For the first few posts here at Object Lessons Space, we'll be speaking to the artists who were a part of The Deepest Blue.

We begin this series with a heartfelt chat with Renée Ting. Renée is an independent creative producer, artist and project manager. Her practice is wide-ranging, and encompasses works such as mixed media, site-specific installations and photography. Drawing on her love of literature, Renée’s works explore how words influence and weigh in on our everyday lives. She also consistently returns to complex explorations of longing, solitude, and self.

As someone who wears multiple hats at the same time, Renée finds inspiration in a variety of objects and artworks. Drawing from inspiration as varied as music to poetry, we sit down with her to find out about her practice and the upcoming Singapore Art Book Fair she's directing.

We begin this series with a heartfelt chat with Renée Ting. Renée is an independent creative producer, artist and project manager. Her practice is wide-ranging, and encompasses works such as mixed media, site-specific installations and photography. Drawing on her love of literature, Renée’s works explore how words influence and weigh in on our everyday lives. She also consistently returns to complex explorations of longing, solitude, and self.

As someone who wears multiple hats at the same time, Renée finds inspiration in a variety of objects and artworks. Drawing from inspiration as varied as music to poetry, we sit down with her to find out about her practice and the upcoming Singapore Art Book Fair she's directing.

I actually hadn't seen any of these artworks before you sent them over.

Yeah, I've been trying to go past everything that we're being fed on social media these days.

By that do you mean abstract line drawings?

Yes, and cute illustrations.

¹ Untitled, Mark Rothko

Tate, 1969

So did you first see Untitled by Mark Rothko in London?

Rothko, yes. When I was in London, I saw the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition at the Tate [Modern]. From there I started to research and to read about all of these artists around the world who are challenging the context of art and how it's presented. That's how I found out about artists such as On Kawara.

