Nature Shankar is a Singapore-based visual artist whose practice mainly revolves around textiles and the method of hand embroidery. Her work questions the dynamics of truth, healing, race, cultural heritage, roots of internalised biases, and existence. Nature was the recipient of the Woon Tai Jee Art Prize, completed her BA Honours at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, in partnership with Loughborough University. Her works have been exhibited at the ArtScience Museum (2015, Singapore), Ngee Ann Kongsi Galleries (2016, Singapore), Hive Gallery and Studios (2018, Los Angeles), and Gajah Gallery (2018, Yogyakarta).

Although textiles have been integral to the cultural makeup of various communities across time, they have been often associated with the notion of craft. In recent years, we’ve seen that perspective shifting with the rise of embroidery and textile artists, and the blockbuster fashion museum exhibition. We spoke to Nature about the works she draws inspiration from, her practice, and where she sees herself moving towards next. The artist picked out artworks by Ragnar Kjartansson and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and a film directed by the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer for our conversation.

Although textiles have been integral to the cultural makeup of various communities across time, they have been often associated with the notion of craft. In recent years, we’ve seen that perspective shifting with the rise of embroidery and textile artists, and the blockbuster fashion museum exhibition. We spoke to Nature about the works she draws inspiration from, her practice, and where she sees herself moving towards next. The artist picked out artworks by Ragnar Kjartansson and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and a film directed by the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer for our conversation.

¹ Cloud Atlas, directed by the Wachowskis and Tom Tykwer

Cloud Atlas, the movie you picked out for our chat, is a film adaptation of the novel of the same name. It encompasses the lives of several people across great expanses of time, and remarks on how the life of a single person can have reverberations far beyond one’s own time. Tell us about your own relationship to the film, and why you felt compelled to pick it out for this interview.

I first watched the movie in 2012, and have watched it countless times since. What drew me towards the film was its ability to capture time — not just our own time, but the times we pass through and a variety of lifetimes. Throughout the film, there is this sense of unity. It touches on the lives of these six people, all of whom have no knowledge of each other’s existence, and yet they somehow feel this connection to one another.

Within my own practice, I’ve always been very attracted to this unexplainable pull or attraction. I’m not able to explain it fully in words, but it was the entire experience of watching the film in conjunction with hearing the soundtrack. We’re all tied to one another.

I was also intrigued by the idea of the butterfly effect, particularly how a single human action can result in a series of resulting consequences that could have never been preempted or predicted. For example, we could release balloons into the air in the name of art. Yet, these balloons could trigger fires that cause significant, irreparable harm to the area and its landscape. The film touches on this weight of responsibility, and the gravity of how the consequences of just one action can be compounded through the ripple effect.

The film received backlash after reports of “yellowface” surfaced. I’m still struggling with that conflict of morality. It is a film, and it is a work of art. How, then, do I feel about them using yellow face? Was it necessary to the storyline? What started out as an interest in a science-fiction film soon evolved into a growing awareness of an artist’s role and responsibility. Every time I watched the film, I would unearth something new.

Have you read the book? How does the book compare to the film adaptation, and how have the two helped elucidate or solidify your connection to the story and its themes?

Coming across the book and picking it up was a coincidence as well. I was still a student at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) when I came across a second hand bookstore at Bras Basah Complex holding a massive sale of its books. I had just watched the movie either that week or the week before, and the novel was the first book I saw when I walked in.

Do you find that you’ve been able to visualise the scenes in the book better because you watched the film first, and if so, do you approach reading as a visual experience?

I would say that they have to go hand in hand. When I began reading the book, it took awhile for me to make the connection between what was happening in the book and what happened in the movie. I think of both the book and the movie as being visual mediums, although they are separate works. It’s important to figure out the differences between the two as well.

When the movie was first launched, everyone was telling me about how bad it was. That’s actually how I first heard about the movie.

We talked about how much you enjoy love stories, and Cloud Atlas speaks to emotional connectedness. On the other hand, the other works you’ve picked out touch on how people fall out of sync with each other. Before we dive into those two works, let’s talk about the underlying sense of time that runs across all three works. Despite their similarities, all these works explore the notion of time differently. Your work, 22 Years of Thickskin, references time in its title as well. Were you mulling over the concept of time and passing time when making this work?

