Tang Ling Nah (b. 1971, Singapore) uses drawing, book art, installation, performance and video to explore urban transitional spaces as communicators of life stories. A recipient of the National Arts Council’s Young Artist Award (Art) (2004), the Juror’s Choice in the Philip Morris Singapore-ASEAN Art Awards (2003) and the Della Butcher Award (2000), she has represented Singapore in the 2nd Singapore Biennale (2008) and exhibited at the 11th International Architecture Biennale in Venice (2008).

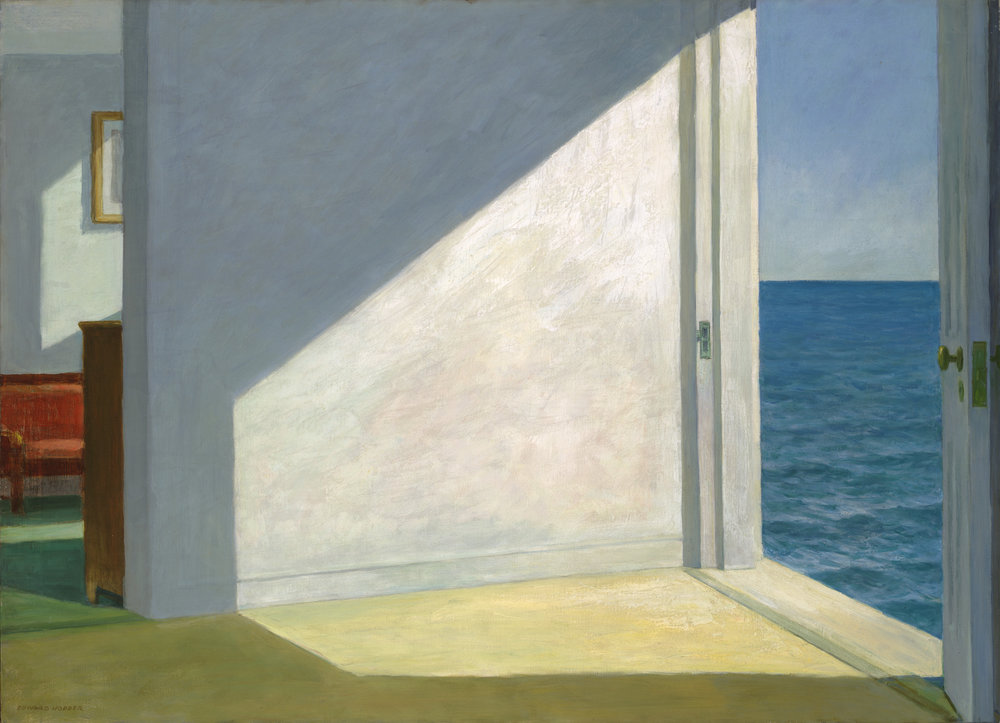

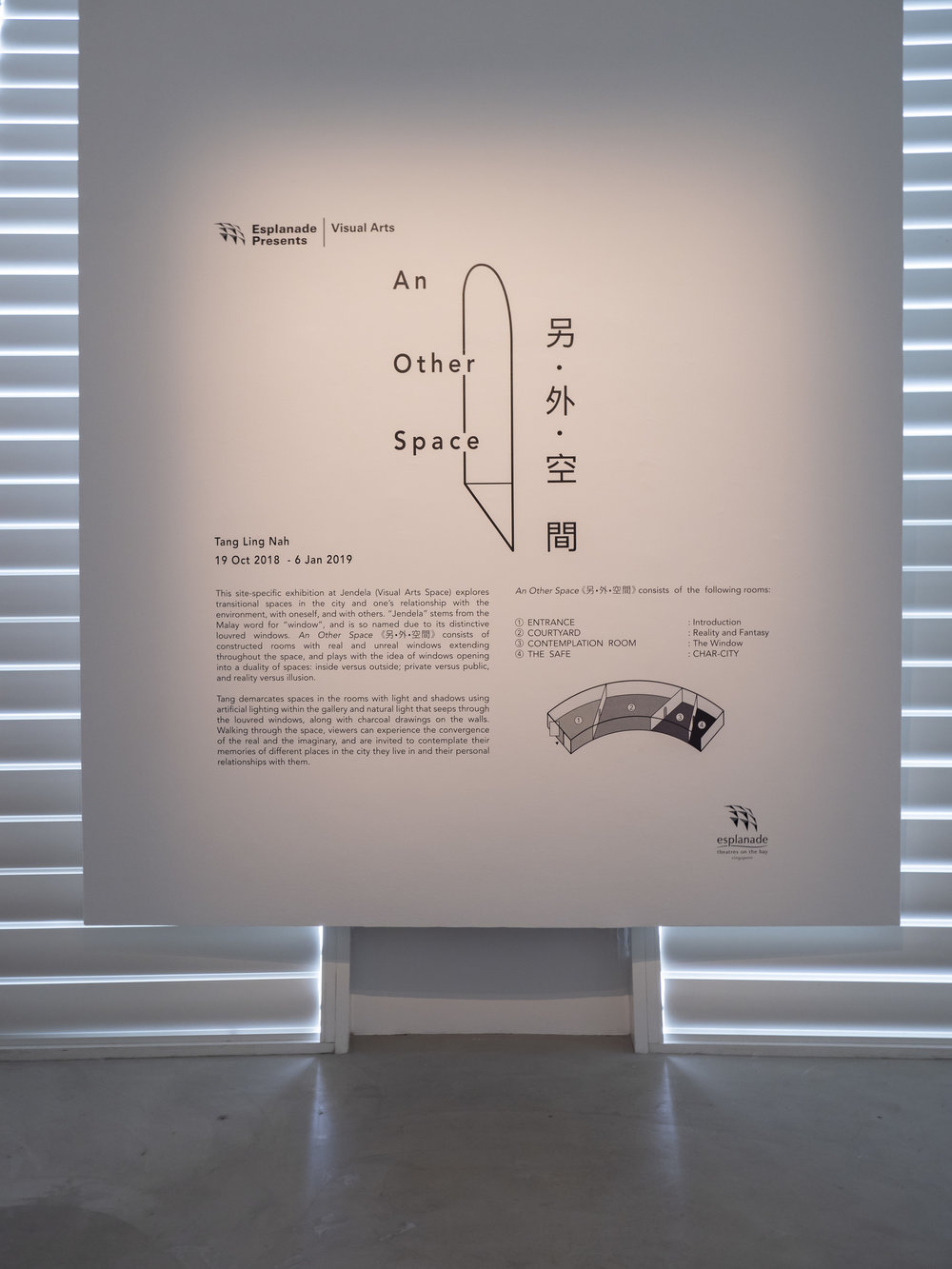

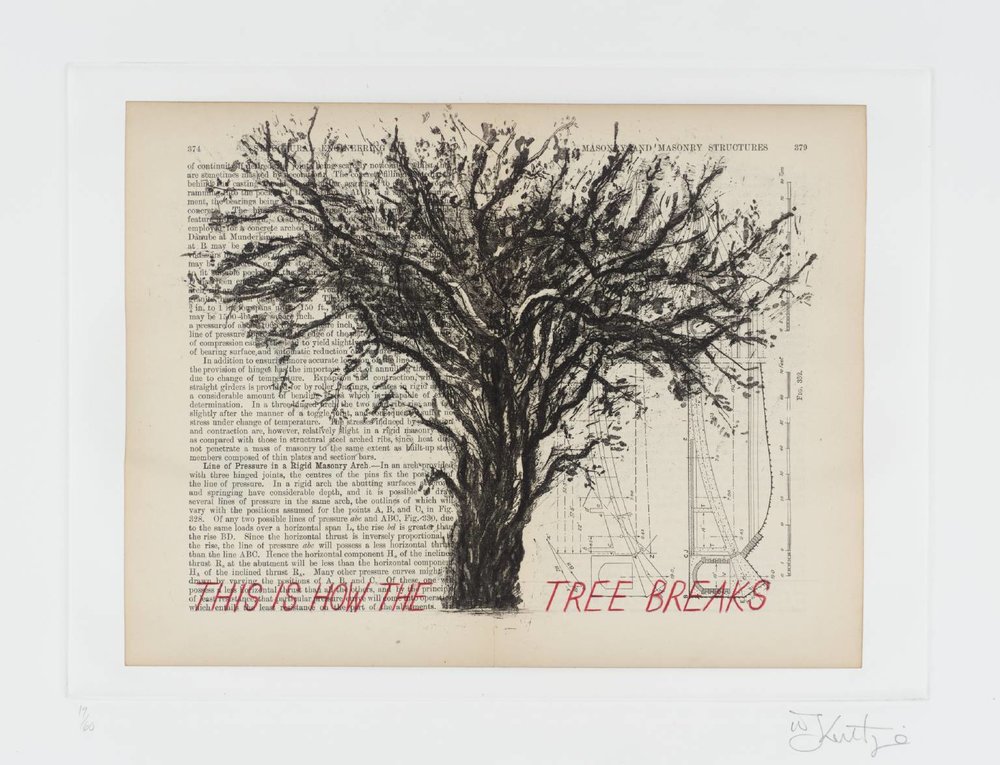

Currently on at the Esplanade’s Jendela (Visual Arts Space) is the exhibition, An Other Space《另•外•空間》. In conceptualising this exhibition, Ling Nah drew upon the works of artists such as Edward Hopper, Richard Serra, Robert Longo, and William Kentridge. Ling Nah was also inspired by the Rei Naito’s site-specific work Matrix, and the comics of Jimmy Liao 幾米. We meet with Ling Nah in her studio and home to chat more about her current exhibition, and the trajectory her practice has taken.

Currently on at the Esplanade’s Jendela (Visual Arts Space) is the exhibition, An Other Space《另•外•空間》. In conceptualising this exhibition, Ling Nah drew upon the works of artists such as Edward Hopper, Richard Serra, Robert Longo, and William Kentridge. Ling Nah was also inspired by the Rei Naito’s site-specific work Matrix, and the comics of Jimmy Liao 幾米. We meet with Ling Nah in her studio and home to chat more about her current exhibition, and the trajectory her practice has taken.

