Sim Chi Yin (b. 1978) focuses on history, memory, conflict, and migration and its consequences through photography and new media. The Nobel Peace Prize photographer for 2017, her works have been exhibited in museums, galleries, and photo and film festivals in Asia, the United States and Europe. Sim won the Chris Hondros Award in 2018, and recently joined Magnum Photos as a nominee. She is researching a book on the early Cold War that tells the story of her grandfather, his compatriots and their anti-colonial battle in British Malaya, and is working on a global project on sand.

Having just opened up two separate group shows in New York and Amsterdam, we manage to catch up with the photographer over a quick Skype session. In Singapore, a solo exhibition at LASALLE Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) Singapore, Most People Were Silent, features Sim’s photographs. These works were commissioned for the Nobel Peace Prize 2017 Exhibition.

Having just opened up two separate group shows in New York and Amsterdam, we manage to catch up with the photographer over a quick Skype session. In Singapore, a solo exhibition at LASALLE Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) Singapore, Most People Were Silent, features Sim’s photographs. These works were commissioned for the Nobel Peace Prize 2017 Exhibition.

Starting off from your selection of artworks (Y.Z. Kami’s works) and objects (Han Suyin’s And The Rain My Drink) for this interview — was that a particular rationale or reason you were drawn towards picking out such a variety of things?

I was trying to think about what kind of objects I could speak around since we wanted to focus not just on Most People Were Silent, but on the two shows I’ve just opened in New York and Amsterdam as well — which contain pieces from my British Malaya family project, One Day We’ll Understand.

I thought these objects were appropriate, and they speak to some of the things that I’ve had to work through over the past months to arrive at the pieces I’m showing now. I’m very much at an experimental and exploratory phase in my work, so I’m getting references that aren’t always photographic. Each of these have a certain bearing on the two exhibitions currently on show in New York and Amsterdam.

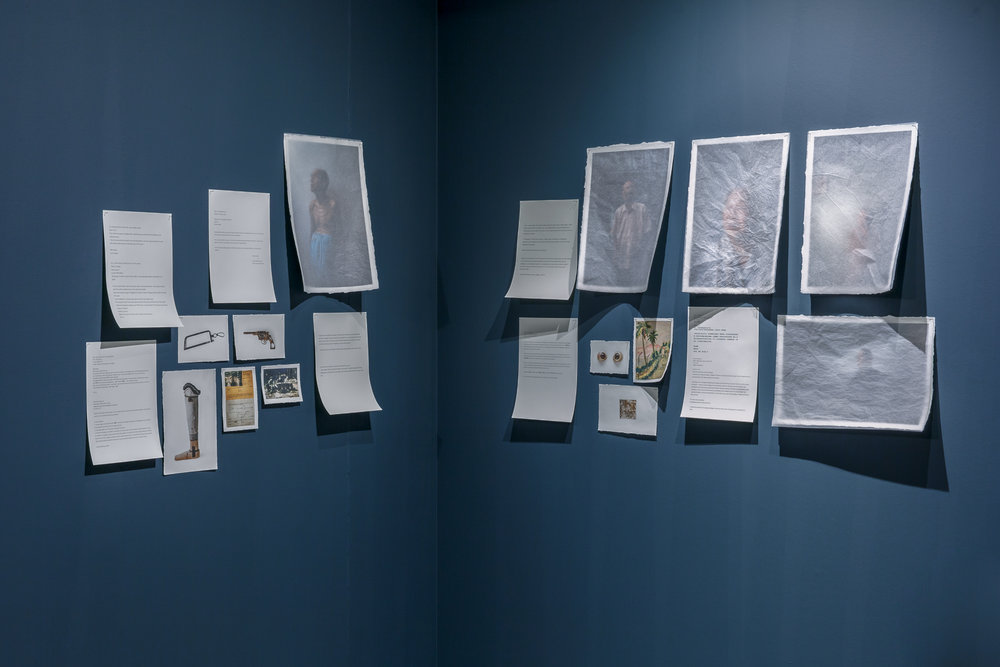

¹ One Day We’ll Understand, Sim Chi Yin

2018, Installation View at UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed

Photography by Eva Broekema

2018, Installation View at UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed

