Slow

Conversations

Nawin Nuthong is a Thai contemporary artist and curator exploring the connections between history and cultural media through a wide range of mediums. Melding myths and legends with pop-cultural references from video games, comics, and film, he examines the role technology has to play in reconfiguring the learning and understanding of history. He is a graduate from King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang with a major in film studies and digital media. His recent presentations with Bangkok CityCity Gallery include, THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS (2020), A room, where they are COEVALs [Precise at a dig site door] (2021), and Heaven Crumbles: The Marvellous Misadventures of Sudsakorn (2021). Nawin also participated in the 2022 edition of the Bangkok Art Biennale: CHAOS : CALM.

Filed under: animation, archaeology, found objects, graphic design, installations, internet art

¹ Kra-bi (กระบี่) and krabong (กระบอง). The wooden weapons are used in traditional performances, but this particular krabong design may also be found in the context of a religious altar at home.

For our

conversation, you’ve picked out a series of five objects and when you shared

them with me, you were concerned that they were references that may be “too

Thai”. At the same time, it seems like many of these objects or materials can

be seen as building blocks towards an imagination of “Thai-ness”—as vague or

contested that may be. Do you see these objects as being connected by an overarching

narrative, or as individual entities that intrigue you for different reasons?

I was working on Aleaf for the recent Bangkok Art Biennale, and have been thinking about it over and over again. The Thai context is central to a work like Aleaf, and I had asked myself if Aleaf was too “Thai” as well. I worked with a team to put Aleaf together—some thought that the references were too traditional, and others thought that they were not Thai enough. The objects that I have picked out for this interview reflect those discussions.

To your point on “Thai-ness”, I think it is an important question within my practice as well. I am interested in how we are going to understand these governing systems with live under, which tries to balance democracy with the reigning monarchy. I want to dig through history, and I want to understand things more. I’ve been thinking about these topics in relation to map making and gaming a lot.

