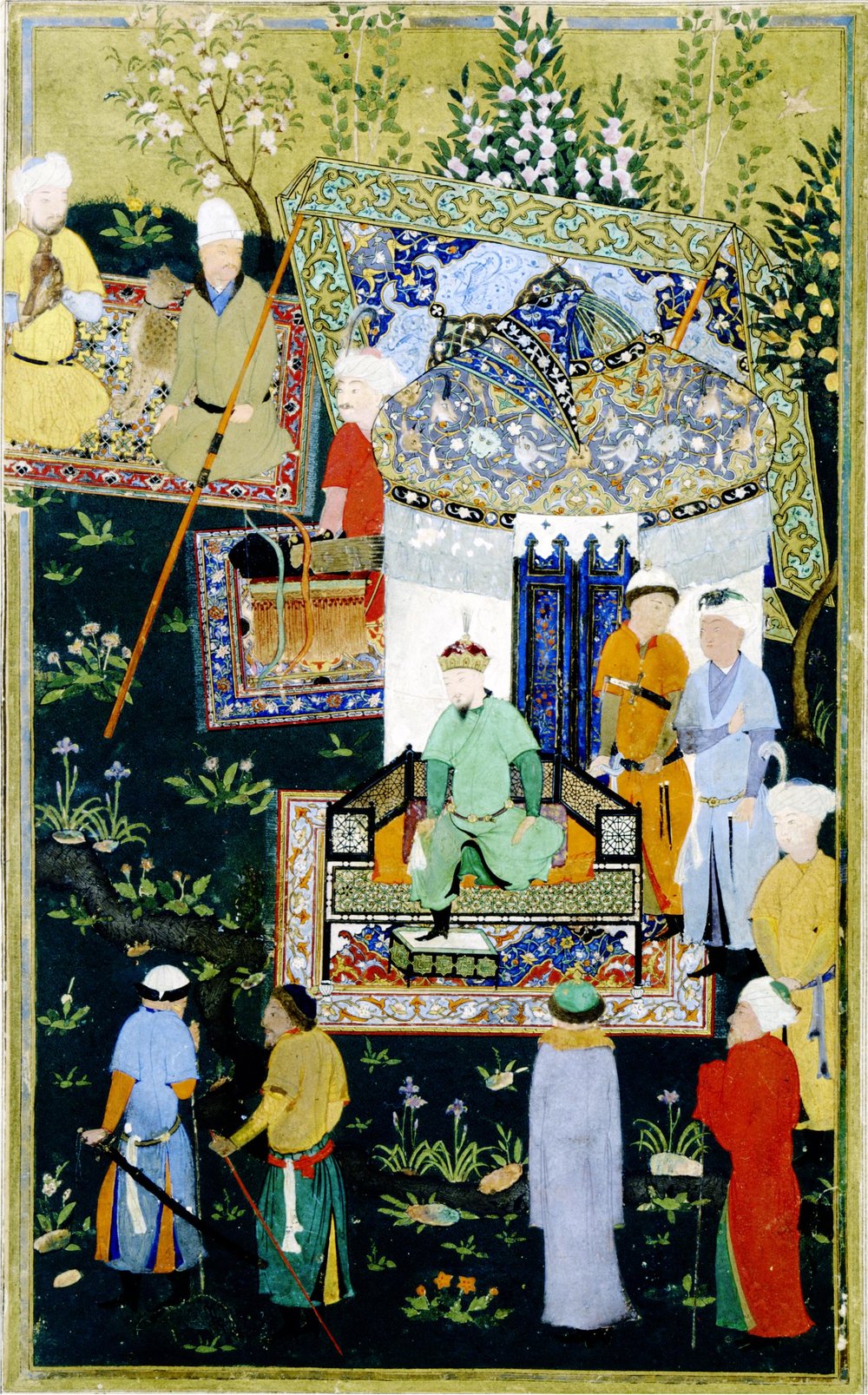

¹ Timur Granting Audience on the Occasion of His Accession, attributed to Behzad

John Hopkins University Archives, c. 1467

John Hopkins University Archives, c. 1467

The accounts of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, the ambassador of King Henry III to Timur, describe a royal encampment pitched within a garden complex. In his written narrative, tents seem ubiquitous within the Timurid imperial context. Clavijo’s observations can also be used as a worded description of the painting, Timur Granting an Audience in Balkh on the Occasion of His Accession. Here, Timur sits enthroned, and directly behind the king is a heavily embroidered tent. Timur’s tent stands in direct contrast to another tent in the top left corner of the painting, which is, instead, of a single solid colour and plain in decoration. The difference between a ruler's and a subject's tent is marked, evidencing that tents were a vehicle through which hierarchies of status could be emphasised. Through a preliminary visual analysis of this painting, it is evident that alongside architectural projects and book production, tents served as another significant tool in the articulation of Timurid kingship.