This is the first time I’ve had to sit down and think about works that have inspired me, and these three works have always been on my list. I constantly remind myself of how important these works are to me, but I’ve never really put them down on paper before. When I sent these three works across to you, I started noticing their similarities. They all discuss desire and yearning, and that’s when I realised that I really am a sucker for such works.

When I talk about love stories, I’m not referring to works by authors such as Nicholas Sparks. Sparks himself has been the centre of controversy lately for his rather racist and homophobic views. If you give me Romeo and Juliet, I’d probably pass on it. I find the actual love story secondary to the overarching ideas of connection and unity. These themes could be explored not just through romantic connection but platonic, sexual or even societal connections too. It just so happened that a work like Cloud Atlas approached this through the lens of a love story, and that it was well executed.

That’s the thing with things are complete opposites of one another. Cloud Atlas does stand in contrast to The Visitors and The Lovers, but I think that actually helps to create a really strong, unbreakable bond between these three works. When you look at the Chinese zodiac, it is usually visualised in a wheel. It is said the most compatible signs are the ones that sit across from each other. It’s the same with something like the colour wheel as well. Colours that sit across from each other are actually the most complementary. So I don’t really think the three works I selected are all that different from each other. I think the contrasts between them draw these works closer to each other in a very intrinsic and connected way.

I only realised the importance of passing time to my practice about two years into working with needlework. I’m actually a rather impatient person. I get frustrated waiting in line. If a bus takes too long to come, I’ll just walk to the next stop. I hate waiting. Yet, I can sit down on a chair and sew for ten hours straight. It doesn’t make sense. For 22 Years of Thickskin, I was interested in unravelling myself from internalised racism. My work has always been interested in microaggressions, and this is mostly due to my background. I grew up in a Chinese family and my dad is an immigrant Indian. Growing up in a predominantly Singaporean Chinese household has played a huge part in me internalising microaggressions and racist attitudes towards my Indian blood, heritage and culture. When someone makes an offensive joke, I am often told to not be so sensitive or be more thick-skinned. 22 Years of Thickskin was essentially my way of unravelling from that fog.

There actually isn’t that much thread involved in 22 Years of Thickskin. I made it whilst I was on a remote farm, and we didn’t have phone or internet connection there. I’d spend hours writing page after page, and soon there was a narrative that connected these words. If you want to consider this episode of automatic writing on a farm as an act of documenting the passing of time, you can. I turned 22 when I made that work, hence the title; and I was desperately trying to get out of this skin that I had created for myself. I didn’t make it with the intention of visualising passing time, but now in hindsight, it does.

² 22 Years of Thickskin, Nature Shankar

2018

2018

There are multiple facets to 22 Years of Thickskin as well. We can talk about how the work discusses issues of race, the relationship between text and thread, or how you brought in notions of a physical body by referencing skin. With a work that is laden with visual and personal meaning, what drew you towards using and evoking layers to communicate these concepts?

I’m really happy with the title for that artwork.

I had been playing around with the word “thickskin” in my mind for a couple of years, but never had the artwork for it.

I even found myself forcing it onto particular works. When I completed this one, it just made sense and everything fell into place.

³ “Untitled" (Perfect Lovers), Felix Gonzalez-Torres

The Museum of Modern Art, 1991

⁴ The Visitors, Ragnar Kjartansson

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and Gund Gallery, 2012

Let’s talk about the other works you selected for this interview. You spoke about when you first watched the film Cloud Atlas previously. Could you tell us more about when you first encountered The Visitors and The Lovers?

I encountered Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work whilst I was still in school. It was a long time ago, and I remember that the lesson was on readymades. When I first saw it, I didn’t really get all the fuss around the work. It is, after all, just two clocks. The context and the concept surrounding the work wasn’t actually covered in class, so I had to do my own research to find out what the work was really about. When I read the artwork description, I started sobbing. The artist starts the two clocks at the same time. Over time, the two clocks will fall out of sync with each other. Eventually, the battery in one clock will fail as the other ticks on. This work mimicked the artist’s own life, as his lover passed away before him as well. It was the first time I experienced such an emotional response to an artwork, and that’s why I always come back to it. The description for the artwork was so simple, but it managed to affect me deeply.

