Rifqi Amirul (b. 1994) is a multi-disciplinary artist whose works often deal with the in-between of things: states of suspension, transition, liminality. He probes into the construction of personal boundaries and speculative states that define one’s purpose and sentimentality towards a place. He describes the personal connection one has to a physical or an imagined place, which may not necessarily be a typical home, but could relate to a sense of familiarity, a tradition or a regular activity that becomes a part of one’s identity.

For our conversation, the artist picked out a wide variety of works such as video installations, paintings and music. We sit down to chat with him over coffee about how these works have influenced his works, the twists and turns his practice has take thus far, and what lies ahead.

For our conversation, the artist picked out a wide variety of works such as video installations, paintings and music. We sit down to chat with him over coffee about how these works have influenced his works, the twists and turns his practice has take thus far, and what lies ahead.

¹ Allegoria Sacra, AES+F

2011 - 2013

2011 - 2013

AES+F’s Allegoria Sacra is a film inspired by the painting of the same name by Giovanni Bellini. The film, interpreting the painting as a depiction of purgatory, shows a transformed airport scene that is both ordinary and mystical, beautiful and disturbing. You have also tackled the subject of purgatory in your own work, Figures of Longing. How has the depiction of purgatory in Allegoria Sacra inspired your own work?

The first time I saw this work was way back in 2015 at Art Stage Singapore. I'm fascinated by the depiction of the airport in that work — it was intriguing how the transitional space could be a way to look at identities. They were also talking about a transitional space also being a non-space, whereby there is no anthropology — there is no history, background, or gathering. There is only humans walking through and pass it. People don't tend to think much places like walkways and airport lounges where people transit through.

I've always been very interested in transitional spaces. This I think comes from my experiences of crossing the border. I lived in Johor Bahru for three years, and I was commuting here and back daily. This meant doing a close to four hour commute every day between 2012 to 2016, whilst I was pursuing my diploma. Going through this transit everyday inspired me.

The way this work is shot is very slow and steady. There airport transit lounge is a space where you can observe a lot of different identities converging in one place. Yet, they don't necessarily have to interact with one another, and everyone is just there to wait for something. They have the same kind of reason to be there.

Another part of the work is also it slowly evolves to something even more imaginative and speculative. The airport lounge turns into a forest, with airplanes becoming dragons. It's a mix of many cultures within the space, with different cultural markers. There are a lot of very traditional and accessible cultural objects that you can find in the film, which is interesting. It's like how the world views different cultures. That was quite interesting for me. In a way as well, it's inspired me to work with a more speculative lens recently. The work was quite life changing.

² Figures of Longing, Rifqi Amirul

2019

³ Inter-com, Rifqi Amirul

2018

2019

³ Inter-com, Rifqi Amirul

2018

You mentioned that your work often returns to the notion of transitory spaces. You have twice worked with I_S_L_A_N_D_S, which was a gallery space that resided in the shop display windows of Peninsular Plaza. How did the liminal quality of that space influence your work in 4D: Not Another Dimension, especially as it was a site specific group exhibition?

During that time I was also working with Substation as well — they were doing a project around how their building was being sold en-bloc. Around Singapore, there are also many buildings that are “dying”. I was just observing the architecture of Peninsula Plaza. It is an old building, and it has tons of mirrors around the escalators.

The escalator is a tool for transit. It moves people from one place to another. I think that's how I entered the project — through these escalators.

Because the escalators are so tight, when you move up and down you can only see yourself going down, and the mirror reflecting down on you. The mirror is a sort of shiny metal that seems to warp space and time. It looks like you're travelling into another dimension. That's how we made it into a show — between myself, Daniel Chong, Joel Chin and Shirly Koh. We are quite different people and different artists, and I think we made quite a creative exhibition. It's crazy. I came up with one of the bigger pieces which is a flat PVC print of the escalators. It's like looking into that warped tiny space of reflection.

Peninsula Plaza also hosts a lot of spas, nail salons and massage parlours. I was also looking at the text and fonts. They use a very interesting kind of font — decorative type faces which aren't necessarily serif but are very thin, fine, and slant sideways. It has within it sort of a reference to another space. It alludes to paradise, transporting you into another space. I was playing with that kind decorative text with the PVC work.

It's interesting to me because I_S_L_A_N_D_S was itself a transitory space which has an affinity with the ideas in your work.

This space that was so dead. Nobody goes there except massage therapists going to work. It's an interesting space to work with. I like how they try to frame everything. There are nine display boxes that we had to work with. For my part of the show I was just playing with images as a response to the space.

⁴ Transiting Dimensions, Rifqi Amirul

2018, Installation view at I_S_L_A_N_D_S

Credit: Pey Chuan Tan

2018, Installation view at I_S_L_A_N_D_S

Credit: Pey Chuan Tan

For your selection of objects, you picked out defensive architecture, arrival and departure lounges and immigration checkpoints as well. You have an interest in exploring our relationship with these detached spaces. Talk to us about that exploration of power structures and the psychology of such places of waiting in your work Borders and Territories.

