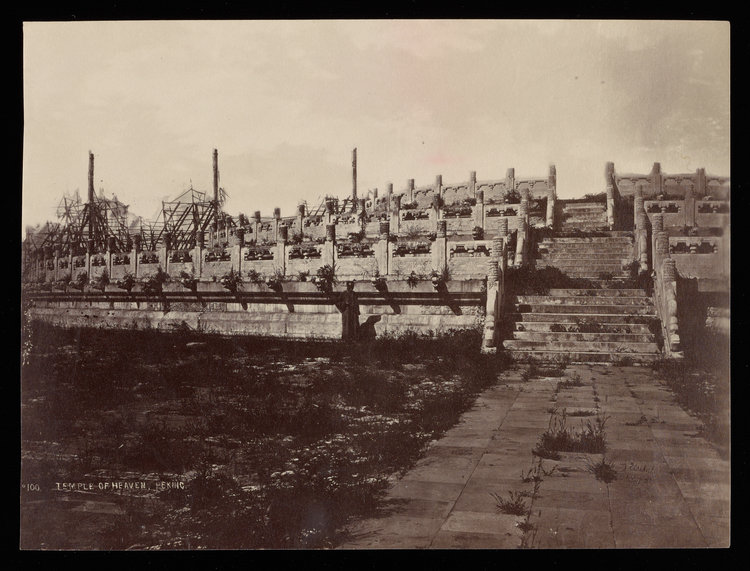

¹ Altar of Heaven, Temple of Heaven, Thomas Child

Getty Research Institute, c. 1870s

Getty Research Institute, c. 1870s

² Temple of Heaven, Peking, Thomas Child

Getty Research Institute, c. 1870s

Getty Research Institute, c. 1870s

The Temple of Heaven in Peking is a significant site that was built during the Ming Dynasty as a complex for religious buildings. In two photographs taken by the British photographer Thomas Child, pictured in the foreground are overgrown shrubbery and loose stonework. These unkempt elements stand against the intricate yet sturdy balustrades that encircle the temple itself. Whilst these photographs acknowledge the height of Chinese power and building traditions, they are also quick to visualise the kingdom's fallen and decrepit state.

![]()

Another British photographer, J.T. Thomson, is also known for his photographic documentation of China. In Thomson's photographs of Tientsin, disintegrating buildings feature prominently amongst his vignettes of idyllic landscapes and bustling street scenes.

Thomas Child and J.T. Thomson arrived in East Asia for very different reasons. Child was a gas engineer employed in Peking by the Imperial Maritime Customs Service. On the other hand, Thomson was an itinerant traveller who made his way through places such as Cyprus, Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. Despite their differences in backgrounds, both of them turned their camera towards capturing monumental yet fractured architecture.

Another British photographer, J.T. Thomson, is also known for his photographic documentation of China. In Thomson's photographs of Tientsin, disintegrating buildings feature prominently amongst his vignettes of idyllic landscapes and bustling street scenes.

Thomas Child and J.T. Thomson arrived in East Asia for very different reasons. Child was a gas engineer employed in Peking by the Imperial Maritime Customs Service. On the other hand, Thomson was an itinerant traveller who made his way through places such as Cyprus, Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. Despite their differences in backgrounds, both of them turned their camera towards capturing monumental yet fractured architecture.

³ Tientsin, Pechili Province, China, J.T. Thomson

Wellcome Collection, 1871

Wellcome Collection, 1871

⁴ Chapel of the Sisters, Tientsin, J.T. Thomson

Wellcome Collection, 1871

Wellcome Collection, 1871

The choice to highlight these ruinous elements seems curious, but it can be traced back to a longer tradition of the "picturesque" aesthetic. Back in Britain, many of the landed gentry were swept up by a new trend. To fashion ruins out of one's country home was in vogue, and drew upon a deep interest amongst British aristocracy for Classics and the Classical Antiquity. Also known as "ruin follies", walls or features that were intentionally made to look as if they were crumbling and overgrown were being built all over the country.

![]()

Sometimes, these facades even comprised of actual ancient ruins. Today, the grounds of Windsor Castle contain columns, capitals and cornices that were shipped to Britain from the city of Leptis Magna in Libya. In the name of the British crown, a military officer carted off a substantial amount of Roman architectural elements from various buildings in the city. These stones, which lay in the halls of the British Museum for many years, finally were moved to their current position at the Great Windsor Park. This particular example, which dates from 1817, exemplifies the enlightened and celebratory perspective that informed colonial missions around the world.