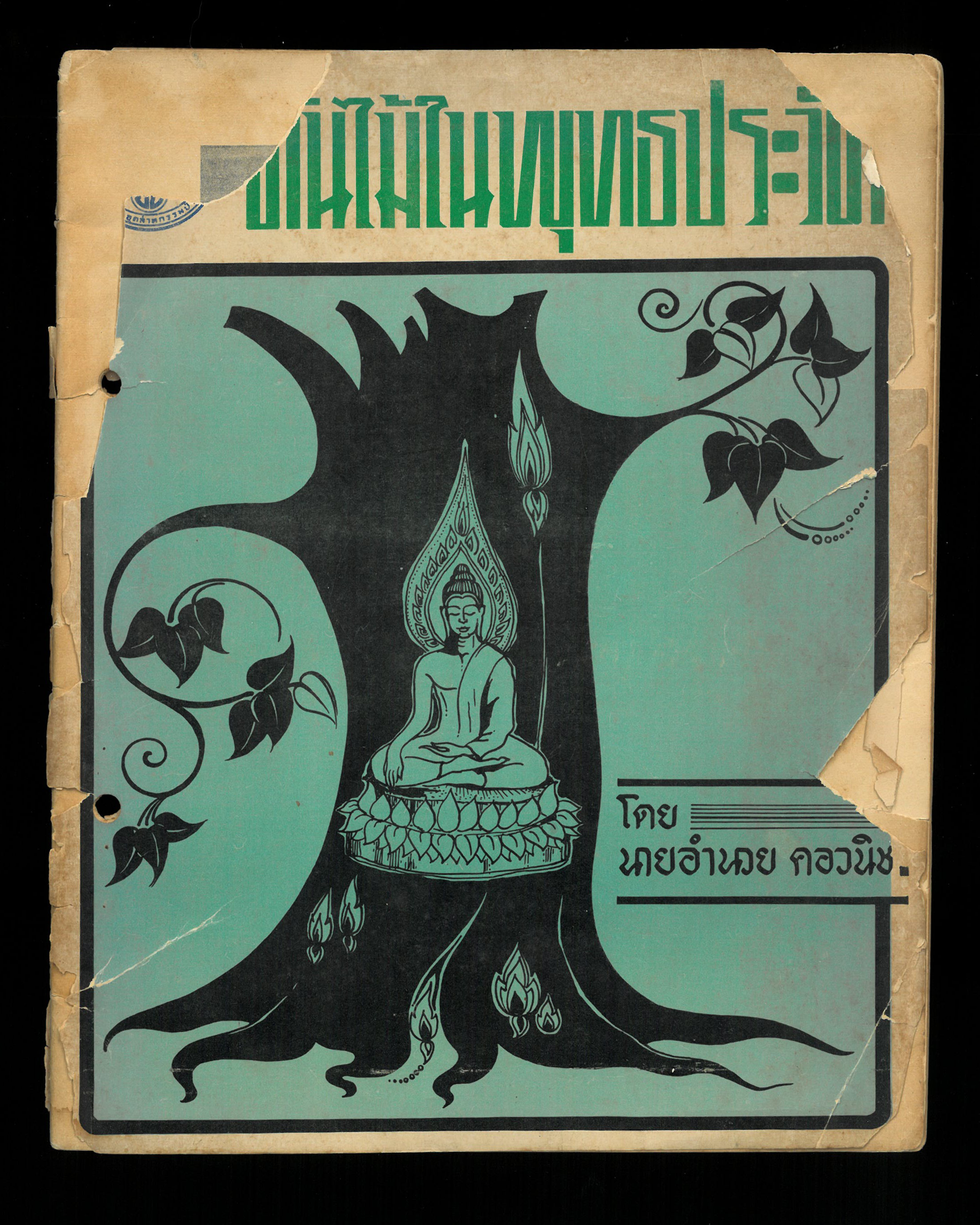

² Trees in Buddha’s Biography (ต้นไม้ในพุทธประวัติ), Amunuay Korwanich (อำนวย คอวนิช)

1970

Could you expand on some of the

conversations you had with your team when making Aleaf? It sounds like

these discussions were very interesting and dynamic, and I was wondering if

there were discussions that you remember as being more significant?

It might be awkward to discuss this now, but back in the day, I studied communications design and animation. I am surrounded by graphic designers and animators, and we learnt quite early on that a direct portrayal is not always necessary in telling a story. For Aleaf, some of my team members had a fine arts background. I wanted to set up the work as a conceptual yet contemporary object, and as the author, it made a lot of sense to me. At the same time, I’m always conscious of how I’m communicating these ideas to my team and to the viewer. I’m careful with how content channels are placed—what I call the traffic light of questions. Aleaf started with an interest in “Thai-ness”, but it might not be the most traditional interpretation of that idea. I don’t always know where I’m going with my research, so it’s also helpful when my co-creators tell me that something is not working or if something is too much.