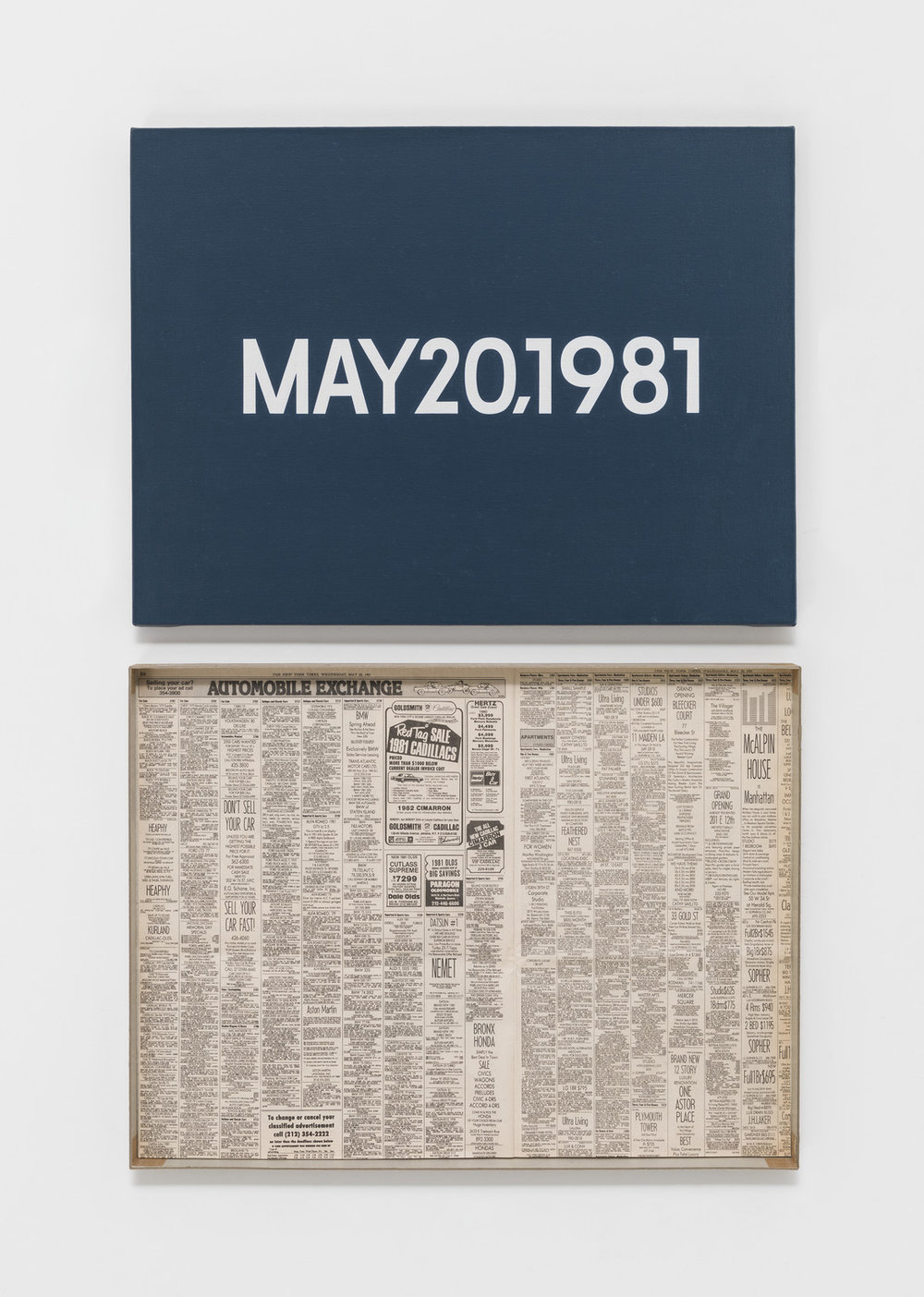

² MAY 20, 1981 (“Wednesday”), On Kawara

Private Collection, 1981

It's actually rather hard to track down On Kawara's artworks. A couple of them are owned by the Art Institute of Chicago, but a lot of them are in private collections. So this means that you can't even see photographs of them, let alone access these works.

When looking through the objects you selected for this interview, I found that you chose incredibly conceptual artworks. It seems that the concept that inform the artwork matters to you more than accessing them, or an aesthetic appreciation of them.

With On Kawara's work, it's a lot about the idea and the concept of it. Have you seen his Maps: I Went series?