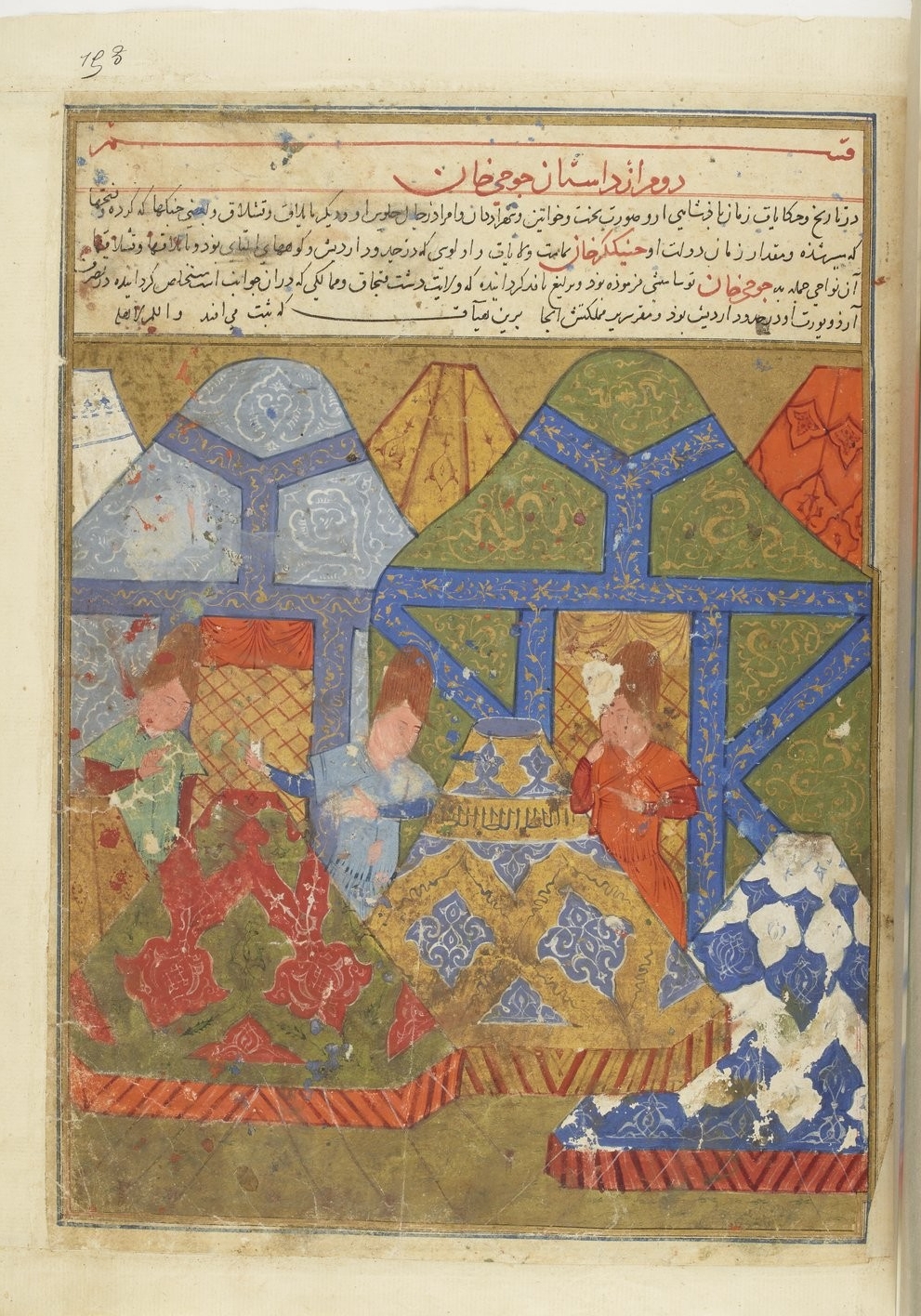

In Timur Granting an Audience in Balkh on the Occasion of His Accession, Timur is surrounded by an extravagant display of textiles. The centrepiece of this painting is the grand tent that serves as a backdrop for the imperial personage. The tent's body is pure white, and is topped by a trellis, embroidered with images of the waqwaq. The borders of the trellis seem to have precious stones inset, and the use of gold in the painting suggest that gold thread was possibly used in weaving these regal accommodations. We have already noted the comparative richness of the royal tent to another, but Clavijo's description suggests that such luxurious tents were not an anomaly.2 A folio from a Timurid Jami al-Tawarikh also gives us an evocation of what these layers of soft furnishings might have looked like. It also seems likely that no two patterns were the same. Placing distinctive fabrics beside each other created variegated visual zones, where each tent retained its individual aesthetic but was seen in relation and comparison to another. A tented enclosure could even be further subdivided through the use of doors or silken nets, further complicating access to royal figures and their private spaces.3 In remaining inaccessible but clearly visible through the tent as a market, royalty was elevated by artificial barriers of textiles.

Clavijo wrote that whilst Timur was in a "jovial mood", he ordered that the ambassadors be clothed in robes.4 This was a physically tangible moment where subjects received a cloak of favour and protection from the king. These ceremonies were carried out in the Timurid royal encampment, which was itself a labyrinth of fabrics. In navigating them, the bodily experience was one of negotiating these luscious interiors and fabrics, and to inadvertently, be clothed by them. As textiles clothed flesh, Timur's bestowment of robes added a tactile dimension to this experience. Those who traversed Timur's encampment and were given robes of honour were distinguished subjects, separate from those who were not within the immediate presence of the king. This correlates to what we know of pitching procedures within Timur's tent.

As everyone was seen in relation to the emir, Timur's large tented encampments therefore created a marked space where the presence of the king was. Being within this space was to be in the midst in the king's favour, thus reinforcing the authority of the emir.