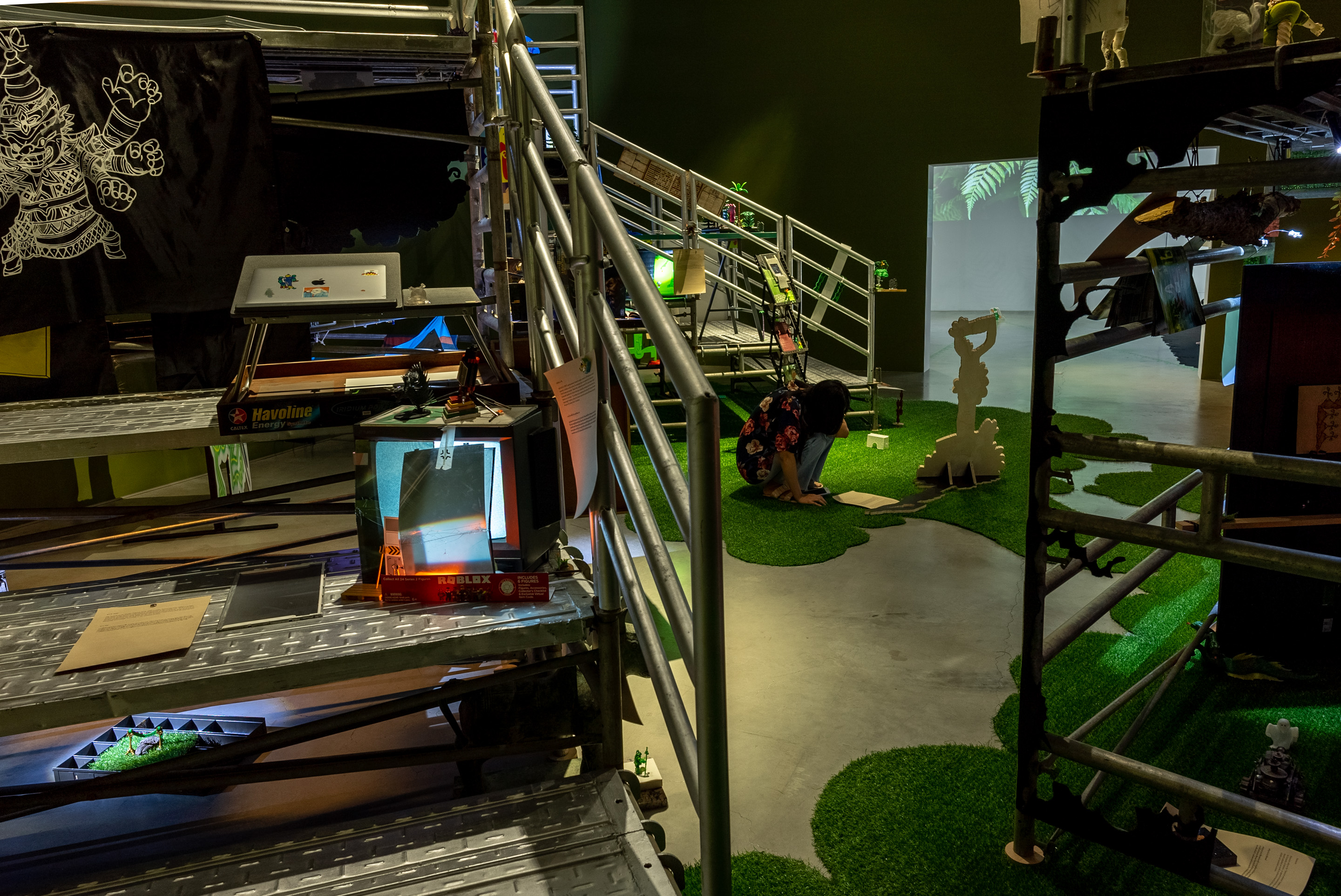

³

Aleaf, Nawin Nuthong

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

⁴ Aleaf, Nawin Nuthong

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

Credit: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

⁴ Aleaf, Nawin Nuthong

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

Credit: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai

⁵ Bookshelf block from Minecraft

It sounds like a large part of the

process for you is also trying to make sense of these various layers, and what

to focus on in the context of a single project. Some of the objects you’ve

picked out today are quite key to projects such as THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE

BUSY THESE DAYS, where you maintain a website dedicated to these objects

and their “management”. Could you elaborate on why you decided to describe the

process as one of “management” as compared to that of organisation or

selection? These terms are not too far off in terms of their meaning, but

“management” in particular suggests slightly different connotations, so I’d be

interested in learning if you had that intention in mind when using such

language.

I thought about the word “management” a lot. I’m not sure if I’m using the right word here, but dealing with objects is my passion. I try to design installations in a way that might help people understand how I’m exploring an issue. I’ve been looking at these objects for a long time before I had the opportunity to work on this exhibition. There were so many objects that I was referencing in this project, and I wanted to arrange them in a very spontaneous way.

I first met Kritti Tantasith at Ghost:2561, and we continued working together at Speedy Grandma. We both play a lot of games and learn a lot from one another as well. A lot of our conversations revolve around how a game is designed and its interface. Together, we looked at the objects I had been collecting and he began deconstructing many of them. We actually argued about using the word “management” a bit. However, the more we worked with these objects, the more complex this undertaking became, and we wanted to give this sense of how data expands. We also wanted to relook these objects again and again and thought of this iteration as the first chapter in a longer-term project. This was why we thought to use the term “management”.