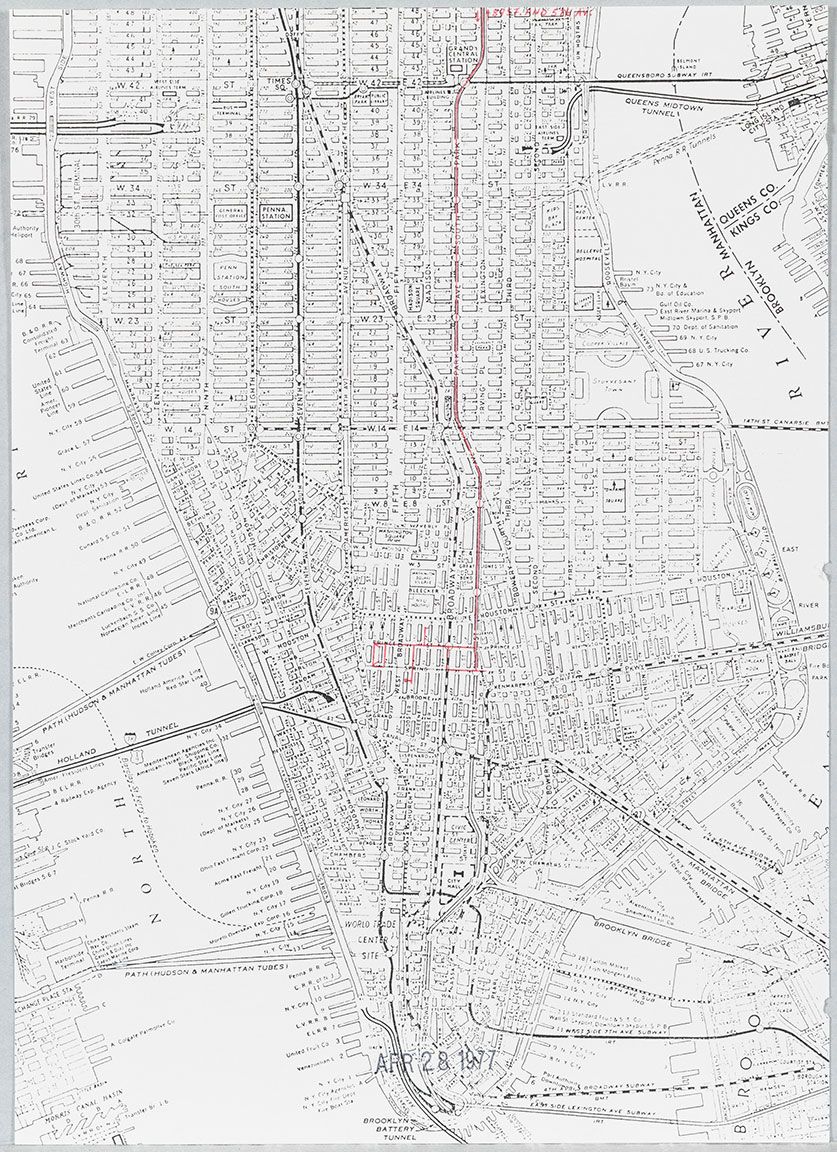

³ APR 4, 1969, On Kawara

Collection of the artist, 1969

No, I haven't.

Kawara travelled a lot and created a series of artworks where he buys a map whenever he visits a city. Using the map, he'll start walking, and he'll trace where he walks. So with every city you'll have a red line that goes through wherever he walked that day.

Another series he did was with postcards he sent to his friends. He's super elusive, almost like a hermit, but he'll send postcards to his friends with statements such as, “I'm still alive."

Out of all of these, the Date Paintings are his most famous series. One thing people don't realise is that these paintings come packaged in a box he wraps in the day's newspapers.

All the ideas and concepts that lie behind the work are so simple, yet they can be overlooked very often. One could look at something like that and not think that there's anything great about it, or that it's not difficult to make, it's something anyone could do. But it was really the idea of practising something everyday, of working at something everyday, and of doing something so fundamental, like walking, everyday, that interested me.

A longstanding criticism of a lot of conceptual, contemporary art is the statement, “Well, I could do that too". I watched a video that featured Elisabeth Sherman, the assistant curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In that video, she said that whilst a lot of modern and contemporary art can sometimes be about the skill, other works are driven by an idea as compared to skill. So whilst you could have done that painting, the key point is that you didn't.

Was it that particular aspect of the work that drew you in? Some people get affronted by minimalist art, and they think that work as simple as that should not sell for that much money or hang on gallery walls.

Not really. I discovered a lot of these works at a point of time in my life where I needed to go back to basics. It started about a year ago where everything just felt very overwhelming all the time. I was in a routine where things needed to be done every single minute. I needed to be productive every single minute, and it just felt like the world was going at a thousand miles a second for me. It got very exhausting. It got to a point where I was like, fuck everything. It felt like the more time I had, the less able I was to do all the different things I wanted to do. I felt like I needed to figure out what was important to me, because at that time I did not know. I did not know who I was, what I wanted, what I liked and what I didn't like. I tried and discovered a lot of new things during this time.

Because of that, it came down to the simplest ideas, gestures, actions, thoughts and movements.

Everything, for me, had to be pared down to the basics. Only then could I figure out what I wanted to do and what I was interested in.

In the midst of doing all of that, I discovered all of these artists who were asking questions that were similar to mine. They were doing very profound things with simple actions and gestures. That was what drew me in.