During his tour of Saray Mulk Khanum's tent enclosure, Clavijo noted a set of doors depicting St Paul and St Peter respectively on each panel.6 These doors were taken from the treasury of Ottoman sultan Bayezid I, and their reuse in this context evidences the practice of "displaying trophies as symbolic affirmation of conquest".7 Ambassadorial tours were guided, and most probably narrated, by their Timurid hosts. As visitors were chaperoned around the enclosure, Timur's victory over another king was brought to life repeatedly through the display of a defeated realm's finest wares. As these items were repurposed throughout the encampment, remaining within imperial tented spaces became analogous to being within the presence of a powerful militarial force.

As Timur moved his royal retinue seasonally, the mobility of these tents and their treasures ensured that they weren't only showcased in one place.8 The itinerant lifestyle of Timur ensured maximum impact in enforcing this narrative of the king as triumphant conqueror. This image was strengthened by the fact that Timur's successes with militarial warfare. The reality of the situation, a warlord triumphant over major political opponents on the scene, was played out on the stage of the tent through the forceful removing of luxury items from his defeated foes and their reinvention in a Timurid imperial setting.

In Timur Granting an Audience in Balkh on the Occasion of His Accession, Timur is surrounded by an extravagant display of textiles. The centrepiece of this painting is the grand tent that serves as a backdrop for the imperial personage. The tent's body is pure white, and is topped by a trellis, embroidered with images of the waqwaq. The borders of the trellis seem to have precious stones inset, and the use of gold in the painting suggest that gold thread was possibly used in weaving these regal accommodations. We have already noted the comparative richness of the royal tent to another, but Clavijo's description suggests that such luxurious tents were not an anomaly.2 A folio from a Timurid Jami al-Tawarikh also gives us an evocation of what these layers of soft furnishings might have looked like. It also seems likely that no two patterns were the same. Placing distinctive fabrics beside each other created variegated visual zones, where each tent retained its individual aesthetic but was seen in relation and comparison to another. A tented enclosure could even be further subdivided through the use of doors or silken nets, further complicating access to royal figures and their private spaces.3 In remaining inaccessible but clearly visible through the tent as a market, royalty was elevated by artificial barriers of textiles.