Prior to starting school at NAFA, I had no background in the arts or art education. The curriculum at NAFA places a heavy emphasis on technical proficiency and skills, and I’m very thankful for this focus on the medium. Yet it is also important to know that art is so much more than painting the flower you see in front of you. Encountering Gonzalez-Torres’ work opened my eyes and my mind towards how expansive art could truly be.

I chanced upon The Visitors by pure luck when I was in San Francisco with my father. He had a bunch of meetings, and so I took myself to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). I was tired after walking around for the entire day, and found myself on the top floor of the museum. When I saw that the space was exhibiting yet another new media work, I was actually ready to dismiss it entirely. I walked into the space, and all nine panels started lighting up slowly. The musicians in the video started to play, and the entire work runs for 64 minutes. I sat there for three hours. There was a couple who were viewing the work with me, but started slow dancing to the music. It was such an experience that I Facetimed my partner at the time to show him the work.

As I entered the art scene and began to take my practice seriously, it became clear to me that art is a business. That realisation can be rather draining, and when that happens, I sometimes find myself approaching art making in a rather methodological manner. Framed works sell better, for example. When I catch myself descending into that spiral, I’ll think about these three works.

It sounds like all these works function as a centering force for you. Aside from this, you take a long time to produce your own works as well. You spoke earlier of sitting down for ten hours straight just to sew. Do you think that the slowness of your medium has also helped you deal with the cacophony of the art world?

Oh, definitely. The first time I worked with embroidery was with Roots To Existence, and that’s when I noticed the power of the medium. As I was sewing, things that I had forgotten for awhile started flowing back to me. I made the work for my final year project at school. For some reason, I didn’t feel like painting so I picked up a needle.

That was also the first work in which I used the phrase “我是小黑" (I am Little Black). “小黑” (Little Black) was my childhood nickname, and only my grandfather would call me that. Prior to making that work, he had passed for about five years. I was experimenting with the needle and thread, and these memories came flooding back to me. From then on, everything just moved naturally. Sewing and embroidery definitely possesses the power to recenter myself, but beyond that, it also helps me create a cocoon within which I can think clearly.

Let’s talk about the phrase “我是小黑" (I am Little Black), because it recurs across a couple of your works. Many artists use repetition within their practice, but they all have their own unique way of wielding this device. This is a very, to put it lightly, charged phrase that carries incredibly personal memories for you. How have you used repetition as a device to navigate, process and unravel these conflicting emotions?

With an installation that I did, SOMEWHERE ALONG THE LINE(S), I worked in a room with false walls. I just keep writing the phrase “我是小黑" (I am Little Black) over and over again across the walls. For a long time, I was told not to revisit that phrase because of how painful it was. Suffice to say, suppressing or ignoring it did not work. It was only after being in my cocoon and working through these experiences that I realised that dealing with the term head on was the only way forward. I felt so disconnected from the phrase, and it was only after filling the walls of an entire room with the term that I was able to arrive at yet another layer of meaning — taking back power.

⁵ Roots To Existence, Nature Shankar

2016

2016

You’ve spoken before about the difference between sewing by hand and using a sewing machine. Could you elaborate on why you prefer sewing by hand, and what it means to you?

I find that using a sewing machine actually gets in the way of my expression. When I use a machine, it doesn’t feel like an extension of myself or an extension of my arm. There are people who consider a machine to be an extension of their own body, but that’s not the case for myself. There is something about holding the cloth in your own hands, and passing a needle through it consciously. I’m not feeding the cloth into a machine, but I’m feeding it through me. There is an intimacy with sewing by hand that I don’t get when I’m working with a sewing machine. It’d be so much easier for me if I used a machine, because it would make the process of working so much faster for me. But somehow I can’t help but feel that machine-made works lose their element of pathos.