Photography by Eva Broekema

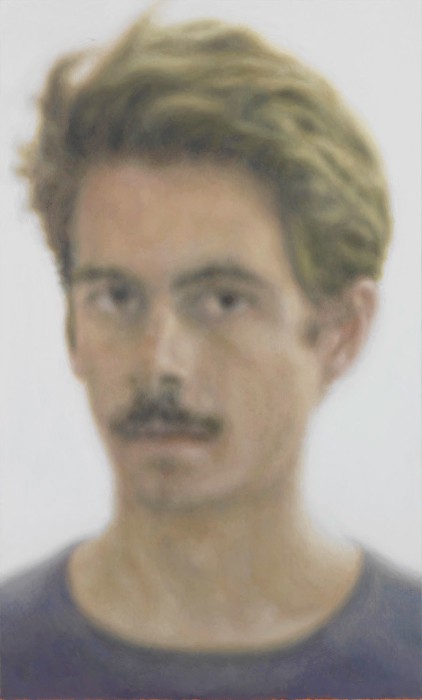

² Paul, Y.Z. Kami

Gagosian, 2014

How is the process like, and are there any differences when you showcase a body of work such as the British Malaya project in very different geographical or cultural contexts?

I’m trying to figure out what the best way of telling this complex story is, because the story means different things to different people.

I did an artist residency in Amsterdam last year, and it required me to do public presentations of my works. It wasn’t just about studio visits where people came in to see my process or fragments of my works — I had to sit on stage to present my work in front of people. I devised a performative reading of this project, and at the moment, it seems that it has been the best, quick and most accessible way of getting people into the work.

The project deals with a very complicated piece of history, and it deals with Malaya, which is a region that most people outside of Southeast Asia might be unfamiliar with. It’s been a pleasant surprise for me that audiences in Amsterdam, New York, Italy and in Singapore have received it well. There’s always someone in the audience who cries.

There’s something about the performative form, I think, and the power of the words and the visual. This, combined with the fact that I’m reading it live, really gives it a sort of power.

I’m experimenting with performative reading and with different ways of presenting photography. I kept the show in New York very simple, because I wasn’t there to install it in person. It’s a group show, and I knew it would be very crowded, so I created a very quiet piece with just six prints. The exhibition also includes pages that have been replicated from my journal. These journal-sized pages have photographs and words printed on a single piece of paper. I made the deliberate choice of non-archival paper, so that the paper ages, absorbs moisture and yellows. However, the inks with which we printed the images were archival inks. I like the feeling of this sort of paper, and the idea that it would yellow and age. It mirrors how the project is very much about the passage of time, and the fragility of memory. The piece in New York is titled Notes to Granddad, and it has six images from my exploration of our home in Meixian, Guangdong. The exhibition features notes from me to my grandfather that I wrote in pencil, similar to the text I use in the performance, when I read these in the form of a letter.

The show in Amsterdam, UnAuthorised Medium, is different because it’s not about the story of my family. Instead, it is about the story of those from my grandfather’s generation who were involved in the anti-colonial movement. For that, I chose five portraits and accompanied these portraits with photographs of objects from the war. One of the objects I chose for this interview is a photograph I took of a prosthetic leg, but the exhibition features objects, such as guns and the photographs people had of their time in prison. I printed the photographs on non-archival paper as well, and although I wasn’t there to install the exhibition, my installation instructions to the curator were pretty clear and she installed it as we discussed. What we did was that we layered the imagery.

Coming to why I chose Y.Z. Kami’s works for this interview and what that reference is about — the whole show explores the idea of the archive, and the problems of archiving.

I was working with the idea of frailty, fragility, and fallibility of human memory — the uncertainty of facts, so to speak.

What I did was to place a piece of tracing paper over the each of the five portraits displayed. The tracing paper is only tacked to the image at the top, and not pinned down. Depending on how light hits the tracing paper or how the wind or human movement flows in the room, one can get a different perception of the portrait that lies beyond the tracing paper. I’m trying to work with ideas of remembering but not remembering, seeing but not seeing. I’ve just been experimenting with different ways of spinning off pieces of this long, complex and layered project through small exhibitions of it.

