto the Burmese people. These photographs are also reminiscent of mugshots, because one is numbered and labelled in the process.

From my own research into the photographic histories of Myanmar, it became clear that this led to the explosion of the use of photography. This is not to say that photography was not prevalent in Myanmar beforehand. Before World War 2, photography would have been mostly practiced by an elite class that could afford the technology at the time. As such, it is this later period that marked a more significant starting point for the introduction of photography to whole country.

THE ADVENT OF THE PHOTOGRAPHY STUDIO

LB: As with anywhere else in the Southeast Asian region, photography studios were initially set up by British photographers as early as the 1880s. In the case of Myanmar, you had German or Italian photographers running their own studios as well. These photography studios would have been frequented by the Europeans and sometimes by the Burmese elite, although that was very rare. These were also Indian and Chinese photographers active during this period of time in Myanmar. As a result of this, a colonial aesthetic dominated many photographs. Some photographs would be labelled simplistically as the “Burmese Man” or the “Burmese Beauty”. Of course we now know that these photographs were highly stylised and when we see images labelled “A Shan Man” or a “A Kachin Man”, the person photographed might not even be of Shan or Kachin ethnicity.

By 1905, we begin to see the first Burmese-run photography studios being set up. These Burmese photographers started out as apprentices under European photographers and with the establishment of their studios, we begin to notice a slight shift in aesthetics and subject matter. Where European photographers would document important events for European residents in Myanmar, Burmese photographers would document events that were important to the local Burmese residents as well. This marked a clear split between the work of European studios and Burmese studios. This is not to say that these Burmese photographers were not informed by their apprenticeships or training, but it is important to note that images of Burmese social or religious events were primarily taken by local photographers.

It is interesting that a large majority of the historical photographs that we recognise today were produced by an Indian-Burmese photographer, D.A. Ahuja. Ahuja was an astute businessman. When European photographers went out of business, he would buy up the stocks of their photographs and reproduce them in the thousands as postcards. There were studios similar to Ahuja’s all across Southeast Asia, even in Singapore. The visual impact of these images are so strong that they continue to exist in our collective conscience today. We think that this was what Myanmar looked like in the 1920s or the 1950s, and this is mostly because there are no alternative visual representations available.

In the 1970s when the environment surrounding creative expression was generally one of repressiveness, the photography studio also became an accessible tool and a free space. The studio became somewhere for people to be whoever they imagined themselves to be, and to get their photograph taken so that they could share that physical image with their friends. That became a small economy in and of itself, and it also birthed a culture of resistance.

² General Hospital, Rangoon, D.A. Ahuja

New York Public Library, 1910

³ Chief Court, Burma, D.A. Ahuja

New York Public Library, 1910

New York Public Library, 1910

³ Chief Court, Burma, D.A. Ahuja

New York Public Library, 1910

THE RELENTLESS WORK OF AN INDEPENDENT ARCHIVE

LB: There has been very little research done on what happens within Burmese photographic history after the European photographers leave. I think the Myanmar Photo Archive is the first attempt at dissecting and understanding local photographic practices, and how it was used across different periods of time. I started by looking at themes, timelines and how certain things had come to pass. At the same time, I conduct interviews with photographers who were active at the time and people who would’ve been students then. I would ask them about their aspirations, what they were doing at the time, and how photography became a part of their lives.

In Myanmar, there are hardly any visual historical resources available. If one was doing research into something that happened in the 1950s and was wondering if there were any photographs taken of it, a simple search online would turn up a couple of photographs taken by foreign photographers. Images taken by local photographers would rarely come up, and this is a result of not having the relevant material in public archives. What then happens is that the understanding of collective history, regardless if you are Bamar, Kachin or Karen, is limited. We might know the history of Myanmar through words in textbooks, but visual references are scant so there is a real gap in that understanding.

