When you do a simple Google search of the artist Yunizar and his practice, often critics describe his practice as being inspired by vignettes from his everyday life. Yet, what one considers to be vernacular or everyday can differ greatly depending on the cultural, social, economical or political context within which one is placed. In a recent exhibition, Yunizar’s works were placed alongside the works of artists both emerging and established, and from all around the wider Southeast Asian region. We meet with the curator of the exhibition, Syed Muhammad Hafiz, to discuss one of Yunizar’s work in greater detail.

Syed Muhammad Hafiz is currently an Independent Curator and a PhD candidate with the Faculty of Arts and Social Science at National University Singapore. He was previously with National Gallery Singapore from 2012 to 2018, and the Singapore Art Museum from 2009 to 2010. His long-standing interest in the socio-political histories of the Nusantara has seen him being involved in various cultural projects over both sides of the Causeway over the past decade. Recent projects in Malaysia include being the lead writer for Hati & Jiwa Vol. 3, a publication for one of Malaysia’s top collectors, Zain Azahari, and curating for Segaris Art Centre.

Syed Muhammad Hafiz is currently an Independent Curator and a PhD candidate with the Faculty of Arts and Social Science at National University Singapore. He was previously with National Gallery Singapore from 2012 to 2018, and the Singapore Art Museum from 2009 to 2010. His long-standing interest in the socio-political histories of the Nusantara has seen him being involved in various cultural projects over both sides of the Causeway over the past decade. Recent projects in Malaysia include being the lead writer for Hati & Jiwa Vol. 3, a publication for one of Malaysia’s top collectors, Zain Azahari, and curating for Segaris Art Centre.

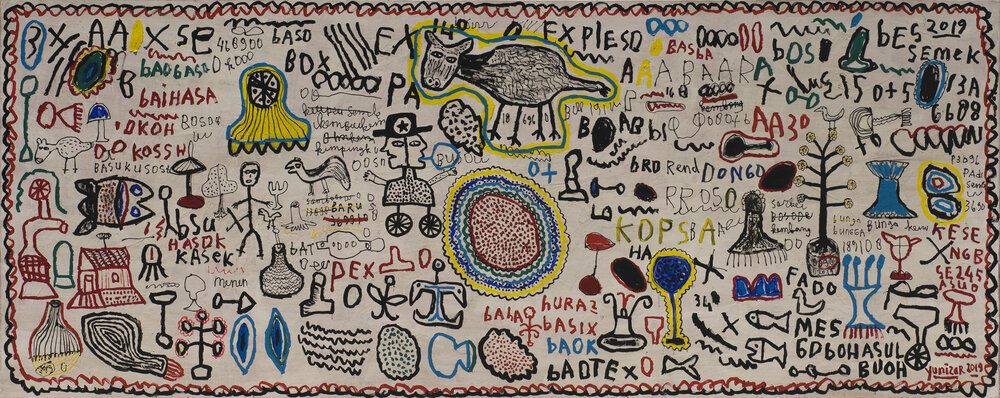

¹ Untitled, Yunizar

2019

2019

WITHIN, AROUND AND BEYOND LANGUAGE

Syed Muhammad Hafiz (SMH): Having followed his practice for quite some time, the thing that strikes me about Yunizar’s work is how it touches on ideas of rationality and language. When I use the term “language”, I use it in the broadest sense of the word. I mean “language” in terms of how one would read an artwork, and also “language” in the literal acoustic sense. When you come across articles that have been written about Yunizar, the writings usually discuss how his works defy rationality and the structure or form of language. As such, I'm inclined to view it within these frameworks.

For me, Yunizar’s work has that additional layer of humour — which I think is a good entry point into an artwork. Of course, that’s my bias. Different things appeal to different viewers. Having said that, I don’t mean to say that all of Yunizar’s works are humorous. This work, Untitled, is a little comical and you see some naivety in the form of childlike doodles. As writers or art historians, we can sometimes describe an artwork as drawing upon everyday life or touching on matters surroundings one’s everyday life. However, we might not share the same idea of what the “everyday” means. In Yunizar’s case, for example, his everyday is a particular setting in Jogjakarta. That's where the artist is based right now. However, he also has his roots in Sumatra, which is of course presents a different kind of reality.

Yunizar is one of the very few artists I know that push the button. There are certain works where you see an artist making a direct effort to push the button. For Yunizar, you don't see the effort, but you know he's pushing the buttons. He does this through certain compositions, certain strategies, and using certain strokes or visual images images. A previous exhibition he did titled Jogja Psychedelia was all about flowers. It is just a single, simple idea — flowers. We know that almost every great modern artist has depicted flowers in their practice in one way or another. This has been done through still lifes, for example. Yunizar used flowers to carve out a bigger narrative about Indonesian art. Not many artists can do that.

