Mike HJ Chang is a Taiwanese American artist and educator in visual arts. He works in variety of medium including sculpture, installation, and drawing. Recently he has been focused on watercolor painting as a way to understand how to use color. His interests include convention of sight, elasticity of motifs, cartoony interpretation of realities. Cartoony because, he wants to articulate a space between sensuous and sloppiness but rather inadequately and somehow convinced that is okay too.

We sit down with the artist in his studio on a rainy afternoon to talk about some of the films, paintings, and drawings that he’s been drawn to over the years. The range of materials Mike picked out reflect the explorative nature of his practice, having worked in various mediums over the years. Over the course of our chat, we manage to touch on the artist’s ideas of sight and seeing, his thoughts on teaching and the enduring quality of humour in his practice.

We sit down with the artist in his studio on a rainy afternoon to talk about some of the films, paintings, and drawings that he’s been drawn to over the years. The range of materials Mike picked out reflect the explorative nature of his practice, having worked in various mediums over the years. Over the course of our chat, we manage to touch on the artist’s ideas of sight and seeing, his thoughts on teaching and the enduring quality of humour in his practice.

¹ Dance Of A Humble Atheist, Toh Hun Ping

2019

Let's start off with your selection of this experimental clay animation, Toh Hun Ping’s Dance of a Humble Atheist. In this work, there is a conveyed momentum and fluidity, as in its title of “Dance”, contrasted against the rigidity and fixedness of the material clay, and the choppiness of stop-motion. What do you like about this animation, and what do you make of these interplaying and seemingly contrasting factors?

It is certainly interesting to have these two qualities that don't seem to fit together. I am particularly drawn to this work because I feel that there's a lack of experimental animations in the fine arts scene here. There are not many fine art artists making experimental film; it's a very small community. I think what's most impressive about Hun Ping's work is that he is able to take a very traditional, craft-based medium of ceramic, apply it through the lens of experimental film, and create a work that is so trippy and alien. One can get so ungrounded looking at these images, and get lost in the sense of scale and depth. It feels both like standing on a foreign planet, and like looking at something through a microscope. The sense of scale keeps shifting very dramatically. I just think the work is very successful being both nuanced and aggressive.

I would like to see more and do more experimental animation. I guess in Singapore, a lot of animators are a lot more computer based. There are a lot of animators trained here, but often for entertainment purposes, like making computer games. It would be great to see more experimental stuff. Animation is a great storytelling device, and I think there's a lot of room to grow.

Your work often ruminates on the broader themes of sight and seeing — who is seeing, what is being seen, how seeing relates the seer to the seen. In Blue Trees, Black Fruits, you begun with asking if it was possible to see the world nakedly. Where now do you stand with this question?

I think the word “naked" is somewhat poetic. Sometimes I start a project thinking about a few words, which have a depth that can be dug into. “Naked" as a word has a lot of potential. It doesn't have to be understood just literally, but can also be metaphorical or figurative; it doesn't have to be about the human form, but can also refer to objects.

The way we see things are based on conventions, lenses, perspectives. All of those things are in between you and the object you are looking at.

I began with thinking about how the act of seeing is actually trained behaviour. We learn how to look. We learn what to look.

We learn what is nonsense, what is beautiful, what is ugly. These are learned, and not natural. Because I make pictures, this is something I think about a lot. I want to carefully consider and to address what is seeing and sight, how that affects the image I make and how they are seen.

To see things “nakedly" is one way of seeing. I am imagining what it would be like if I could remove the lenses, the perspectives, the language, and the history. Of course, this is impossible, but it got me thinking — if we do remove all these things, maybe comprehension then becomes impossible. It's like directly staring into the sun — that's is not good for you. Perhaps we have all these devices and learned behaviours in place because we are trying to protect ourselves from overexposing, overbearing. I imagine a world where maybe we can remove all that for one second, and I make something to illustrate that second; from there we can understand the importance of the layers.

When I am drawing, it's really about adding and removing layers. Sometimes I add, sometimes I remove. Once we can navigate between the layers, we can either see their importance, or judge whether they are necessary.

² Blue Trees, Black Fruits, Mike HJ Chang

2019 — ongoing

2019 — ongoing

That really reminds me of Plato's allegory of the cave, which you've also mentioned as a reference point in your work before.

