Nandita Mukand is a Singapore-based artist whose practice encompasses sculpture, installation and painting. Nandita’s work was included in the OpenART Biennale (2017, Sweden) and Imaginarium: To the Ends of the Earth (2017, Singapore). Other notable exhibitions include solo shows such as Mind(less) Wilderness (2019, Singapore), Forest Weft, City Warp (2017-2018, Singapore), The Materiality of Time (2015, Singapore); and group shows such as From Lost Roots to Urban Meadows (2019, Singapore), Exploring the BigCi (2015, Australia), Untapped (2016, Singapore) and Fundacio L'Olivar (2016, Spain).

Inspired by seeds and flowers, Nandita’s practice takes reference from the natural world. Dried plants, pods and sinuous webs are commonplace in her artworks. We met with the artist in her studio, and talked to her over hot tea and snacks. The artist has a brightly lit and airy studio space at home, and we sat surrounded by works of hers — both hung and framed, or mid-process.

Inspired by seeds and flowers, Nandita’s practice takes reference from the natural world. Dried plants, pods and sinuous webs are commonplace in her artworks. We met with the artist in her studio, and talked to her over hot tea and snacks. The artist has a brightly lit and airy studio space at home, and we sat surrounded by works of hers — both hung and framed, or mid-process.

¹ Exposing the Foundation of the Museum, Chris Burden

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1986

You’ve always been intrigued by time aspects of growth and decay, and we see this in many of your works. The notion of time passing is a process, and it is often difficult to distill into a single portrayal or depiction. Artists, such as Chris Burden, have done so through immediate and marked interjections into physical landscapes. Personally, how have you grappled with this conceptual difficulty within your practice?

I’ve used many different strategies to do so, but I think many of us find it difficult to grasp or think about this passage of time because we live in the city. If you look at the city around us, particularly when you observe older architecture, you can clearly see that these buildings were of a different time. They have their own forms, and use different materials. Now, in comparison, we have architecture that looks very clean and almost block-like. Everything is very sleek, and even the interiors are incredibly polished. We see materials such as chrome or glass being used, and these are very modern materials, but they do not show the passing of time. Thinking about it on a more personal level, many of us live in high-rise apartments that are air-conditioned and have electric lighting. We don’t think much about how time passes at all. On the other hand, when I’m in the midst of nature, I feel as if everything points towards this passing of time. I pick up these clues, and incorporate them into my artworks. Let’s take the bark of a tree as an example. Tree barks tend to have fungi or moss growing on them, and they’re often a roadmap of the tree’s lifespan. There are all these layers built up, and this is what interests me. I bring these markers of time passing into my work.Another thing about living in the city is that we get so used to seeing these straight lines and edges around us. When you look at things in nature, things tend to form in a very organic manner. For me, this tends to point towards the idea of growth. That, again, comes back to the passing of time. Referencing these forms help me to explore the passing of time within my works.

Materials are also incredibly important to me. Often, I like working with dead plants or organic materials. These materials are ephemeral, and directly evoke the passage of time. These are just some of the strategies that have helped me throughout my practice, and all these strategies work differently.

A couple of years back, I worked with the OpenART Biennale in Sweden to create an artwork out of dried flowers. These dried flowers came from bouquets that members of the general public contributed. These bouquets were markers of important experiences, such as wedding bouquets. It was a very fragile installation, and I wanted to create a piece that commented on the fragility of life and how everything is fleeting.

Even if the material itself does not evoke the passing of time, sometimes the process of making a work does. I have this repetitive process of working on something continuously, and through that process again, time passes. It becomes almost a meditation on how we experience time in the city.

² Essere fiume (I), Giuseppe Penone

1981

It’s great that you touch on using materials such as plants or dried flowers. Your selection for this interview also comprises objects such as seeds and trees, and artworks such as Giuseppe Penone’s Essere fiume (I). Tell us about how your interest in nature began, and why it continues to fascinate you and invigorate your practice today.

I don't know exactly how it began, but I think it must have started back when I was very young, My family used to live down in the foothills of the Himalayas. Maybe it was then that I fell in love with the mountains. I love the mountains, I love the forests, and I love the trees. Now, for the most part, I live here in the city. But when I go back and I’m in the mountains again, I experience this deep sense of homecoming.

That’s what really intrigues me. I am, technically, still the same person. Yet why do these various environments draw out such different things within me? That’s what, I think, forms the very basis of my practice. I aspire to be the person that I am when I am within nature. Yet when I live in the city, I am unable to. I feel like all of us struggle with this. There are, of course, many different ways of accessing this sense of self. Some turn to meditation or prayer.

