“Tarot is just a tool. The images are a form of language that one can use to access what lies within.”

— AMANDA S., TAROT READERGiven that, how do we form personal relationships with images, and what sort of processes are involved in decoding these pictograms? How have the meanings we attach to these images changed over time? Through the lens of a tarot card deck, this article will explore how we read ourselves into images, and how visual artworks can facilitate ethereal experiences.

Tarot as we recognise it today has a long and complicated history. One of the earliest surviving tarot card decks, the Visconti Tarot, is a 15th-century set of cards in the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. Owned and commissioned by the wealthy Sforza Family, these cards are an object lesson in exquisite craftsmanship. Attributed to the fresco painter Bonifacio Bembo, each card features a delicate illustration and carefully applied gold leaf. As tarot cards weren't associated with divination until around the sixteenth century, this deck was probably used for a game called tarocco or trionfi.¹

These cards were luxury objects, and each individual card is made from thick, heavy cardboard. As such, they were not handled as often as the other cards in the Sforza Family collection.² Although Bembo worked primarily with large-scale frescoes, his frescoes share technical similarities to this exquisite set of cards. In two tempera panels attributed to Bembo's hand, we see similar renditions of slender, richly clad figures against an iridescent backgrounds. Bembo's style has been described by Italian Renaissance scholar Evelyn Welch as “traditional", and this is clear through his conservative renderings of space and moderate selection of poses portraiture.³ These cards so intrigued the writer Italo Calvino that he wrote a book inspired by them, titled The Castle of Crossed Destinies.

These cards were luxury objects, and each individual card is made from thick, heavy cardboard. As such, they were not handled as often as the other cards in the Sforza Family collection.² Although Bembo worked primarily with large-scale frescoes, his frescoes share technical similarities to this exquisite set of cards. In two tempera panels attributed to Bembo's hand, we see similar renditions of slender, richly clad figures against an iridescent backgrounds. Bembo's style has been described by Italian Renaissance scholar Evelyn Welch as “traditional", and this is clear through his conservative renderings of space and moderate selection of poses portraiture.³ These cards so intrigued the writer Italo Calvino that he wrote a book inspired by them, titled The Castle of Crossed Destinies.

Female Knight (Swords) from the Visconti Tarot, Bonifacio Bembo

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1426-1447

World from the Visconti Tarot, Bonifacio Bembo

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1426-1447

Empress from the Visconti Tarot, Bonifacio Bembo

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1426-1447

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1426-1447

World from the Visconti Tarot, Bonifacio Bembo

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1426-1447

Empress from the Visconti Tarot, Bonifacio Bembo

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1426-1447

Fast forward to 1909, and the tumultuous Edwardian era in the United Kingdom is about to give way to the First World War. A newly designed tarot card deck is unveiled against this backdrop, and it would later become one of the most recognisable decks in modern history. This deck is the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, a collaborative effort between the artist Pamela Colman Smith and the scholar-mystic A.E. Waite.

Both Smith and Waite were members of the Order of the Golden Dawn, and their newly designed cards mark a clear shift from earlier decks that were conceived as playing cards. This particular set of cards were created with fortune-telling in mind, and the cards' illustrations carry this function. To accompany this deck, Waite authored a book titled The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. This book provided in-depth explanation of the symbolism and imagery used in the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, and suggested ways in which these cards could be read. A short excerpt from the book on The Empress card reads:⁴

The Art Nouveau aesthetic referenced in the deck's design positions it emphatically as a product of its time. Yet Waite's writings evidence a clear intention for these cards and their images to be mined for meaning for years to come.

