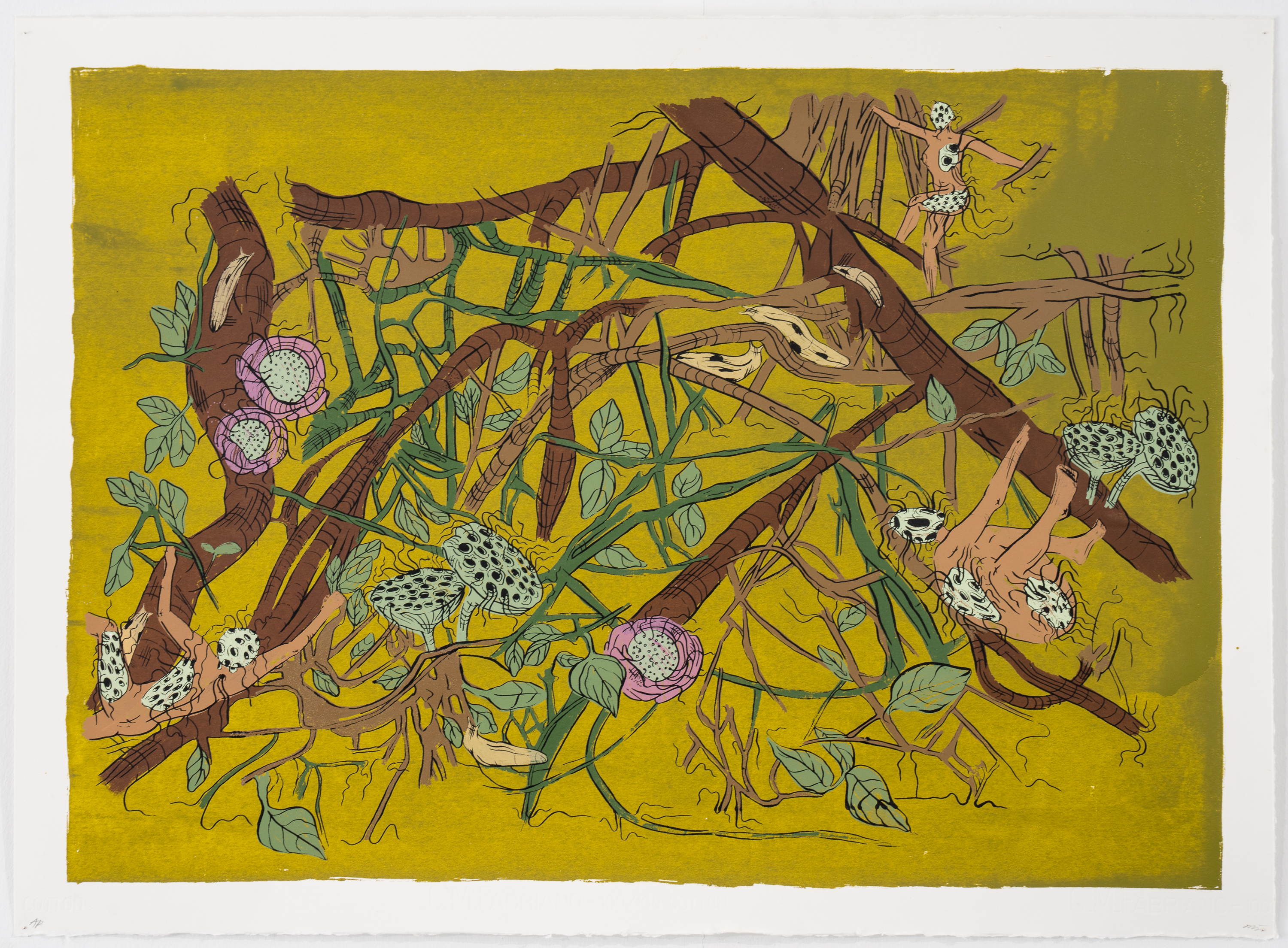

Mithra Jeevananthan (b. 1994) is a visual artist whose practice is strongly influenced by the amygdala. She creates fictional landscapes that are intimately bound up to represent the interior of her mind. These landscapes are imagined and non-binary. She uses the fluidity of sexuality and emotions to construct these spaces. The spaces she creates are innate as she projects her emotions in a narrative sense through various symbols. Within her prints, she creates landscapes that houses her Lotus Chimera. The Lotus Chimera is birthed from the writings of Donna Haraway and the “ero guro nansensu” art style. This chimeric entity lies somewhere in between one and two, incomplete and exists as a fabricated hybrid. Having graduated from Lasalle College of the Arts with a Bachelor of Arts (First Class Honours), she has exhibited in various projects and group exhibitions.