For me, surrounding myself with nature is how I get in touch with myself. It gives me a totally different perspective.

I’ve seen these beautiful trees in East Coast Park on my walks there, and I’m incredibly aware of the fact that they’ve been here for generations just listening to people. They’ve been here before I was born, and they’ll continue to be here after I pass on. They’ll still be listening to the conversations people have about their worries, their desires, and the ups and downs of life. It puts everything into perspective immediately. Time is expansive, and my life is but one small speck in that. These large trees come from tiny pods or seeds, and I find that amazing. Seeds are so small, but they contain so much life and potential within them.

I picked Giuseppe Penone’s work out for our conversation because I love his work. Penone was part of the Arte Povera movement, which resonates a lot with me. Penone’s work speaks of being physically in touch with nature, touching nature and molding things in the likeness of nature. The work Essere fiume (I) essentially comprises two stones. Penone collected the first stone from the river. He then went to the source of the river, extracted the type of stone there, and began carving out a stone that looks identical to the one he collected. Essentially, he became the river. I thought that was beautiful.

It is an incredibly poetic work and gesture, and ties in really nicely to the trees you spoke about. It brings to mind some of the larger or older trees that have been felled recently in order to make way for more construction or development.

Definitely. I think it raises questions as to the psyche behind all of this.

What makes us want to cut these trees down? What are we trying to create by getting rid of this? What sort of ambition or desire that compels us to do this?

³ Urban Veil 1, Nandita Mukand

2019, Installation View at The Private Museum

Credit: The Private Museum

2019, Installation View at The Private Museum

Credit: The Private Museum

When we met for coffee prior to this interview, you said that you primarily work across three mediums — painting, installation and sculpture. Having said that, one might not see such a clear material distinction when encountering your work: a painterly sentiment can be seen within your sculptural works, and some of your paintings can be described as sculptural as well. As someone who works closely with a variety of different mediums, how do you think this intimate understanding of working across various techniques and materials has shaped your perspective?

Recently, I’ve been working with cloth quite a bit. When I work with cloth, I try to emphasise how the cloth has been weaved together and its weft and warp. I want that to be very clear and visible within the artwork. That represents, for me, the connections between the city and the natural.

Everything is connected. If you pull on one thread within the fabric, everything else unravels very quickly.

I think working with these various materials allow me to touch on all of these different aspects of life in a very visceral and immediate way. Sometimes, I even coat my work with a very thin layer of plastic. Plastic can be read as being symbolic of or a contemporary of our current material culture. They do flow into one another.