For anyone who's had a preliminary look at the personal projects you've embarked on and the sort of things you document, it becomes clear that you don't seem to be drawn to large canvases that require huge display spaces. Instead you work on documenting things such as reading projects and tiny moments that reward close looking . Do you think there's something that you consciously want to hold on to as a moment, or is there something else that drives this documentation of everyday moments?

I started doing year-long projects by taking a photograph a day. From there, it became a thing, rather naturally, to go on extended projects. I think that when it comes to a project that extends over a long period of time, it takes a lot of discipline and commitment. When I first started these projects, I did not have much time — I was constantly working. So the reading projects were a passive way for me to get something creative done.

I later decided to make extended projects a thing because it felt like, if anything, for me, it was about the commitment behind it. I went on this Antisocial Media project for six months. A year felt like too long, as if I'd lose all my friends or get very out of touch with things. For the six months, it forced me to really just be quiet. To not succumb to things that were being fed to me involuntarily. It forced me to be in the moment. It made me see a different side to our country, or at least the people around us. For example, I'd be having a conversation with someone, but once someone picks up their phone, the both of you just sit there in silence. It really forced me to be present. At that point in time, I felt that was the best thing I could do for the people around me.

⁴ Project Antisocial Media, Renée Ting

2017

2017

With projects that run on for an extended period of time, do you begin to wonder how you could conclude the project, or if you've explored the concept behind it enough? Have you felt like you've been able to conclude each project well, or do you still continue to explore the various concepts albeit in a less documentative fashion?

Specifically for Antisocial Media, it was because I needed it at the time. Things got very overwhelming, and I felt like I had to keep up with a lot of things, which caused anxiety and stress. Because of that, I felt like I needed to stop. Everybody wanted to talk and know how I was doing, and it's not that I wasn't appreciative of that — but it was too much for me, and I needed to shut it out. I decided to announce it because I wanted people to know that it was a conscious choice. When I posted about the project, someone commented that the very fact I felt a need to announce it meant that it would most likely not work out. But I wanted it to be a very active choice.

Coming out of it was very terrifying. It felt a bit like a mythical creature whose eyes I couldn't look into.

This feels so strange — we're just talking about social media here.

Yes, and six months wasn't very long either. Yet it still felt very weird. I logged in, but I couldn't bring myself to check my feeds. I wanted to be very honest about that fact that there wasn't a big insight from the six months I spent away. If someone wants to go on a similar project, one should not expect to come out of it enlightened or feeling zen. It was really to force me to be with myself and be alone, without the distraction of anything else.

Sometimes we over glorify the eureka moment, and we then come to expect it from all other areas of life, be it in terms of art or even face-to-face interactions. In the face of this, normalcy and ordinary encounters can almost be offensive.

Coming back to the objects you've chosen, such as Rothko's and Kawara's works, objectively they aren't earth shattering. Untitled is just grey paint layered onto grey paint. When I met with Chloë, she mentioned that Frankenthaler's ability to just allow form and colour to exist on the canvas was incredibly brave. When you do your various creative projects, do you find yourself tapping on the notion of allowing things to just exist without assigning a particular meaning to them often?

I believe that if you can't make the world a better place, don't make it worse. The best thing that we can do if we're not going to change things for the better, is just to not fuck things up.

I don't think everything needs to be done with an intention. I think things should be allowed to just exist. A lot of the times we get jaded because we expect outcomes and results to everything. I don't know if it's the culture of our country, or just the nature of society as a whole.

With everything that I do, even the Singapore Art Book Fair (SGABF), I'm actually okay if I don't make money from the event. From my conversations with artists and people from the creative industry, many of us agree that people just need to do things for the sake of it. If people are going to be asked, oh but how do I make money from it? My question to them is then, what does it matter? To be able to create regardless of whether or not the product is groundbreaking needs to be a more present mindset in everything we do. We should be able to do things just because we want to.