We first came by Mithra’s mind bending collages last year through her participation in the exhibition, Head Spinning, Loop Creating. Her works have a way of unsettling audiences, and that almost seems to be the point. Ever since the artist graduated from school last year, she’s been experimenting with more digital modes of illustrating and print-making. We talked about some of the works that have inspired her over the years, and her sustained interest in printing with silkscreen.

We first came by Mithra’s mind bending collages last year through her participation in the exhibition, Head Spinning, Loop Creating. Her works have a way of unsettling audiences, and that almost seems to be the point. Ever since the artist graduated from school last year, she’s been experimenting with more digital modes of illustrating and print-making. We talked about some of the works that have inspired her over the years, and her sustained interest in printing with silkscreen.

1998 – 1999

Let’s kick things off with your choice of Tokyo Police Gore and Junji Ito’s Uzumaki. The aesthetic of Japanese manga, in terms of its imaginative landscapes and depictions of social anxieties, shares clear affinities with your own artistic style. Why do you find yourself drawn to such a visual language?

Everything I do stems from the fact that I’m a printmaker, and the main medium I work with is silkscreen. When I work with silkscreen, I see flat colours. Even though I’m not Japanese myself or a manga artist per se, mangas were my first point of artistic reference. The concept of working with flat colours and simple, generic shapes came from my encounters with manga. Over time, I began to notice how fluid the lines were with manga as well.

When I first started making art, I was interested in the idea of the monstrous feminine. This meant that I was interested in figures such as the Pontianak. It was through Junji Ito’s works, funnily enough, that I learnt about The Monstrous Feminine. In Ito’s works, he has characters such as Dissection Girl or Slug Girl that are, for lack of a better word, weird. I suppose the chimera I work with draws heavily from Ito’s works as well. The chimera is a composite figure, with different parts joined together in a vulgar, strong and monstrous way.

I watched Tokyo Police Gore much later. Again, you have similarly-named characters such as Dog Girl and Snail Girl. In the movie, these female characters killed men. I think that’s where everything started for me, and how my idea of feminism changed.

Would it be accurate to say that what started out as an admiration for the techniques used in Japanese manga later morphed towards shaping you ideologically as well?

When you consider the works I’ve done — be it silkscreen, digital or murals — everything begins with layers of flat colours.

It’s almost like working with an artwork in Photoshop. Everything is in stacks. That’s just how I approach creating my works.

Let’s talk about the medium of printmaking for a bit. As you mentioned earlier, you work primarily with silkscreen. In recent months, we’ve seen you branch out into different types of printmaking. Your work at Fantasy Island, for example, was made with risograph. Having worked with a couple of different printmaking methods before, what did you find unexpected or interesting about risograph printing and its processes?

With risograph printing, everything is done digitally so it stood at odds with everything I had known. When I worked on the print with Knuckles & Notch, it almost seemed like everything I learnt about printmaking was thrown out of the window, which was so interesting.

Did your approach for conceptualising these works differ as a result of how digital and silkscreen printing methods diverge?

It was a lot easier, surprisingly. It was so easy working with the people at Knuckles & Notch. They gave me instructions for every step of the way, and I just had to follow them. In comparison, working on a silkscreen print can be quite a long and drawn out process. I’d have to drawn the image out, split them up into layers, and then apply colours to these layers. Even after doing all of that, things will fail a couple of times before they work out. As an artist, there’s always this room for trial and error.

Printing digitally is really about keying everything in correctly. The work was printed out so smoothly. I mean, this could also be because I wasn’t the one printing it. Another thing about printing digitally is how easy registration is. When I’m doing registration for my own prints, I’m standing there to align everything myself and it’s a very tedious process. It’s a small but important process, and printing digitally makes it a lot easier.

