Organised thematically, the second floor of the Asian Civilisations Museum explores development and localisation of faith and belief systems in Asia. In December 2018, three new galleries were opened to complement this curatorial direction — namely the Christian Art Gallery, the Ancestors and Rituals Gallery, and the Islamic Art Gallery.

Noorashikin binte Zulkifli joined the Asian Civilisations Museum in 2015 as curator of Islamic art. She was lead curator for the revamp of the Islamic Art Gallery (2018), and curated the exhibition ‘Ilm: Science and Imagination in the Islamic World (2016). She was formerly a curator at the Malay Heritage Centre in Kampong Gelam, Singapore’s historic Muslim quarter. She worked on the revamp of its permanent galleries, and curated several exhibitions, including Yang Menulis – They Who Write (2012) and Budi Daya (2015). Her meandering journey includes curatorial and programming positions at National University of Singapore Museum and Singapore Art Museum. She holds a Masters in Interactive Media and Critical Theory from Goldsmiths College (UK). Noora’s current research interests revolve around Islamic Southeast Asia, manuscripts, and the arts of the book.

Noorashikin binte Zulkifli joined the Asian Civilisations Museum in 2015 as curator of Islamic art. She was lead curator for the revamp of the Islamic Art Gallery (2018), and curated the exhibition ‘Ilm: Science and Imagination in the Islamic World (2016). She was formerly a curator at the Malay Heritage Centre in Kampong Gelam, Singapore’s historic Muslim quarter. She worked on the revamp of its permanent galleries, and curated several exhibitions, including Yang Menulis – They Who Write (2012) and Budi Daya (2015). Her meandering journey includes curatorial and programming positions at National University of Singapore Museum and Singapore Art Museum. She holds a Masters in Interactive Media and Critical Theory from Goldsmiths College (UK). Noora’s current research interests revolve around Islamic Southeast Asia, manuscripts, and the arts of the book.

