Mary Bernadette Lee is an artist, educator, and illustrator. Her practice takes the phenomenological approach investigating relationships between body, architecture and space, and psychological states. Her works include paintings, illustrations, linocut prints, monoprint prints, woodcut prints, clay sculptures, textile installation, and publication. She collects people’s experiences through collaborations and artist-led programmes, and examines relationships in relation to Self, Identity, Community and Home.

As someone who wears multiple hats, Mary’s work epitomises a synergistic relationship between artistic creation and giving back. Most recently, she exhibited A Bout of Nostalgia at The Substation, where she collected childhood memorabilia (or chou chous) from willing participants to create a compelling and moving installation. For this feature, Mary picked out two books — one by Gaston Bachelard and another by John Berger — and the first clay sculpture she ever made.

As someone who wears multiple hats, Mary’s work epitomises a synergistic relationship between artistic creation and giving back. Most recently, she exhibited A Bout of Nostalgia at The Substation, where she collected childhood memorabilia (or chou chous) from willing participants to create a compelling and moving installation. For this feature, Mary picked out two books — one by Gaston Bachelard and another by John Berger — and the first clay sculpture she ever made.

¹ The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard

I wanted to open our conversation with your selection of Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. He was interested in how we navigate spaces, and his ideas have influenced a whole wave of practising architects. In that, I saw similarities to how you’ve described your work. You’ve been interested in how we relate to spaces, and this shows in how you articulate your practice. What do you like about the architectural language, and how does this vocabulary do in help define what you do?

Bachelard has a way with language, and this allows the reader to almost move through these spaces within one’s own mind. It’s not about being technical, but he describes things in great detail. His writing would give prominence to the speckled pattern on glasses or the grain of the wood. He personifies these spaces. This creates a warmth about his writing, and allowed me to move into the body of these spaces he writes about.

I haven’t read many books on architecture, but I find myself coming back to The Poetics of Space time and time again. I picked this book up whilst I was in my final year at the Nanyang Technological University’s School of Art, Design and Media. I was doing a project where I documented old architectural buildings in Singapore that the everyday pedestrian might just walk past and not give second thought to. Singapore is overcrowded with futuristic buildings that create the commotion of spectacle. As a result of this, other buildings can fade into the background. By drawing a contrast between “old” and “new” Singapore, I wanted to question what the future of Singapore could look like. I did an open call, where I asked the public to sketch out how they imagine Singapore to be fifty or a hundred years from now. I collected close to 30 sketches, and compiled them into a zine. It was so interesting to see how people of different ages and backgrounds approached this question. For example, my father’s perception of Singapore in the future included buildings that looked like stacked blocks. On the other hand, I had the sketch of a child where his idea of the future was one where there would be a lot of linkways. We always see the future in relation to what we know, what we’re exposed to and our own personal preferences.

The experience Bachelard describes is similar to how we relate to each other as human beings. In order to get into the mind of another person, we need to meet and have conversations with them.

There is a softness around these sort encounters, and what I’ve found with architectural language is that it has this capacity for expansiveness. It’s limitless, and that’s what my approach to art is.

I try not to limit myself or the people I work with. When you keep things as open as possible, you begin to see all these possibilities. In the midst of all of these possibilities, you realise how simple things truly can be without losing that feeling of expansiveness. This is something Bachelard discusses in his book as well: in miniaturising spaces, we actually open them up.

In light of this expansiveness, it’s also important to note that you don’t limit yourself to a single medium. You work in painting, drawing, installations, sculpture, and prints — just to name a few. I appreciate the limitless nature of the language you use, but do you find that this has been limiting in any sense? For example without clear categories or labels, that lack of structure can also be seen as a barrier to engaging audiences in the full richness or complexity of one’s practice.