Both Smith and Waite were members of the Order of the Golden Dawn, and their newly designed cards mark a clear shift from earlier decks that were conceived as playing cards. This particular set of cards were created with fortune-telling in mind, and the cards' illustrations carry this function. To accompany this deck, Waite authored a book titled The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. This book provided in-depth explanation of the symbolism and imagery used in the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, and suggested ways in which these cards could be read. A short excerpt from the book on The Empress card reads:⁴

A stately figure, seated, having rich vestments and royal aspect, as of a daughter of heaven and earth. Her diadem is of twelve stars, gathered in a cluster. The symbol of Venus is on the shield which rests near her. A field of corn is ripening in front of her, and beyond there is a fall of water. The sceptre which she bears is surmounted by the globe of this world. She is the inferior Garden of Eden, the Earthly Paradise, all that is symbolized by the visible house of man. [...] She is above all things universal fecundity and the outer sense of the Word. This is obvious, because there is no direct message which has been given to man like that which is borne by woman; but she does not herself carry its interpretation.

The Art Nouveau aesthetic referenced in the deck's design positions it emphatically as a product of its time. Yet Waite's writings evidence a clear intention for these cards and their images to be mined for meaning for years to come.

IX of Swords from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Pamela Colman Smith

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1937

XVIII The Moon from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Pamela Colman Smith

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1937

III The Empress from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Pamela Colman Smith

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1937

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1937

XVIII The Moon from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Pamela Colman Smith

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1937

III The Empress from the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot, Pamela Colman Smith

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, c. 1937

Most decks today comprise of 78 cards, and many tarot readers will say that each deck brings its own unique personality to the table. Within historical tarot card decks, certain visual tools were used to signify cards such as the Empress of Swords and the Lovers. These roles have been reinterpreted in the modern tarot card decks, yet there are certain elements within each image that still remain recognisable.

On top of this, there is a clear aesthetic that surrounds a tarot card reading session today. A querant would notice a variety of crystals, each with their own energy, present in a tarot session. Anatomical illustrations of the body, palm or head will sometimes be seen adorning textile spreads or namecards as well. “There definitely is an aesthetic surrounding tarot readings, but I've been trying to break away from that," Amanda S., a practicing tarot reader based in Singapore says, “It is important to note that there are practical aspects to this aesthetic as well. For example, the cloths I use as spreads tell me where to place my cards in a reading. They also serve a protective function for the cards as well."

Today, tarot cards and their images are used to discern answers to questions about love, career, family, and more. “When I do a reading for someone, I usually am attuned to a card's meaning on two levels," Amanda begins, “First, there's the symbolic imagery on the card itself. Secondly, each card has a historical significance attached to it." In the study of semiotics, these two facets can be seen in relation to the signifier and the signified accordingly. Although not enough research has been done into the technicalities of applying a semiotical framework to this context, adopting such a perspective could shift our understanding of tarot.

Tarot expert Rachel Pollack advocated for a systematic approach to decoding tarot's images as well. In her book, she writes that “a tarot reading is not the words describing it; it is rather a series of pictures".⁵ In order to accurately decipher the implications generated from the cards drawn, a reader must grapple with the images as a visual language first. As a result, these images are no longer mere illustrations but symbols that work in tandem with each other to create networks of communicative meanings.

An emerging science has been working towards quantifying just how such visual communication is received on a physiological level. The study of neuroaesthetics is defined as the “scientific study of the neural bases for the contemplation and creation of a work of art".⁶ The relationship between an aesthetic experience and cognitive processes has long been acknowledged, but little has been done to empirically ascertain how one influences the other. Scientific experiments have been carried out in recent years to chart how the brain reacts to encounters with various genres of art. For example, the fusiform gyrus is activated when a subject is shown portrait paintings, whilst landscape paintings activate the subject's parahippocampal gyrus.⁷

Since these initial findings were published, scholars and scientists alike have offered up hypotheses as to how and why we respond to aesthetic experiences. In response to questions surrounding why art and art making traditions have endured throughout time despite its lack of connection to the biological survival of humans, Jonathan Fineberg mused that “art exercises the ability of the brain to perceive and creatively adapt to new realities, which is a fundamental survival skill".⁸ The role of art as a “catalyst" was discussed in an article on how neuroimaging technology has allowed us to study how looking at art stimulates an idle mind.⁹ In 2018, it was also announced that the Peabody Essex Museum hired a neurologist in a bid to draw intersections between neuroscience and the museum experience.

