With the constantly evolving arts and cultural scene in Singapore, exhibitions come and exhibitions go. Yet rarely has an exhibition garnered as much critical engagement or as many think pieces as the recent Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman exhibition at the Asian Civilisations Museum. For many viewers, the irony of holding a well-polished exhibition about an exploitative East India Company official in a colonial building was not lost on them. How do we engage in civil conversation about a past fraught with injustices, particularly injustices that we still see traces of today? In this conversation, we speak to one of the exhibition’s curators about a batik textile featured in the show and the ways in which the curators have attempted to read these objects as historical documents.

Naomi Wang is an Assistant Curator for Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. She holds a BA in Art History from the University of Toronto. She joined the Singapore Art Museum in 2012, with a focus on mainland Southeast Asia. At the Asian Civilisations Museum, she specialises in Southeast Asia, with particular interest in the formation of Malay sultanates and metalwork tradition from the early modern period. She recently co-curated the special exhibition Port Cities: Multicultural Emporiums of Asia, 1500–1900.

Naomi Wang is an Assistant Curator for Southeast Asia at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. She holds a BA in Art History from the University of Toronto. She joined the Singapore Art Museum in 2012, with a focus on mainland Southeast Asia. At the Asian Civilisations Museum, she specialises in Southeast Asia, with particular interest in the formation of Malay sultanates and metalwork tradition from the early modern period. She recently co-curated the special exhibition Port Cities: Multicultural Emporiums of Asia, 1500–1900.

¹ Ciptoning

Yogyakarta, late 19th to mid-20th century

Credit: Museum Batik Danar Hadi

Yogyakarta, late 19th to mid-20th century

Credit: Museum Batik Danar Hadi

READING TEXTILES AS HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS

Naomi Wang (NW): This batik textile is one of four on display in the exhibition, and they are called batik kraton — batik made in the royal palaces of Central Java. The four textiles were produced by four different courts, all very intimately linked with one another.

All of these courts originated from the Mataram Sultanate, which flourished around the 17th century. In 1755, the Mataram Sultanate split into the Yogyakarta kraton and the Surakarta kraton. In 1757, the Mangkunegaran Princedom split from the Surakarta court. These three courts would have existed when Raffles arrived in Java in 1811, and the final batik on display is from the Pakualaman court. In 1812, Raffles attacked and sacked the Yogyakarta kraton. At the same time, he set up the princely Pakualaman court.

This particular batik textile I’ve chosen to focus on is from the Yogyakarta kraton, and what you see depicted on it are characters from the ancient Hindu epic, the Mahābhārata. Essentially, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyana are the oldest Sanskrit Hindu epics to come out of India. They were very well known and spread throughout the region via maritime trade routes. Characters from the Mahābhārata such as the prince, Arjuna; the spiritual teacher and author, Abiyasa (Vyasa); and Lord Krishna are depicted on this textile. The characters here are depicted in a visual language that recalls puppet figures used in wayang kulit. When you look at the sort of stories that are enacted in wayang, the Mahābhārata ranks amongst the most popular. So it is interesting that the medium of storytelling, wayang, is depicted on the batik textile itself as well.

Batik making, like the tradition of producing manuscripts, remains one of the highest forms of art within courtly society. A court’s ability to commission and patronise art is an important marker of its prestige and status. The more prolific the production of batik, the more projected a court’s sense of power is. Most of the major courts that still exist in Java today have their own batik making facilities and their own abdi dalem.

Central Java presents to us an interesting case study in that their school is Islam is a rather syncretic one. We see this through the manifestation of art from this region, and how Hindu-Buddhist iconographies and motifs have been incorporated alongside Islamic belief systems. We see that the commonly held notion of prohibition against figurative depiction did not really hold in the Central Javanese courts.

² Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman

Installation View at the Asian Civilisations Museum

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

Installation View at the Asian Civilisations Museum

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

³ Parang Barong Seling Naga

Surakarta, c. late 19th century or early 20th century

Credit: Museum Batik Danar Hadi

Surakarta, c. late 19th century or early 20th century

Credit: Museum Batik Danar Hadi

IDENTITY MAKING AND SELF FASHIONING THROUGH BATIK

NW: Batik are public forms of dress, so they shouldn’t just be seen quite simplistically as fashion or design. These batik cloths were made to be worn by members of the royal family and hold very deep cosmological, philosophical and political meanings. In batik making, the sort of motifs and colours incorporated actually reflect political upheavals or occurrences during the time. Batiks could also be used to proclaim allegiance, or declare independence and sovereignty.

In the context of the Yogyakarta kraton, this textile we have on display would have been characteristic of the sort of batik the court produced. A milk chocolate colour is applied on an undyed off-white base, and this sort of colour palette would have been synonymous with the Yogyakarta court. In comparison, the colour palette associated with the Surakarta court is quite different. Batik textiles from the Surakarta courts are distinguished by their use of deep reddish-brown hues on a dark indigo base.

Furthermore, certain motifs were associated closely to kingship and reserved for royal use only. This becomes an interesting marker of the sort of value systems that were held then. On the Yogyakarta Ciptoning, we see the motif of a garuda’s tail. The garuda is closely linked to notions of kingship in Java, and finds roots in Hindu notions of nobility and royalty. On the Parang Barong Seling Naga, we see a crowned Naga. Nagas are seen as spiritual figures and protectors.

Another important motif is the wave-like pattern known as the parang. If I were to directly translate parang into English from Javanese, it would mean “cliff”. This conjures up images of waves crashing upon the cliff, and the motif has become directly related to ideas of kingship. In the textiles we’ve displayed here, it’s quite literal — the size of the parang motif matters. We refer to the parang motif on the Parang Barong Seling Naga as parang rusak barong. Only a king would have been worthy of a textile with such a large parang pattern on it. If one wasn’t kingly enough, the spiritual and cosmological energy of such a large parang would overwhelm the wearer immediately.

In the Surakarta court, these textiles would be worn from the right to left, whilst in the Yogyakarta court, these textiles would be worn from left to right. You see that even the orientation of the motifs are used to further differentiate one court from another. These motifs are so codified and regulated, and these traditions have continued up until today. Yet because these motifs are so codified, it would seem like a whole new language to someone who wasn’t Javanese. There isn’t a manual that helps one decode these meanings. Today, anyone would be able to adorn batik textiles with such motifs. But in those days, these textiles would have most definitely been made for someone of royal status.

It can be argued that mediums such as batiks can also be used to communicate messages or convey stories. The Mahābhārata story depicted on the batik from the Yogyakarta kraton is, in and of itself, a travelling text. Through modes of migration and retellings, characters within this epic take on different forms in different places and mediums. These stories are told through wayang, traditional dance and can even be found on architectural stone reliefs. For example, some of the stone reliefs at the 9th-century Prambanan temple complex feature allegorical scenes from the Rāmāyana. Based on this, we know for a fact that the Javanese people would have known of these stories as early as the 9th century. When batiks such as this depict allegorical scenes, it can be said that they are part of the continued proliferation of these stories.

When we read Raffles’ accounts of the Javanese courts, it becomes clear that he saw them in a very monolithic manner. He summarised the Javanese people in a very taxonomical manner — the Javanese consumed this, or the Javanese produced that. Just by including this small display of textiles from four different Central Javanese courts, it becomes clear that the way in which Raffles wrote about the Javanese people was both incorrect and inaccurate.