With the books I publish and the exhibitions I organise, I’m definitely aware of these gaps. I’ve curated exhibitions where photographs of people of various ethnicities are placed next to each other. In doing so, the idea that different people have historically lived alongside each other in Yangon is evidenced clearly. It is understood that there was a common life, common culture and a clear connection. This might seem obvious but if you’ve never seen it before in visual form, such an exercise helps. As a curator, you also have to think about how you can make these images approachable or accessible. The images in the archives are usually quite small in size, so I enlarged them to create these columns that were larger-than-life. It made the exhibition fun, which definitely helped get people engaged. Even if people are taking a selfie and are engaging on a social media level, there’s still that physical action there of identifying with something else. When I speak to people who come by the exhibition, they always say things such as, “I don’t know the person in this photograph, but she looks like she could be my aunty”.

The key goal we’re working towards is building an online open resource for the Myanmar Photo Archive. In other countries, there are various online resources for such archival materials. However, it’s usually researchers that get the most out of these resources because they know what they’re looking for and how to look for them. It’s important to have a platform that has all the digitised images uploaded, with search bars, essays, articles and tags, and in both Burmese and English. On the other hand, I’d love for it to function similar to a social media platform, in order to link it to the websites that people actually use on a day to day basis. That’s something I’d really like to do for the archive. Particularly in Myanmar, online archives aren’t used as much as social media platforms such as Facebook are. It’s a big goal that requires a lot of funding, but I think it’s important to present these images in the way that people now digest information.

I’m also very open with allowing artists to work with the archive, especially in having them reinterpret these images in their own work. As long as the original or the personal image is not exploited, I don’t see a problem ethically with using images from the past to illuminate our present. We have to constantly go through these processes of reinterpretation, otherwise we can get stuck into old ways of thinking. I think we’re at a juncture now where we really have to rethink how history has been told.

Some of the shortcomings that I see with older, more established archives is that they have difficulty getting into this mode of reinterpretation. It is difficult for them to grow towards being more than just a repository. Museums struggle with this too. In Europe, almost every museum with the word “ethnological” in their title has been since renamed because we all know that those ways of seeing don’t work anymore. There have been some initiatives by artists, but it is still hard for people to relate fact to fiction. If you have an emotional interpretation, that’d be art. If you encounter a factual account, that’d be considered history. There are clear overlaps between the two, but I think many of us still have problems reconciling them. Fact and fiction are actually complementary entities, and if we read them alongside each other, we might be able to arrive at a better understanding of history as a whole.

WRITING INTUITIVE AND EMOTIONAL HISTORIES

LB: If I publish a book, say, on a Burmese photographer, I am of course engaged in the act of writing history. Yet, I don’t like the idea of writing history per se. I prefer the idea of telling or transmitting stories. I know I’m writing history, but that notion still makes me uncomfortable. That’s why I’ve been using material from history books to piece together something completely different — a more intuitive or emotional history. By using the same materials in different forms, it proves that there isn’t just one narrative, and there is never just one narrative. I’m always more interested in the personal story — be it the story of the photographer or the photographer’s clientele. These stories form the backbone of my own research.

If you look at a photograph, one would be able to get a sense of the big picture quite immediately most of the time. By taking the personal story, instead, as a starting point, a very different understanding of society is created. When communicating history to a wider audience, I find that personal stories are always more effective tools as compared to facts or statistics. Yet this is not to say that the personal story is detached from facts and statistics. A personal story always leads you back to the macro scale of the socio-political climate of the time.

I’ve conducted interviews with Burmese photographers, and have asked them why the photographs they made were so small in size. The conversation would turn towards the fact that it was hard to get the necessary materials for photography. Why was that the case? It was because a ban was in place, and the ban was a result of sanctions placed onto Myanmar by other countries. These sanctions were a response to the actions of the ruling military regime. So how did the photographer get any of these materials at all? They were illegally imported. From this simple line of questioning, you can see how I managed to connect one photographer’s own experience seamlessly to the structural realities of economic trade at the time.