We always think of sewing as the act of decorating, or of joining two cloths together. In fact, sewing actually involves piercing the cloth with a needle. Sewing is destructive. It leaves scars, and it changes the cloth. In particular, the textiles I use in my works are gifts from my grandmother. I’ll never be able to purchase them again. When I cut these cloths up for my work, I do feel a keen sense of responsibility. I can’t just bulldoze my way through. I have to think about every step. Why am I cutting this cloth up? What do I want to achieve with this?

In some twisted way, I think I can only make work through this process of reckoning and through this rite of passage.

My works cover incredibly personal topics. I have to go through internal turmoil with myself before realising how that plays out on a larger scale, where these struggles have resonances beyond just myself. I think that in dealing with such intense topics, we have to meet them where they are at. We have to grapple with them with equal intensity.

Although this perspective has shifted drastically in recent decades, many still associate needlework and embroidery with femininity and the domestic sphere. As someone who works closely with this medium, why were you drawn towards with needle and thread and how has your relationship with the medium changed over time?

When I exhibit my works, I often hear remarks from viewers that go, “I saw your work, and I immediately knew that it was made by a woman”. It’s not a great response, and that’s not because I’m insulted. It makes me wonder why people immediately make the association between a work and an artist’s gender. It’s 2019.

Linking embroidery to domestic work is an outdated notion, especially because it has historically been an incredibly powerful medium.

For example, needlework was incredibly important to the women’s suffrage. Embroidered banners were a prominent feature during these marches, and they were a way for these women to make their voices heard on their own terms. The suffrage movement went on to make significant strides in the fight for gender equality. We fall back on blanket statements or sweeping generalisations because we forget this history.

I actually wrote my dissertation on the notion of needlework and embroidery as craft. I don’t see needlework and embroidery as a craft anymore, but my practice has developed quite a lot. It grew from a place of seeing needlework as craft, but I see many other mediums as crafts as well. Painting is a craft. Making digital works is a craft. As an artist, you always have to master the technicalities of every medium before you can use it to fully express yourself.

I’ve also been thinking about what the difference between the handmade sari I have at home and the garment that sits behind a museum’s glass display case is. There are a lot of museums around the world who display traditional works as art. On the one hand, these objects are art and should be treated as such. Yet, who gains from the display of these works? Do these communities benefit in any way by having their works included in these institutions?

There is a clear distinction between the fine arts and craft or design, and it is evident in how some museums are organised today. Even when textiles make their way into a museum’s collection, the artist is usually unnamed or unknown. This stands in contrast to painted works or sculpture, which often bears the signature of its artist. It raises interesting questions about authorship and how an artist is inserted into her or his work across varying mediums.

I’ve always found the categorisations or arrangements at museums fascinating because in my experience, nothing fits neatly into a single category. Something can be good and bad at the same time.

⁶ SOMEWHERE ALONG THE LINE(S), Nature Shankar

2017

2017

You work primarily with textiles and needlework, but have incorporated texts and drawing into your pieces as well. In particular, the work you exhibited at SAFESPACE(S) featured multiple elements that were sometimes layered on top of one another. As a result of the overlapping material, not everything is visible to the viewer. What did you intend to achieve through this act of collecting and collaging?

I don’t think I have a particular intention in mind. My works are often very layered, and it often is a result of prolonged negotiations with myself. The more rigid side of me will start to arrange the different materials in a particular manner, but there are times where I just let the process happen. When it comes to intention, I think I go through phases. There are moments when I’m making a work where I think that I need to attach a particular meaning to something, and there are also moments that I don’t. It just is a constant cycle that repeats itself until the dust settles a little and I’m happy with the work I’ve made.

Let’s talk about the experience you made with OH! Open House earlier this year. You invited the audiences to bring along an object of personal significance, and the whole experience was a meditative and almost therapeutic one. As an artist, you poised yourself to meet the audiences half way. I understand that you crafted this work in collaboration with the hosts and the curators, but could you tell us more about the process behind putting this together? Was it difficult accounting for the fact that every viewer would have a different response?