To be honest, I felt a little conflicted two years ago. I’m always thinking about how I can define myself and my role. I often wonder if I should specialise in one particular medium or continue dabbling in different mediums. I don’t have the answer to that question, but in a sense, I think what I’ve done so far has telling. I just let my heart lead the way. Whenever a particular medium interests me and I see possibilities in using it, I get incredibly excited. I see branches of expanding possibilities, and how that can be applied to a particular body of work or a series of workshops I’m conducting. I’ve made peace with who I am in more recent years. I like playing with different things, and how the various mediums inform each other. I enjoy how the medium can become the message, and the message can become the medium. I find that everything is interdependent and inter-related. You can’t isolate one thing from another, and I do like where I am right now with my practice. I’ve moved away from more traditional methods of making, and have begun to incorporate objects into my works. In the exhibition I put up at The Substation, A Bout of Nostalgia, I found myself moving away from creating a work that’s my own and towards creating a body of work that is based on the experiences of others.

I’ve been collecting the experiences of people for a long time. I worked on an installation for the Esplanade Tunnel titled I See You See Me in 2015. I wanted to examine how people see themselves, and so I collected self portraits from others for this work. I was fresh out of school and rather self indulgent. I was interested in creative narratives and telling stories about the way in which I see the world, with hopes that this could help build on the viewer’s own perspective of the world around them. I think the world needs more of that.