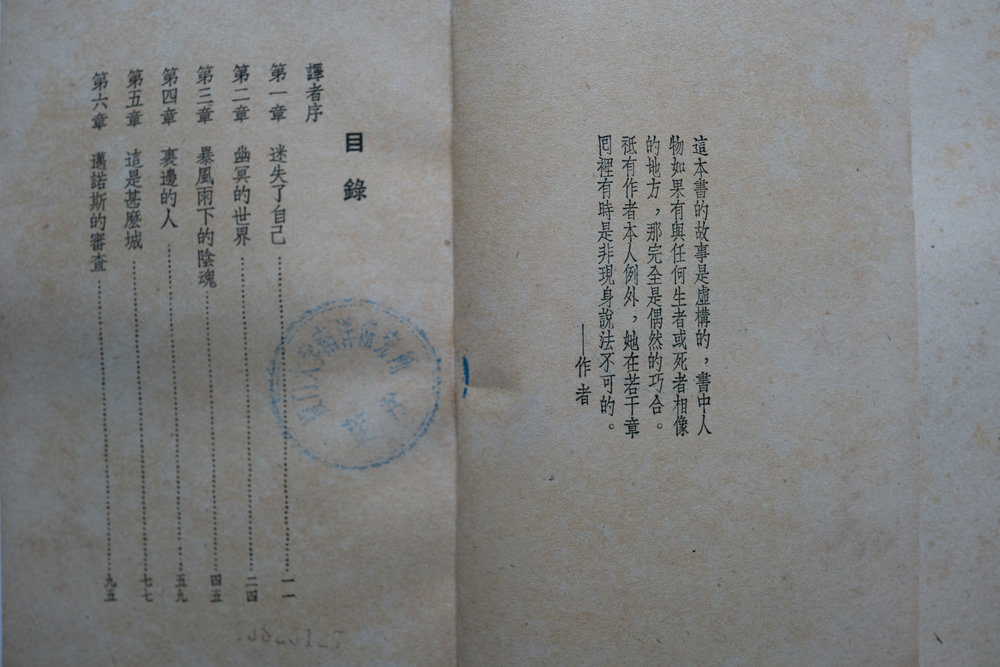

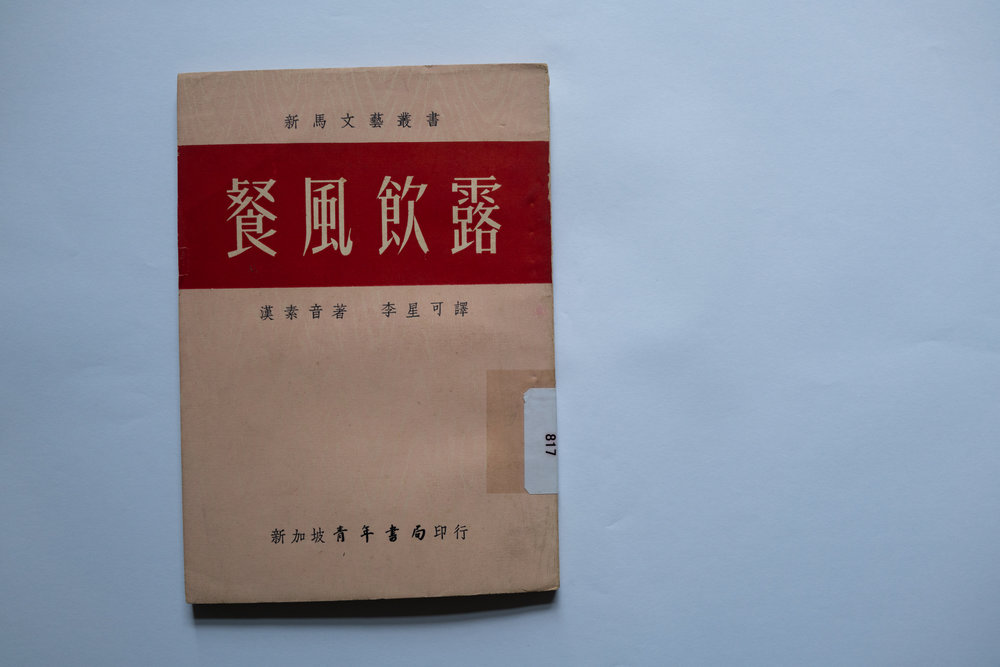

I found And The Rain I Drink by Han Suyin very interesting, and of course, I read the English version first. I took this image recently in the Xiamen University’s Southeast Asian Studies Library. The librarian kindly dug out all the books that were relevant to my research, and this was one of them. I was quite interested to see that there was such an early Chinese translation of this book. In this Chinese version, there is a page that says: “Any resemblance to real life persons is coincidental”. It clearly tells the reader that this book is a work of fiction, that it isn’t factual, and that it isn’t meant to be read as non-fiction. However the English version doesn’t feature this disclaimer. The title of the book in English, And The Rain My Drink, is referred to as a Communist song. Because of that, I’ve been trying to ask both historians and Han’s then-husband if they knew of this song, but I haven’t been able to ascertain that. When I saw the disclaimer in the Chinese version, it seemed almost like watching a movie, which calls on the reader to suspend his or her interpretation. Han lived in Malaya at the time of the Emergency, and I’ve previously interviewed her former husband. A lot of these things ring true, but these characters were probably based off composited figures. The song is something I’ve always been very curious about. She has the entire song in the book, and as it turns out, I’ve not been able to prove if it is a real song. I’ve interviewed a lot of ex-Malayan Communist Party (MCP) members, but no one knows the song. It might just be fictional.

I’m just trying to grapple with the fact that I was a student of history. I did both of my first degrees in History, and I’m about to do my PhD in History as well. I was also a journalist for about fifteen years, where it’s all about truth or the pursuit of truth and facts. I’ve come to this stage where I’m questioning a lot the role or place of facts in my art making. Han Suyin’s book is emblematic, in a way. It really speaks to a time, it’s almost a documentary, but then the reader is told that the book is a work of fiction.

³ 餐風飲露 (And The Rain My Drink, Chinese Version), Han Suyin

1956

Photograph from the artist

1956

Photograph from the artist

It’s interesting that you say that you’re reconsidering the place of truth and facts.

Was there a point in time, throughout your trajectory as a photographer, where that particular shift towards considering the slippage between fact and fiction became obvious to you?

I think it was a progression. In terms of making, I’m really only at the beginning of coming to terms with that. I’m not trying to diss everything that came before, but I think that this past year or year and a half has been a particularly important stage of my evolution. I’m not sure where it’s going yet, but I’m certainly very interested in challenging my own work and my own ways of thinking.