I imagine for each of us a second interior, where we process, interpret and understand life.

That is, in a way, a nice analogy to photography. We need a dark space for light to be exposed on the film, and we need a dark chamber to process the image. In some way it's also a nice metaphor for art-making. Art studios are like pockets in that chamber. If you only live in the outside, being exposed to everything, it's difficult to frame your ideas, find your footing. Having that studio or interior space is a way for us to slow things down, and to find a framing, so as to speak.

2018

2019

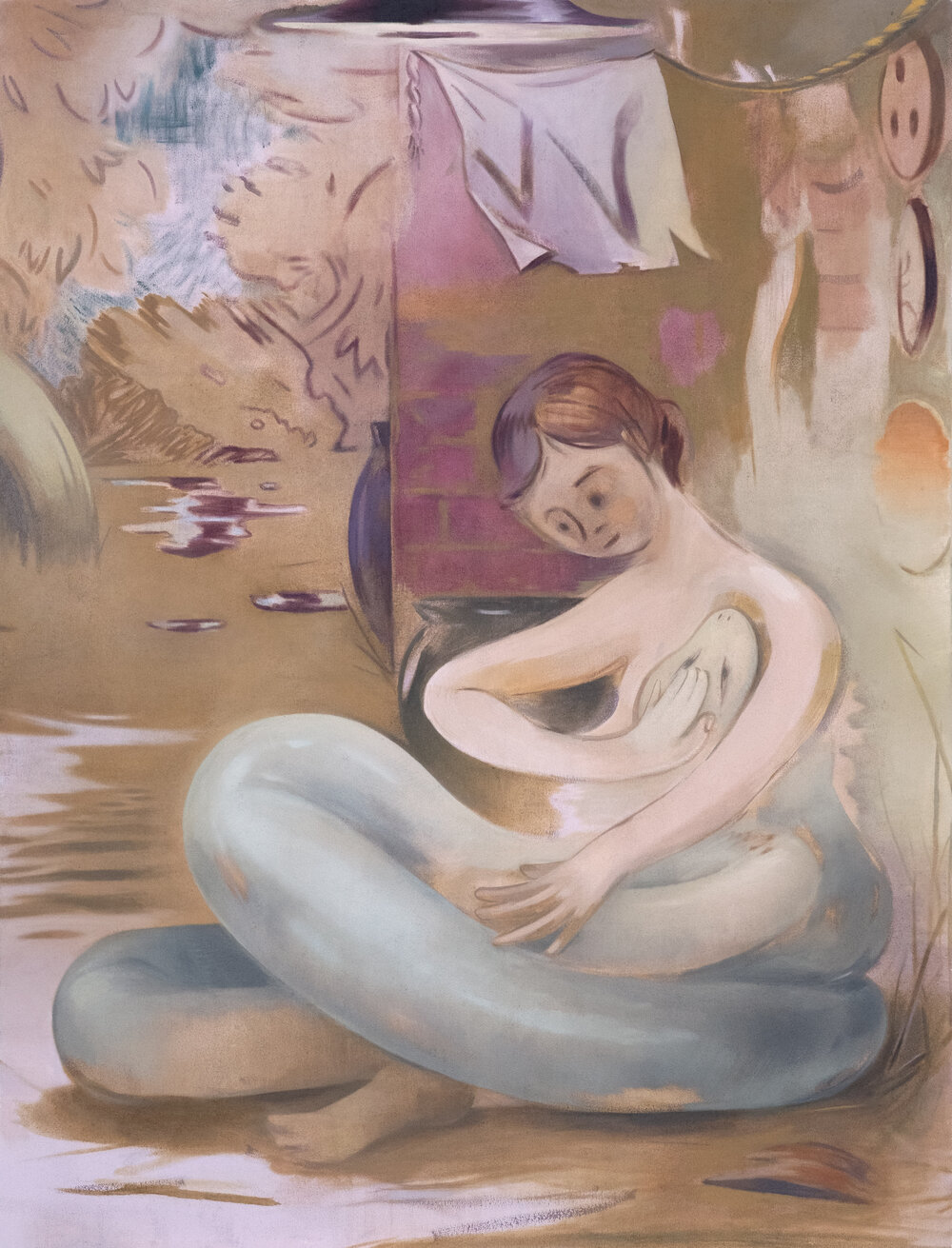

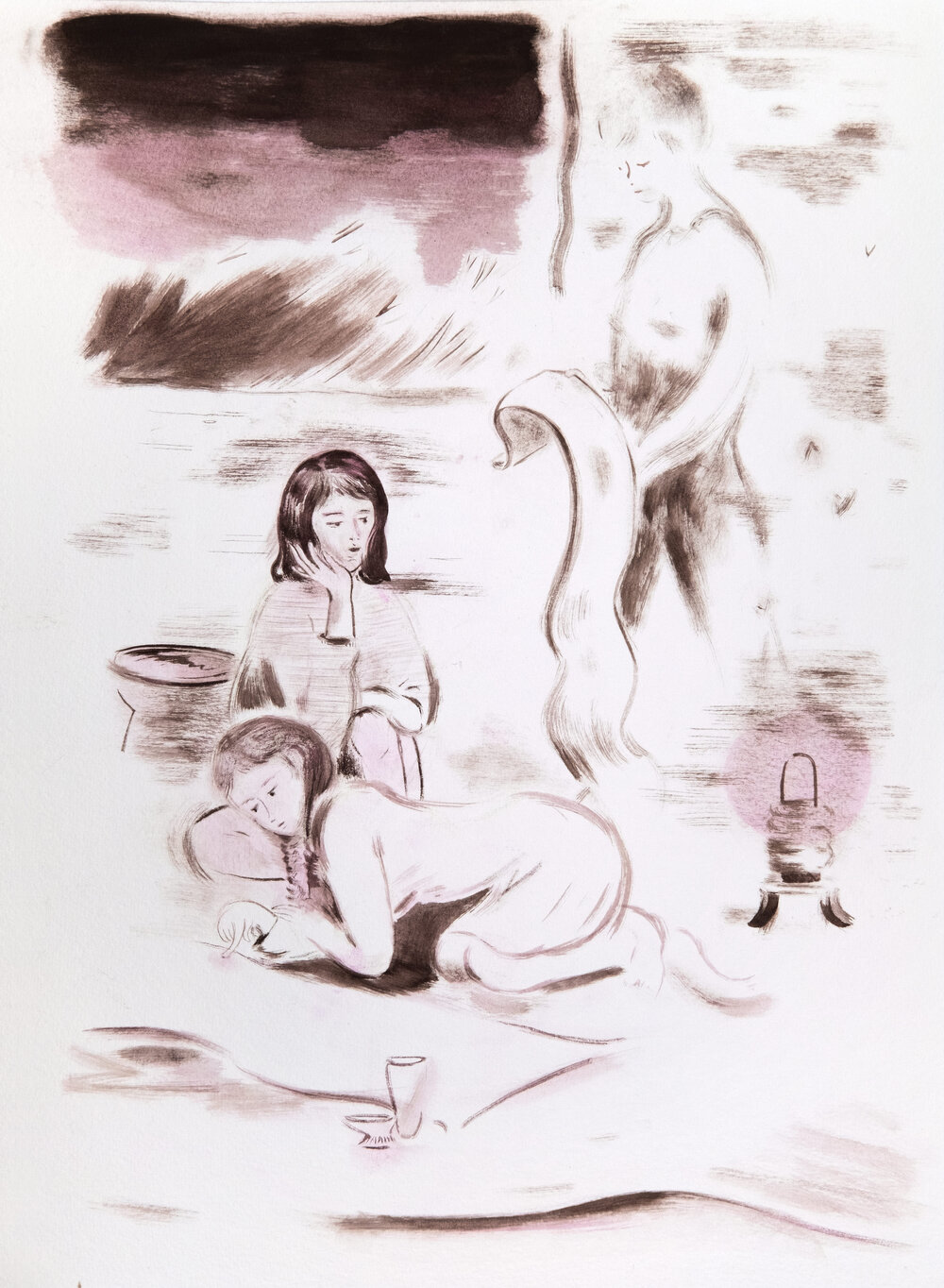

For your selection, you picked out the works of artist Juka Araikawa. You have worked with Araikawa for a long time and have also exhibited together. You will also be collaborating on a two-person painting exhibition that opens next year. Having worked with her across different mediums, you nevertheless referred to Araikawa as one of your favourite painters till today. Can you expand on why her paintings intrigue you?