Looking at some of the projects that

you're working on, diagrams and systems seem to be quite important. It’s also

interesting that you talk about data as something that constantly expands,

because this sort of research, cataloguing, and arranging could go on

forever—but it’s also often important to think about how manageable a project is.

Working on THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS actually led me towards constructing the word “archaeogaming”. The title of the show focuses on the spiritual. By collecting all these objects, my interest wasn’t in these gods per se, but how the aesthetic of their icons has changed over time. With the title, I imagined the gods to be busy morphing into a new visual icon. I don’t think I’m done with the work’s form yet, but I’m incredibly interested in the constellation that formed around it—from production to the relational dynamic, and even to the virtual.

By collecting all these objects, my interest wasn’t in these gods per se, but how the aesthetic of their icons has changed over time. With the title, I imagined the gods to be busy morphing into a new visual icon.

Speaking of THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE

BUSY THESE DAYS, the work was first installed at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

in 2021. The website we talked about in the previous question demonstrates and

organises much of the research that you have been doing. Could you tell us

about how you see the physical iteration of the project in relation to its

digital counterparts? Were the two developed concurrently, or did one emerge

after the other in support?

I worked on them at the same time. I have collected so many stories over time, and I really want to understand them—though not all at the same time. I wanted to place them all in one place so that I could exercise these ideas again and again. I didn’t design or plan for the website to run forever, or even for this long. But I’m still using the website, even today, to understand the objects that I’ve collected.

I remember thinking that people in the installation might want to come back to these ideas after seeing the show. Some people also do not have the time to spend half a day in the exhibition, so this site was built with these visitors in mind. Instead of leaving visitors with photographs of the installation view, the website allows them to explore the funkiness of the installation in virtual space.

⁶ THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS, Nawin Nuthong 2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

⁷ THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS, Nawin Nuthong 2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

⁷ THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS, Nawin Nuthong 2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