It was also in putting together this Amsterdam show that I’ve had to grapple with a different way of looking at fact and archiving. I’ve done about thirty oral history interviews with people who were a part of the Malayan Emergency, and when I first began, I approached the process like a historian would. I was trying to verify people’s stories and what they said, but I soon came to realise that successfully verifying all of this information would perhaps be impossible.

There are portraits and objects in this exhibition, and alongside these two components are pieces of text that speak to what you call “slippage”. I choose texts in which there is a questioning of fact. For instance, I included an email conversation between me and Han’s ex-husband where I try to clarify the song’s origins. I write to him, and he writes back to say that he’s unsure if the song truly existed — a part of me was disappointed with that response.

There’s another exchange between my uncle and I, and that is a debate about whether my grandfather could have been communist or not. It’s an ongoing debate in the family, and is one of the sticking points of me doing this project. They will say that it’s no longer important whether or not he was a communist, but every time I find a small piece of information that suggests that my grandfather could’ve been an underground MCP member, there is major pushback from my oldest uncle, in particular.

I’ve also included a letter from the archive in the exhibition. The letter is from a mother pleading to the British authorities for her son’s release. In the letter, she writes that her son wasn’t communist and only ran away from the police because he was a young boy and scared of the police. I’m just questioning what happened, and what we recall of what happened.

Also in the exhibition is a piece of text from an interview I did with an elderly man who got deported as part of the Malayan Emergency. I asked him to describe to me the process of deportation, and he describes it in incredibly vivid detail. He could say things such as, “四个男人, 一个铁链” (four men were shackled with a single metal chain). They were shackled at the ankles, and he remembers this in such detail that I kept asking him if he was sure. I interviewed him twice in Zhongshan, Guangdong, and he said that he was really sure. I tried to counter-check his against someone who used to be part of the British Special Branch, and he said no. I presented these two contrasting pieces of information in this exhibition, and I guess what I’m trying to do here is to question both myself and the accepted wisdom about what happened during the Malayan Emergency, and what these foot soldiers on the ground remember of it — that is not in any archive or document.