There are some people that I feel like are natural painters. Some people can draw or paint with a special quality. I think that quality cannot be learned; I don't think I have it. But I can feel it in other people that I come across. Sometimes I see students that I teach, who have that intrinsic, special sense of touch. I think Juka is one of the rare people that have that innate sense of touch, and way of looking at things. I like her works a lot because I don't think I can do what she does.

There's a sense of ghostly poetry to the way she paints and draws. It's very hard to describe with language. There are also others who have a special sense of configuration, composition, mark-making, or colour; these to me are very unique, and they are unique because it's very hard to describe. Once you see it, you will know. But it's very hard to go look for it.

I think it is especially ghost-like, because it's hard to capture with language. Most of us think through language, but her paintings have this sense of divorce from language which I really appreciate. It's both familiar and unfamiliar. There's a bit of comedy too, which is not obvious. I like this nuanced quality in art. She really pays attention to every little mark she makes. I on the other hand don't do that. There are very subtle things that she does on paper, that are very articulate, very precise, but the reading of it is very open. There's a certain lightness to it that I really appreciate. All these things come together to make her paintings very enjoyable for me.

I guess every artist has a different kind of affect that they want to project onto the audience. Some artists are very good at making something very heavy, which makes you feel overburdened, overwhelmed, emotionally strained. But for Juka, the affect is so light, it can almost not be there, like a ghost.

Through your description, it seems that both your works are rather different. How has the different qualities of your practice translated into your collaborative works?

Even though we studied together and have worked together for quite a while, in terms of art-making we have quite different sensibilities. She almost never uses colour now, but I use all the colours I can find. We make rather different images, produce quite different things, but there are certain qualities that overlap. For example we are quite similar in our humour being never being over-the-top, and in preferring nuance. When working towards curating our show together it's about how one work can bring out more in the other work. I hope that our works, together, can bring our more nuanced qualities.

The sense of humour in your work is something that also jumped out at me, especially looking at Cinema Surrogate #2 and Cinema Surrogate #3. That was incredibly fun.

That's the soda cup and the bird?

Yes!

I plan to make a lot of them. I don't think Juka would ever make that kind of works, these are more my sense of humour.

The Cinema Surrogates kind of go back to Plato's Cave — I imagine cinema space as another metaphor for a dark cave — there's a gigantic screen, we sit there and understand stories. Instead of having actual audience in a cinema, I imagined what it would be like if we just sent a surrogate to watch the movie for us. Since we already bootleg movies, I also had this idea of imagining what it would look like if we could bootleg reality, and what such a surrogate would look like.

Cinema Surrogate #2 is shaped like a soda cup so that it can fit into the soda cup holder, to be very still. Cinema Surrogate #3, the bird, I'm not sure where it came from. Some of these are very random, I really don't remember.

I really like a little bit of randomness. I think a lot of artists are very conscientious about the decisions they make — with their research, with what kind of colours and what is the appropriate form to carry their idea. Sometimes, I think randomness can be quite interesting as well, and comedy can come from letting go of logic a little. Sometimes when I draw, the sillier they are the better they are. It's weird for me, because I also don't believe in pure randomness.

I think about order and chaos a lot. I believe I would like my art to be on the edge of complete chaos, but just one step back, so there is a slight sense of order. If you take one step over you would find complete randomness, but I want my work to be one step away from that. I think the bird is probably somewhere around there. That's the zone I'd like my art to occupy, just one step away. To some people it might be complete gibberish, but to me there are some rules that I follow while making it, as much as these rules are hidden to the viewers. They must look repeatedly to find out what kind of logic underlies it. I find it interesting to examine what is order and what is chaos.

⁵ Cinema Surrogate #2, Mike HJ Chang

2016

⁶ Cinema Surrogate #3, Mike HJ Chang

2018

2016

⁶ Cinema Surrogate #3, Mike HJ Chang

2018

⁷ Demons, Daniel Hui

2018

2018

And on that note about chaos, another work in your selection — Daniel Hui's Demons — is an intriguing film which many have struggled to find the adequate words or terms to fully describe. Tell us about how you encountered this film, and what about it stays with you until today.