During my time of crossing the border daily, I was looking at a lot of authoritative structures and objects within the immigration space. I looked at the queue poles, arrow markings on the floor, and even the humps. There are so many of them to go through, and they feel quite unnecessary. The space dictates to people how to move. There is always order and control, and these objects tower over humans in a way. There are so many security measures that people go through every day.

It is interesting how we move through spaces differently as well. For example, it's very different experience moving through a mall, where you are very free; as compared to moving through an immigration checkpoint, where everything is restricted and controlled. That was my starting point — a critique of how we relate to spaces.

I made Borders and Territories at a time when I was very angry. I felt a lot of angst while looking at authority through the lens of the migrating commuter. It is very tiring for someone to go through borders and security measures being checked all the time. It is also mentally draining. That's the system, with structures that wear you down to control you. I was observing how immigration checkpoints look like as well. The Woodlands Checkpoint looks very policed. The roof is slanted and takes on a hulking or massive form. They have these sharp points and it all looks very intimidating. I'm curious about how architecture can intimidate.

In Borders and Territories, I explored defensive structures and objects, such as barbed wire and fences. Fences separate yet are permeable in some way — small things can pass through them, but not people. Fences border places. I tried to counter or defeat the defensive object. I also tried to resist their original functions. For the work Sad Fence, I made a fence out of sponge and then crumpled it. It felt funny to me. I also made a collage from pictures I took of immigration sites, MRTs and other transitory spaces that feel controlled. All these places feature a lot of straight and harsh lines, with rigid and strong structures. They contain a lot of metal and concrete. I broke them down formally, into pieces, and arranged them into one line. It made for a very noisy collage. If I were to change the form, do I change the power too? Does it make for a more violent object? These were some of the questions I wanted to pose.

⁵ Study I, Rifqi Amirul

2018

⁶ Reconstructed Power, Rifqi Amirul

2018

2018

⁶ Reconstructed Power, Rifqi Amirul

2018

While objects can embody control and violence, they can also been seen as tools of transformation. Bodily shrouds and alien space pods can be seen through such a lens of uncanny transformation. What is your interpretation of these objects?

To date, I've been looking at spaces very critically in my practice — often with a lot of frustration and anger. Beyond that, I also want to move towards looking at things in a manner that is much more existential. During my time staying in Johor Bahru, I had a close death experience. I was in my house and I burnt the kitchen down. I think I almost died. That day, I was really tired after pulling an all-nighter. I was sleeping alone in my house and wanted to make some fries. I went to the kitchen and heated up some oil. But because I was so tired, I went back to sleep. When I was asleep, the whole thing caught fire. The kitchen was on fire, and I didn't wake up. I only woke up two hours later, and remembering the fries, went into to the kitchen. By then everything in the kitchen was blackened, and the fire had been put out. Even if I had woken up earlier, I didn’t know how to handle a grease fire. That close death experience inspired me to question — how do I exist as a migrant? I starting seeing the commuter or traveller as another form, where this role can been seen as a bodily shroud.

For Muslim burials, the dead body is shrouded in a white cloth. The dead have their body as a vessel, bringing only the important things with them, which are their sins and their deeds. That's what we believe about the afterlife as our destination. A parallel can be drawn for the traveller, where we bring our luggage bag as the vessel. It holds all our important belongings for our transit to another destination. With the bag, the traveller moves with a bodily vessel through life. They eventually end up somewhere, like how the dead eventually end up in the afterlife. This notion of transit is also then similar to purgatory, because purgatory is a space where people are neither here nor there.

To me purgatory also represents in being stuck in between — you haven’t arrived yet. I look at these spaces existentially.

It seems to me that cultural connotations are important to you in the notion of transit and liminality. How do you think one's identity facilitates their movement through a space?

If you look at Changi Airport and the Woodlands border, both are places of immigration and transit, but they have very different identities and characteristics. Changi Airport has air-conditioned lounges, and the architecture is sophisticated and exudes warmth. In comparison, the Tuas and Woodlands borders look mundane, standard, and generic. Spaces for air travel and transit are usually much nicer than spaces that greet those who travel by land or sea. There is a different kind of treatment doled out for different kinds of travellers. Migrant workers in Malaysia get very different treatment as compared to international tourists coming in through the airport. We are all commuters, travellers, and people. Yet, there are these are very observable differences.