There’s still a lot that we don’t know, and there’s also a lot we can’t know anymore. I’ve been working on this project for nearly seven years now, and I’ve come to realise that I will not be able to factually verify a lot of the information I gather. Yet as an art maker, how important is that fact? Should it be possible to ascertain the factual nature of this information, how then do I present it in an artistic way?

I don’t know if there’s a specific turning point in this, but I’ve stepped out of the specific silo of photography over the past year, and have begun to explore other ways of making. I’m more interested in a multiplicitous consideration of what I’m looking at and what I’m trying to represent. I know this kind of sits at odds with the fact that I’m about to start a PhD in History. I know that obviously, as an academic and historian, there are ways certain ethical standards and ways in which the discipline works. I may have to separate or find a way to complement the two — the fact-seeking and the art-making.

⁴ One Day We’ll Understand, Sim Chi Yin

UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed, 2018

UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed, 2018

Do you, at this point, see them as being at odds with each other?

I don’t know, yet, how far I’m going to go. At the moment, all of my works are based on documentary evidence. At the moment. I don’t know — in the future, they might not be. But that’s ongoing debate in my own head.

How were the photographed objects in the British Malaya project selected?

There are two types of objects that I’ve photographed. The first group comprise of people’s belongings, and this could be things such as old photographs or old objects. For those things, the interviewees chose what they wanted to show me. But because of how old these interviewees are and how long ago these things happened, they also might not have had many objects left to choose from. I asked them if they had anything from their time in Malaya, or from the time they arrived back in China after the deportation. The interviewees would then go have a look before coming back with these objects. I photograph everything they show me, and I based my eventual selection for both the Esplanade and Amsterdam shows on the visual significance and aesthetics of the image.

The other group of objects I photograph include things, such as the prosthetic leg and the gun, that were in some of the museums in Southern Thailand. These are in the so-called peace camps, which still house some of the ex-communists. I went and asked for permission to photograph in two of their museums. After much persuasion, they allowed me to take these objects out of the museum and to photograph them as still life images.

⁵ One Day We’ll Understand, Sim Chi Yin

2017

2017

What are the sort of factors that feed into how the various exhibitions are displayed, and what roles do the various components (text, portraits and photographs of objects) play? Are there particular components that, you feel, have to remain central across all iterations of the project?

The exhibition I did at Esplanade earlier this year, Relics, featured portraits, objects, and a video installation. I don’t have a macro sense of what I want to do for the next show. It really depends on what the show is about, and how discussions with the curator go. I’ve actually thought about showing the songs alone, or of doing a multi-channel showing of the songs. I’ve collected quite a few songs, and I find that the songs are what move me most. But of course, photography is a main part of my practice – so I feel somewhat wedded to the portraits.

The exhibition in Amsterdam is the way it is because the show itself is meant to take on-board this question of archives and archiving. I tried to think about how this could be done. The portraits had to be there, because I wanted the exhibition to be about these people. On top of that, I really wanted to make use of texts. I feel that texts can make what I’m getting at a little less opaque. The objects are complementary, and maybe not entirely necessary. However, if one looked at portraits and texts alone, the viewer might not have realised that the exhibition tells the stories of people who were guerrilla fighters and who had gone through a war.

The choices of how it displays, again, comes down to experimentation. The Amsterdam exhibition was installed by the curator, Annie Kwan, kind of, by instinct. We discussed it and she Skyped me throughout the process so I could come in with comments about a couple of things. The curator put the works up on two walls that are at right angles with each other, and it’s meant to evoke a sort of scrapbook.

I recently attended in a lab in New York that explored immersive story-telling. Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) are all the fad now, so I ended up making something out of AR or VR for this project. The prototype or sketch for the project was an exhibition where you’d be in the jungle of Malaya. The participant could swipe objects, hear things, and watch some interviews; but I don’t know if I’ll actually make it. At the moment, I’m more drawn to analog. There are a million ways of showing, and it’s just a question about which is the best way. Which method would be the most effective for a particular show or a particular context?