Do think that creating just because you can comes from a place of privilege? Certain groups of people are able to divorce their identity from the meanings that their work end up taking, but not others, including those of minority ethnicities in the context of Singapore.

For example, a friend of mine recently chanced upon Nguan's photographs and remarked on how amazing it was that a female photographer was getting the international recognition she deserved. When my friend later found out that the person behind these soft, pastel-toned photographs was a male photographer, her perception of the artwork changed completely. Do you think it comes from a position of privilege to be able to create for the sake of creating, and to allow an artwork to exist sans meaning?

I don't doubt that I'm privileged.

Personally, I am of the opinion that giving up is not an option. I wasn't brought up in a very privileged background. We were constantly running away from creditors. But it never felt like there was any other option. It was a very natural progression for me to go into the arts industry. My dad is an artist and my mum is a businesswoman, so my sisters and I take from both personalities. I don't feel that I lay claim to the title of being an artist. When it comes to the arts, I don't feel like it's something that I claim ownership of. I don't claim to be an artist. In fact, I stay quite clear from the word. Artists are a different breed, and they think very differently to the majority.

With regards to creating what I want because I want to, I don't think it stems from a position of privilege. I think I do it because I just don't give a fuck.

Is creating necessary for you? Either as a form of expression or a way of life?

To a certain extent, yes, but not as much as a full-fledged artists. When I talk to friends who are artists, I tell them that creating doesn't count me. Doing administrative paperwork counts me. I see myself more as an administrator in the arts, as compared to an artist who does administrative work.

What's the difference between the two?

So I'm happy to apply for grants on behalf of artists and collectives, but I have to be in the creative industry. I can't do it for, say, a shipping company.

So now that you're creating work for the exhibition, The Deepest Blue, does it feel like you're occupying quite a different space?

Yes, definitely. For me, paperwork and invoices are second nature. It's a formula. In school, I really liked math. But with the show, I had a thousand different ideas that the practical side of me sifted through. There were so many different layers I had to explore in order to create something that I didn't hate. By nature, I feel like everything I put out creatively, I end up hating. The only thing that I don't hate, and that I know I can do well, is paperwork.

The show was interesting for me. I'm currently in a space where I'm trying a lot of new things. I've recently started learning to play the volca beats. How I work the synthesiser is that it comes to me as a formula. On top of this I'm trying to paint. All of these things are outside of what I'm usually comfortable with, but yet, I'm doing these things within a space that I enjoy.

The objects you've chosen really reflect this. They're a bit of everything. You've chosen pieces of music, poetry, visual artworks and a camera. Why this multidisciplinary approach? Is it second nature to you, or something that you're conscious of?

I think it was mostly because you told me that it could be anything, so I really went ahead and chose just about everything.

I also don't think that anybody is really inspired by just one form of art object. Also, because I don't work in one fixed medium, I think that everything works as long as it speaks to me. If music brings out an emotion in me that a poem can't, then why not? I've always been very fascinated by artists that are multidisciplinary, or artists that completely master their form.

And arguably, one can't really truly be an artist in the fullest sense of the title if one does not constantly push at the boundaries.

Definitely. I've been fascinated by photography for a very long time, but for a while it limited me. It seemed like because I was good at photography, I should stick to it. For the past year, I've moved away from that by trying things like painting and music. If what I create turns out to be shit, then so be it. But at least I tried it.

For as long as I've known you, you've shot primarily in film. Ahead of this interview, you also included an Olympus Pen EE-3 in your objects sheet, which is a half frame camera. Tell us more about why you chose it. Is it also a camera that you use?

Yes. The Olympus Pen EE-3 was the very first camera that I bought when I started using film. I used to shoot on a Yashica SLR, but I bought a half frame because it was portable and easy to travel with. Another reason why I bought it was because with a half frame camera, a single roll of film now gives you 72 shots. To actually complete an entire roll of film requires a lot of commitment. Although it still uses the 35mm film, the process of getting the entire roll developed now takes much longer. It was that idea that fascinated me.