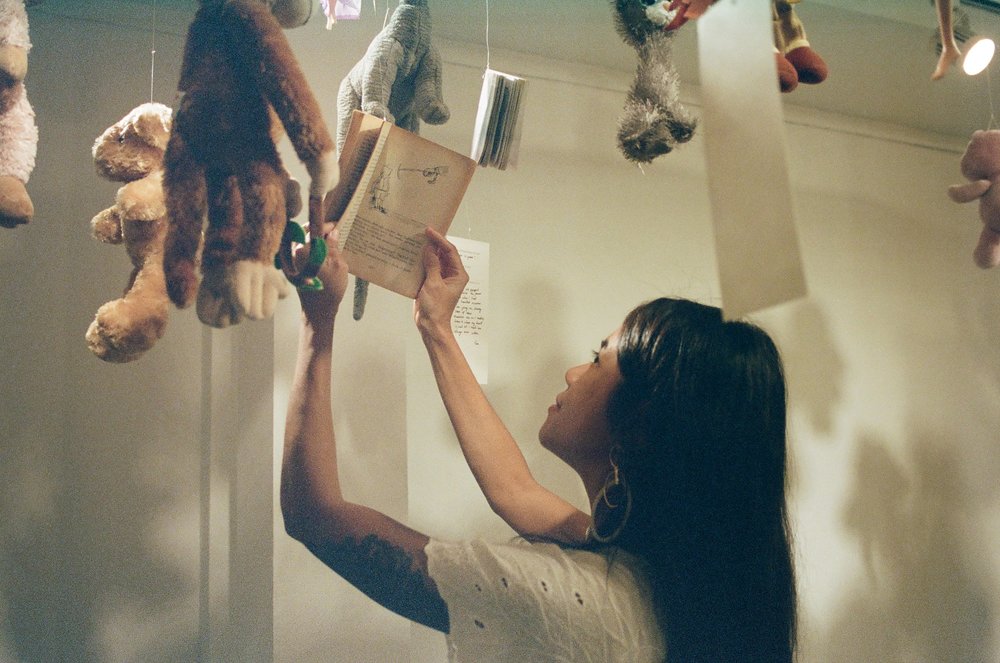

² A Bout of Nostalgia, Mary Bernadette Lee

2019, Installation View at The Substation

2019, Installation View at The Substation

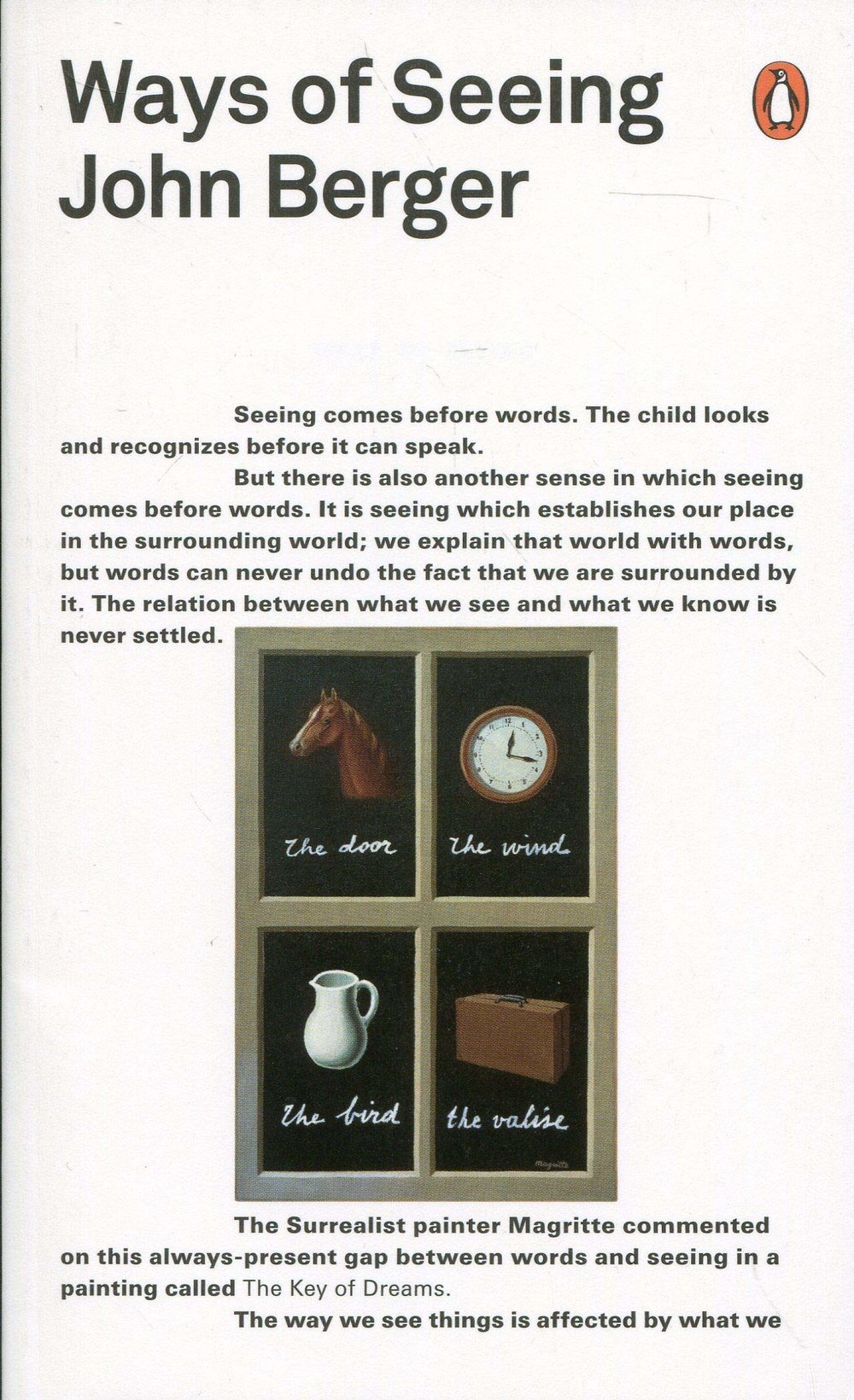

³ Ways of Seeing, John Berger

This leads quite nicely into John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, which is another book you picked out for our chat. Berger drew a continuity from the historical up to the present day as to the ways in which we look at art and images. Having worked in the creative scene for awhile and across various mediums, how do you see the relationship between the mediums you use developing? Do you think these thoughts have been translated into how you now frame or present your art to audiences?