Having worked on this project for close to seven years, how has your understanding of the project or your approach towards collecting information shifted?

The project started out as a very personal search for the story my grandfather, whom we never spoke about. I started off by reconnecting with our village, finding his grave, and just filling out the story of who this man was and what he did. I later found out that he was one of the 30,000 who had experienced this deportation. That really opened up the entire project. I wanted to try to understand not just him, but his generation.

The nature of the project has changed over the years, but how I collect material hasn’t really changed. I still approach the collection of material like a historian would. I still do as thorough an oral interview as possible, and I still collect objects and materials from anyone who has anything to share. The process is still very similar, but of course, I started moving towards collecting things that could translate into making art. I started to collect songs and vernacular photographs.

Part of the reason as to why I’m doing a PhD is that I need much more time for research and this project. It’s become untenable to do this on the side to my work as a freelance practitioner. There are a lot of things I want to do for this project that I haven’t been able to do, and things that I’d like to create that I haven’t been able to create. I’m hoping that I’ll be able to find room to do all of these things that are, as of now, still in my head. It’s both about collecting things as well as making things. I have some ideas as to what I want to do next, but I just need the resources, time and bandwidth to do them.

⁶ One Day We’ll Understand, Sim Chi Yin

UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed, 2018

UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed, 2018

Having seen your shows at both the Esplanade and LASALLE Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) Singapore, I noticed that despite the fact that they explore different subject matters, both exhibitions encourage viewers to slow down.

When you create your works, is this slowness something you’re conscious of working towards?

I don’t know if it’s a deliberate approach across all the projects and bodies of works, but in general, I’m kind of a slow, research-heavy person and so the work ends up being quite dense. The work is demanding of one’s time in that way.

Between the British Malaya project and the nuclear work, I think you can find visual threads that carry through them both. I’ve started working in a slower, more intentional and deliberate manner over the past few years.

I work towards a meditative, evocative photograph, so it does come across as something that can’t be consumed quickly.

It’s very undramatic, and kind of unsexy as well; but maybe it comes from my process of making as well. Each of these pictures took, firstly, a lot of research and negotiation. The actual shooting itself, especially with landscapes, is also a very slow process. Most of the time, these photographs are made with a long exposure and a tripod. The photographs are meant to get people into a state of reflection and meditation.

I’ve been told that people who come to the ICA show can sometimes spend 45 minutes in it, which is quite long amount of time for a show that’s not very large. Someone wrote to me, saying that he had spent an hour in the exhibition just looking and reading. The gallery sitter also sent me a photograph of an old man who had come into the exhibition with a magnifying glass and was looking really closely at the images.

⁷ Fallout, Sim Chi Yin

Nobel Peace Center, 2017

Nobel Peace Center, 2017

This seems like a good point at which to talk about Most People Were Silent, the body of works currently on show at LASALLE ICA.

Comparing this to your work with the British Malaya project, how was the process of photographing something as sensitive as the nuclear enterprise like?

A lot of people were surprised at the difference between the works displayed at ICA and works that I made a long time ago, and some wondered if it the same photographer had created these works. I think the Malaya project is where I evolved most clearly. I don’t see the two bodies of work as being so different, because the moods evoked and colour palettes are very similar.

But obviously, photographing North Korean nuclear sites on the China-North Korean border required a lot of strategy and research. Whilst at the border, I didn’t do anything that a tourist could not, but I did a lot of research as to where the nuclear and military installations were. I was photographing them and because I knew the coordinates for these sites, I was metaphorically trying to see into North Korea. For the sites in the US, I hired a producer who helped me to write for permission and to gain access to them. After that, it was then a matter of going and making the work quickly.

How has the experience of displaying this body of work in Singapore been like, and how has the response been to it thus far?

The response to the show has been good. The curator and gallery sitter have reported a lot more foot traffic than usual. They’ve also mentioned that it has drawn a crowd that doesn’t usually frequent the ICA, and that’s really interesting to me. They also keep laughing about the number of old men who come to the show, but I think that’s because the show was featured in both the Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao. There were people who came to the artist talk with the page from the newspapers in their hands. The gallery sitter has also been engaging everyone in conversation, and has encouraged everyone write comments in the guest book before leaving.