I almost hardly shoot with digital because it's too easy, and it's too perfect. I'm also a bit of sadist because I try to make things difficult for myself.

I will never try to find the easiest way out, or the easiest method with which to complete a task. I'm more interested in the purest, the most natural, or the most original technique.

Even right now, I'm not really delving into the medium completely. There are photographers who even develop their own photographs. Even if I don't do that actively, I need to know how the developing of films work.

⁶ Art/Life One Year Performance 1983-1984 (Rope Piece), Tehching Hsieh

1983-1984

Is the process behind getting the photograph important to you?

In just about anything, I think that the process is more important than the actual result.

I have always been more fascinated by the “in-between" in art, music, or even photography. There is a lot that goes behind producing and creating a piece of work that people sometimes don't realise. That is why I'm intrigued by works such as Kawara's Date Paintings.

This also reminds me of the Taiwanese performance artist, Tehching Hsieh, and his year-long performative artworks. He did a piece where he took a photograph of him punching in a timecard every single day for an entire year. In another piece, he tied himself to a woman for a year with a piece of rope. They would sleep, they would eat, they would do everything beside each other for an entire year, but they would not touch each other. There was one piece that he tried to do, but failed, because he was arrested. In the work, Hsieh avoided going underneath any shelter for a year. He could not walk under bridges, and he would sleep outdoors. Someone called the police on him, probably out of concern; but when he was arrested and put into a van, he broke. It devastated him to have to cut his work short.

For me, it's the time and it's the commitment that brings weight to your final product.

The context that backstories provide to artworks are always interesting. It sometimes seems that if one could understand who the artist was, or how the artist's personality was like, then one could make sense of his or her work.

Many of the artworks you've chosen for our conversation seem to have the ability to exist separate from their creators. Was this something you were conscious of when putting this list together?

I don't think it was something I consciously thought about. The objects and pieces I chose are items that are speaking to me right now, at this point in my life.

For example, the speech by David Foster Wallace titled This Is Water. David Foster Wallace has actively tried to separate himself from what we are being fed. He wrote books such as Infinite Jest for the sake of it. It's an incredibly long novel, and most people can't finish it. Even amongst those who have finished it, some hate it because it was banal. Yet that was his point. He didn't want anyone to draw life lessons from him or his work. He just wanted to create something that was honest and pure — something that reflected a human condition. That, for me, has more appeal than anything else. I'm interested in the presentation of human flaws and imperfections, and the freeing of each other from the expectation of being anything else other than oneself.

I wanted to talk about what you're working on now, which is the Singapore Art Book Fair. You just spoke about how Wallace didn't believe in feeding people what they wanted to be fed, but instead fed them what he thought, they needed to be fed. That sentiment almost underscores the direction you're taking the fair this year. Why was that a choice you made, and do you feel that this is a natural maturing of the fair given its history?

It fundamentally stemmed from frustration. When you look at the previous editions of the Singapore Art Book Fair, we were very driven by logistical concerns. The art book fair is a hybrid. It is an in-between and occupies middle ground because it's not an art fair like Art Stage Singapore or Affordable Art Fair. Neither is it a book fair — it isn't literary in the way Singapore Writers Festival is.

It is also an in-between because it is where artists who create books can showcase their wares. It is a place for creatives such as Atelier HOKO, who have done an entire book on the apple — how we hold it, and how we eat it. The Singapore Art Book Fair is a platform and ground for artists, publishers and book makers who don't quite fit into any particular category comfortably. Because of that it has to set itself apart from other events, such as Public Garden. Public Garden is a good platform for creators and craftspeople, but the Singapore Art Book Fair has to move in a direction that separates itself out from other festivals in order to avoid overlaps.

Also, I felt it was about time we started feeding our audiences good shit.