Clavijo wrote that whilst Timur was in a "jovial mood", he ordered that the ambassadors be clothed in robes.4 This was a physically tangible moment where subjects received a cloak of favour and protection from the king. These ceremonies were carried out in the Timurid royal encampment, which was itself a labyrinth of fabrics. In navigating them, the bodily experience was one of negotiating these luscious interiors and fabrics, and to inadvertently, be clothed by them. As textiles clothed flesh, Timur's bestowment of robes added a tactile dimension to this experience. Those who traversed Timur's encampment and were given robes of honour were distinguished subjects, separate from those who were not within the immediate presence of the king. This correlates to what we know of pitching procedures within Timur's tent.

"When the tents of the lord were pitched, each man knew where his own tent should be pitched, and everyone, high and low, knew his place."⁵

As everyone was seen in relation to the emir, Timur's large tented encampments therefore created a marked space where the presence of the king was. Being within this space was to be in the midst in the king's favour, thus reinforcing the authority of the emir.

During his tour of Saray Mulk Khanum's tent enclosure, Clavijo noted a set of doors depicting St Paul and St Peter respectively on each panel.6 These doors were taken from the treasury of Ottoman sultan Bayezid I, and their reuse in this context evidences the practice of "displaying trophies as symbolic affirmation of conquest".7 Ambassadorial tours were guided, and most probably narrated, by their Timurid hosts. As visitors were chaperoned around the enclosure, Timur's victory over another king was brought to life repeatedly through the display of a defeated realm's finest wares. As these items were repurposed throughout the encampment, remaining within imperial tented spaces became analogous to being within the presence of a powerful militarial force.

As Timur moved his royal retinue seasonally, the mobility of these tents and their treasures ensured that they weren't only showcased in one place.8 The itinerant lifestyle of Timur ensured maximum impact in enforcing this narrative of the king as triumphant conqueror. This image was strengthened by the fact that Timur's successes with militarial warfare. The reality of the situation, a warlord triumphant over major political opponents on the scene, was played out on the stage of the tent through the forceful removing of luxury items from his defeated foes and their reinvention in a Timurid imperial setting.

² Folio from Jami al-Tawarikh

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, c. 1430-1434

³ A Party At The Court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara, left leaf of the Bustan of Sa'di frontispiece

National Egyptian Library, 1488

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, c. 1430-1434

³ A Party At The Court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara, left leaf of the Bustan of Sa'di frontispiece

National Egyptian Library, 1488

Scholars also note that "Timur and his court lived in tents during most of the spring and summer, and moved into palaces and residences only with the arrival of inclement weather".9 Although the Timurids had the ability and expertise to execute grand building projects such as the Bibi Khanum Mosque and Kök Saray, Timur's choice of residence was the tented encampment. Clavijo observed the interior of a tent as being decorated with numerous "silver-gilt falcons".10 Within Saray Mulk Khanum's tent enclosure, elaborate furnishings were also abundant.11 Clavijo almost struggles to account for all the splendid ornaments within these impressive tents, and we must expect that there was more of such richness that he unintentionally left out.

In Timur's hands, tents became a public showcase of luxury items. In the painting, A Party At The Court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara, slender blue and white porcelain ewers and finely wrought gold platters are depicted against a tent. The tent itself comprises a body of red and pink vertical stripes, topped by a deep blue trellis dome of golden teardrops and scrolling vines. Concentrating gleaming surfaces and beautiful wares around the royal figure directed all focus towards them and was a direct display of wealth. This forwarded a narrative of urban glitz and glamour. In reappropriating the nomadic tent, the Timurids utilised a visual vocabulary of opulence recognisable within settled communities, whilst referencing a tradition rooted in a Central Asian nomadic heritage.12