There is growing interest in determining the physical nature of how we understand and appreciate art, and this manifests itself in fascinating ways within the context of an image-reliant divinatory practice. Pollack considered this symbiotic relationship within the context of tarot in her book, Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom:¹⁰

There is a clear emphasis on the connection one feels to the images of the cards here, and this thought is reiterated by Amanda. “There are always certain nuances that come through the images," Amanda notes. Given the new synergies between humanist theories and neurological mapping technologies, we might soon be able to pinpoint just how these nuances contribute to our understanding of images in highly specific situations such as a tarot reading session.

On top of this, there is a clear aesthetic that surrounds a tarot card reading session today. A querant would notice a variety of crystals, each with their own energy, present in a tarot session. Anatomical illustrations of the body, palm or head will sometimes be seen adorning textile spreads or namecards as well. “There definitely is an aesthetic surrounding tarot readings, but I've been trying to break away from that," Amanda S., a practicing tarot reader based in Singapore says, “It is important to note that there are practical aspects to this aesthetic as well. For example, the cloths I use as spreads tell me where to place my cards in a reading. They also serve a protective function for the cards as well."

For an activity like tarot, where there are as many ways to read tarot as there are people who practice it, falling back on these aesthetics can feel also as if one is aligned with some form of structure.

Today, tarot cards and their images are used to discern answers to questions about love, career, family, and more. “When I do a reading for someone, I usually am attuned to a card's meaning on two levels," Amanda begins, “First, there's the symbolic imagery on the card itself. Secondly, each card has a historical significance attached to it." In the study of semiotics, these two facets can be seen in relation to the signifier and the signified accordingly. Although not enough research has been done into the technicalities of applying a semiotical framework to this context, adopting such a perspective could shift our understanding of tarot.

Tarot expert Rachel Pollack advocated for a systematic approach to decoding tarot's images as well. In her book, she writes that “a tarot reading is not the words describing it; it is rather a series of pictures".⁵ In order to accurately decipher the implications generated from the cards drawn, a reader must grapple with the images as a visual language first. As a result, these images are no longer mere illustrations but symbols that work in tandem with each other to create networks of communicative meanings.

An emerging science has been working towards quantifying just how such visual communication is received on a physiological level. The study of neuroaesthetics is defined as the “scientific study of the neural bases for the contemplation and creation of a work of art".⁶ The relationship between an aesthetic experience and cognitive processes has long been acknowledged, but little has been done to empirically ascertain how one influences the other. Scientific experiments have been carried out in recent years to chart how the brain reacts to encounters with various genres of art. For example, the fusiform gyrus is activated when a subject is shown portrait paintings, whilst landscape paintings activate the subject's parahippocampal gyrus.⁷

Since these initial findings were published, scholars and scientists alike have offered up hypotheses as to how and why we respond to aesthetic experiences. In response to questions surrounding why art and art making traditions have endured throughout time despite its lack of connection to the biological survival of humans, Jonathan Fineberg mused that “art exercises the ability of the brain to perceive and creatively adapt to new realities, which is a fundamental survival skill".⁸ The role of art as a “catalyst" was discussed in an article on how neuroimaging technology has allowed us to study how looking at art stimulates an idle mind.⁹ In 2018, it was also announced that the Peabody Essex Museum hired a neurologist in a bid to draw intersections between neuroscience and the museum experience.

There is growing interest in determining the physical nature of how we understand and appreciate art, and this manifests itself in fascinating ways within the context of an image-reliant divinatory practice. Pollack considered this symbiotic relationship within the context of tarot in her book, Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom:¹⁰

You can also train the intuition by spending time with the pictures, looking at them, mixing them, telling stories with them, above all, forgetting what they are supposed to mean. Forget the symbolism as you pay attention to the colours, the shapes, the very feel and weight of the cards.

There is a clear emphasis on the connection one feels to the images of the cards here, and this thought is reiterated by Amanda. “There are always certain nuances that come through the images," Amanda notes. Given the new synergies between humanist theories and neurological mapping technologies, we might soon be able to pinpoint just how these nuances contribute to our understanding of images in highly specific situations such as a tarot reading session.