I do think about the hierarchy of images and objects in relation to the message I’m trying to get across. If I’m working with a community and the message is about them, I think it is important that the work is created by them as well. In those instances, my role is that of a facilitator’s. I help ease them into spaces where they feel safe to express themselves freely and creatively. As a facilitator, a large part of what I do includes helping these participants see that the work they create does not have to be literal. For instance if they’d like to create an artwork about home, they do not have to depict a house. It could take the form of a cocoon, and that could be representational of a home. It is very much about visual literacy, and helping my participants grow in their understanding of symbolism and representation.

I always take who I’m working with and who my audiences are into consideration. For me, it is important that my works are relatable and accessible. My approach to art making is usually quite playful and experimental. I want to create works that are experiential because I find that viewers are most perceptive to such works.

One medium might not know more than the other, and each one is different. The question then is how can they complement each other?

This reciprocal relationship is something that I’ve been exploring both in my work and in how I relate to the communities I work with.

Why is that accessibility important to you?

I believe that art has to serve a purpose in order for it to work. Even with an object as simple as a vase, if one looks at it and finds it beautiful, it would have served a function. I also see art as a way of educating people outside the four-walled classroom environment.

Throughout my practice, I’ve come to understand that people seek out personal connections. Not everyone is interested in academic or intellectual discussion. What is personal often comes in the form of things such as colloquial language, for example, and viewers do resonate with that.

This point of view was solidified after I completed I See You See Me at the Esplanade Tunnel. I got a lot of positive feedback about that exhibition, and viewers were telling me about how much they enjoyed looking at these works and the descriptions that accompanied them. Although the drawings collected were done by individuals from varying backgrounds and capacities, they all reflect a certain childlike disposition. From there, it became clear to me that everyone has a child within them and this childlike wonder just needs to be ignited.

⁴ I See You See Me, Mary Bernadette Lee

2015, Installation View at the Esplanade Tunnel

2015, Installation View at the Esplanade Tunnel

You have quite an intimate, personal relationship with those who view your works and share these thoughts with you. Would it be fair to say that these responses are a significant aspect of the works you create and showcase, and that the work continues to live on within these collected responses, even after it has been deinstalled from the exhibition space?