The exact beginnings of European photography are generally attributed to Nicéphore Niépce, with his photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras. More than a decade after the photograph was taken, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced the invention of the daguerreotype in front of the Académie des Sciences and Académie des Beaux-Arts. Photography quickly took Europe by storm. European travellers, colonial officers and surveyors quickly found a practical application for the new medium by photographing and documenting the various colonies extensively. In photographing these foreign lands, they sought to tame, understand and frame its people, architecture and geography.

Interestingly enough, new research has evidenced that the history of photography in China had begun long before the Europeans brought the daguerreotype to the Middle Kingdom. The earliest photograph of China has been dated to around the mid-1850s to 1869, and was taken by a scholar named Zou Boqi. However, Zou lived a quiet life and largely kept to himself. As such, although groundbreaking in its contents, his notebooks and findings were not publicised and spread widely.

Sometimes, these facades even comprised of actual ancient ruins. Today, the grounds of Windsor Castle contain columns, capitals and cornices that were shipped to Britain from the city of Leptis Magna in Libya. In the name of the British crown, a military officer carted off a substantial amount of Roman architectural elements from various buildings in the city. These stones, which lay in the halls of the British Museum for many years, finally were moved to their current position at the Great Windsor Park. This particular example, which dates from 1817, exemplifies the enlightened and celebratory perspective that informed colonial missions around the world.

The exact beginnings of European photography are generally attributed to Nicéphore Niépce, with his photograph, View from the Window at Le Gras. More than a decade after the photograph was taken, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre announced the invention of the daguerreotype in front of the Académie des Sciences and Académie des Beaux-Arts. Photography quickly took Europe by storm. European travellers, colonial officers and surveyors quickly found a practical application for the new medium by photographing and documenting the various colonies extensively. In photographing these foreign lands, they sought to tame, understand and frame its people, architecture and geography.

Interestingly enough, new research has evidenced that the history of photography in China had begun long before the Europeans brought the daguerreotype to the Middle Kingdom. The earliest photograph of China has been dated to around the mid-1850s to 1869, and was taken by a scholar named Zou Boqi. However, Zou lived a quiet life and largely kept to himself. As such, although groundbreaking in its contents, his notebooks and findings were not publicised and spread widely.