I want people to walk in and go, “Wow. I never knew that Singaporean artists and publishers were working on such things". I want people to pick up a book and be enriched by its content. We have to push it in a way that challenges the status quo.

But, why now? Is the general public ready for it?

Then, so be it. I don't think that should stop us. I don't think we should hold back because audiences are perceived to not be ready. If not now, then when? Are we going to wait ten years before someone else comes along to challenge the status quo again?

Crazy Rich Asians is the classic example of what Singaporeans think Singaporean writing is like. Yes, there is a huge market for that, but only because that's all we've been feeding the public. It's not the public's fault for not getting it. The onus is on the creative industry to not dumb things down for audiences in the name of accessibility. Accessibility does not equate to over simplification.

I feel that many people see a book like Crazy Rich Asians as approachable because of its status as belonging to the mainstream. Coming back to accessibility, there seems to be a trend where people only gravitate towards the mainstream, whatever that label comes with.

Do you see the Singapore Art Book Fair as offering an alternative to what mainstream could look like both to audiences at home and abroad?

Ideally, yes, the SABF is mainstream. I don't want to target artists, creatives, or people who already know about the scene. I want to grow it to a point where aunties and uncles can come, open a book by Genevieve Leong and go, “漂亮啊" (“How pretty"). Even if that's all they have to say about it, that's enough. At least they're being exposed to different kinds of art, books, and culture.

I want it to become like the IT fair — where everyone in the country is there whenever it happens. Right now, it seems like we're all in an echo chamber. It seems a bit incestuous because we're just preaching to the choir here. What we want is to let more people know about the art book scene. Even if they don't fully understand it, at least they know of the work that, for example, DECK does. We want people to know that spaces such as DECK exist to support local artists and photographers.

That's where the challenge of the SABF lies. It's a huge balancing act. From the exhibitors, to the logistics, to the audience — everything is one big balancing act. It's about finding the best middle ground for every single aspect.

You mentioned the gap now between the artist making books, and the auntie and uncle on the street. How do you see that gap being bridged with SABF, or are you effecting anything curatorially to work towards that closing up?

Eventually, we will be.

What do you think is necessary in order to bridge that gap?

With every year, I feel like I have to do something different or try something different in order to work towards figuring out what is best. If you ask me what needs to be done in order to bridge that gap, at this point, I don't know. I'm still learning. At least for this year, my key focus is to push the fair towards a [level of] maturity.

We've had enough of aesthetically pleasing things that do nothing for us. From here on out, we need to trust our audiences, instead of assuming that they can't think for themselves. We need to trust them to have the capacity towards digging a little deeper.

It seems that for this particular edition, there is a strong emphasis being placed on being different to the SABF's previous versions. Moving forward, is there something you see SABF claiming as its own, either in terms of identity of curation for future editions?

Again, I can't say. This year is a lot about trying to reset the foundation and shift the focus for the fair. I really have to take it a step at a time, and to sabotage it by having all of these big plans.

Because the fair is independent this year, we've had to strip away a lot of things. Anything that doesn't fit into the basic feature of an art book fair — which is to showcase art books — has been done away with for now. In the future, I'd love to feature all kinds of art books, including comics. For this year, we have a zine room. But adding more magazines and art catalogues to the selection would be great. We can't afford that this year in terms of space and finances, but we're working towards that slowly. Very, very slowly.

Finally, how do you understand history? Has your relationship with history, either yours personally or in the broader sense, fed into your practice and projects?

I can only speak for history in the personal sense. I feel like what I am doing and working on now is a direct result of everything that has happened to me. I make a conscious decision to take whatever that has passed into consideration moving forward. For me, it's not so much the result as it is the attitude I do it with. I take a lot of time with the things that I do, and I try to not multitask anymore. All of these tiny things I do now are a direct result of the person I was back then.

I don't really feel a personal connection to things and objects. I used to, but not anymore. For me, everything is transient. Everything passes, everything dies, everything ends. So I try not to attach too much emotional weight to anything anymore.