VIII Strength from the Morgan-Greer Tarot, Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan

1979

XXI World from the Morgan-Greer Tarot, Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan

1979

III Empress from the Morgan-Greer Tarot, Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan

1979

1979

XXI World from the Morgan-Greer Tarot, Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan

1979

III Empress from the Morgan-Greer Tarot, Bill Greer and Lloyd Morgan

1979

Having said all that tarot readings are a “balance between intuition and action".¹¹ Beyond the neural level, contexts and our lived experiences can also determine how we engage with an image. Given that, how do these factors play out in a real life reading? There are no hard and fast rules for individual tarot readers when it comes to structuring their sessions, so we tried to get a sense from Amanda as to how she approaches her readings.

A regular session begins with the querant picking out a deck they feel most connected to out of Amanda's selection of decks. As these decisions are made rather spontaneously, querants often have to judge a deck by its cover. “I always begin by tuning into the querant's energy. It's very intuitive," Amanda describes, “But it is an important part of the process." Much of what surrounds a tarot session is often shrouded in mystery, and sessions can differ vastly from reader to reader. “I do set some ground rules with my querants, particularly with having them keep their questions open," Amanda continues, “How I interpret the cards we draw is then based on the questions they pose."

Amanda is also quick to note that our society is very different from, for example, when the Rider-Waite-Smith deck was introduced. Societal perceptions have since shifted from then, and she takes all of these factors into consideration when she reads tarot cards. “Tarot is set in old notions of masculinity and femininity," Amanda explains, “As such, I've been reading tarot in terms of the cards' traits and not in terms of gender roles." Given all of this, the images are not a didactic source of information but a framework from which to tap on vis-a-vis a querant's needs.

A regular session begins with the querant picking out a deck they feel most connected to out of Amanda's selection of decks. As these decisions are made rather spontaneously, querants often have to judge a deck by its cover. “I always begin by tuning into the querant's energy. It's very intuitive," Amanda describes, “But it is an important part of the process." Much of what surrounds a tarot session is often shrouded in mystery, and sessions can differ vastly from reader to reader. “I do set some ground rules with my querants, particularly with having them keep their questions open," Amanda continues, “How I interpret the cards we draw is then based on the questions they pose."

Amanda is also quick to note that our society is very different from, for example, when the Rider-Waite-Smith deck was introduced. Societal perceptions have since shifted from then, and she takes all of these factors into consideration when she reads tarot cards. “Tarot is set in old notions of masculinity and femininity," Amanda explains, “As such, I've been reading tarot in terms of the cards' traits and not in terms of gender roles." Given all of this, the images are not a didactic source of information but a framework from which to tap on vis-a-vis a querant's needs.