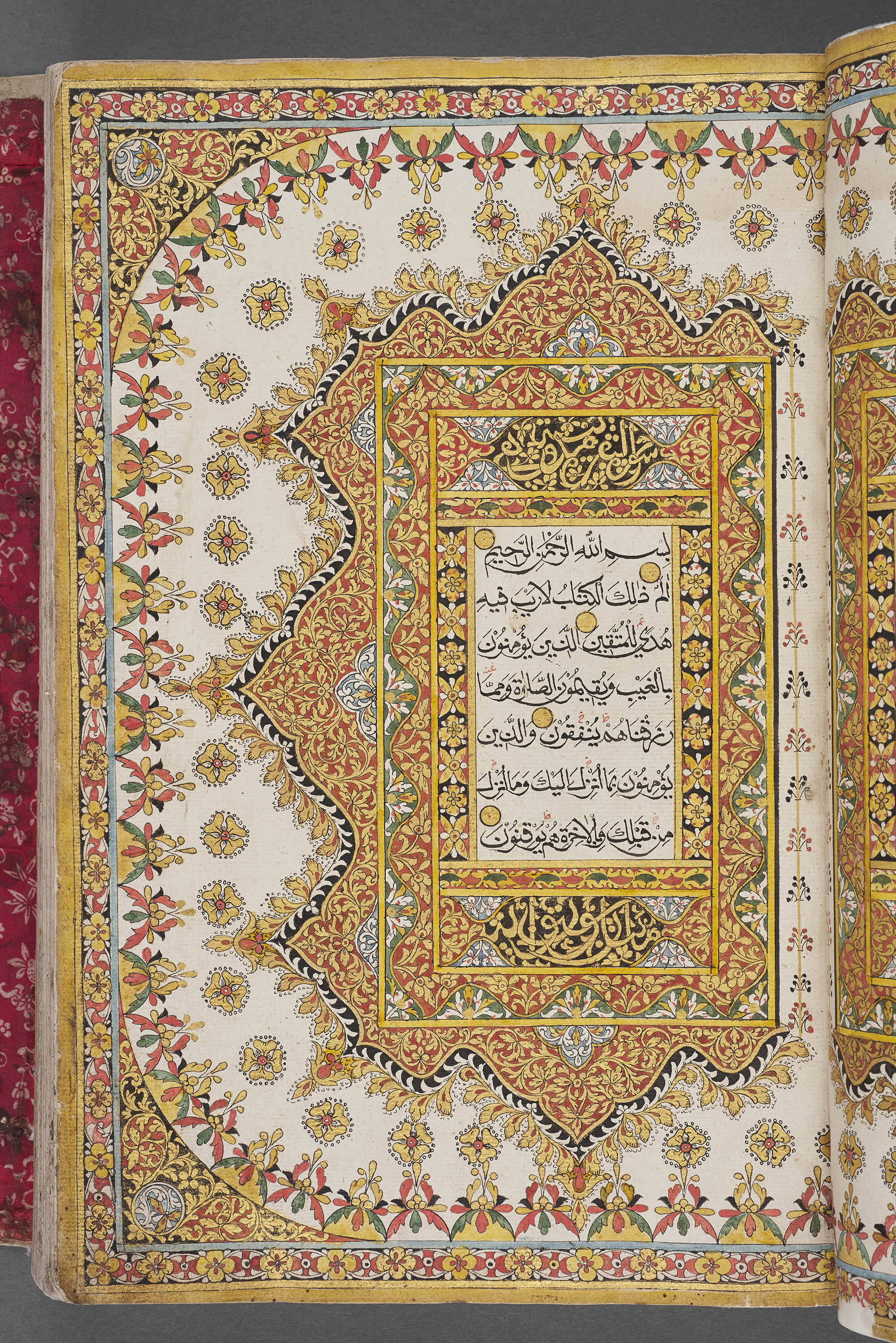

¹ Qur’an

Malay Peninsula, Terengganu, c. 19th century

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

Malay Peninsula, Terengganu, c. 19th century

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

CONTEXT & SIGNIFICANCE

Noorashikin binte Zulkifli (NZ): When we talk about Islamic art, generally, some of the key ideas that tend to come into one’s mind include the arabesque, the importance of geometry, and of course, calligraphy. Calligraphy relates to the significance of script, and its artistic development was keenly felt in Southeast Asia. Because of this, we thought it was important that this Quran was placed in one of the new Islamic Art Gallery’s first few display cases. It is shown alongside a couple of other manuscripts from the region, and highlights how writing influences visual identity — both as a way of associating Southeast Asia with the larger Islamic community, and as a way of establishing regional forms.

Within the context of the Islamic world, the Quran is often the most lavishly embellished and decorated book. When we speak of illumination, which refers to how pages are decorated within a manuscript, the finest examples of illuminated manuscripts are almost always Qurans. Owing to its status as the holy text in Islam, this is a pattern which pretty much holds in the Islamic world and in Southeast Asia.

From this Quran, you can see how interactions with the wider Islamic world influenced its production. It evidences how globalised certain parts of Southeast Asia were, and how certain areas within the region were vying for positions of prominence on the international stage. Elsewhere in the Asian Civilisations Museum, for example in our Tang Shipwreck Gallery, we look at the early interactions between Arab traders and the residents of Maritime Southeast Asia. In terms of Islam, that contact had been established very early on, and what this 19th-century Quran shows is how early local traditions were synthesised with more global or universal Islamic artistic forms. Visually, it constitutes a uniquely regional identity, although there are distinctive styles of artistic production within the region, such as between Acehnese works and Terengganu works.

THE ILLUMINATED QURAN

NZ: In terms of scholarship, there aren’t that many scholars working on Southeast Asian Islamic art. However with regard to the study of manuscripts, we do have a substantial amount of scholarship available, and so far the consensus is that Terengganu was one of the finest schools of manuscript production at the time. The humid weather of the tropics also makes the conservation of manuscripts difficult, and because of this, we conservatively date this Quran back to the 19th century, although there is a possibility that it could have been made slightly earlier.

The Quran itself is a little large in size, and is made in the codex format. This is something that can be attributed to the wider Islamic world, where the book arts were historically made in the codex format. When displaying the Quran, I also made sure that the envelope flap of the manuscript was visible. The envelope flap is a characteristic associated to Islamic manuscripts, and the fabric used for the envelope flap of this particular Quran was probably imported. The fabric contains swastika patterns, and this is where we try to showcase the reality of working artisans in the region. The swastika is a recurring pattern that can be found on a lot of Islamic art of the Southeast Asian region. They would have drawn upon historical tradition, and what was around them at that point in time. One can’t really separate art produced for religious regions from the trade that was happening at that point in time. As a motif the swastika might have Buddhist roots, but it would have been understood as a positive symbol. As such, there would have been nothing wrong with adopting and readapting the symbol towards newer forms of visual art.