⁴ Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman

Installation View at the Asian Civilisations Museum

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

Installation View at the Asian Civilisations Museum

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

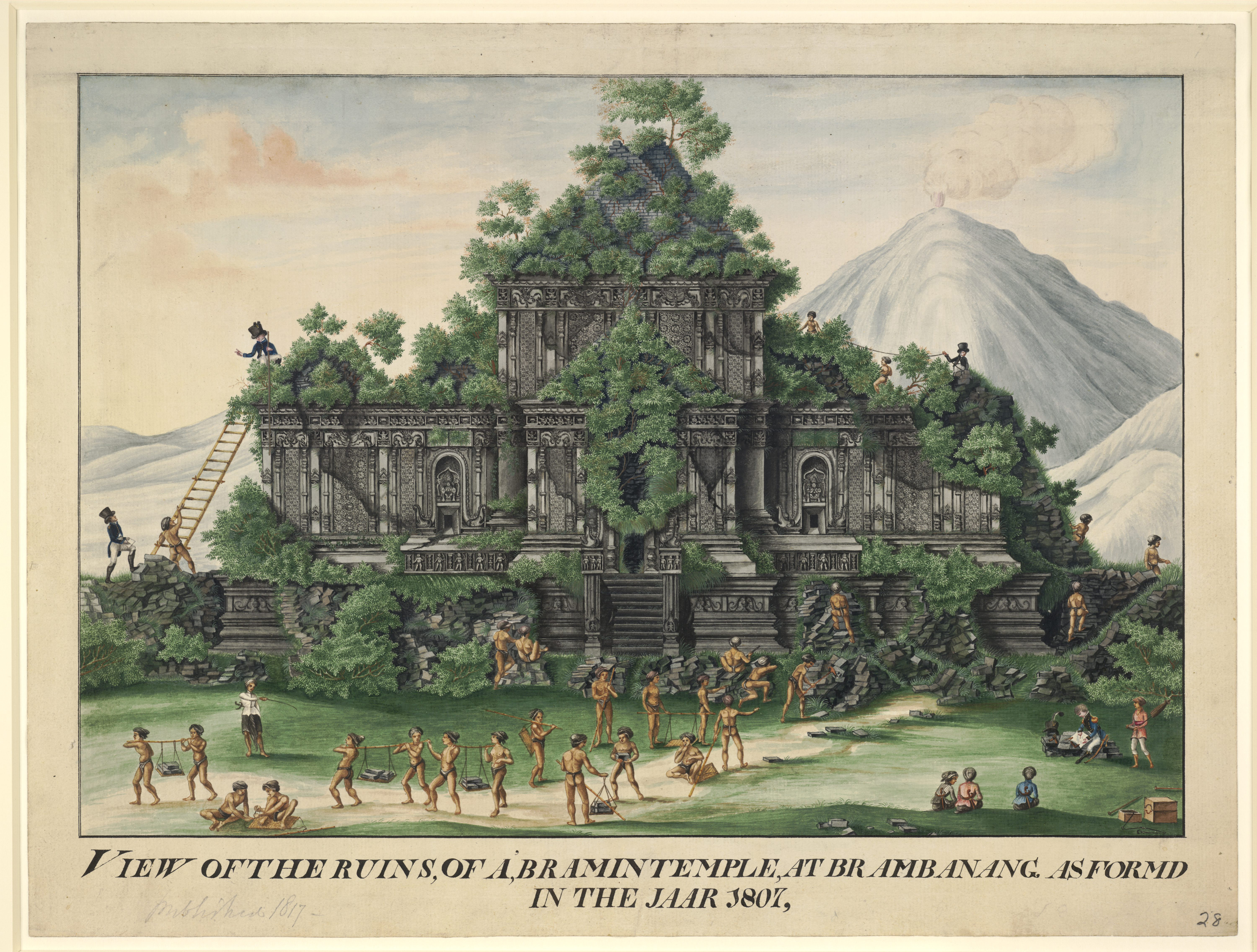

⁵ Fanciful view of Candi Sewu being cleared by Javans under direction from Europeans

Java, 1807

Credit: British Museum

⁶ Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman

Installation View at the Asian Civilisations Museum

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

EXHIBITING A TRAIL OF EVIDENCE

NW: The first part of this exhibition looked at Raffles’ own collection — that is, the very collection he put together whilst he was in Southeast Asia. For us, it was important to showcase this colonial gaze in order to interrogate and expose it. Throughout the first section, we see these objects collected in sets and groups. This was a very colonial method of collecting, where one would do a survey of a society and its people without much depth. We tried to address this through the object labels. For example, the two batik cloths Raffles collected were meant as samples for manufacturing purposes. They weren’t collected to represent the fine arts of Java. In fact, the two batiks he collected were rather poor in quality and design, and were clearly not of palace manufacture. It was clear that the cut of the cloth mattered more to the European gaze, and that’s why you see that some of Raffles’ batiks have been altered into dress or skirt patterns.