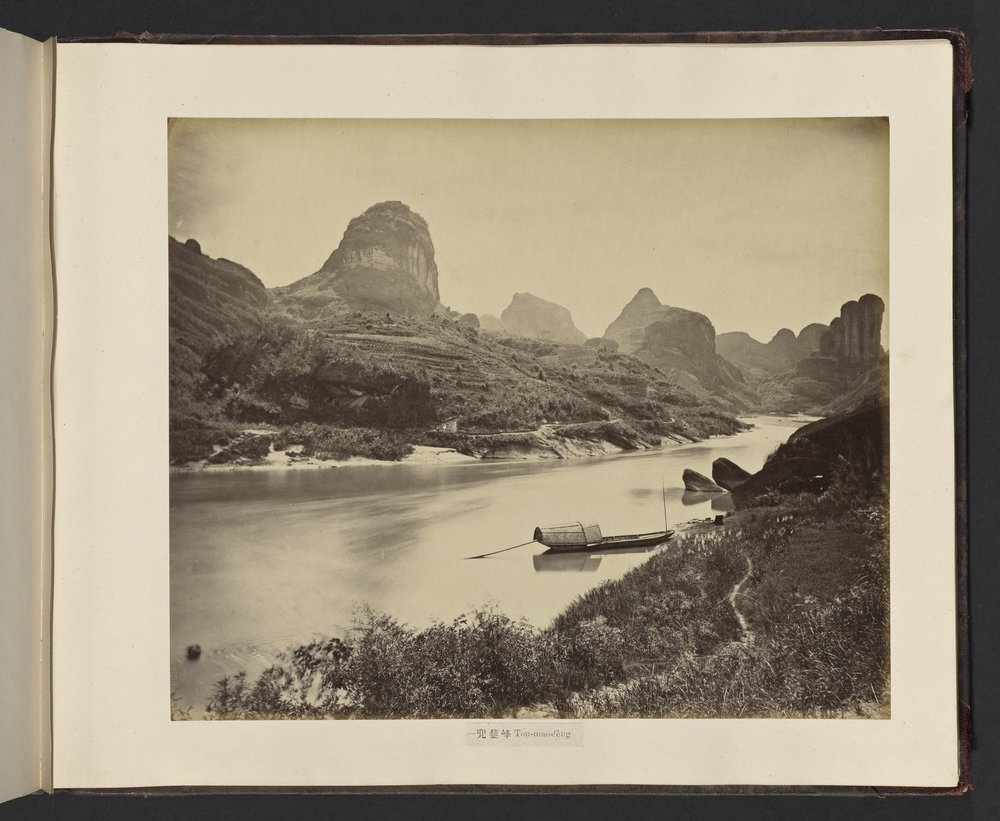

⁵ Tou-mao-fêng, Tung Hing

Getty Research Institute, c. 1862 — 1870

Getty Research Institute, c. 1862 — 1870

Although photography in China was popularised by European practitioners, Chinese artists soon picked up the skill. Many of the early Chinese photographers were painters by trade, and they set up photography studios that, with advertisements and calling cards printed in both English and Chinese, aimed to serve both the Europeans and the Chinese.

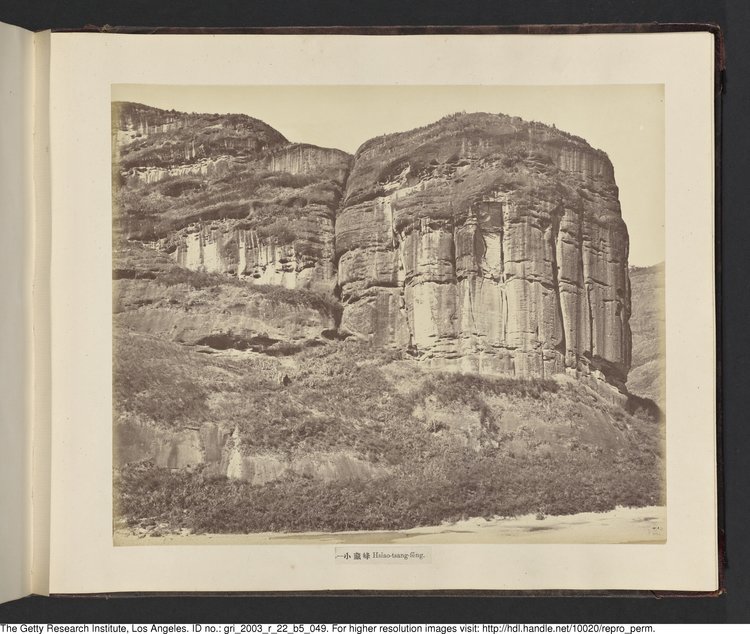

Whilst European photographers drew on their fascination with the picturesque and pastoral quality of the Chinese landscape, Chinese photographers, such as the photography studio Tung Hing (同兴), captured the dynamism of the environment in the established tradition of Chinese ink paintings (山水画). Photographs taken by the Tung Hing photography studio would have struck erudite Chinese scholars as indexical references to a vocabulary particular to Chinese art history.

Furthermore, as compared to the English or French picture captions that accompany Child's or Thomson's photographs, Tung Hing's photographs were accompanied by captions that were written in both Chinese and English.

Undoubtedly, Chinese photographers produced photographs that would have suited the tastes and preferences of their clientele. In fact, Tung Hing published an advertisement stating that the studio had views of "Foochow Tea Districts, Bridges, Chinese Temples, Monasteries, Hill and River Scenery" for sale. These photographs, although drawing upon Chinese art historical traditions, would have simultaneously fed into a European taste for the Orient and its winding rivers, rolling mountains and scenic coastlines.

Yet by incorporating a distinctively Chinese flair to their works, it is clear that the photographers at Tung Hing not only practiced but mastered the camera as an artistic craft and medium, a clear manifestation to the Self-Strengthening Movement (自强运动) that was promoted by notable members of Chinese government and aristocracy. The Self-Strengthening Movement encouraged the Chinese learning of skills and techniques from European businessmen, artists and civil servants. In doing so, the Movement believed that the Chinese could hone and better these concepts and, eventually, beat the Europeans at their own game.

These photographs are a snapshot into the European fascination for disintegrating buildings, the untouched landscape and a moment frozen in time. At the same time ruin follies were built in Britain to lay claim and historicise a claim to the mantle of a great empire, the colonies functioned as abundant sources of ruinous structures. Ultimately, what these battered landscapes offered, in the eyes of European imperialists, were unfinished portraits upon which the civilising mission of imperial ambition could be exercised and imposed.

Photographs of architectural ruins form but one of many ways in which nineteenth-century China was romanticised, exoticised and Othered by European imperialists. Chinese models were also hired and photographed in studio settings whilst wearing traditional garb and headgear. Owing to their portable size, these portraits were widely disseminated with captions such as "A Mandarin and his Wife". These photographs, undoubtedly, formed stereotypical impressions of how the Chinese people looked, dressed and lived.