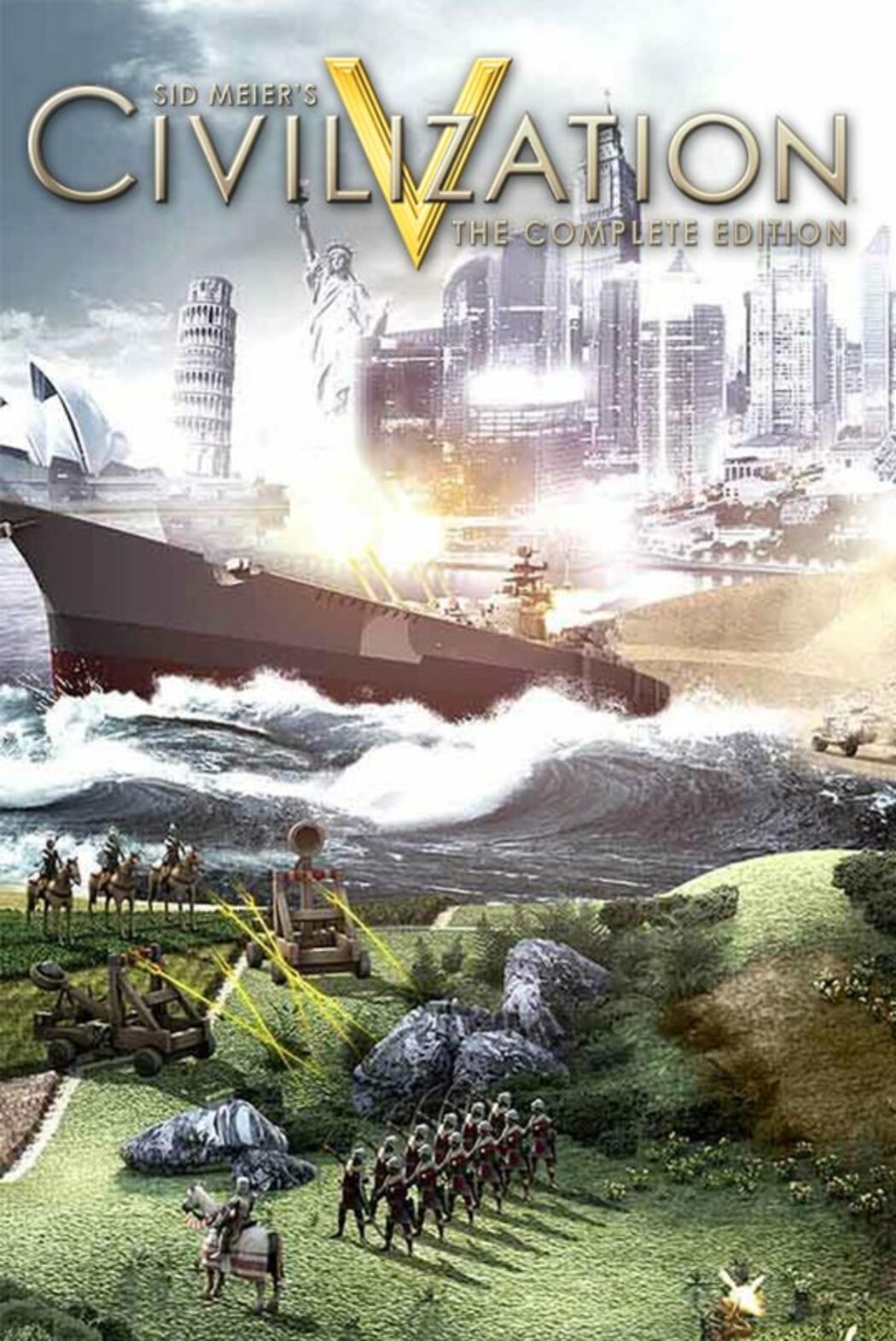

⁸ Civilization V, 2010, developed by Firaxis Games

⁹ Sagat Thai Guardian Set, produced to either be presented alone or to accompany the action figurine of Street Fighter character Sagat.

There is a very clear interest in

archaeology that underlies recent projects of yours, such as Aleaf. At

the same time, the work does not present archaeology as a rigid discipline that

deals squarely with antiquated artefacts. It is reimagined as a game, a

technological tool or a site of construction. Could you elaborate on how you

think about the relationship between archaeology and the realm of speculation?

Why approach archaeology as a theoretical or hypothetical exercise at all?

I respect sociological and anthropological work a lot. When I was developing Aleaf, “archaeogaming” became a helpful way for me to describe to others what my work was about. I love the word “archaeogaming”. It’s not a solid word. I also like the concept of excavation, and the ground as a thematic. In games, the ground is often the thing that players want to but will find difficult to dig into when finding treasure. In gaming communities, archaeogaming may refer to the overarching mythology or narrative of the game, or the act of finding easter eggs in a game. Some take this concept one step further by hanging into the game’s code itself or tracking the development team’s glitches in order to foresee what happens next in the game.

There are also a lot of games themed around artefact or treasure-hunting, and there’s often a fictional story that underlies the entire game. One example of this is the figure of Ramkhamhaeng in Civilization V, which I also picked out for this conversation. Ramkhamhaeng is an ancient Thai king, and his image is considered sacred. As such, the developers of the game decided to use Thaksin’s face for the character instead. There are so many conflicting things that are layered onto each other here, and that’s how I composed the word “archaeogaming”. I started with research, and when I couldn’t go any further with that research, I used other tools such as fictional characters. This is why THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS starts with a child talking to a tree and expressing that he wishes to understand history.

I have an interest in the practice of archaeology, but on the other hand, I’m also looking into cultural heritage right now. I can go to introductory classes about history, but what I really want to understand is what I call dinner table history. One way to explain what I mean by dinner table history is to use the analogy of a family dinner where the father gets into a heated argument with his daughter. At some point, the argument dies down because the father has had the last say. But his son, who has just finished up his game, is coming out of his room and sits at the dinner table. The argument is picked up once again, but this time, the son has the last say. Everyone at the table has a different line of reasoning, and they present their own version of the story. I really believe that these multiple versions are the most reflective of how most people think about political matters, for example.

