Sissel Tolaas is a smell researcher and artist. She was born in Norway and is currently based in Berlin. Sissel studied mathematics, chemical science, languages, and visual art. Since 1990, her work has been concentrated on the research topics of SMELL / SMELL & LANGUAGE – COMMUNICATION, within the realms of sciences, art & design and other disciplines. Her research has won recognition through numerous national and international scholarships, honours and prizes. Her projects and research have been presented in several institutions such as: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Fondation Cartier, Museum of Modern Art Berlin and Tate Liverpool. Tolaas has been doing City SmellScape research of and for 52 cities including Amman, Shanghai and Stockholm.

Sissel is exhibiting a work titled eau d'you Who Am I as part of the Light to Night Sensorial Trail. The smell molecules were captured using a special tool, and have been installed into walls of the exhibition space. When asked about artworks and objects that have influenced her, Sissel picked out the works of Marcel Duchamp, Piero Manzoni, Buckminster Fuller and the space shuttle, Sputnik 1.

Sissel is exhibiting a work titled eau d'you Who Am I as part of the Light to Night Sensorial Trail. The smell molecules were captured using a special tool, and have been installed into walls of the exhibition space. When asked about artworks and objects that have influenced her, Sissel picked out the works of Marcel Duchamp, Piero Manzoni, Buckminster Fuller and the space shuttle, Sputnik 1.

Credit: Sissel Tolaas

¹ 50 cc of Paris Air, Marcel Duchamp

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1919

I found your selection of Duchamp’s work intriguing, because there are many parallels between this work and your own practice. With 50 cc of Paris Air, Duchamp sought to capture something invisible, such as Parisian air. In the same way, your work with smell also deals with the invisible.

When you set out to work with smells, urban environments or sentiments, is there a particular philosophy that governs how you operate?

What connects my work with that of Duchamp are the irony, the playfulness and a certain amount of strategic nonsense. We both favour a more intellectual, concept-driven viewing by rejecting pure ‘retinal pleasure’. 50 cc of Paris Air represents all of this very well. Duchamp was the first to experiment with living and dealing with contradiction, like those whose jobs are to put out fires in oil wells. His metier was everyday objects that have been taken out of their usual contexts.

Similarly, real life and being alive are my metier.

My work focuses on amplifying invisible reality. I would call myself a practical philosopher. When I work, I always begin with the physical experience of smelling. Smell nerves are connected to the brain without intermediate processors. My background in organic chemistry, together with specific technology, then allows me to capture this air. By investigating its individual particles or smell molecules, I can understand and use them to clearly communicate the issues I am interested in.

My works are so simple, yet so complex. The processes behind my works are similar to Duchamp’s in the sense that the creation of the works might be rudimental, but the final experience is like a breath of fresh, complex air.

² Artist’s Shit (Merda d'artista), Piero Manzoni

Tate, 1961

That ties in really nicely to your selection of Manzoni’s work as well. When it comes to executing a complex concept simply, Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit (Merda d'artista) did exactly that as it challenged viewers’ perceptions of what art could be. Although viewers were shocked that cans of shit could be sold as art, it was revealed that they actually contained plaster. It brought up questions of whether it was important that art did what it said it would on the can, or if the audience’s perceived experience was more significant.

Yes, exactly. My work is not just about the invisible matter, but it also emphasises how this is communicated and perceived. In the case of Manzoni, you have all these questions about authenticity, veracity, expectations and reality.

More importantly, I chose this work because I wanted touch on our prejudices towards certain smells. We tend to categorise smells, and to consider some smells undesirable and unsavoury. This was something Manzoni emphasised in this work too. There’s nothing more natural than human faeces. At the end of the day, everything goes to shit.

This works also draws out the relationship between art production and human production. In my case, I consider breathing and air. I capture a breath, analyse it, and give it back in various forms including artworks such as eau d'you Who Am I.

It’s interesting that you bring up this hierarchy of smells. There are smells that people associate with the work of perfumers — scents that are pleasant and desirable. On the other hand, there are smells that people find disgusting. A lot of your work deals with the urban environment and people’s lived experiences, so what do you make of this distinction between a “high-brow” and an everyday smell?

We are all born neutral and curious. From there, we begin exploring the world using all five of our senses. We are constantly eating, smelling, tasting, touching, listening and talking. In doing so, we are also constantly recording and learning. In these early stages, we are sometimes told by older figures of authority that some smells are good and that others are bad. We do not get the chance to understand a smell for what it truly is. This information about a smell and its categorisation is then gathered and stored. It stays with us till we die. I try to work with young people as much as I can, because I find that the older we get, the more comfortable and set in our own ways we are.