A substantial portion of an arzadasht from the ketabkhana of Baysunghur accounted for the progress in tent making.13 The head librarian, Ja'far Tabrizi, reported on a tent’s assembling progress, and the calligraphic medallions that were being sewn onto its exterior.14 That imperial Timurid tents were part of the royal library-atelier's artistic production is key to our discussion. The ketabkhana was a meaningful cultural institution, with roots in Ilkhanid Mongol rule. Being intrinsically linked to royal patronage, it was a place where knowledge and the arts were produced and disseminated. Under the Ilkhanids, the arts of the book were patronised extensively. This allowed the book arts to flourish, linking arts production causally to the imperial court.15

On top of relocating artists, thinkers and men of faith to the capital, the sheer devastation that Timur's conquests wrought onto certain regions was reason enough for people to gravitate towards the capital, Samarqand.16 Gathering artists and visual vocabularies from every corner of the empire meant that the ketabkhana was well poised for the creation of a "seductive dynastic image" that spoke to "the cultures of Turco-Mongol Central Asia and China" and the "Islamic Iranian cultural tradition".17 Intermingling different practices together within the ketabkhana "symbolised [a Timurid] transformation from a military caste into monarchs in the Iranian Islamic mould who recognised the necessity of cultural prowess as an ideal of rule".18 The consequent visual vocabulary of refinement and fusion applied to tent making, amongst other objects, presented a ruling class who had a firm grasp on the aesthetic vernacular of the past and present.

Clavijo’s account also mentions the many gardens within which his ambassadorial retinue camped in, as Timurid royal encampments were often pitched within palatial gardens. Situating tents, an icon of the itinerant lifestyle the Mongols embodied, into the measured and domesticated space of a garden signalled a negotiation between different ways of life. The painting of A Party At The Court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara shows a walled garden comfortable and controlled environment for courtly feasting and celebration. Yet a tent is included in the image, its soft luxuriousness juxtaposed against the pavilion's comparative angularity and solidity. What this painting evokes is that tented and architectural structures were utilised simultaneously within an imperial context. Underpinning this painting is a negotiation of conflicting ideas such as that of settled and peripatetic, and of "order" and "disarray". This highlights a sophisticated approach towards presenting the royal Timurid personage.19 In complicating the relationship between what would have otherwise been seen as polarities through drawing upon various modes of living and thinking, the Timurids articulated their rule as intellectually driven amalgamative mastery.

In Timur's hands, tents became a public showcase of luxury items. In the painting, A Party At The Court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara, slender blue and white porcelain ewers and finely wrought gold platters are depicted against a tent. The tent itself comprises a body of red and pink vertical stripes, topped by a deep blue trellis dome of golden teardrops and scrolling vines. Concentrating gleaming surfaces and beautiful wares around the royal figure directed all focus towards them and was a direct display of wealth. This forwarded a narrative of urban glitz and glamour. In reappropriating the nomadic tent, the Timurids utilised a visual vocabulary of opulence recognisable within settled communities, whilst referencing a tradition rooted in a Central Asian nomadic heritage.12

A substantial portion of an arzadasht from the ketabkhana of Baysunghur accounted for the progress in tent making.13 The head librarian, Ja'far Tabrizi, reported on a tent’s assembling progress, and the calligraphic medallions that were being sewn onto its exterior.14 That imperial Timurid tents were part of the royal library-atelier's artistic production is key to our discussion. The ketabkhana was a meaningful cultural institution, with roots in Ilkhanid Mongol rule. Being intrinsically linked to royal patronage, it was a place where knowledge and the arts were produced and disseminated. Under the Ilkhanids, the arts of the book were patronised extensively. This allowed the book arts to flourish, linking arts production causally to the imperial court.15

On top of relocating artists, thinkers and men of faith to the capital, the sheer devastation that Timur's conquests wrought onto certain regions was reason enough for people to gravitate towards the capital, Samarqand.16 Gathering artists and visual vocabularies from every corner of the empire meant that the ketabkhana was well poised for the creation of a "seductive dynastic image" that spoke to "the cultures of Turco-Mongol Central Asia and China" and the "Islamic Iranian cultural tradition".17 Intermingling different practices together within the ketabkhana "symbolised [a Timurid] transformation from a military caste into monarchs in the Iranian Islamic mould who recognised the necessity of cultural prowess as an ideal of rule".18 The consequent visual vocabulary of refinement and fusion applied to tent making, amongst other objects, presented a ruling class who had a firm grasp on the aesthetic vernacular of the past and present.