The curator, Caterina Riva, and I made the decision to name the show Most People Were Silent after some discussion. The previous iteration of the exhibition was titled Fallout, so she challenged me to come up with a new title for the show. Most People Were Silent is the original title of my video installation, so when she asked me to come up to with a title for it, that was what I suggested. It ended up being really appropriate title particularly in a Singaporean context, because we’re not known to be very vocal, interested or politicised.

The artist talk was well attended, and the questions were surprisingly good. The questions showed a lot of engagement on the issue. I was concerned that the nuclear issue was very remote for most Singaporeans, but those who came to the artist talk were quite well versed in nuclear technology, energy, and weaponry.

⁸ Fallout, Sim Chi Yin

2018, Most People Were Silent Installation View at Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

Photography by Weizhong Deng

2018, Most People Were Silent Installation View at Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore

Photography by Weizhong Deng

The nuclear enterprise is definitely something that most Singaporeans feel removed from, or do not consider. How has the exhibition opened up conversations with viewers who might be unfamiliar with the issue at hand?

I’ve received a couple of notes from some visitors who say that they had never thought about the issue at all, and how seeing the exhibition or hearing me talk about it opened their minds towards understanding the importance of such a topic in the world that we live in today. I haven’t been able to have long and involved conversations, but there definitely have been a couple of notes that have been sent my way.

Most people were really intrigued by the photographs and where they were photographed. Whilst Singapore isn’t actively involved in the nuclear equation as it were, we were the site of this historic meeting between North Korea and US this year. It really is an issue that should concern all of us, even if we think we’re not in the line of fire, or that fallout can’t get us. If we think about it more broadly, there’s a whole school of scientists who believe that we’ve entered the age of the Anthropocene. These scientists take the date of July 1945, when the first test of nuclear weapons was done, as the first day of this new age. That test released these elements into our atmosphere that weren’t present before. It sounds like something that’s quite far removed from bread and butter issues, but this body of work speaks to those who are interested in where humankind is moving towards.

Having occupied the difference spaces of being a journalist and having read history at university, how have these experiences influenced your practice, and has this influence shifted over time? Where do you see your practice moving towards?

I think you can’t change your makeup, you can’t change your pedigree or where you came from, but I am questioning certain assumptions that lie beneath these disciplines. I have a lot of question marks over certain aspects of journalism; and we spoke earlier about my relationship to history and a reliance on facts. These are things I’m questioning in my head.

As I move into working with oral histories, I think that’s going to become an issue for both the academic work that I’ll be getting into, and my art making. I will still draw on the parts of history and journalism I still feel are useful, such as the rigour for research and certain ethical precepts. However, I’m not sure if it will define the way I make work in the future.

I’m in a place where I’m happily absorbing, learning, reading and growing. I’ll just continue to experiment and see where things go. Obviously, I think that there are many different ways of presenting works, and I do not want to be stuck into one way or another. I’m quite happy to cross disciplines. My friends often say that if I could paint, I probably would’ve been a painter. I don’t want to be boxed in to one or the other. We have an incredibly well-stocked toolbox at our disposal nowadays — there are so many ways of presenting an idea.

For me, the thing that will never go away is the power of the story. There are stories in a lot of the things we’re trying to say; and in the end, it’s all about stories. The power of the story will be central to the kind of work that I continue to produce.

As to how that comes out, I want to leave that wide open. I think that’s what makes it fun. I’m deliberately reading books and looking at works that lie outside of photography. There are certain tropes that have been tried and tested, photographers have used them over and over again. Although they’re still effective, I’m trying to grow and evolve on my own. I’m not sure where this will lead, but I’ll just keep at it, and see where it goes.

Fallout is part of Most People Were Silent at

LASALLE Institute for Contemporary Arts Singapore.

The exhibition will run until 10 October 2018.

For more information, visit ICAS’s website.

LASALLE Institute for Contemporary Arts Singapore.

The exhibition will run until 10 October 2018.

For more information, visit ICAS’s website.

One Day We’ll Understand is part of

UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed.

The exhibition will run until 18 November 2018.

For more information, visit Framer Framed’s website.

UnAuthorised Medium at Framer Framed.

The exhibition will run until 18 November 2018.

For more information, visit Framer Framed’s website.