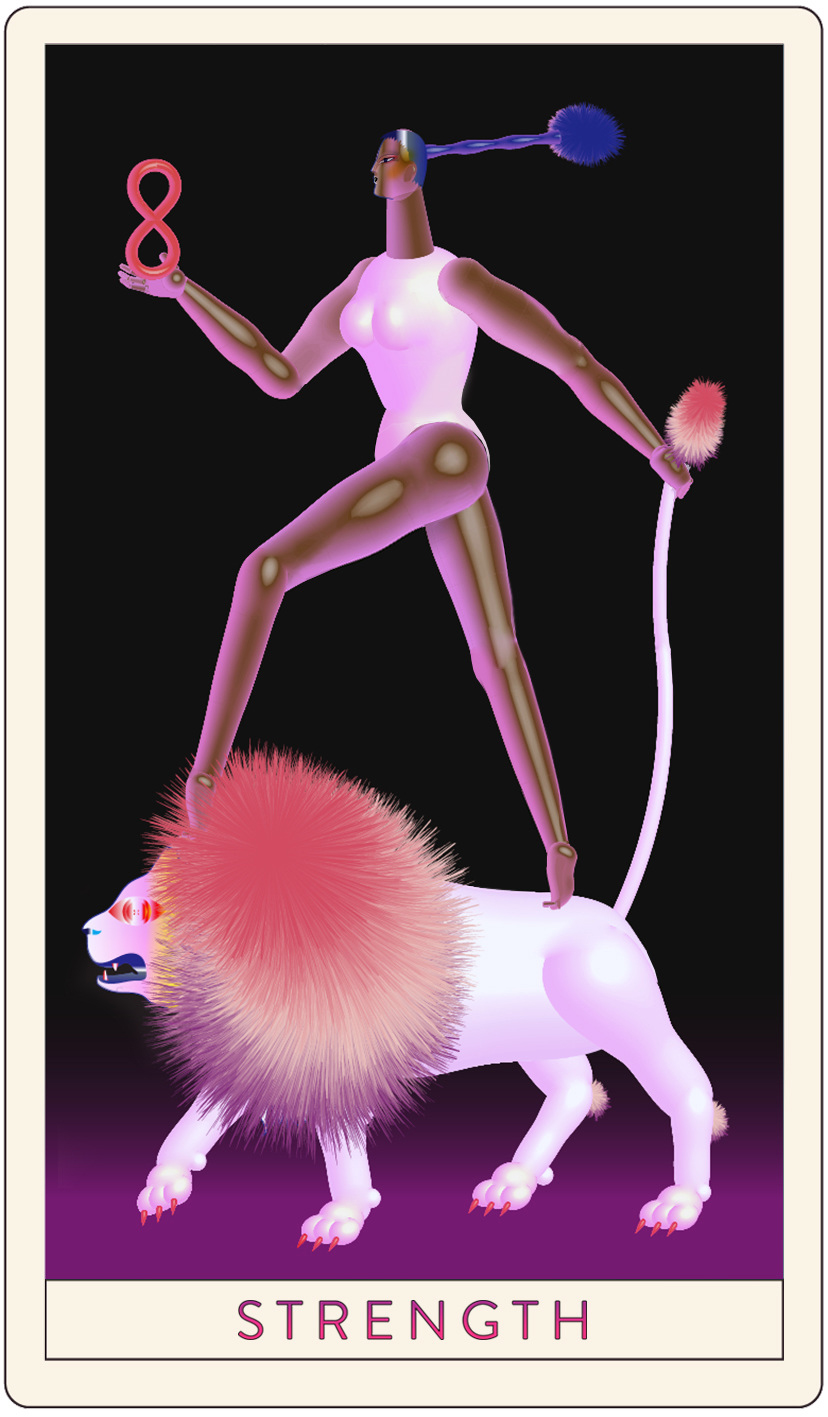

Strength from the Missy Magazine Tarot, John Ohni Lisle

2016

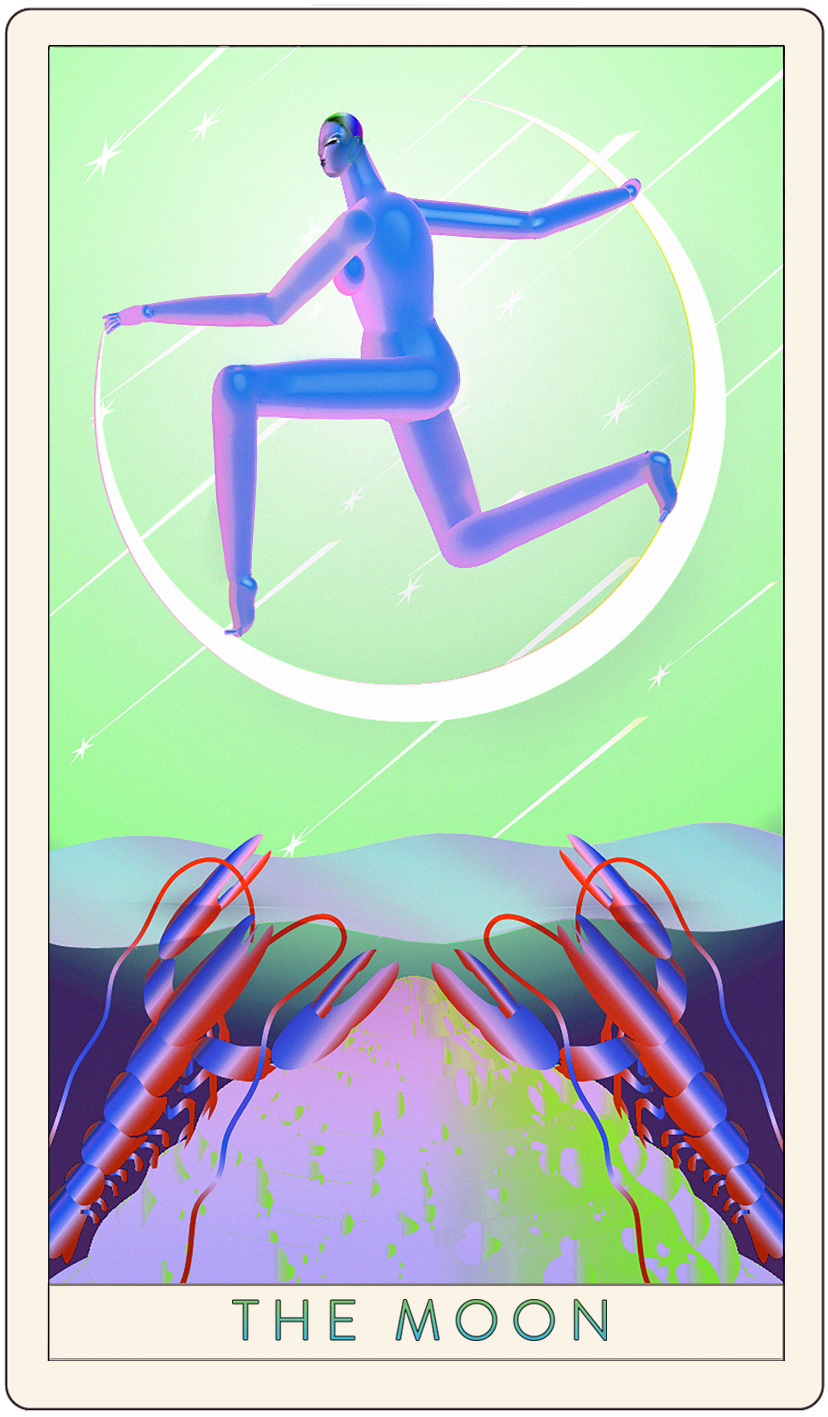

The Moon from the Missy Magazine Tarot, John Ohni Lisle

2016

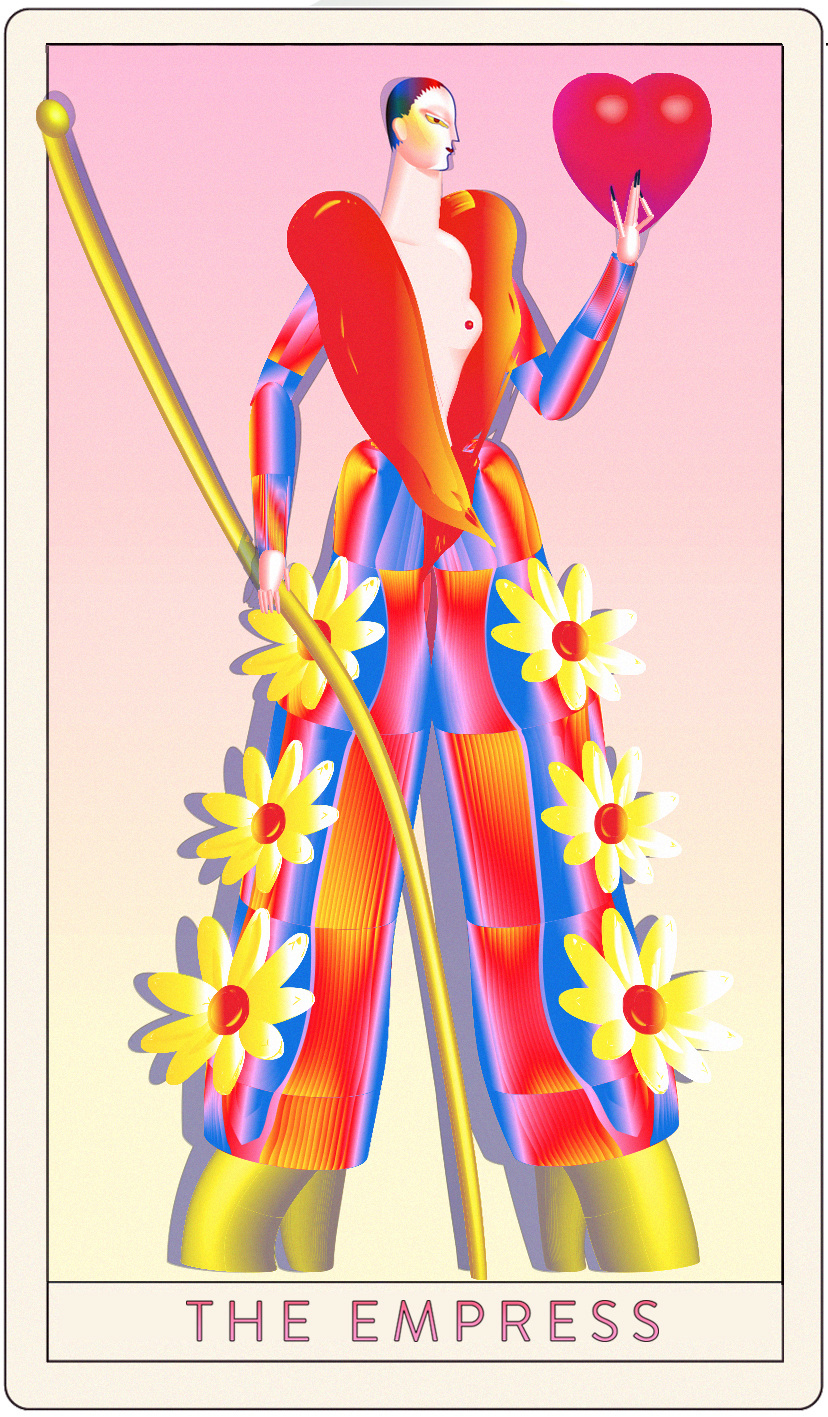

The Empress from the Missy Magazine Tarot, John Ohni Lisle

2016

2016

The Moon from the Missy Magazine Tarot, John Ohni Lisle

2016

The Empress from the Missy Magazine Tarot, John Ohni Lisle

2016

Consistent throughout the practice of tarot is a push and pull between both the lack of frameworks and the usefulness of frameworks. On one hand, approaching the images on tarot cards as a visual language provides a productive framework to understand how they operate. Yet, there is a lack of structural framework surrounding how these images can be or should be read. Folding upon this then is the fact that even when read, these tarot card images only serve as a framework upon which desires and actions are foregrounded.

It is also important to note that divining the future or cartomancy is not peculiar to tarot card reading. All around the world, we find people engaged in reading the stars, reading tea leaves and reading coffee grounds. Throughout time and cultures, humans have associated these patterns with particular meanings. Considering how deep these impulses run across time, culture and space, using neuroaesthetics and language systems as frameworks only brush the surface of how we respond to visual images.

When it comes to letting one’s soul dangle, an activity such as tarot indulges our faculties of story telling, human inquisitiveness and spiritual inclination. At the end of our conversation, Amanda summarised this form of cartomancy succinctly yet accurately. “Tarot is a rebellion against existing structures and allows querants to gain control over the unknown,” she said, “But it is also a spectacle.”