I’m from Phuket, and I grew up around expats. The school that I attended taught classes in English, and I remember an Australian teacher taking us to a field trip to Kanchanaburi, which is a significant World War II site. That was when we found out that our teacher’s father had gone through a very horrific ordeal during the war. This anecdote also sums up what I mean by dinner table history.

Everyone at the table has a different line of reasoning, and they present their own version of the story. I really believe that these multiple versions are the most reflective of how most people think about political matters, for example.

This tendency to collect or listen to

little or smaller histories is reflected in installations such as Aleaf.

Your works are all encompassing environments: objects, references and materials

are layered one above another to create a dense, full-bodied experience. There

is a sense that the space is one of organised chaos, and I was wondering if

there were any aesthetic principles or references that guide the way in which

you compose these installations? Do you work towards achieving a certain visual

quality in making these works?

I’ve been asked this question a lot, but I always answer it differently. Let me try to connect these various answers into one for you. Instead of visiting national parks or outdoor spaces, a lot of Thai children grow up going to large, indoor shopping malls. These malls often have a playground on the top floor where children can play, and they can be themed as well. There are two generations now that have grown up with these playgrounds as public space. We play games such as hide and seek in these playgrounds, and it influences how we understand space and learn how to play with one another. Some of the aesthetic in my work reference these playgrounds.

I also started to expand my own research into how we tell stories because I love world building. I talk to P’Op, Akapol Op Sudasna, the owner of Bangkok CityCity Gallery, about film making a lot. He makes films too, so we spend a lot of time discussing the pre-production or conceptual phase with one another. Before you build Middle Earth for The Lord of the Rings, you need to produce hundreds and hundreds of sketches. You need to think about Tolkein’s own context, and the backdrop of World War I. I’m interested in this process of sketching thousands of Gandalfs, for example, before the director settles on the right one.

I don’t think I would call myself a film maker, but I would say that I love the idea of dramatic need. In A room, where they are COEVALs, I placed some objects directly across from one another. I sited the white room in the work on Bhumibol Dam because I was interested in the conjunction of the Cold War with terraforming projects in Thailand, for example.

¹⁰ Aleaf, Nawin Nuthong

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

¹¹ Aleaf, Nawin Nuthong

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

Credit: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

¹¹ Aleaf, Nawin Nuthong

2022, Installation View at Bangkok Art & Culture Centre

Credit: Preecha Pattaraumpornchai

Continuing the previous question around

your installations as embodied experiences, they function almost as sets that

audiences enter. In doing so, they are not neutral parties, but characters who

are very much enveloped into the world that you’ve built. Is it important for

you that a viewer experiences a different world or conception of time within

your installation?

I think this might be most evident in Aleaf. Aleaf started from that image of the single running horse, and that’s how I always work. That might make me a bad curator because I already have a clear form in mind. The question of time is a tricky one for me, because it’s always tied to Marxist theory. I understand Marxism, but I think my own background has given me a different perspective because I grew up in a factory. I also see the running horse as a metaphor for Rattanakosin, the Kingdom of Thailand, which might be why Aleaf is quite focused on the question of time.

However, if you’re asking me whether I knew it would turn out this way, the answer is no. When I make installations, it’s quite process driven. The curator of Bangkok Art Biennale told me, “Tan, you need to be Marvel. Push out the multiverse and that kind of knowledge.” So, I started developing the work with the research I was doing, but I never stopped the research process. There was so much I wanted to put into the work, but you will see a black dots and crows everywhere in the installation—they all point towards this sort of storytelling that I hope I can push further in the future.

Given my background in graphic designer, my instinct was that the storytelling element of the installation might not be very effective. But it turned out well, and I’m very happy with it. I keep trying to reinvent myself, and I keep telling myself not to run away from the white cube space by doing virtual projects because there are still lessons that I can learn from the white cube context.