We were more concerned with how to get the participants comfortable in the space, and how to deal with participants who might not be ready to share so freely. There were questions around the technicality of the entire session as well. The experience started with us offering the participants food. The hosts and myself are all from different parts of the world. We wanted start by talking about the sort of things we wanted to keep. We introduced the participants to the sort of food that we’ve keep with us throughout our lives. Ganesh had buttermilk, Pei Ying had a recipe for Belgian waffles from her aunt, Lisa offered bread, Ryan chose banana chips and I brought butter cookies. After we had some food, we did a short workshop together where I introduced participants to the process. The guests were each give a ball of yarn, and every ball was a different shade of grey. They were invited to wind the piece of yarn around the objects, and to bind them up. Finally, the participants were invited into a one-on-one session with me in the back room. I wasn’t there to tell them what to do or to give them advice. We’d just sit together and do word association. I’d always end with asking them about the purpose of their visit. Some participants gave very intriguing answers that you could see reflected in the object they brought to the session, and that was very rewarding for me.

This was my first time crafting an experience and performing, so I think it went as well as it could have gone. Evidently, not everyone met us halfway; but for those who did, the results were so enriching.

When I conceptualised this session, I wanted it to be a time where participants could feel the weights lifted off their shoulders and be at peace.

⁷ Passport: Nature Shankar × Pei Ying, Nature Shankar

2019, Installation View for OH! Open House

2019, Installation View for OH! Open House

You have also stepped into the role of being a curator, and we touched on an exhibition you curated last year titled SAFESPACE(S). Tell us more about the show, and how your work as an artist informs or is kept separate from your curatorial work.

I think it is very important for an artist-curator to separate the two roles from each other. I realised this when I was working on SAFESPACE(S). If you go into curating with an artist’s perspective, the show becomes your artwork. When you’re working on an exhibition that features the work of multiple artists, you need to be cognisant of the fact that you’re not making work. You’re creating a space for other artists to display their artworks.

When I’m curating, I don’t have to recenter myself with those three artworks we spoke about earlier.

I don’t have to be poetic as a curator, it’s not my job to be poetic. Instead, I have to help the artists realise the poetry in their own artworks.

If a curator doesn’t recognise the difference between curating and being an artist, it will jeopardise the artists who end up exhibiting with them.

Last year, you spent a significant amount of time in New York City doing a residency and an internship. Was that experience of being plugged into a different artistic ecosystem and culture formative for you? If so, how?

By pure coincidence, Ragnar Kjartansson was giving a talk at the New Museum whilst I was in town. The talk was sold out, but I was lucky enough to be let in when I showed up at the door. When I was in New York, I didn’t have to run through the three artworks to recenter myself because I was going to all of these events and listening on all of these talks. I can’t explain it, but you definitely feel a lot freer in New York. I think the time I spent in New York really helped solidify some of the previously half-baked thoughts I had towards approaching my practice. I don’t want to end up creating works that are solipsistic. If your work is not for the people, then who is your work for?

New York is always changing, the ecosystem is a vine that never ends. In Singapore, the ecosystem is a bit of a loop. I think that’s the key difference between the two cities. In the United States, especially in somewhere like New York City, they are very aware of what’s going on around them. In Singapore, we have the luxury of avoidance. We can close our eyes here and racism disappears, but that’s not really an option in New York.

Having said that, I’ve enjoyed quite a few of the exhibitions I’ve seen here in Singapore. I’m really excited to see how the scene develops here. I’m not one to comment, because I’m just a spectator. I’m not a curator in an arts institution, instigating a movement or initiating conversations. There is a momentum that’s being built up here, and it’s exciting to be hearing from different people.