What drew you towards picking out the artworks that you did, and what sort of things were going through your mind when conceptualising An Other Space《另•外•空間》?

When Esplanade invited me to do this exhibition within the Jendela Visual Arts Space, I was immediately drawn towards thinking about the physical space. I’ve worked on shows within the Jendela space before, the first being a show I co-curated with Michael Lee in 2003 titled Cinepolitans: Inhabitants of a Filmic City. It was through curating that exhibition that I came to realise just how unique the physical space of the Jendela is. It’s a curved space with louvre windows, and that’s how the Jendela got its name — jendela being the Malay word for “window”.

It’s actually quite a challenging space to work with, so I thought it was important to get architectural advice throughout the planning process. I was able to draw or sketch out what I wanted the space to look like, but I needed someone with architectural expertise to liaise with the contractors who were building these partitions. When I create site-specific installations, questions about space are always very important to me. I wanted to use these partitions as a way to seal spaces off.

I was also thinking about a work I did in the Esplanade Tunnel. In 2010, I worked on an on-site installation titled The World Outside 《外面的世界》. Essentially, I presented a series of charcoal drawings on walls. As compared to the Jendela space, the Tunnel sees very high pedestrian traffic everyday. I was thinking very much about the progression of space. With the Jendela, I was interested in the interior space itself, but also the outside world, which was brought into the space through these large windows. Ironically, I made sure that false walls were constructed so that all the windows, except one, would be covered up. In a way, it makes the presence of that single window all the more pronounced.

Yale University Art Gallery, 1951

² Torqued Ellipse, Richard Serra

Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, 2003 - 2004

A couple of the artists that you picked out for this interview, such as Edward Hopper and Richard Serra, are known for their explorations of light and shadow within a space.

You spoke about the progression of space earlier, and I wanted to come back to that. When one comes into the exhibition, they’re brought through spaces that vary from artificial light (The Courtyard), to natural light (Contemplation Room), and even complete darkness (The Safe). Why was that progression important for you to create?

Whether I draw or play around with actual lighting methods, most of my works are explorations into light and shadows. With An Other Space《另•外•空間》, I wanted to challenged myself by drawing with light. By having the spaces move in a progression, I want the audience to first see an illusory world. In a way, I hoped that audiences would first encounter my perspective of the city through transitional spaces, such as windows.