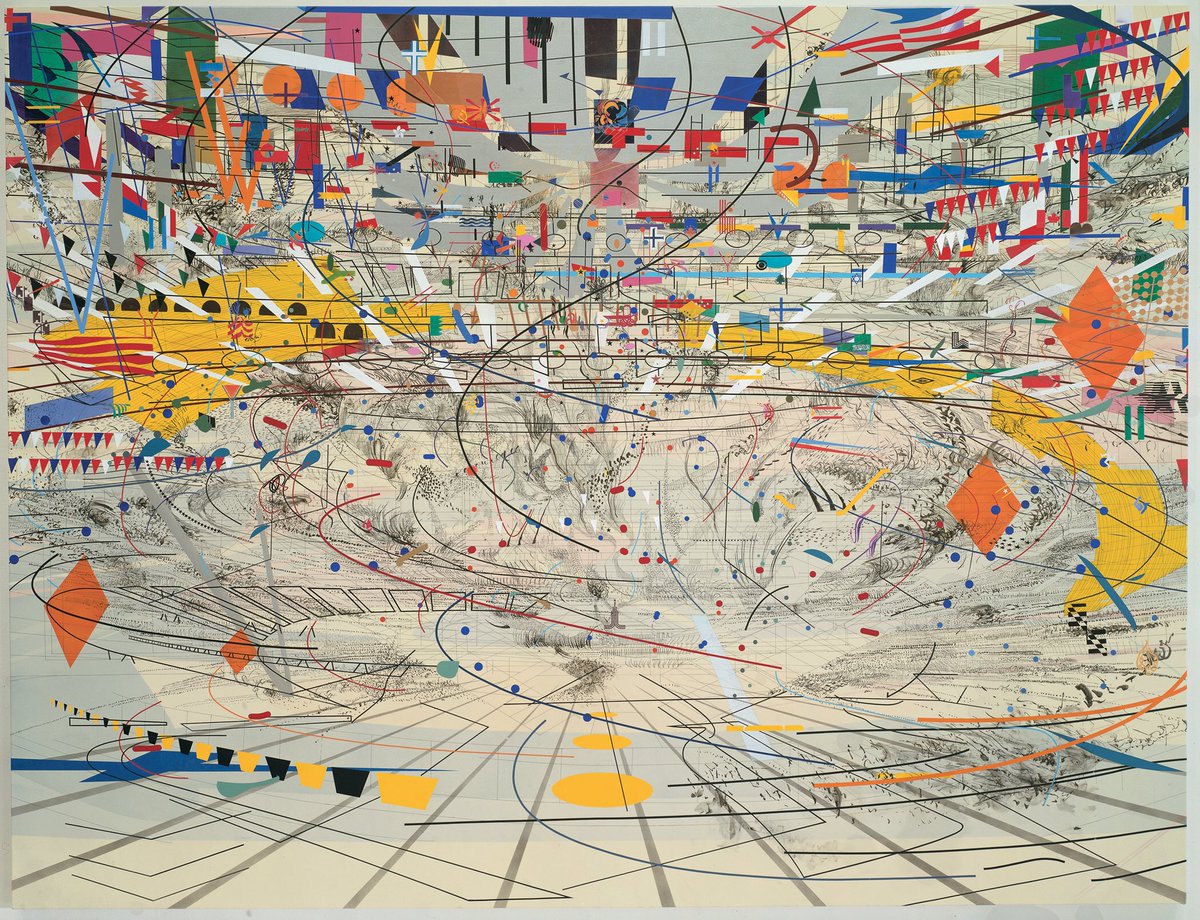

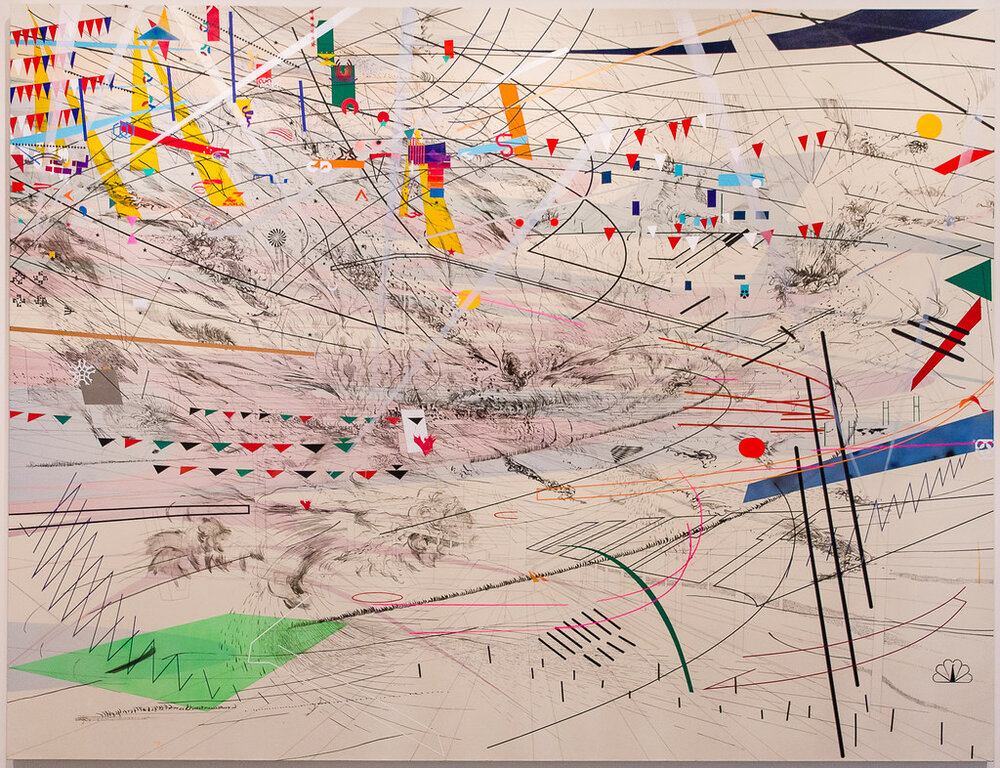

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2004

Carnegie Museum of Art, 2004

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2004

Julie Mehrutu’s Stadia triptych explores the socio-political effects and changes as they occur in built environments, such as a sports stadium. The idea of a built environment is something which you have explored frequently in your own work — what about Mehrutu’s interpretation draws you particularly to these works?

The first time I saw her works, I immediately saw this chaos and I really love that quality about them. I was really drawn to how she organises what she puts on the canvas. She almost takes on the role of a cartographer or mapmaker by superimposing a sort of psychological map on top of an architectural space. With the Stadia works, she was interested in how the Olympics brings together all of these people with different identities and cultural backgrounds and countries in celebration. At the Olympics, it is not uncommon to see the athletes or supporters from all over the world proudly representing their country on an international stage. Regardless of what is happening or unfolding, even with the backdrop of war or famine, countries will send athletes to represent them at the Olympics. Mehrutu’s painting is very chaotic, yet there's sense of a togetherness within it. However beneath it all, there is still this element of brokenness that's being left out of the conversations we’re having about these spaces.

Mehrutu also talks about managing risks in the setting of a large stadium. Everyone gathers in these places, and they can so easily become high-risk targets for violence or bombings. In these situations, a space such as a stadium suddenly becomes difficult to navigate or get through. Stadiums are not typically seen as spaces of authority or control, but that impression can be changed through these sort of events.

In gathering a group of people with vast differences in identity or culture, important changes are made to the environment.

You have picked out two pieces of music, namely Siberian Breaks by MGMT and Bach Mit Zumutungen by Vikingur Ólafsson, as part of your selection. Having also worked with sound in your pieces, tell us about how music and sound influences your work.

MGMT's song is a twelve minute song, and it describes a journey through space. It feels very psychedelic and spacey. There is a part of the song that affected me a lot. Its lyrics felt very existential and emotional to me.