The second section of the show is us trying to address or respond to Raffles’ collection. If the first section of the show was about what Raffles collected and why he collected those objects, this section answers the question of how he collected. He certainly would not have been able to collect the things he did, publish the books he did, get knighted or become a celebrity if not for the major upheavals he wreaked in the political systems of Java and the larger Malay world. We wanted to look at the wars he waged in Java, and the sort of war booty and plunder he took.

This display of batiks towards the end of the exhibition represent the voices on the ground. These are the courts that Raffles dealt with. When we read European narratives of this time and place, we get a very one-dimensional perspective of the Javanese people. For a long time, these narratives were privileged and held as the de facto authority on these cultures. By including these textiles in the exhibition, I wanted to point audiences towards the deeply complex reality of the Central Javanese political and social landscapes. Essentially, these are visual representations of how the Central Javanese courts saw themselves and each other, and even touches on ideas of political rivalry.

There have been several exhibitions that have been done around the figure of Raffles, but none have looked critically into his collection. Alexandra Green, the curator for Southeast Asia at the British Museum, has published extensively on the shape of Raffles’ collection. This includes hard qualitative data on his collection. Out of his collection of more than 2000 objects, over 650 were wayang puppets, and more than 100 were bronze sculptures. There was a clear bias against Islamic material as well, as Raffles only had two artefacts that related to Islamic material in his collection of more than 2,000 objects. This has been a point of great puzzlement for scholars because by the time Raffles arrived in Java, a vast majority of the population would have been Muslim.

FROM EVIDENCE TO INTERROGATION

NW: Raffles is a very polarising figure. We have monuments erected in his name, we have the best schools and institutions in Singapore named after him, and the museum itself is located on Raffles Place. So much of Raffles, in terms of who he was, has been mythologised. When dealing with such a polarising figure in popular history, it becomes all the more important to look at facts, evidence and data. The best way we thought we could do that was to look at his very own collection, and to look at the sort of scholarship he produced.

By interrogating the shape of his collection, we were able to question why he collected some things over others. This became the hard data that evidenced the fact that Raffles had many misconceptions about Java. We wanted to lay out the evidence of Raffles’ less than noble intentions in collecting Javanese antiquities, and the sinister economical motivations involved as well. The objects on display here were plundered from the kraton itself. This is not often addressed when we look at Raffles, so this last section of the exhibition really looks at things that are rather visceral.

We wanted to lay all of this out in an evidence-based manner in order to question how one goes about collecting knowledge. Once this knowledge is collected, how then does one repackage this information, and to whom is this information presented to? Through his collection, it becomes very clear that Raffles’ view of the Javanese peoples was racist. They, like their economic produce and goods, were things to be subjugated. I hope audiences come away from this exhibition realising that any opinion on the matter has to be formed based on the facts. It isn’t good enough to say that colonialism is bad. We have to know how it was bad — the wide-ranging and sinister ways in which it was bad.

When we read Southeast Asian history, it is important to question who the gatekeepers of knowledge were. Particularly with this colonial period, many of the European sources on this region are written in English. We also need to consider what sort of books get published, what sort of materials are circulated and how much these books cost. This last section of the exhibition tries to go against the grain of the European narrative about Java. Raffles’ assault on Java was brutal and violent, and it completely annihilated the Yogyakarta kraton. Yet, this isn’t common knowledge. We looked at a Javanese source that chronicles the fall of Yogyakarta and in a very small way, this helped me to see this period of British Occupation through a Javanese perspective. These material objects on display aren’t just beautiful objects. They are historical records and witnesses to that specific moment in time. Through objects, we try to point audiences towards looking at history from the right perspective — a perspective that is non-European, and that is of this part of the world.

Raffles in Southeast Asia: Revisiting the Scholar and Statesman is now open.

The exhibition will run at the Asian Civilisations Museum until 28 April 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

The exhibition will run at the Asian Civilisations Museum until 28 April 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.