Daniel is a friend, and I helped a little bit with the film, working on props. I saw it recently at The Projector. I think Daniel intended for it to be a very personal film, specifically addressing depression and what it looks like for people involved in the arts scene. The characters are an actress and a director - and that relationship is very personal to him. I'm not a filmmaker, or actor, or director, but the metaphors in the film can be applied to various other relationships. I especially linger on the idea of who is consuming who, and who is taking over. There are certain power structures in that relationship.

What I am most drawn to about the film is how funny it is. I was definitely the one laughing the loudest in the theatre. It is a very serious film and I don't think everyone found it super funny, but there are a lot of scenes in there that really underline the fact that comedy and tragedy are tightly bound together. When things are too tragic they are also funny, and vice versa. That's one powerful thing about art — art is a place where you can mediate all these emotions. You can laugh at things that are tragic, and you can be sad about things that are way too funny. It's hard to do that in reality. It's kind of what I feel about US politics as well — it's too funny, too sad, and too painful to think about. But good art becomes a place onto which audiences can project their feelings, and they are then able to articulate these emotions. We can laugh at it; we can hold it very close to our hearts and feel like we want to cry. I think the film did a very good job finding a middle ground between these two aspects.

I guess a lot of times I do think about these dualities — order and chaos, tragedy and comedy. To me these binaries can be a bit unproductive, because I don't think the world is made up of binaries. There needs to be another dimension. So instead of drawing a straight line between two things, I think there can be a triangle, or a graph, which would look quite different. With that, when you think about things, you can be more open or imaginative. This is something that I haven't really figured out.

Your work often deals in drawing relationships between two points of what people think might be a binary. What interests me is how you describe relationships — for instance between eye and hand, or sight and reality — through the artistic process of transforming ordinary observations into depicted forms via documentation. Through projects such as Enlarged Nerves and The Retrograde, which come in the format of documentative sketches and drawings, how has the way you look at documentation as a process changed? Is there a translation, or a gain or loss, between each step?

The more sketches you have, the more a visual language emerges. As an artist, what I'm essentially trying to do is to build a language through sketches and notes.

I feel like it's important for me to document the process because I have a bad memory.

I need to constantly remind myself why I am looking at particular things. Sometimes I don't know why, for example, I keep staring at a park bench, so I have to repeatedly question what draws me to this object. By drawing pictures, doing collages, I can figure out why I'm obsessing over a particular thing. These processes can be very messy, or can go on in loops that go on forever. These projects are then my way of articulating or editing by putting things together.

Before I did this, I used to just put everything up on the wall, to try to figure out how I can put together certain images. I realised that I ended up with way too many images, and I needed to edit. For me, editing means to take away, to subtract, to come back to the core. Sometimes when you make too many images you kind of forget what's in front of you, and by editing you can rediscover the central question you were asking at the beginning. Sometimes that question can shift. When you edit you figure out what things are really possible.

This is a process of expanding and contracting, expanding and contracting. I do that multiple times within one project, and it can be random, which is good. It's about finding a system to produce images - that to me is a nice way to describe artistic practices. My practice doesn't really involve research of current events or history in a particular sense; I research to figure out how one creates a system to produce. That's what I'm interested in within other people's work as well - what is the system in their work which is hidden from me? What are they withholding from me? I of course also hide things from my viewers, because the behind-the-scenes is not so interesting. It's just like when you look at a car, you don't really need to see the mechanisms behind it. I guess in Juka's work or Burchfield's work I feel that I can see, from work to work, that hidden system they have in place to produce those images. I'm interested in those things, and in my own work I'm also interested in these systems of input and output.

⁸ The Four Seasons, Charles Burchfield

Krannert Art Museum, 1949–1960

Perhaps could you expand on what system of production or work that you've found in Burchfield? His practice is especially quite different in that he was committed to watercolour painting throughout his career, whereas contemporary artists now, including yourself, rarely work in just one medium. How does that inform your practice?