When we talk about illumination styles, what we’re looking at are the frames that surround the text blocks. In this particular Quran, we have a frame within a frame, which sits within yet another frame. It makes for a rather dense composition, surrounded by undulating patterns. The scrolling arabesque motif is something that is shared across the Islamic world, but the exact plant portrayed in this pattern was drawn from the artist’s immediate surroundings. In manuscripts made in places such as Damascus, one would see palms or palmettes depicted. However, this Quran features tropical plants that are indigenous to the region.

The colour scheme of this Quran also highlights a feature unique to this particular region. The colours of red, gold/yellow and black are replicated time and time again within the book arts of Southeast Asia, and each of these colours had symbolic associations. For example, the colour of gold/yellow was always associated with notions of royalty. Something that was associated to ideas of kingship would have suited the Quran, which was, in a sense, the king of all books.

When you consider the arts of Terengganu, Kelantan and Pattani, there is a visual language that seems to be shared amongst the arts of these regions in the Malay Peninsula. The composition and configuration of furling and unfurling patterns, for example, is something that you’d observe looking at the works from this particular region.

² Islamic Art Gallery

Installation View at Asian Civilisations Museum

Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum

Installation View at Asian Civilisations Museum

Photography by Asian Civilisations Museum

FROM A GEOGRAPHICALLY TO A THEMATICALLY-DRIVEN CURATION

NZ: Moving the curatorial approach from a geographical to a thematic one, I am keenly aware of and also afraid of not doing the different cultures justice. With this new gallery, we’re trying to get at the essence of things, and to show how core elements were shared. We hope to provide visitors with a building kit that can be used when approaching and appreciating objects from varying cultures. At the same time, we have been quite sensitive to the different cultures displayed as well. The only way we can really do this is through text, so we do try to expound on the cultures displayed through the texts and labels in the gallery. We also understand that the juxtaposition of objects is incredibly important. In this gallery, we’ve been very careful when it comes to displaying an artwork that is clearly Quranic.

As compared to classifying objects by geographical origin, I actually think you see more diversity when objects from different parts of the world are placed within the same case. With many of the major museums and their Islamic galleries, the approach is chronological and geographical. The galleries would either begin from Arabia and then go into Iran or Iraq, or segment their collection up by dynasty. These displays are great, because they functions as textbooks for how the various regions developed. However, I think it creates static boundaries between the various art forms, which makes it difficult for viewers to pick out the relationships shared between places and cultures.

³ Green glazed Mihrab tile

Asian Civilisations Museum, c. 11th century

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

Asian Civilisations Museum, c. 11th century

Credit: Asian Civilisations Museum

THE IMPORTANCE OF LIGHT IN CURATION

NZ: One of the first few concerns any curator has, aside from the subject matter at hand, is the space that she or he is given to work with. Prior to this gallery being the Islamic Art Gallery, it was a gallery for jewelry and textiles from the region. The feel in the previous gallery was both dark and dramatic, and so we kept this spatial quality in mind throughout the curatorial process.

Within Sufi texts, the concept of light is incredibly important. We have a mihrab tile in the gallery, and the mihrab is a niche in the wall of a mosque that points towards the direction of Mecca. This particular mihrab tile bears the depiction of a lamp on it. This pendant-shaped lamp is usually fashioned out of glass, and is associated with lamps made in the Middle East, from areas such as Egypt right up to Iran. The fact that it’s here on a mihrab tile, with the Sūrat an-Nūr (سورة النور) cited on it, really shows how important light is as a governing concept within Islamic traditions.

On a more personal level, Nur is a also gender neutral name. Culturally, it is associated with notions of light as divine inspiration and revelation. Many people have the word “nur” in their names because these affiliations are so ingrained into cultural sensibilities.

Developing a gallery for Islamic art in this current time is also something that cannot be taken lightly. I didn’t want to present a gallery that was, in a sense, serious, which would have been signalled by design elements such as dramatic lighting. I wanted to create a friendly atmosphere, and I wanted people to feel like they could engage with the art when they came into the space. That’s why we wanted to fill the space with light. We wanted it to feel like a breezy walk — and that is not to say that the artworks or ideas one encounters in this gallery are not serious. We just wanted visitors to come into this gallery and to feel at ease, and to facilitate encounters that encourage contemplation.

Three new galleries, including the Islamic Art Gallery, are now open at the Asian Civilisations Museum.

For more information, visit the Museum’s website here.

For more information, visit the Museum’s website here.