The entrance of the exhibition serves as an introduction to the entire space. In particular, the drawings in The Courtyard might remind audiences of spaces in the city that they’ve encountered, passed by or have walked through.

The drawings depict fragments of the city, and one is simultaneously brought back into their own memory whilst being exposed to the artist’s perspective.

Within The Courtyard, I also wanted to include lines of light that visitors could interact with. Because of the louvre windows, these horizontal lines of light usually flood the Jendela space. However by constructing false walls for this exhibition, these natural lines of light have been blocked out.

Prior to setting this exhibition up, I spent a day observing how the light changes within the space throughout the day. Daylight looks very different to evening light, and personally, I prefer the space in evening light — when the lights from outside are reflected into the Jendela. With daylight, the light that filters through the louvre windows is quite faint.

Teshima Museum, 2010

Incorporating natural elements into an artwork is something that Rei Naito explores in her work, Matrix, as well. Many exhibitions have been put up in the Jendela before, but not many of them have considered bringing the outside in, so to speak, in such an intentional way.

Your works have explored, in many ways, the idea of a city and its spaces. Why is that something you keep coming back to, and what about the city intrigues you?

I think of the city, obviously, because I live in these urbanised spaces myself. I’ve spent most of my life living in flats and surrounded by buildings, so I think these architectural spaces have always intrigued me.

In particular, I’m interested in the transitional spaces we often overlook. Even though they are transitional in nature, I always think of them as spaces of great possibility. I know that’s vague, but I often think of this empty space in the CityLink Mall. It a space between City Hall MRT and the Esplanade, and I think the public has taken advantage of its large space by using it as a space for gathering, dancing, and even sleeping. It would be great if more of such transitional corners within Singapore were activated or energised by the people. I think there is a lot of warmth in that activity, and I find that my charcoal drawings similarly bring out that element of warmth.

When one thinks of a city, one sometimes associates it with colours and sound. Instead, what your work does is to encourage viewers to slow down in a fast-paced environment.

There are similar dualities you explore in An Other Space《另•外•空間》as well, especially when it comes to juxtaposing the illusory with reality. Tell us about why you included these elements of illusion in the work.

I work mainly in black and white because I find colours distracting. It is difficult to pay attention to these spaces with colour.

I wanted the viewer to imagine, and to use their imagination. All of the things I draw could, potentially, be all around us. But many city dwellers are either moving too fast or caught up with their phones. As a result, they miss out on the details in their surroundings. It really is as simple as noticing a small plant growing out of the corner. In the context of Singapore, I think of alleys and corridors as interesting architectural spaces. Coming back to the example of the empty space in CityLink Mall, these spaces are real and can be used creatively.

⁴ An Other Space《另•外•空間》, Tang Ling Nah

2018, Courtyard Installation View at Jendela Visual Art Space

Photography by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

2018, Courtyard Installation View at Jendela Visual Art Space

Photography by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

Immediately after The Courtyard, viewers are confronted by a bench and a window in the Contemplation Room.

Well I wouldn’t say it was done to shock the viewer, but I think it was a transition that I felt necessary. The difference between The Courtyard and the Contemplation Room is quite stark, actually, and I wanted to bring people back to reality with that contrast. Hopefully viewers see my point through the juxtaposition of the imagined versus the real in these two rooms.

The bench encourages the viewer to pause, to sit, and to look outside at the city around them. Previously in The Courtyard, the viewer looked at fragments that, perhaps, reminded them of the city. When they then come into the Contemplation Room, they actually look at the city itself. It is, of course, up to the audience to take the cue. Despite living in a city, it’s quite ironic that many of us don’t look at or observe the city much.

I also chose to leave that particular window open because it looks out onto a large tree. Coming to the end of the space, I thought it was a good point at which to encourage viewers to think both about the city that lies within their imagination and the city that they actually see.

Right after the Contemplation Room, viewers come face to face with a curtained partition. Having to push past a black curtain to get into a room, the expectation is often that the room houses a video work or a light projection.