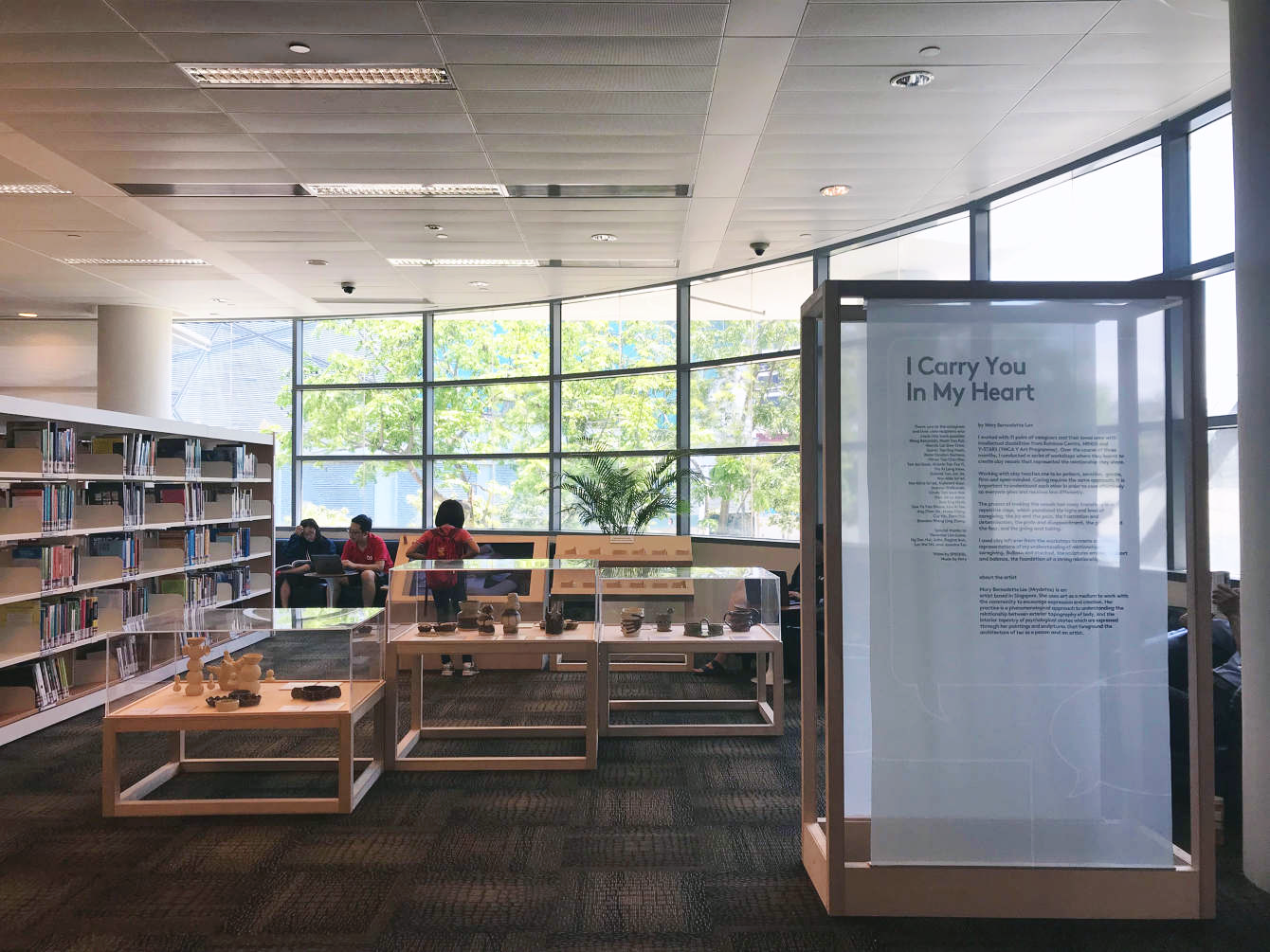

With I Carry You In My Heart, a project I did with Personally Speaking, I wanted to place the clay sculptures created on display stands that would come up to the level of the viewer’s thigh. This would invite viewers to bend down, kneel down or even squat when viewing these works. The works shown were done in collaboration with 11 pairs of caregivers and their care recipients, and I think there is a lot of misconception around what caregiving for children with autism means. I wanted viewers to engage with these stories, and so I displayed the participants’ sketchbooks along with the completed clay works as well. Alone, the clay vessels can seem rather abstract. But if you follow the participants’ journey through their sketches, you get a better glimpse into their creative process. I see a person as a house with many rooms. Some of these doors are closed, and others are opened. If we choose to open up one of these doors, we invite someone else to come inside and to look at what lies within us. In a way, I also see the house as a metaphor for one’s body. By framing these clay vessels through written texts, videos and sketchbooks, I wanted to make sure that viewers were eased into occupying these spaces and empathising with the stories that were being shared.

I worked with three different groups for this project. One group was from MINDS, another from the Rainbow Centre and the last was from YMCA. Through my participants, I came to understand how caregiving is truly a round-the-clock affair and an entire family is often involved. To me, caring is about this support system. At the end of the project, I created sculptures in response to the sculptures the caregivers and their loved ones made. I collected the clay pieces that were leftover at the end of every session, and I wedged them back together again. I used these pieces to create bulbous, stacked clay vessels that were well balanced. I think of this act of collecting and sculpting as a caregiver reminiscing over the day’s happenings and decompressing.

For this project, I wanted to use clay because the way one treats clay bears a lot of similarities to how one would handle a relationship. Clay comes in different varieties such as porcelain, raku or terracotta. As humans, we all have different personalities too. You also have to figure out how much pressure to apply onto the clay and how much water to add to it. The act of caring is very similar. The amount of love you shower onto a child is tempered by the fact that sometimes you have to take a step back and allow the child to learn independence. Clay vessels can be collapsed and reshaped as many times as you like. In a relationship, you get these similar motions of growing and collapsing as well. When you feel comfortable enough with what you have, you glaze the object and fire it. Yet even so, it isn’t a state of permanence and it can break if one drops the object. You can put the broken pieces together again with processes such as kintsugi, and therein lies a parallel to how we relate to one another as well.