It’s quite clear that you don’t feel

like you’re done with the projects that you’ve started on, which mean that many

of your projects are long-term engagements that run on for several years and

unfold across various permutations. There are many reasons why artists work on

multi-year projects, and I was wondering if you could tell us a bit more about

your own reasons for doing so. Why do you find yourself gravitating towards

working in this way?

I’ve only been practicing full time as an artist for about two years. I don’t know the future, but after finishing Aleaf, I know that the three projects that I’ve been working on are archaeology sites. They are markers of evidence, and they also present the sketches for how I got here.

I’ve been told by a close collaborator, Podcharakrit To-im, that THE IMMORTALS ARE QUITE BUSY THESE DAYS is about archaeogaming, A room, where they are COEVALs is about coevalness, and Aleaf is about chronocentrism—but I think it all happened organically. With all my projects, I’m trying to understand the building blocks of how we’re connected. As I said earlier, I’m looking into cultural heritage now. This fits into A room, where they are COEVALs, although everything is linked to one another. When I talk about a childhood memory, or the idea of excavation, or even a drawing I’ve made, they are all connected in some way.

With all my projects, I’m trying to understand the building blocks of how we’re connected.

¹² A room, where they are COEVALs, Nawin Nuthong

2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

¹³ A room, where they are COEVALs, Nawin Nuthong

2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

¹³ A room, where they are COEVALs, Nawin Nuthong

2021, Installation View at Bangkok CityCity Gallery

Though art making constitutes a large

part of your practice, you also have an active interest in curating and

organising as well. Could you expand a bit on this aspect, including your work

with Speedy Grandma, and how it informs the way you approach art making now?

I think I’m always asking questions and trying to push things further. When I was young, I was always skeptical as to why I had to pray to the Buddha, for example. I was always very scared of hell. When I watched Aladdin, I knew that if I ever met the Genie, all three of my wishes would be spent on wishing that I won’t have to go the hell. When I went to a Christian school when I was older, I committed to the religion because I was told that if I did so, I would go to heaven. At the same time, I grew up in a province where I had Muslim neighbours and colleagues. It got me wondering: why can’t they go to heaven too? I started thinking of different ways around the problem. I tell this story to illustrate how this one thing can develop—all because one child did not want to go to hell. I also think my high school education prepared me to deal with data and raw knowledge, and how to analyse this information.

With my art practice, I’ve been drawing for a long time. When I was young, I was very proud of the fact that I could draw. I would not know how to turn on the TV, but I would be able to draw quite well. It’s been eight years since I started working in the arts. I was introduced to curating when I was in university, and in it, I saw the possibility of making the job my own. I enjoy developing the works of my friends, and I learn a lot in the process of doing so. That was also when I got involved with Speedy Grandma. It was founded by Unchalee Anantawat and Thomas Menard. At that point in time, we had a real problem with gatekeepers in the Thai art ecosystem. There were new graduates who were returning to Thailand after spending some time away, but they did not have much space to express themselves, so Speedy Grandma became an important space. I started interning there about four years after they were established. There, I learnt a lot about installing works and met a lot of different people. I was lucky to have had that chance, and the time I spent there really fed my curiosity.

I’m still curating and organizing now because I want to create exhibitions that place the artefact next to the conceptual, and in conversation with the artist—spaces where you can bounce questions around. I’m working with Bangkok CityCity Gallery now as well. Beyond working as a practicing artist, management, organising, and curating helps to satisfy my own curiosity.

The political situation in Thailand now is also confusing, and everyone’s struggling with it. Speedy Grandma and Bangkok CityCity Gallery respond to this context differently. If there are protests, people might gather at Speedy Grandma after. During the Covid pandemic, Lee and her friends collected medicine, pulse oximeters, and oxygen concentrators, and gave them out to the community. They also helped to connect patients to the right emergency hotlines. Bangkok CityCity Gallery organizes programmes and exhibitions that go beyond the perimeters of contemporary art to be in dialogue with other creative industries such as design and architecture. In doing so, they reach a larger circle of people, including people who might hold different political views to my own.

I’m still curating and organizing now because I want to create exhibitions that place the artefact next to the conceptual, and in conversation with the artist—spaces where you can bounce questions around.