³ Passionfruit, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

⁴ Jelly Tiddy, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

2018

⁴ Jelly Tiddy, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

Let’s talk a little about your primary medium: silkscreen printing. Why do you enjoy working with a printing method that’s more physical in nature?

This is going to sound very cheesy, but I think there’s more heart to it when you’re working on something slowly, layer by layer. It takes a lot of time to mix the colours, and to prepare them at the start of a work day. You don’t know if the day is going to be good, or if all the prints you make are going to turn out horribly. There are a lot of things that can turn up unexpected when you work with a medium such as silkscreen. When you print in silkscreen, it can often take up to a week to finish just one print. It costs a lot more money, but there’s always that rush of adrenaline that comes from getting something right.

With a digital print, on the other hand, you can always just go back and erase something you don’t like. I know when audiences see the final print exhibited in a space, they aren’t thinking of the sort of processes that have gone into making the work. But I do enjoy it a lot more.

⁵ Reformatted “Paradise", Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

2018

You’ve touched on the lotus chimera a few times now, and it is an image that emerges quite often across your work. Could you tell us more about how you started working with the lotus chimera?

I thought the chimera, and the act of combining symbols together, would be the best way for me to talk about the female body without actually depicting the female body. When I was still a student, I thought that I would create work based around Indian skin, pores, hairiness or ashy-toned skin. The lotus pores came to mind immediately because there is this common analogy that links the female body to flowers. There are still people who refer to the vulva as a blooming flower, and I don’t understand why. The woman is always demure, pure, pretty, and clean. It is almost as if she’s not allowed to be vulgar, strong, or bold.

The lotus chimera in my work is almost an alter ego. The lotus chimera is a lot less nervous than I am, and it a vehicle for me to address all of the things I just talked about.

You’ve worked with this alter ego for awhile now. How has your relationship to or understanding of the lotus chimera evolved since?

Over time, I’ve tried to be less serious about the lotus chimera. When I first started working with it, it was very intense. I would aggressively defend my usage of the lotus chimera in my works. When lecturers asked me about the character, I’d be very adamant about its importance to me. Things have changed since then. The lotus chimera is still something I’ll explore in my works, but I’m trying to do this in subtler ways. I don’t think the lotus chimera is as evident in my prints as it was before, and I know that some of my prints can make viewers very uncomfortable as well.

Your works do unsettle viewers quite a bit, particularly if they have trypophobia. Moving beyond that, your works have the ability to confront some of the deep-seated anxieties viewers might have as well. Despite that, you haven’t shied away from using these images or characters in large scale works as well. You worked on a mural for the Facebook office in Singapore as part of their Artist in Residence programme. How was that experience like for you?

⁶ FB AIR Commission, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

2018

⁷ Garden, Marc Quinn

2000

That could also be reflective of the anxieties we were talking about earlier. Viewers often want to know exactly what a landscape or artwork depicts. Your works operate outside of conventional norms, and employ shapes and styles that are completely alien. How do you approximate something that sits outside the framework of binaristic human perception?

This all stems from my interest in the amygdala. I wanted to create a mental landscape, and I was inspired by Marc Quinn’s Garden as well. In Garden, the flowers are kept within a refrigerated containment. Although the flowers in the artwork look as if they are in full bloom, they aren’t alive anymore. Despite this, they live forever as dead flowers. I was interested in this manipulation of nature.

The landscapes I want to build are closely related to these ideas. These phantasmagorical landscapes don’t technically exist in real life, but they exist in my mind. If someone else comes along to view these works, they might have their own perception of what these landscapes are or mean. If someone looks at the lotus pores in the print and is completely disgusted with it, that’s fine. If someone sexualises the lotus chimera in these prints, that’s also fine.

These landscapes are chimeric. They are meant to be ambiguous and weird. They also aren’t supposed to make sense.

Landscapes are blank canvases. They can function as backdrops, or serve as gathering spaces. How do you understand or approach the landscapes in your works, especially because they are as much about physicality as they are about evoking emotion?