One of the participants in the project wanted to break the clay sculpture after it was fired. Even though I could see where he was coming from, I asked him why he wanted to do that. I wanted him to own this idea as his own, and this is what I want for all of my workshop participants as well. His response was that he knew that both his daughter and his relationship with her was not perfect. He wanted to show that with a vessel that was cracked, and to link that to himself with a bridge of love. I watched him as he glued the cracked pieces together, and it was marvelous seeing him show the piece to his daughter, Grace. He showed it to her and said, “Look, this is what we made together”.

These projects are very humbling for me, and they allow me to step into spaces of great healing.

⁵ I Carry You In My Heart, Mary Bernadette Lee

2018, Installation View at Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film

⁶ I Carry You In My Heart, Mary Bernadette Lee

2018, Installation View at Jurong Regional Library

2018, Installation View at Objectifs Centre for Photography and Film

⁶ I Carry You In My Heart, Mary Bernadette Lee

2018, Installation View at Jurong Regional Library

This particular project with Personally Speaking took place over a six-month period. When you say that you work closely with communities, audiences might not get the sense of time that passes between each session or the sort of legwork that goes into preparing for these workshops. Could you take me through the whole entire process of how you would approach these projects?

I always approach these projects with the mindset of wanting to know my subjects. The creative aspect of it comes much later. It always begin with me trying to build a relationship with them and establishing that sense of trust. During this period of time, it is also important for me to establish my intentions. I do not see them as working for me, and I’m very careful with that because that’s both ethically and morally wrong. Instead, I frame these sessions as a mode of expression and some of these lessons can be transposed into the context of the home as well.

For this particular project, I wanted to really understand the relationship between the caregiver and the care recipient so I visited them in their homes. I always set up what the expectations are at the beginning of the project, and so if the participants agree to being involved, I know that they’re ready and open to this experience. In turn, I spend time with them and it could be as simple as chit chatting in their homes about their everyday routines. Throughout this process, I’m constantly making notes about what each child needs. Some children are non-verbal, others are sensitive to noises, and some can get quite violent at times. My approach to working with the caregiver and the child in a group setting will be informed by these notes. For example, one child in my group workshop loves playing with water. I’d give her a pan of water to play around with, and that gets her engaged. When she’s engaged, she was more likely to learn how to add water to clay. There is a lot of trial and error involved, and it is sometimes only after weeks of engaging with the child that I learn what helps them learn best. It is about discovering where their interest lies, and all of this takes time. Eventually, I found myself in a similar position where I was caring — not just for the children, but for the caregivers themselves as well. I wanted to make sure that everyone was comfortable, despite being in a foreign space. It was tiring, frankly. I cannot even begin to imagine how tiring it must be for these caregivers.

We started with the basics before we even went into ideation processes. I taught they how to treat the clay, and three different hand-building methods — pinching, slabbing and coiling. Once they were comfortable with the clay, I told them that they could use a single technique or a combination of them to create their eventual vessel. Every time the participants completed a vessel, be it a cup or a bowl, I’d tell them to collapse it. I didn’t want them to get too attached to the first instance of success and to get used to repeating these steps instead. At the end of every session, I would lead the participants through some reflections. For example, I’d ask them to describe their caregiving relationship in one word. I wanted to make the entire process as smooth as possible, so it was a gradual progression from words to mind mapping, from mind mapping to lines, and then from lines to shapes. I’d then ask the participants to see if they could craft a vessel based on these shapes. At the end of the day, the idea has to come from them. My role is to function as a sounding board for them to clarify their thoughts or intentions. Before they even start on a prototype of their sculpture, the whole process would have already taken three to four weeks.