With this essay, we set out to explore why the "picturesque" aesthetic dominated a large proportion of European-made photographs of China on the cusp of the twentieth century. Considering how photography developed and the importance of framing devices and exclusions in photographs, a clear picture emerges of how photographs of early modern China came to define the country in the minds of European travellers and officers. In the wake of the Second Opium War, and the growing number of treaty ports along the coast of Southern China, these photographs were a mere extension of an imaginary image of the Far East — one of decline, age and exotic intrigue.

Whilst European photographers drew on their fascination with the picturesque and pastoral quality of the Chinese landscape, Chinese photographers, such as the photography studio Tung Hing (同兴), captured the dynamism of the environment in the established tradition of Chinese ink paintings (山水画). Photographs taken by the Tung Hing photography studio would have struck erudite Chinese scholars as indexical references to a vocabulary particular to Chinese art history.

Furthermore, as compared to the English or French picture captions that accompany Child's or Thomson's photographs, Tung Hing's photographs were accompanied by captions that were written in both Chinese and English.

Undoubtedly, Chinese photographers produced photographs that would have suited the tastes and preferences of their clientele. In fact, Tung Hing published an advertisement stating that the studio had views of "Foochow Tea Districts, Bridges, Chinese Temples, Monasteries, Hill and River Scenery" for sale. These photographs, although drawing upon Chinese art historical traditions, would have simultaneously fed into a European taste for the Orient and its winding rivers, rolling mountains and scenic coastlines.

Yet by incorporating a distinctively Chinese flair to their works, it is clear that the photographers at Tung Hing not only practiced but mastered the camera as an artistic craft and medium, a clear manifestation to the Self-Strengthening Movement (自强运动) that was promoted by notable members of Chinese government and aristocracy. The Self-Strengthening Movement encouraged the Chinese learning of skills and techniques from European businessmen, artists and civil servants. In doing so, the Movement believed that the Chinese could hone and better these concepts and, eventually, beat the Europeans at their own game.

These photographs are a snapshot into the European fascination for disintegrating buildings, the untouched landscape and a moment frozen in time. At the same time ruin follies were built in Britain to lay claim and historicise a claim to the mantle of a great empire, the colonies functioned as abundant sources of ruinous structures. Ultimately, what these battered landscapes offered, in the eyes of European imperialists, were unfinished portraits upon which the civilising mission of imperial ambition could be exercised and imposed.

Photographs of architectural ruins form but one of many ways in which nineteenth-century China was romanticised, exoticised and Othered by European imperialists. Chinese models were also hired and photographed in studio settings whilst wearing traditional garb and headgear. Owing to their portable size, these portraits were widely disseminated with captions such as "A Mandarin and his Wife". These photographs, undoubtedly, formed stereotypical impressions of how the Chinese people looked, dressed and lived.

With this essay, we set out to explore why the "picturesque" aesthetic dominated a large proportion of European-made photographs of China on the cusp of the twentieth century. Considering how photography developed and the importance of framing devices and exclusions in photographs, a clear picture emerges of how photographs of early modern China came to define the country in the minds of European travellers and officers. In the wake of the Second Opium War, and the growing number of treaty ports along the coast of Southern China, these photographs were a mere extension of an imaginary image of the Far East — one of decline, age and exotic intrigue.

⁶ Yü-nü-fêng, Tung Hing

Getty Research Institute, c. 1862 — 1870

⁷ Hsiao-tsang-fêng, Tung Hing

Getty Research Institute, c. 1862 — 1870

Getty Research Institute, c. 1862 — 1870

⁷ Hsiao-tsang-fêng, Tung Hing

Getty Research Institute, c. 1862 — 1870

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FURTHER READING:

¹ Cody, Jeffrey W., and Frances Terpak, eds. Brush and Shutter: Early Photography in China. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2011.

² Cooper, Paul M.M. “How Ancient Roman Ruins Ended Up 2,000 Miles Away in a British Garden". The Atlantic, January 10, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/01/roman-ruins-windsor-castle/550199/

³ Cooper, Paul M.M. “Europe Was Once Obsessed With Fake Dilapidated Buildings". The Atlantic, April 18, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/04/fake-ruins-europe-trend/558293/

² Cooper, Paul M.M. “How Ancient Roman Ruins Ended Up 2,000 Miles Away in a British Garden". The Atlantic, January 10, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/01/roman-ruins-windsor-castle/550199/

³ Cooper, Paul M.M. “Europe Was Once Obsessed With Fake Dilapidated Buildings". The Atlantic, April 18, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/04/fake-ruins-europe-trend/558293/