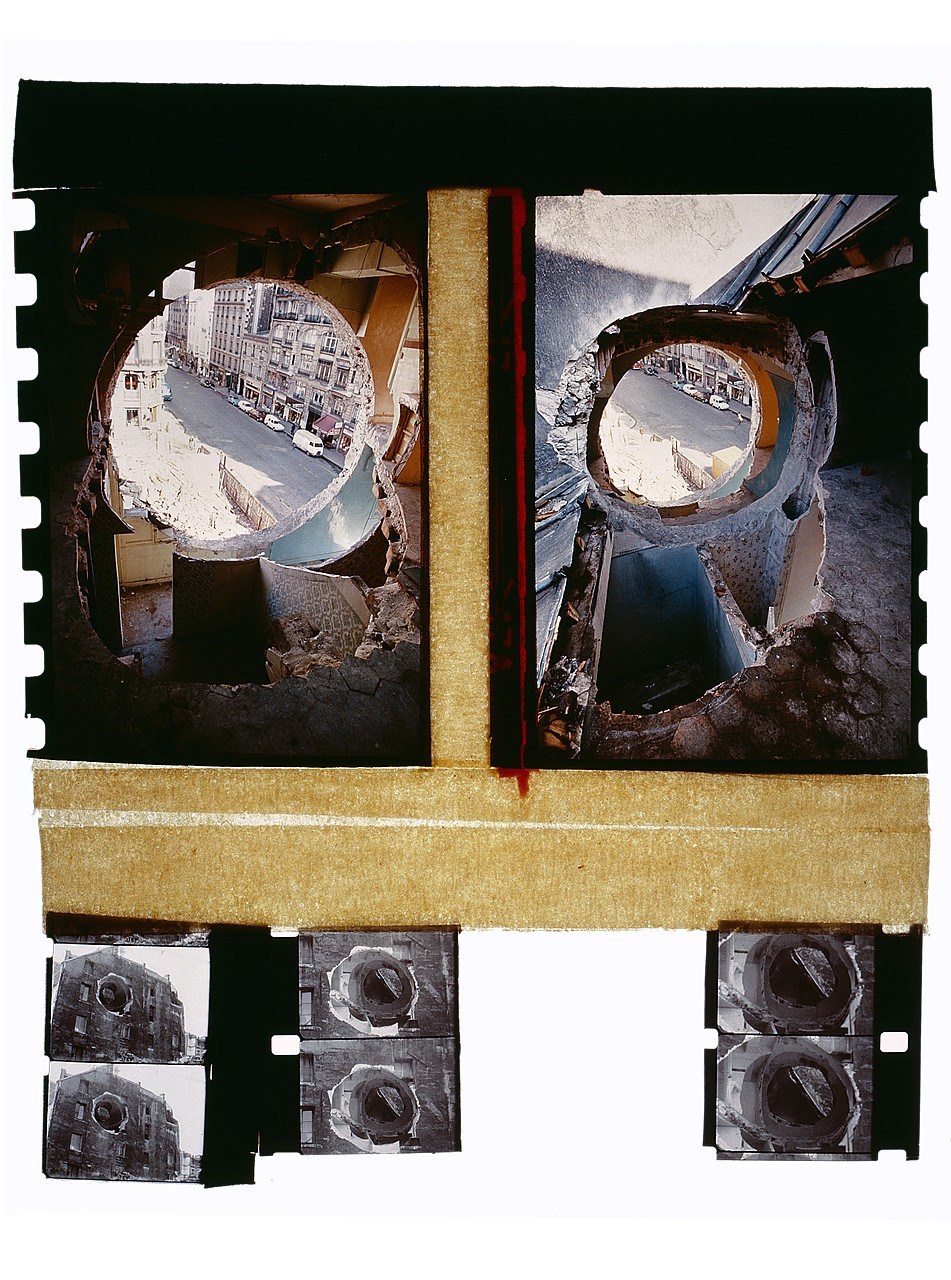

⁴ Conical Intersect, Gordon Matta-Clark

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1975

The form of your sculptural works can be described as organic and sinuous, yet they are keenly aware of the immediate cityscape that surrounds us — and often, reimagine how we can navigate or experience the urban. In that sense, it shares similar ambitions to what Matta-Clark sought to do with Conical Intersect. Could tell us about what it is you enjoy about this particular work, and how you first encountered it?

I read a lot of Robert Smithson’s writings, and he always talks about entropy and how that is always constant. I find entropy, as a concept, really interesting. It is a scientific term and comes out of a Western tradition, but I find in it a lot of parallels to Eastern concepts of embracing temporality. Everything is constantly changing, and I enjoy seeing Eastern and Western worlds coming together in this one concept. Gordon Matta-Clark was similarly inspired by the writings of Robert Smithson. Smithson was once quoted as saying: “The city gives the illusion that earth does not exist.” That really resonated with me. It is such a simple statement, but so incredibly profound as well.

Matta-Clark does these excavations into architectural buildings in order to study their forms. He was critiquing the ambition of these architects, particularly those who wanted to create buildings for all posterity. For Matta-Clark, the ultimate destiny of architecture is to go down the chute. In a way, these works are his take on ephemerality. Nothing lasts forever, and this is something that we think about a lot within Eastern traditions and philosophies. I find it so intriguing that artists in the West were thinking about these ideas as well.

Speaking of ephemerality, tell us about how you approach the process of creating your own works. Although they touch on similar ideas to Matta-Clark’s Conical Intersect, they are contemplative and striking in very different ways. In particular, I have in mind Urban Veil, a work comprising fifteen of these webbed, expansive structures.

I started the process of thinking about Urban Veil about five years ago. I was doing an artist residency in Australia then. The compound was surrounded by nature, and I was able to stay in the forest for the entire day. It suddenly dawned on me that we rarely have a chance to be surrounded by nature. When we do look at nature, we are often looking at it through a window — be it a car window, or through our digital screens. There’s always something that comes in between that experience with nature, we’re never alone in that. I began to realise that there is this veil that exists, and that comes in between us and our ability to experience nature. I began exploring this idea through dead plants, for example, and this has since been manifested in various works of mine. I'm also thinking about how the veil is constantly thickening.