Yunizar pushes the buttons in various ways. One of which is to defy how a curator or an art historian reads an artwork. Like it or not, writers, creators, or art historians — we all have our biases and our own cultural contexts. We are formed by our experiences, and we bring them into how we experience exhibitions or artworks. Particularly in the context of Indonesian art, there has been a tradition of writing that groups artists together in schools such as the Jogjakarta School, the Bandung School, so on and so forth. Given this backdrop, when you encounter someone such as Yunizar, the question often is: where does he fit in? What do I do with this? He comes from a particular tradition, and is based in this particular locale, but he creates something that denies you that easy, first level of reading. If you take a closer look at his biography, what he's about, or his character, it doesn’t get any easier to place his works within that context. Before you know it, you’re taking that initiative or effort out to understand where the artist is coming from. It lures you in.

² Routine, Fadilah Karim

2019

³ Royal Abstraction, Jai Abu Hassan

2020

2019

³ Royal Abstraction, Jai Abu Hassan

2020

GENERATIONS OF GENERATION

SMH: Yunizar is a senior, established artist that younger, emerging artists often look up to. This is particularly in the context of Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia — the art scenes I’m most familiar with. When artists enjoy a particular level of stature or position, it doesn't necessarily translate into the energy required to work on something new. This is not to say that they have to, of course, but some artists get comfortable. With every new work and with every new series, Yunizar is always asking new questions. I have not spoken to him, and I didn’t speak to him in the process of curating this show, but I think this drive is something that is incredibly admirable. At a market level, Yunizar’s works are still high in demand and there must be a reason for this. It must mean that his works are consistently good, and collectors still see the energy in his works.

This show is about generating dialogues, and this can be between the artists — regardless of where they’re at in their practice. Within this exhibition we have works by younger artists such as Fadilah Karim, an emerging Malaysian artist, along works by Jalaini Abu Hassan, an established artist and respected art educator at UiTM.

For this exhibition, the main narrative that got me excited was education. I’m not referring to art education in particular, but the transmission of knowledge. I'm doing my PhD right now, so I’m very interested in how knowledge is transmitted and how art curriculums are put together in countries such as Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. One might come across writings about a country’s art scene that might seem simplistic or reductive. When we talk about the Jogjakarta school or the Bandung school in Indonesia, for example, what do we mean? The art scenes in both places are incredibly different. There is a reason why students tend to flock to one place over another to study art, practice art, or set up their studios. However, how do we begin to outline or define these terms?

When I was putting this exhibition together, I wanted to put together something that brought artists of very diverse backgrounds together. Perhaps subconsciously, I was trying to break that notion altogether and the best way to do so is to just show that these artists are not a monolith. As writers or art historians, it can often be easier to write about things when we categorise them or begin identifying patterns and trends. I’m sometimes guilty of this too. At the end of the day, I wanted this show to be an exhibition of or testament to each artist’s agency.

EXHIBITION MAKING AS RECIPROCITY

SMH: There’s a lot of unseen labour in curating a show, and that’s a term I’m still grappling with. When you curate a show, it’s about creating a bridge between the artist’s intentions and the general public. When I say unseen labour, I don’t mean visiting the artist’s studio or getting to know them. For me, that’s the least you should do as a curator. The unseen labour is taking the time out to really think about how you can do justice to what the artist wants the public to learn. That’s absolutely crucial. Of course, you can’t control the public opinion. However if an artist is unable with the exhibition or my curation, I see a certain degree of failure there.

When I first started curating awhile ago, the idea of curating an exhibition was something that was still gaining ground. People didn’t necessarily know what curating meant. Now, we’re at a stage where the idea of curation has become incredibly popular. What I enjoy most about being a curator is the fact that I am in a position where I can actively learn from artists. That’s the baseline for me. Learning from an artist, hanging out, and just talking. It is about reciprocity.

There are moments where you think to yourself, am I including this artist in this exhibition because we are friends? Maybe the work isn’t as good as you think it is. Having said that, I’m not one to shy away from that level of familiarity or good energies. This is just one way to curate a show. There are shows I’ve curated where I don’t know the artist personally either. At the end of the day, it is important to take a closer look at how the art world operates. Everything is relational.

GENSET was an exhibition that ran at Gajah Gallery until 19 February 2020.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.