One of the things I'm quite bad about is that I don't really read up about other artists. I did however drive four hours to see his work in Buffalo, New York, because I felt that his paintings are just so great. I don't know much about the man, and I don't know the way he works. I prefer to figure that out on my own, by looking at the works - that to me is enough to understand how he approaches painting.

Burchfield actually designed wallpapers first and didn't start painting until he was much older. He just painted landscapes, and only in watercolours! He paints very common things — trees, houses, the weather, the forest, fire. His motifs are really basic, with a rustic and rural feeling, which I appreciate. I lived in America for a long time, and through his paintings, I get a vivid sense of how it's like to be in upstate New York or Buffalo in the 60s and 70s. I'm particularly drawn to how he uses colour. I can't say anyone else has his colour palette. He uses this lime yellow, which fascinates me, as personally I don't really use yellow because I can't figure out where to use it. The way he uses yellow for light is really poetic and very beautiful. I feel like he's figured out a way to describe light in particular ways - the light going through a forest, in a thunderstorm, just after the rain, or just after sunset. The quality of his light is very interesting. These are neither realistic nor impressionistic portrayals of light, but a very different approach.

What is also interesting about Burchfield is that he paints really boring subjects, but the paintings are really psychedelic and crazy. The way he paints flowers and trees make me wonder if he was on drugs — yet he seems like such a typical American old man living in Buffalo. The way he makes images is quite amazing. Before encountering his work I had no idea you could use watercolour this way. Anyone who paints knows there are typical ways to use colour, to describe objects. Burchfield just threw all of that out of the window and completely did his own thing. His paintings look a lot more like oil paintings than watercolours.

For me, that was a point of inspiration because I realised I didn't need to paint in particular ways, or to learn to paint properly by watching tutorials. So I just learned to paint my own way. I don't think I'm anywhere near good yet, but once you've thrown out tradition there's a lot of space to explore.

In contemporary art, it does seem like fewer and fewer artists are sticking to one thing, I myself included. I feel that there's both a need and a sense of confidence that we can make work based on the idea. I do think that a lot of artists today work first on ideas, which they then apply the form to. A lot of artists like to be flexible in terms of what material they use, and I think that's what I've also done for a long time. I might change the medium based on the needs of the idea. For painting, however, a lot of times the idea is secondary. To be a painter, the fundamentals lie in the way you work with the material: composition, colours, brushstrokes. All those things, to me, are more important than what the painting is trying to describe or say. Sometimes I enjoy working on painting because I don't need to figure out what the message of the artwork is immediately, but can slowly articulate that as I paint. That, for me, is becoming a more natural way to work.

Sometimes, for example with the Cinema Surrogate project, I start with a very specific idea. Those works are idea-based and I can use any medium that I like. When I'm doing painting or drawing, it's instead more about the material. These are two very different practices, and I enjoy both. I don't think I'll stop either. It's just that sometimes I have zero ideas, but I can paint — I don't need to have a super insightful thought or brilliant idea, of how I'm feeling or how the world's going. I just paint, because that's the system of producing work in place. On the other hand, sometimes I want to respond to things, and I can do that too. Maybe it's self-delusion that I can do both. That might specifically have to do with how we're taught in art school. Art schools nowadays are very open to students deciding what kind of practice they want to have.

Art schools and art education do very much influence the way an entire generation approaches art. You yourself have taught art for a while now. How does that influence your art-making?

Before I started teaching, I didn't have this concept of figuring out systems. It's only through teaching, through wondering how to train kids to do a project from start to finish, that I realised it's the system and process that's in between.

Teaching has influenced my practice in that the process has become an integral part in what I do. Art would be too linear without the process.

Having a process, you can choose to make up your own rules and then twist them. The process is the most fun part of art-making. The beginning sucks — you have no idea what you're doing — and the end sucks — it's too boring. It is then the process that is the most intriguing. That is what you can continue to modify, to change, to improve. Once the kids figure out what process they need, they can apply it art and everything beyond.

Students also give me hope. They're so impressionable, and unrestricted. Adults are often limited by conventions and practicalities. But kids, they are not so. They are more “naked". They tend to have a more direct way of getting from A to B, which is nice in some ways. A lot of times, as we get older, we stop doing things because we realise there are a lot of obstacles to getting there. Kids are less worried about these obstacles.