There are also moments in life when beauty or trauma is experienced. If a smell featured prominently in those moments, one’s perception of it might remain fixed for a long time. This is not to say that change is impossible, but that it has to be a concerted effort. To become neutral again, one need to remove these preconceived prejudices. It almost is like a smell detox or smell rehabilitation.

As I said earlier, my work is about real life and being alive. As such, it has been essential for me to understand just how important neutrality is. I don’t operate with any type of hierarchy. A smell is a smell, and all of them deserve my attention. I got rid of all of my prejudices early on in my practice. Everything has a smell and everyone experiences smell very differently. My work is about making this a part of everyday discourse.

The air that we breathe in everyday contains invisible molecules, and these particles can give us information about our surroundings beyond what is visible to the naked eye. These particles can be found in faeces, in sweat, in garbage, and in perfume. I decontextualise a smell so as to make it “neutral”, and to challenge audiences to approach these smells with the most sophisticated equipment they own — their noses.

Unfortunately in most cultures, all of that information has been placed into the two categories of “acceptable” and “not acceptable”. As a result, most of us live in societies that sanitise, sterilise and perfume to extreme measures. This has to change. If we do not start to care for our sense of smell, we soon will have none at all.

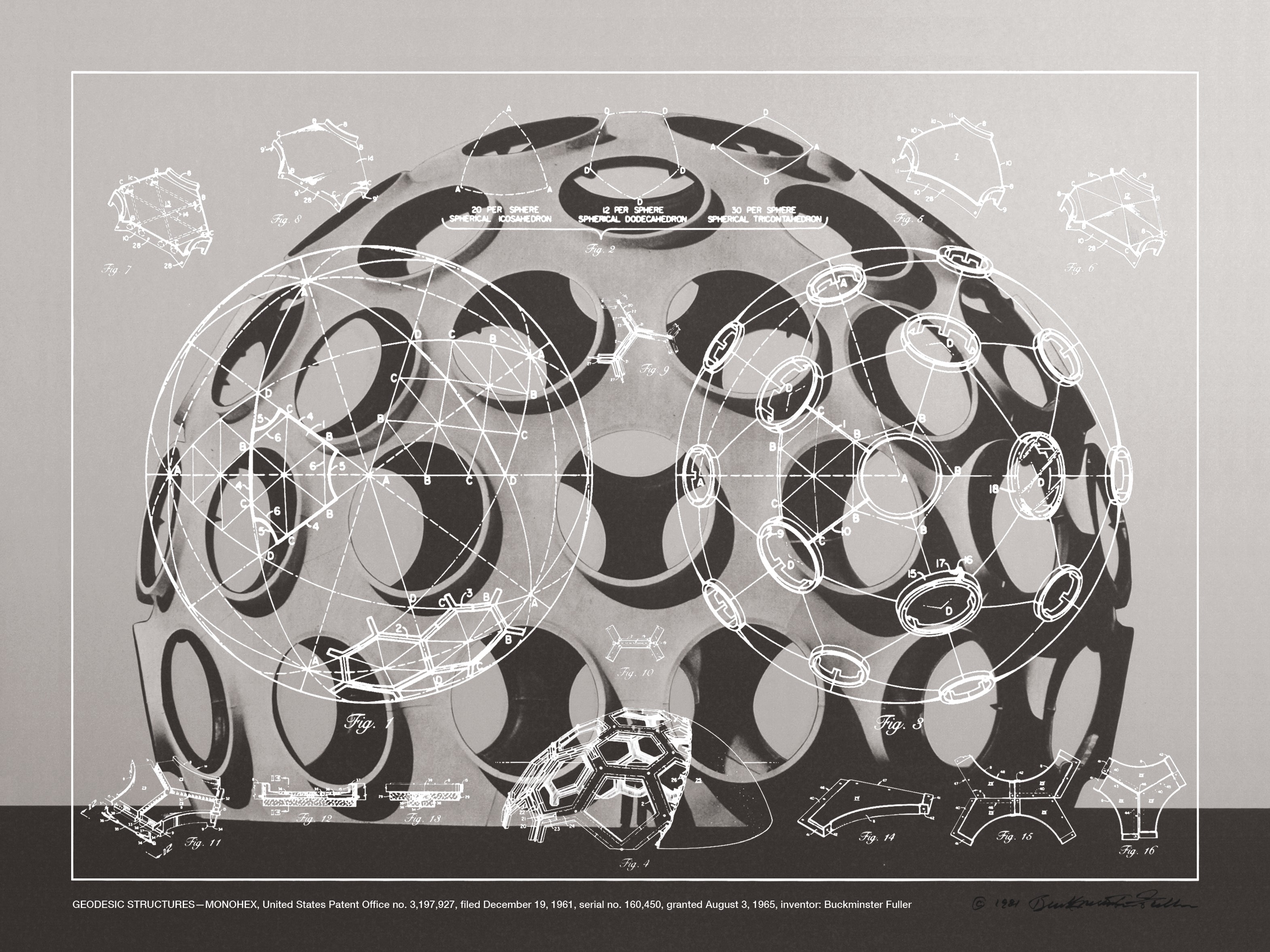

³ Geodesic Structures - Monohex, Buckminster Fuller

Edward Cella Art and Architecture, 1981

I wanted to talk about your background in chemistry as well. Coming to your selection of Buckminster Fuller’s work, he was a multi-hyphenate creative and scientist who worked across architecture, design, science and environmentalism. Throughout your practice, you’ve also drawn upon a variety of philosophies, methodologies and ideas. Could you tell us more about your own relationship to Fuller’s work, and why you feel it important to reference multiple disciplines?

When you’re interested in life and being alive, you have to know as much as possible about everything. My interests were and are unlimited. When I first began studying various disciplines simultaneously, my hope was to identify my core interest in doing so. I drew from whatever, whomever, or whichever discipline would inspire me to do this. I did not know where I was going but I knew I was going somewhere.

On top of my background in organic chemistry, I’ve learnt a great deal from biology, neuroscience, psychology and art. I’ve always been inspired by those who dare to approach issues with interdisciplinary perspectives. Buckminster Fuller dedicated his life towards working for the betterment of all humanity, and I try to do that with my work too. In order to do so, I can’t just rely on chemistry. Like him, I place my ideas and inventions in ‘artefacts.’