Clavijo’s account also mentions the many gardens within which his ambassadorial retinue camped in, as Timurid royal encampments were often pitched within palatial gardens. Situating tents, an icon of the itinerant lifestyle the Mongols embodied, into the measured and domesticated space of a garden signalled a negotiation between different ways of life. The painting of A Party At The Court of Sultan Husayn Bayqara shows a walled garden comfortable and controlled environment for courtly feasting and celebration. Yet a tent is included in the image, its soft luxuriousness juxtaposed against the pavilion's comparative angularity and solidity. What this painting evokes is that tented and architectural structures were utilised simultaneously within an imperial context. Underpinning this painting is a negotiation of conflicting ideas such as that of settled and peripatetic, and of "order" and "disarray". This highlights a sophisticated approach towards presenting the royal Timurid personage.19 In complicating the relationship between what would have otherwise been seen as polarities through drawing upon various modes of living and thinking, the Timurids articulated their rule as intellectually driven amalgamative mastery.

During a wedding celebration in Timur's encampment, Clavijo wrote:"As the night came on they placed many lighted lanterns before the lord; and they commenced eating and drinking again; as well as the men and the ladies, so that the feast lasted all night."²⁰

⁴ A Princely Banquet In A Garden

Cleveland Museum of Art, c. 1440

Cleveland Museum of Art, c. 1440

Manuscript paintings provide insight into how tents were used as the backdrop for these convivial moments. In A Princely Banquet In A Garden, the central figures of royalty are framed by a tented structure. The bodies of most figures in the painting are turned towards the direction of the tent and the figures beneath it, further evidencing that the celebrations have been held in their honour. Tents provide lavish settings for staging a ruler's influence, but also allowed large groups of people to be included in these fêtes, resulting in displays of grandeur that were anything but private affairs. Clavijo's accounts validate this point in mentioning that Timur invited merchants and workers from the city to set up shop in the encampment.21 With the merchants and traders pitched up there, the encampment was transformed into a bustling bazaar. The force with which people gravitated towards these celebrations at Timur's orders created a bustling hub of activity was akin to the ruler’s grander ambitions.

When Timur chose Samarqand as the capital of his empire, he rebuilt the city and turned it into one fit for an emir. An imposing vista comprising of the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the Registan at either end was constructed, with a main bazaar street connecting the two landmarks.22 To relocate the bazaar outside of the city walls, albeit temporarily, focused all activity around the imperial figure and his residence. The tents could be pitched anywhere the royal retinue travelled to and still effect the same gravitational pull about the Timurid emir. In short, these imperial tented encampments were mobile capitals. They emphasised the central position of the king amidst these portable cities and the notion of the king as the builder of cities.

Tents were evidently consciously used in the consolidation and performance Timurid kingship. It has been argued here that tents created physical spaces of political relationships and power dynamics between the Timurids and the subjects in a manner similar to their built structures. Although differently experienced, it is evident that Timurids saw tents as a crucial fulfilment of the role of architecture in the enterprise of empire. Cultures, aesthetic vocabularies and lifestyles were gathered within the Timurid empire to contribute towards an effective, powerful and all-encompassing image of rule. That Timur and his successors adopted and adapted different methods to suit their own time and place signals that expanding our scope towards examining other aspects of material culture, such as tents, might prove equally if not more productive in developing a deeper and more nuanced understanding of this empire.

When Timur chose Samarqand as the capital of his empire, he rebuilt the city and turned it into one fit for an emir. An imposing vista comprising of the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the Registan at either end was constructed, with a main bazaar street connecting the two landmarks.22 To relocate the bazaar outside of the city walls, albeit temporarily, focused all activity around the imperial figure and his residence. The tents could be pitched anywhere the royal retinue travelled to and still effect the same gravitational pull about the Timurid emir. In short, these imperial tented encampments were mobile capitals. They emphasised the central position of the king amidst these portable cities and the notion of the king as the builder of cities.