⁷ I Carry You In My Heart, Mary Bernadette Lee

2018

⁸ I Carry You In My Heart, Mary Bernadette Lee

2018, Installation View at Community Plaza, Oasis Terraces

2018

⁸ I Carry You In My Heart, Mary Bernadette Lee

2018, Installation View at Community Plaza, Oasis Terraces

Coming back to the bulbous sculptures you created in response to the participants’ works and their stories, was there a particular event or happening that triggered or necessitated that response?

Initially, I didn’t want to include myself in the exhibition at all. Throughout the six month period, I saw so much care — not just between the caregivers and their loved ones, but between the caregivers as well, through acts as simple as bringing biscuits or snacks for each other. I realised how important this support is, and I wanted to visualise that. That’s why I started collecting the leftover pieces of clay for my response piece.

⁹ [Untitled], Mary Bernadette Lee

2015

2015

I noticed that the female figure features quite prominently within your work as well. Womanhood is an experience that means different things to different women. Other than obvious personal connections, is there something particular that draws you towards tapping on images of the feminine and womanhood?

When I first used the female figure in my work, I was approaching it with the intention of self exploration. I wanted to unravel the nuances that underlie how a woman occupies space, be it poetic or political. I realised that how I carry myself differs depending on the sort of space I find myself in. There are certain rooms that I feel repulsed by, other rooms that I feel powerful in inhabiting and even some that I feel unsafe in. I wanted to understand the architecture of myself, and get to the bottom of why I felt the way I did.

These explorations soon developed. Instead of examining how I related to physical spaces, I was also interested in internal and mental spaces. These were imagined landscapes, but I found myself still gravitating to the image of the female.

Berger’s Ways of Seeing also touches on how we look at women and their bodies. As someone who is both the surveyor and the surveyed, his writings helped clarify my understanding of my own body and how I carry myself. When I speak of how I carry myself, I don’t mean how I move through spaces. I’m talking about how I think and how my attitude has evolved.

All of this informs how I see the nude, or the naked.

I see nakedness as a vulnerability. Nude is how we see things — a portrait of a nude woman or a nude sculpture bust. On the other hand, nakedness is a state of being — a person is naked.

As time passed, I began keeping these drawings to myself instead of actively showcasing them. There is a trend now of capitalising on the nude, female figure. You see naked women on tote bags, t shirts and all sorts of paraphernalia. Vulnerability, as presented by capitalism, has been reduced. This pushed me to think about how I could present vulnerability in other forms. I started dabbling in clay, drawings, and using a combination of mediums.

I think I’m coming back to the female figure now, albeit in a very different way. I’m doing some illustrations for a publication, and the book is narrated from a woman’s perspective. I want to show the world through her eyes, and I want to be intentional in how I approach this. It’s not so much “I am woman, hear me roar” as it is “I am woman, hear me speak”. It no longer is a fight for independence, but a quiet voice of hope for the future. In and of itself, I find that quiet confidence vulnerable.

As someone that works intersectionally, how do you understand the relationship between what you produce as an artist and what you produce as an art educator? Do you see them as balancing each other out?

Having dabbled in different mediums with a diverse practice, I would say that what I produce complements each other. Being an artist is a medium, and being an art educator is a medium. Different roles inform each other, and I’m interested in seeing how they can help strengthen my perspective on the other. The art educator in me will remind the artist in me to temper my creative indulgence with a firm grasp of reality and my desire to create an impact on the lives of others. On the other hand, the artist in me will show the art educator in me different ways in which I can help participants relate to my lessons better.

When creating art, beauty is not always important. To me, what’s important is the heart that goes into the work and how one deal with the stories that have been entrusted to them. It is a position of responsibility, and I treat every story I collect with respect. All these different facets of me are always in conversation with each other, and as such, they complement each other. It comes back to the metaphor I used earlier of a person being like a house with many rooms. I can always open up new doors and possibilities, and that is both colourful and exciting all at once.