Throughout my practice, I have sought answers to my questions, both alone or in collaboration with those who work in other disciplines. The world’s problems need to be approached with the perspective of a generalist, rather than that of a specialist.

⁴ Sputnik 1, Academy of Sciences of the USSR

The Museum of Flight, 1956

That idea of bettering humanity segues nicely into your selection of the space shuttle, Sputnik 1, for our conversation. Its progress captivated audiences worldwide, despite the geopolitical tensions of the time. What is your own personal connection to the shuttle, and how do you see it speaking to your practice?

When I was younger, I wanted to be an astronaut. I wanted to look down on Earth from outer space to figure out where I could place myself. It was wishful thinking that I could have such a great impact on the world, but I saw myself as a sort of Sputnik 1 very early on. If you consider the ambition of the project and the scientific advancements it accelerated, Sputnik 1 was of tremendous importance for all of humanity. It parallels, in many ways, my own ambition with my practice. I am the only one in the world that works with smell in this way, and it is a huge responsibility.

Sputnik was the beginning of everything, and was pioneering in its own right. It was the first satellite, and the beginning of man’s conquest of space. Sixty years later, it’s still amazing to think of the impact this one small object has on us all. I think of Sputnik 1 as one of the world’s greatest inventions, and I do wish it was one of my inventions. It’s a small, silver ball. With my practice, I see small invisible molecules as having this sort of potential. If we understand these molecules and use them correctly, they could have tremendous impact on humankind as well.

I did a project for the 7th Moscow Biennale with the Russian space agency last year. The work, titled Sputnik_60 Memory Game, comprised of sixty different balls, each carrying a different stored memory of the past, present and future.

Personally, I associate smells with individual experiences. What a smell triggers or means might be very different from one person to the next. Do you see your work with scents and smells as mediating vessels for memories that your viewers might have?

When speaking about my work I prefer using the word “smell”, because it is more neutral and contains both positive and negative connotations.

All of our senses work in tandem with each other. Although our sense of sight is the predominant way with which we experience the world, we glean information about our surroundings most efficiently from our sense of smell. Smells are used constantly, consciously or subconsciously, to as a means of communication between plants, animals, and human beings. It is more closely linked to memory than any other sense, and is the most effective trigger of memory and emotion. Emotions and emotional intelligence are essential to being human.