Tents were evidently consciously used in the consolidation and performance Timurid kingship. It has been argued here that tents created physical spaces of political relationships and power dynamics between the Timurids and the subjects in a manner similar to their built structures. Although differently experienced, it is evident that Timurids saw tents as a crucial fulfilment of the role of architecture in the enterprise of empire. Cultures, aesthetic vocabularies and lifestyles were gathered within the Timurid empire to contribute towards an effective, powerful and all-encompassing image of rule. That Timur and his successors adopted and adapted different methods to suit their own time and place signals that expanding our scope towards examining other aspects of material culture, such as tents, might prove equally if not more productive in developing a deeper and more nuanced understanding of this empire.

FOOTNOTES:

¹ Ruy Gonzales De Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo to the Court of Timour at Samarcand, AD 1403-6 (1859): 136.

² Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 136.

³ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 160, 161.

⁴ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 139-140.

⁵ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 140.

⁶ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 160.

⁷ Bernard O'Kane, "From Tents to Pavilions: Royal Mobility and Persian Palace Design", Ars Orientalis 23 (1993): 250.

⁸ Lisa Golombek and D Wilber, The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan (1988): 180.

⁹ Golombek and Wilber, The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan (1988): 180.

¹⁰ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 145.

¹¹ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 160-161.

¹² H.R. Roemer, The Cambridge History of Iran (Volume 6) (1986): 46.

¹³ W.M. Thackston, trans, “Arzadasht”, in A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art (1989): 326-327.

¹⁴ Thackston, trans, “Arzadasht" (1989): 327.

¹⁵ A. Soudavar, "The Han-Lin Academy and the Persian Royal Library-Atelier", in History and Historiography of Post-Mongol Central Asia and the Middle East: Studies in Honor of John E. Woods, eds. by Judith Pfeiffer and Sholeh A. Quinn (2006): 472.

¹⁶ Roemer, The Cambridge History of Iran (Volume 6) (1986): 87.

¹⁷ W.T. Lentz and G.D. Lowry, Timur And The Princely Vision: Persian Art And Culture In The Fifteenth Century (1989): 160.

¹⁸ Lentz and Lowry, Timur And The Princely Vision (1989): 162.

¹⁹ Robert Hillenbrand, "The Uses of Space in Timurid Paintings", in Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century, eds. by Lisa Golombek and Maria E. Subtelny (1992): 77.

²⁰ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 159.

²¹ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 149.

²² Iranica Online, “Samarqand I. History and Archaelogy”, Accessed 7th February 2017, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/samarqand-i.

² Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 136.

³ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 160, 161.

⁴ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 139-140.

⁵ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 140.

⁶ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 160.

⁷ Bernard O'Kane, "From Tents to Pavilions: Royal Mobility and Persian Palace Design", Ars Orientalis 23 (1993): 250.

⁸ Lisa Golombek and D Wilber, The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan (1988): 180.

⁹ Golombek and Wilber, The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan (1988): 180.

¹⁰ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 145.

¹¹ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 160-161.

¹² H.R. Roemer, The Cambridge History of Iran (Volume 6) (1986): 46.

¹³ W.M. Thackston, trans, “Arzadasht”, in A Century of Princes: Sources on Timurid History and Art (1989): 326-327.

¹⁴ Thackston, trans, “Arzadasht" (1989): 327.

¹⁵ A. Soudavar, "The Han-Lin Academy and the Persian Royal Library-Atelier", in History and Historiography of Post-Mongol Central Asia and the Middle East: Studies in Honor of John E. Woods, eds. by Judith Pfeiffer and Sholeh A. Quinn (2006): 472.

¹⁶ Roemer, The Cambridge History of Iran (Volume 6) (1986): 87.

¹⁷ W.T. Lentz and G.D. Lowry, Timur And The Princely Vision: Persian Art And Culture In The Fifteenth Century (1989): 160.

¹⁸ Lentz and Lowry, Timur And The Princely Vision (1989): 162.

¹⁹ Robert Hillenbrand, "The Uses of Space in Timurid Paintings", in Timurid Art and Culture: Iran and Central Asia in the Fifteenth Century, eds. by Lisa Golombek and Maria E. Subtelny (1992): 77.

²⁰ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 159.

²¹ Clavijo, Narrative of the Embassy (1859): 149.

²² Iranica Online, “Samarqand I. History and Archaelogy”, Accessed 7th February 2017, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/samarqand-i.