It is also important to note that divining the future or cartomancy is not peculiar to tarot card reading. All around the world, we find people engaged in reading the stars, reading tea leaves and reading coffee grounds. Throughout time and cultures, humans have associated these patterns with particular meanings. Considering how deep these impulses run across time, culture and space, using neuroaesthetics and language systems as frameworks only brush the surface of how we respond to visual images.

When it comes to letting one’s soul dangle, an activity such as tarot indulges our faculties of story telling, human inquisitiveness and spiritual inclination. At the end of our conversation, Amanda summarised this form of cartomancy succinctly yet accurately. “Tarot is a rebellion against existing structures and allows querants to gain control over the unknown,” she said, “But it is also a spectacle.”

The author would like to thank Amanda S. and Jollin Tan for their advice and input in the writing of this essay.

FOOTNOTES:

FOOTNOTES:

¹ Young, Timothy. “Mystery in a Tarot Card." Yale Alumni Magazine. Accessed 29 May, 2019. https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/4338-mystery-in-a-tarot-card.

² Moakley, Gertrude. Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family. New York: New York Public Library, 1966.

³ Welch, Evelyn. "Patrons, Artists and Audiences in Renaissance Milan" in The Court Cities of Northern Italy: Milan, Parma, Piacenza, Mantua, Ferrara, Bologna, Urbino, Pesaro, and Rimini, eds by Charles M. Rosenberg, 21-70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

⁴ Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. London: William Rider & Son Limited, 1911.

⁵ Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Weiser Books, 2009.

⁶ Nalbantian, Suzanne. “Neuroaesthetics: Neuroscientific Theory and Illustration from the Arts". Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 33:4 (2018), 357-368. DOI: 10.1179/174327908X392906.

⁷ Kawabata, H. and S. Zeki. “Neural Correlates of Beauty”. J Neurophysiol, 91:4 (2004), 1699-705. DOI: 10.1152/jn.00696.2003.

⁸ Nechvatal, Joseph. “On Neuroaesthetics, or the Productive Exercise of Looking at Art." Hyperallergic. Accessed 4 June, 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/415721/neuroaesthetics-jonathan-fineberg-interview/.

⁹ Christensen, Julia, Guido Giglioni, and Manos Tsakiris. “‘Let the soul dangle’: how mind-wandering spurs creativity." Aeon. Accessed 4 June, 2019. https://aeon.co/ideas/let-the-soul-dangle-how-mind-wandering-spurs-creativity.

¹⁰ Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Weiser Books, 2009.

¹¹ Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Weiser Books, 2009.

² Moakley, Gertrude. Tarot Cards Painted by Bonifacio Bembo for the Visconti-Sforza Family. New York: New York Public Library, 1966.

³ Welch, Evelyn. "Patrons, Artists and Audiences in Renaissance Milan" in The Court Cities of Northern Italy: Milan, Parma, Piacenza, Mantua, Ferrara, Bologna, Urbino, Pesaro, and Rimini, eds by Charles M. Rosenberg, 21-70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

⁴ Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. London: William Rider & Son Limited, 1911.

⁵ Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Weiser Books, 2009.

⁶ Nalbantian, Suzanne. “Neuroaesthetics: Neuroscientific Theory and Illustration from the Arts". Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 33:4 (2018), 357-368. DOI: 10.1179/174327908X392906.

⁷ Kawabata, H. and S. Zeki. “Neural Correlates of Beauty”. J Neurophysiol, 91:4 (2004), 1699-705. DOI: 10.1152/jn.00696.2003.

⁸ Nechvatal, Joseph. “On Neuroaesthetics, or the Productive Exercise of Looking at Art." Hyperallergic. Accessed 4 June, 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/415721/neuroaesthetics-jonathan-fineberg-interview/.

⁹ Christensen, Julia, Guido Giglioni, and Manos Tsakiris. “‘Let the soul dangle’: how mind-wandering spurs creativity." Aeon. Accessed 4 June, 2019. https://aeon.co/ideas/let-the-soul-dangle-how-mind-wandering-spurs-creativity.

¹⁰ Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Weiser Books, 2009.

¹¹ Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Book of Tarot. London: Weiser Books, 2009.