It is amazing to challenge people to use their noses to understand the world. Through my work, I offer new methods with which one could use to approach reality, different to those learned from watching screens. In facilitating a more comfortable relationship with smell, I think my works have the potential to change my audience’s mood. They provide a more positive or optimistic perspective on the issues we face today. There is a playfulness about discovering the world through smell and to inspiring new modes of interacting with others or our surroundings.

When asked to use their noses for purposes other than breathing in or out, my experience is that people all over the world become both really challenged and engaged. In those moments, it does not matter what they actually smell. What matters is that they rediscover their surroundings — be it other human beings, places, or even the city itself. When people perceive these messages through the sense of smell, they really internalise this information.

⁵ eau d'you Who Am I, Sissel Tolaas

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: National Gallery Singapore

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: National Gallery Singapore

Having previously done a residency with the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA), how did your time doing research into urban neighbourhoods in Singapore and their smell profiles help and influence the process of creating eau d’you Who Am I?

For the project with NTU CCA, Incomplete Urbanism, I was interested in Chinatown and the legacy of William Lim. That project explored the social aspect of living in cities, and touched on issues about having neighbours and the importance of tolerance. Different smells can emit from our neighbour’s flat, so how do we react to these smells? Part and parcel of living in the city is this beautiful notion of tolerance and appreciation. I mapped the neighbourhoods around two buildings in Singapore for this project, namely Golden Mile Complex and People’s Park Complex. For this project, I built up substantial archives of recorded smells, primarily in the above mentioned areas.

On top of this, I was constantly exploring the city’s diversity with my own nose. Regardless of a project’s scale, I always use the same methodologies and techniques. With my work, fieldwork is absolutely necessary. When I go out, I identify smells first with my nose and later with my technologies. I collect data using specific devices that allow me to record sources of smells. The recorded smells are then replicated using chemical compounds.

By the time I started on the project for the National Gallery Singapore, I already had a pretty good idea of the various neighbourhoods in Singapore. This work was informed by some workshops I did with young people who live in Singapore, so when they were listing out particular buildings and spaces, I had a good sense of where these places were. The project focuses on the notion of identity, particularly questions around what makes us who we are, what makes us unique, the external and internal influences that contribute to a sense of confidence and self. In short, you are what you breathe. We held several workshops and did fieldwork to explore issues that were important to these young people. It was really interesting to see that many of them were drawn to similar sites, places and issues.

The idea of visitors having to lean towards the wall and draw close in order to get a whiff of these scents is also an incredibly intimate experience. Was there something you were trying to approximate or create by inviting audiences to come closer to the work?

In my work I am interested in a smell’s narrative, and in placing as little emphasis on the other senses as possible. In the case of eau d'you Who Am I at the National Gallery Singapore, yes, viewers are able to see the wall surface. Yet nothing happens until they actively engage with it. Viewers aren’t usually allowed to touch these surfaces because museums and art institutions have particular restrictions in place. As such, visitors are often reluctant when invited to touch these surfaces, let alone smell them. But as soon as they overcome this initial barrier, they can’t get enough of the work. That tells us a lot. What are we denying visitors to these institutions by preventing them from exploring or experiencing works of art through all five senses?

Here, the wall is an invisible page and becomes the metaphor for skin — the skin of a city, or the skin of a person. The visitors have to touch the wall in order to activate the smell. This work takes a microscopic look at a city, and makes this perspective accessible to a general public.

Singapore is incredibly complex and dense. It is a city associated with shiny veneers, cleanliness and wealth. It’s so hard to get underneath the city’s skin if you’re not doing it in a professional manner. This project is also an homage to patina and traces of life and being alive. It’s like going through invisible pages in an invisible book — you have to start at the beginning, and you might end up at the beginning again. I am very thankful that the National Gallery Singapore gave me the opportunity to show these invisible pages in a different light. It is unorthodox, but what viewers experience when encountering such artworks is important. It’s about looking beneath the surface and beyond the superficial. Hopefully, it will challenge viewers to approach the world around them in a different way, and institutions to further expand their definition of art. Life is everywhere and sometime we just have to stop and recognise it.

⁶ eau d'you Who Am I, Sissel Tolaas

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: National Gallery Singapore

2019, Installation View at National Gallery Singapore

Credit: National Gallery Singapore

eau d'you Who Am I is part of the Light to Night Sensorial Trail.

The showcase will run until 31 March 2019.

For more information, visit the Light to Night website.

The showcase will run until 31 March 2019.

For more information, visit the Light to Night website.