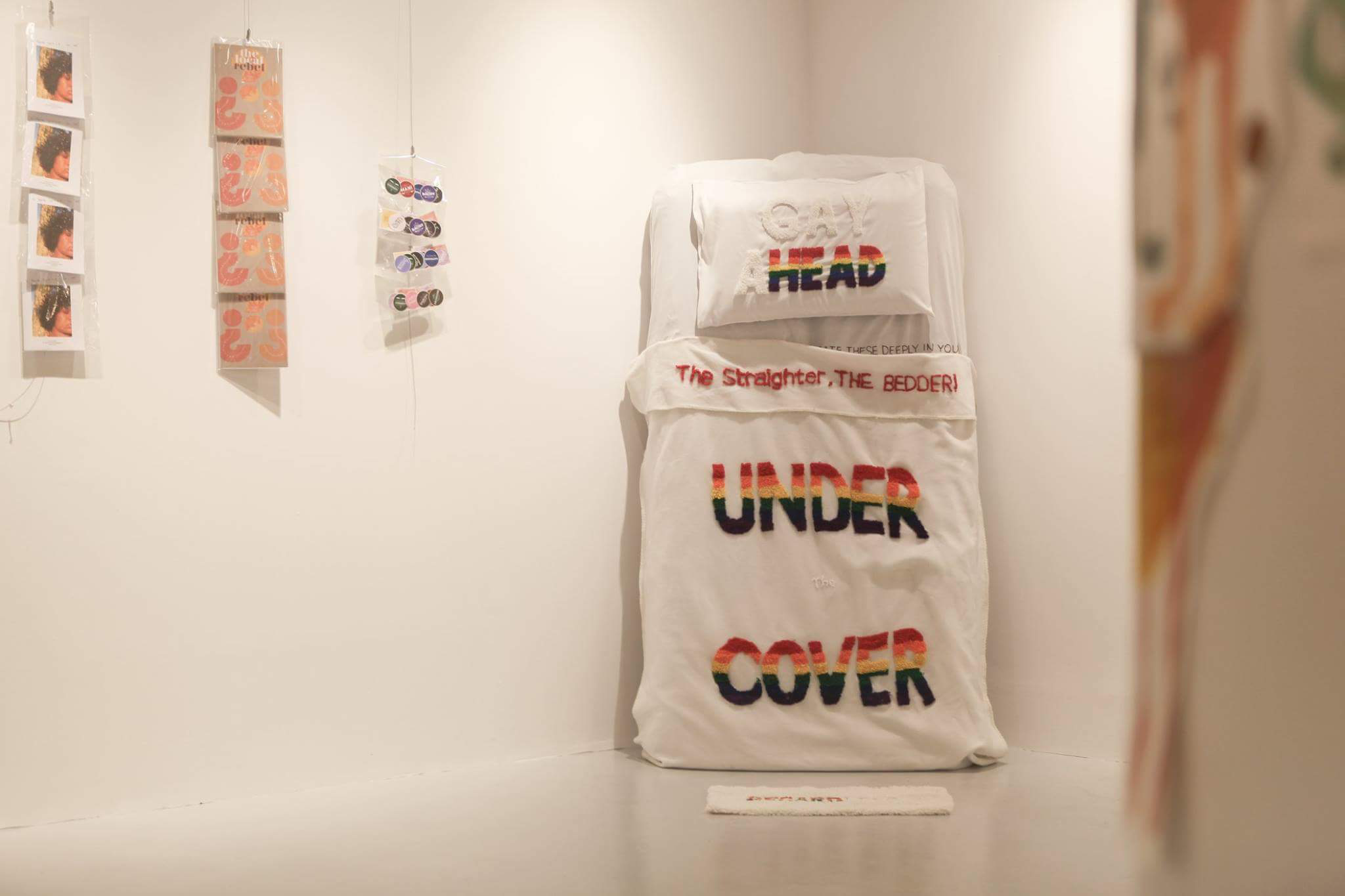

⁸ SAFESPACE(S)

Installation View at The Art Space by Natalie Wong

Installation View at The Art Space by Natalie Wong

Your work has always come from a very personal place. Moving forward, how do you see yourself striking that balance between working as a confessional artist and not making the work all about you?

I’m still trying to figure it out. With some of my previous works, I stumbled onto the right balance by sheer luck. In and of itself, an artwork is a system. It can grow organically from a single point, but it then gains multiple points of departure and becomes increasingly layered.

I’m working towards a place where it begins from a personal memory but expands to then cover topics that go beyond just me, myself and I. A work could begin with a painful experience, comment on racism, then further encompass the feeling of yearning. I think yearning is very important, and it is a universal feeling. One could feel incredibly thirsty for a glass of water — everyone knows that feeling. I’m still trying to figure out the exact balance, and I think a lot of other people are too.