Instead of that, viewers are faced with a sculpture made out of charcoal. Where previously the material was insinuated through the charcoal wall drawings, we now see it face to face. Why was that the endpoint, so to speak, of the spatial progression; and why create a sculpture out of your medium?

I think charcoal, as a medium, is often overlooked. It’s a material that many art students are familiar with starting art school, because its used in sketching and live drawing classes. After that, many artists don’t really think of charcoal as a medium anymore. I worked with oil and acrylic for my diploma, but did a live drawing workshop whilst doing my undergraduate degree. The instructor left it to us to decide on our medium, and that was when I thought I should go back to basics — charcoal. As I continued working with charcoal, I realised that my works were becoming increasingly architectural. That was when I started to seriously consider charcoal as my main medium.

It is a very simple medium — it’s just burnt wood — but, it can form a city.

By drawing with charcoal, I’m able to create all of these architectural spaces. In the Hokkien dialect, charcoal is also referred to as orh ghim (black gold).

With the final sculpture, I wanted everything that viewers had seen in the previous few spaces to all come together. All the charcoal used to create the final CHAR-CITY work was charcoal that I had used to draw the illusionary city in The Courtyard. In a sense, it was my way of venerating the charcoal. That’s why I tried to create an environment that would give the impression of a sacred space. The sculpture is placed higher than eye level so one would have to look up in order to see it. I wanted to suspend the sculpture within a blackened space for a very dramatic effect. Because of this, I had many discussions with the Esplanade’s technical team, and it was their idea to hang and light it in this way.

⁵ An Other Space《另•外•空間》, Tang Ling Nah

2018, Entrance Installation View at Jendela Visual Art Space

Photography by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

⁶ An Other Space《另•外•空間》, Tang Ling Nah

2018, The Safe Installation View at Jendela Visual Art Space

Photography by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

2018, Entrance Installation View at Jendela Visual Art Space

Photography by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

⁶ An Other Space《另•外•空間》, Tang Ling Nah

2018, The Safe Installation View at Jendela Visual Art Space

Photography by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

As compared to the rest of the room, the sculpture is rather small. Was there a reason for that?

I felt that it would have more impact at the size it is now. The curators at the Esplanade did ask for a bigger sculpture, but I don’t think it would have worked. If I had made a larger sculpture, I think it would have lost its importance or its prominence within the space.

As it is, the contrast emphasises the presence of the sculpture and draws people in for a closer look. I don’t really know how to explain it — but I don’t think it can be any larger, physically. It’s not a matter of not having enough charcoal to create a larger piece, because I have a lot of charcoal. But I think a larger sculpture will not have the same city-like silhouette.

⁷ Untitled (Men in the Cities: Ellen), Robert Longo

The Broad, 1981

Coming back to your relationship with charcoal, I think many people know you best for your works in charcoal. What was it about the medium that drew you towards using it time and time again?

When I first began to use charcoal, I just wanted to go back to basics and to play with chiaroscuro. As I worked with charcoal, I realised how flexible and tactile it was as a medium. I was intrigued by the touch of charcoal, and how it works on different surfaces. That’s why I like working on walls as well, because you can’t really predict what you’ll get at the end.

A lot of people think it’s a shame that the work has to be wiped off the wall later. There are definite pros and cons to this, but I like working on walls because of its texture. Drawing on walls can sometimes reveal what’s underneath as well, especially if these walls have history. I enjoy the mark-making ability of charcoal.

Walls are incredibly flat surfaces that sometimes emphasise the two-dimensionality of a work. Instead, your works emphasise perspective and depth. Why push a two-dimensional surface towards three-dimensionality?

I do try to create perspective and depth through tonal elements so that illusions can be created in a trompe-l'œil fashion, and that viewers can feel like they’re a part of the created space. Because of that, I don’t include figures in my larger works. The viewer is the figure, and part of the work.

Charcoal is also made up of the most basic element: carbon. It’s very poetic, because its present in every living thing. It’s very organic.

I still do painting, but not as often. Somehow, I don’t feel that contact with it anymore. Maybe I fell in love with charcoal, and as I worked with it, I began to discover how charcoal could be manipulated.