When I made Urban Veil, I don’t think the fifteen structures have to be fifteen as such. Those forms were inspired by plants growing and decaying, so they were meant to be symbolic of the nature and its ephemerality. By putting them together and repeating these forms again and again, I think it emphasises that exact quality.

That leads very nicely into my next question. In a recent show at The Private Museum, you displayed works alongside ceramic artist Madhvi Subrahmanian. As artists you both share similar trajectories and interests, but approach these ideas from different perspectives. What did you glean from this experience of having your works placed alongside the works of another artist, particularly someone who works in a different medium?

It was a very interesting experience. It was not just about putting up the works within the space of a gallery. We spent a lot of time thinking about how we could curate it. We had extensive discussions around our two philosophies. Even though we're investigating similar ideas, it was very clear that we were doing so in totally different ways. Madhvi works primarily in ceramics, but I enjoy working in different media. I had a work in the show that was an installation made out of seeds. Another work was made out of paper. I also showed a series of photographic prints for this exhibition.

It’s difficult to pinpoint, but it was interesting to see how we managed to explore similar themes in such different ways. We each had our own style. I think it helped me to grow in terms of an understanding of myself — both as a person and as an artist. It helped me to consolidate my thinking a little bit better.

⁵ From Lost Woods to Urban Meadows

Installation View at The Private Museum

Credit: The Private Museum

Installation View at The Private Museum

Credit: The Private Museum

As a result of how intricate your sculptures and installations are, they often cast interesting shadows when lit from various angles. In a sense, the shadows created become an extension of the work itself. Given that your works possess this quality, do you have particular ideas around how you’d like your works to be displayed or lit when working with private galleries or art institutions?

The shadows are really important to me, and I love the shadows. Whenever I work, I usually give the installers a lot of grief. We could be trying for hours in order to get the right shadows. It’s a lot of trial and error. There are certain spaces and certain lighting conditions that allow my works to cast better shadows than others.

One work could also look very different from one gallery space to the next, so it's a lot of trial and error.

It is something that I can't plan for. It's usually totally out of my control. Sometimes, it also happens very spontaneously. There have been times where I’ve put a work up, and the light hits the work in such way that the shadows cast are fantastic. I couldn’t have planned for it, and I see it as a gift. It just happens.

I haven’t been able to pin down how exactly I approach this aspect of the work. In order for it to work, obviously you need good overhead light and to maintain a certain distance from the work. Ideally, I would like to have a lot of lights available so that I could play with different options. There are some venues that have track lights, and I often use those to adjust the different angles and distances from which light is cast onto the work. It also depends on whether I have the time to spend on installing the work this way. Often we’re rushing for time when we’re putting on a show, and I don’t have a day or two to spare on experimenting with lighting conditions. As an artist, sometimes it’s about letting go a little bit.

In paintings such as those in the Burn Your Old Stories to the Ground series, you incorporate sand onto the canvas. This, in turn, creates thickness and texture. Tell us about how you incorporate other materials into your painting, and why you’ve incorporated sand into quite a few of your paintings.

To begin with, I'm not a purist. I work with different materials. It doesn't bother me in that way. In fact, materials are very interesting to me. I’m interested in the connotations that they have embedded within them. Sand, for example, is a natural material. Working with sand was therefore a very natural process. It’s more about the layering, and particularly in a manner that reminds me of the passage of time. I’ve played around with sand quite a little, and it was a very spontaneous process.

⁶ Burn Your Old Stories to the Ground 1, Nandita Mukand

2016

⁷ Burn Your Old Stories to the Ground 3, Nandita Mukand

2017

2016

⁷ Burn Your Old Stories to the Ground 3, Nandita Mukand

2017

Your works do not shy away from the use of colours, textures and organic material. Tell us about why you’ve been drawn towards these visual and physical landscapes or lush abundance, and how you understand your role in creating them. Would you describe yourself as a collector, a collage-maker, or something else entirely?

I always start with the experience and thinking about and how I can bring that experience back into the studio. It’s about translating that into an object that will, in turn, facilitate that experience for the viewer. That is the process. The materials and colours I use are just tools, and they can all be adjusted in order to create that experience. I’m interested in creating a very visceral experience, particularly something that is sensuous and tactile. It draws the viewer in. We can talk about what I mean by using certain materials and colours in my work. However, I’m interested in what goes beyond the work. What can someone experience by looking at these things? Sometimes I am a collector of things, and other times I use collage as a technique.

Everything is rather flexible, and it always begins with exploration. As an artist, I’m constantly evolving. I’m always trying to find better ways of reaching within and expressing these ideas.