Ólafsson’s piece was a reworking of a composition by Johann Sebastian Bach. It too felt very emotional, melancholic, and moving. The influence of these two pieces of music on my work is small, but I think they have made my work a lot more sentimental. The two pieces of music are also very different, but both got me reflecting on larger life questions. Why do we have to go through so much just in order to live or stay alive? How can we survive through these hardships? How we approach or look at the world in a more wholesome manner?

For a sound work that I did in school, Inter-com, I collected voices and sounds from places such as immigration checkpoints and MRT stations. I was interested in how sounds could serve as or be heard as authoritative voices. I thought about words that sounded authoritative, and the kind of sounds that would be understood or deemed as controlling. I played these sounds through a speaker that was attached to a loudhailer. The work took the form of two loudhailers talking to each other across a field. That was a fun side project.

While looking through your work, what jumped out at me is the fluidity and ease with which you traverse across different mediums as a multi-disciplinary artist. How do you see the mediums that you work in, and what is the relationship between the physicality and ideas of your work?

Medium for me isn't as important as what I talk about within my work. I always gravitate towards whatever is more accessible in that time. The medium also doesn't matter to me as much — I'm very flexible. What's more important are the imageries that I portray, like architectural borders or shrouds.

There are common images that I constantly reference across all of my works, regardless of medium, but these images are treated differently. With the shrouds, for example, I first worked with them in my prints. It later took on a more sculptural form in my graduation work, particularly in a more cage-like structural body. That was me applying or using the image of the shroud to different contexts. For the graduation work, I explored existentialism, travelling, journeys, and the sort of spaces that I relate to. I imagine purgatory as a dry land, and I used sandy and skeletal objects to convey this frustration and confusion. I also represented this vastness through the use of gradients to connote the infinite bodies of the sea, the sky and the sand.

Medium-wise, I'm always very excited to try different things.

¹⁰ Inter-com, Rifqi Amirul

2018

Credit: Lai Yu Tong

2018

Credit: Lai Yu Tong