Tate, 1999

How do you balance the physical constraints of a flat surface with the illusory elements depth and perspective in your work? In The Courtyard area, the drawings are both imagined and real at the same time. What were your considerations in exploring and balancing this duality?

The actual architectural space definitely came into consideration. I would think about how Jendela space itself curved, and what sort of element would fit best. At the same time, I wanted to create the illusion that one could crawl into these spaces if one wanted to. I also looked at the entire space as a composition on paper as well. I wanted to include elements that would ground the entire space, and that would get viewers to consider the different heights and levels.

That was all in the plan, but when I worked onsite, I had to make onsite decisions as well. There were some parts of the wall that were just too high for me to reach and draw. As such, I would then have to go and recompose that section. I’m very thankful for the technical support that the Esplanade provided throughout the process. Scaffolding was built for me so that I could reach and draw on higher parts of the wall.

⁹ Powers of Ten™, Charles and Ray Eames

1977

When I think of a city, I often think of the human presence and our interactions as pulsing through the built environment. When you were conceptualising this work, was people flow and the creating of vantage points important considerations for you?

Yes, definitely. For the entrance space of the exhibition, I included these window drawings as a precursor of things to come. Instead of drawing within a rectangle, I drew a trapezoid that would lead the viewer’s eye towards the next space. I definitely planned this exhibition with suggestions in mind as to how audiences could navigate the space, but I don’t think the viewing experience is restricted. The viewer can walk into The Courtyard, but come back to the entrance if they so desire. Of course, the manner in which the spaces are built suggests a particular order, but viewers are free to move between them.

A friend of mine said that this exhibition reminded him of a work by Charles and Ray Eames titled Powers of Ten™. It’s such a huge compliment, and it is a video that begins with a picnic scene. It zooms out towards a view of the universe, before zooming all the way back into a cellular level. My friend saw the drawings in The Courtyard as zoomed in versions of the CHAR-CITY sculpture.

I wanted to talk about a dance performance that you did previously as well. Drawing Parallel was done in 2014, and you conceptualised it as a metaphor for drawing. Why use dance as a metaphor for drawing?

Essentially, that work was about movement. Drawing is actually an incredibly physical process that is about making marks, and I see dance as a movement in space

With dance, it’s ephemeral so there aren’t any obvious marks that are being made. A lot of people have said that my works are rather ephemeral because charcoal drawings can be easily rubbed away. But if the drawing remains undisturbed, there could be a sense of permanence surrounding the work as well. On the other hand, dance can’t be captured. You could freeze it in time, but then all movement would be stilled. I see dance as equivalent to drawing because they’re both about movement.

This work was done in conjunction with Singapore Art Week, with four acts. The work begins with choreographed movements, but we later begin tearing up newspapers and magazines. This comes from me having to line the floors of my studio with newspaper before drawing. I see this tearing as an expression for the act of erasing. As much as drawing is about making marks, it is also about erasure.

This was one of my favourite works, because of its scale and the fact that I was very involved in the entire artistic process. I installed the work, but performed in it as well. We used the body as a way in which paper could be torn, dragged, and swept across; and it pushed my understanding of drawing into a different sphere.

¹⁰ Drawing Parallel, Tang Ling Nah

2014, Aliwal Arts Centre

2014, Aliwal Arts Centre

You’ve practiced as an artist for awhile now, and I was wondering if there is something you’re trying to probe at or explore. Is there something you’re trying to distill or searching for in all of your works?

Through my art, I hope to share a different view of the city with my audiences and to encourage them to enjoy parts of it that they might have overlooked. We can actually slow down, and I want viewers to know that in doing so, they can begin see the city in a different light.

The city aside, I also want viewers to realise how impermanent things are. We should be aware of our surroundings, and treasure the moments we experience. With An Other Space《另•外•空間》, the light changes in the space from day to night. This transition can’t be captured or frozen, but the important thing is to experience it and to contemplate.

An Other Space《另•外•空間》 is currently on show at the

Esplanade Jendela (Visual Arts Space).

The exhibition will run until 6 January 2019.

For more information, visit the Esplanades’s website.

Esplanade Jendela (Visual Arts Space).

The exhibition will run until 6 January 2019.

For more information, visit the Esplanades’s website.