As I said before, these landscapes are chimeric. On top of that, they are queer or non-binary spaces. Fluidity is very important to me. When I make these landscapes, I make sure to emphasise the fact that they are completely mutable, and that nothing within it is fixed.

The first print I made of the amygdala as a landscape was probably the closest to exploring this as a part of the body. I included depictions of neurons, and bedding that was meant to replicate the notion of skin. It portrayed the amygdala as a cocoon, and all of my later works have stemmed from that. I put whatever I’m feeling at a particular point in time into a print. As such, it’s often difficult for audiences to fully grasp something that’s so personal.

⁸ Various Works, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018-2019, Installation View at Head Spinning, Loop Creating

Photography: Ng Wugang

⁹ Floater, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

Photography: Ng Wugang

2018-2019, Installation View at Head Spinning, Loop Creating

Photography: Ng Wugang

⁹ Floater, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

Photography: Ng Wugang

You were involved in Head Spinning, Loop Creating, an exhibition that explored how anxieties could be manifest within the physical space of a gallery. The exhibition was held more than a year ago and since then, we’ve seen conversations surrounding mental wellbeing develop quite a bit. As an artist who explores these topics, have you seen your own relationship to mental landscapes evolve since then? If so, how have you seen this understanding seeping into some of your newer works?

Coming back to the question, I don’t think I’ve ever stopped creating work that touches on the mental landscape. The works that I did for Head Spinning, Loop Creating were actually made in response to the exhibition space. The exhibition was held in Gillman Barracks. Before the exhibition started, I did a quick site visit and took a couple of photographs of the vicinity. Whilst the works sat within the compound of Gillman Barracks, I wanted the print to reflect the environment of the exhibition space as well. As such, I don’t think I’ll ever look towards bringing those prints back. I think they belong in that space. They were made for that space. This carries forward to the works that I’m making today, and the works that I’ll be making. They will all be made with a particular space in mind.

This creates a completely new definition of what it means to create site-specific works. Would you consider your process as one that is spatially sensitive?

I’m very attached to this particular space in the printing studios at Lasalle. I decided to bring that concept to Head Spinning, Loop Creating because my works have always been about landscapes — both mental and physical. Now, I do a lot more digital works. If I’m drawing in my room, I tend to include symbols such as my dog, furniture, or my friends. If I were to ever move to a different country, my works would probably draw upon the things that I see around me at that point in time as well.

¹⁰ Cereal Bowl, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

Photography: Ng Wugang

¹¹ Sea Forest, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

Photography: Ng Wugang

2018

Photography: Ng Wugang

¹¹ Sea Forest, Mithra Jeevananthan

2018

Photography: Ng Wugang

¹² Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway

1993–2009

When you describe your work, words like “part” or “hybridised” emerge frequently. This can give the impression that the focus is on the components that comprise the whole. On the other hand two of the works you’ve picked out, The Pandrogeny Project and Cyborg Manifesto, rethink how gender and its boundaries can be pushed towards a sort of oneness — either a fission between humans, or between organic and inorganic matter. You talked a bit about how important fluidity and the exploration of fluidity is to your work, but what does it mean to you?

When I think of the hybrid being, it stems from my reading of the book, Cyborg Manifesto. I took the word “chimera” from it, and everything has grown from that single word. Whilst preparing for this interview, I reread my dissertation. I wrote about the chimera extensively, and I split the thesis up into different headings such as “The Sexual Chimera” and “The Porno Chimera”. When I saw The Pandrogeny Project, I just saw two people becoming one. It was so wholesome, and that was it. I also liked how they coined their own term, and I wanted to coin my own term for the lotus chimera. For example, Takashi Murakami has a very distinct artistic style and identity. Audiences are familiar with and would recognise his Superflat works.

Coming to the concept of gender identity and feminism, at times it does feel like these concepts have been overdone. I wanted to create works that referenced the female body, but I also wanted to stray away from feminism. Feminism can be very tiring sometimes. It is often brought up in sessions such as artist talks. Although artist talks are important spaces to dive into the process of creating particular artworks, the artworks should speak for themselves as well. I shouldn’t have to go on about feminism because the work should already encapsulate that clearly.