Tini Aliman is a sound designer, field recordist and foley artist who works at the intersection of theatre and film, sound design, live sound art performance, installation and collaborative projects. Her research interests include but are not limited to, forest networks, aural architecture, plant consciousness and the variables of data translations via biodata sonification. In 2018, she was nominated for the Best Sound Design category for Life! Theatre Awards for her work for Angkat, by Teater Ekamatra. She has been involved in projects and exhibitions across Asia Pacific and Europe. Her recent projects have been presented at NTU CCA, Biennale Urbana at Caserma Pepe, Venice and Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei.

When living in the city, how often do we think about who or what we share our spaces with? The urban environment that we pass through is home to a myriad of both living and non-living critters. In its own unique way, nature has endured time and continues to endures us. An ongoing three-part project of Tini’s, Pokoknya, dives deep into these interspecies relationships. The first part of the project was presented at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art earlier this year, and the second part is part of an exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore, An Exercise in Glitch Season.

When living in the city, how often do we think about who or what we share our spaces with? The urban environment that we pass through is home to a myriad of both living and non-living critters. In its own unique way, nature has endured time and continues to endures us. An ongoing three-part project of Tini’s, Pokoknya, dives deep into these interspecies relationships. The first part of the project was presented at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art earlier this year, and the second part is part of an exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore, An Exercise in Glitch Season.

Tell us about your selection of artworks and objects, particularly with regard to how you put them together. What were some of the things you had in mind during this process?

I’m an auditory learner, so I don’t form attachments with tangible objects. For me, picking out items for this interview required a new kind of attention and distraction. Instead, I carved out an acoustic order based on the discordant rhythms of the perceived objects. I chose these objects by listening.

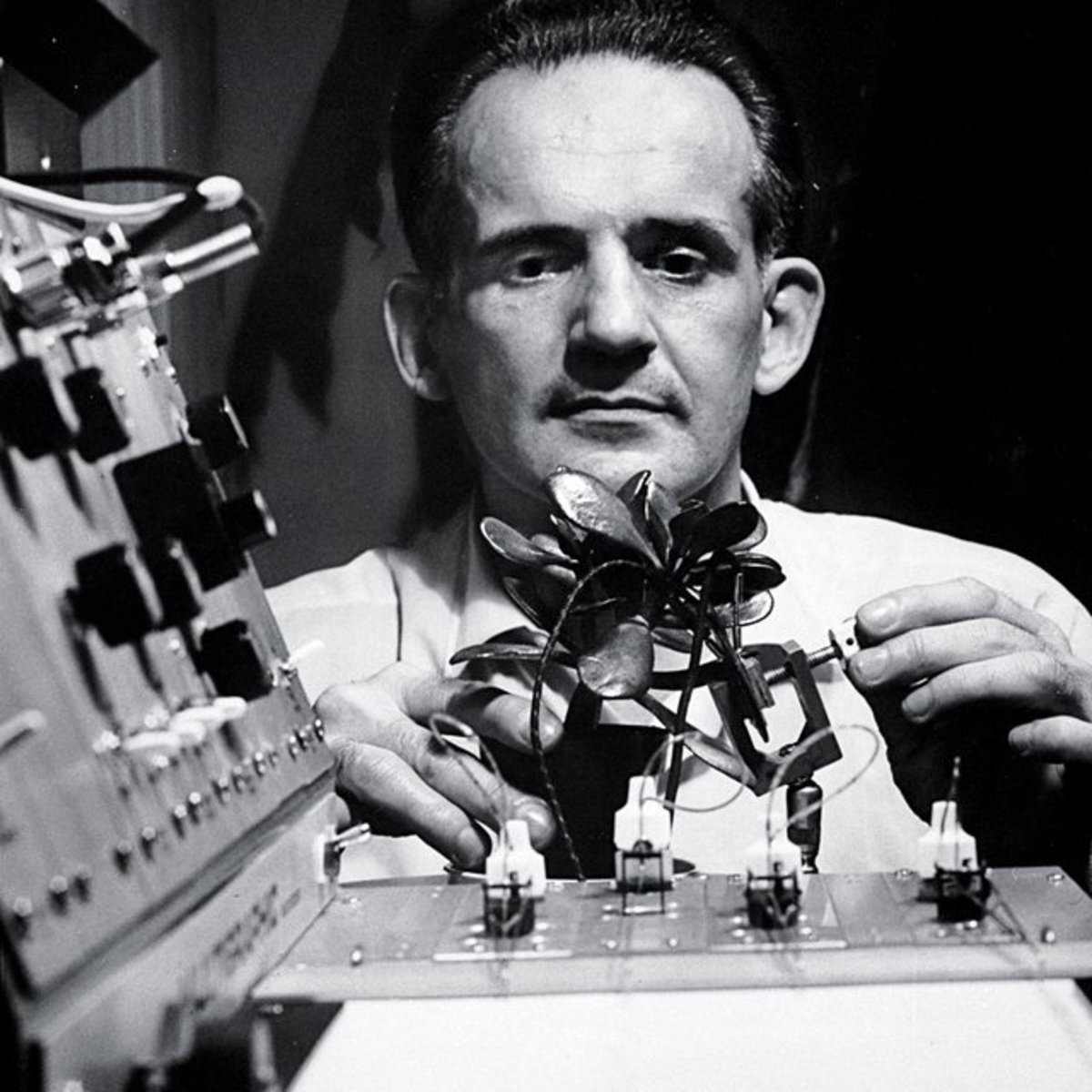

¹ Cleve Backster conducting an experiment

The hypothesis Cleve Backster had with his plant polygraph experiments was the notion that plants were emotive beings. Although Backster’s experiments have since been debunked, offshoots of the experiment and its ideas can be found in art, new age philosophy, and pop culture. Some of your recent projects have been centered around plants, and you have conducted your own experiments into examining plant consciousness as well. Could you tell us about what sparked off this research interest for you, and why plants?

Plants are good teachers, and they are actually so much fun. By being grounded, plants cannot simply walk away from a difficult situation. Instead, they developed a set of defence mechanisms, such as growth retardation, as an adaptive response to the environment and its weather conditions. At the same time, plants have very rich underground and aboveground ecosystems, which act like huge data centres, storing information and transferring them from one plant to another. They provide for their young, suck off nutrients from other plants, have memories, can see colours (according to Julius von Sachs’ red and blue light experiment), can produce signals when damaged or wounded (according to David Rhodes and Gordon Orians’ caterpillar attack experiment), move towards lower frequency sound underwater (according to Monica Gagliano’s work in plant bioacoustics).

I could go on about plants, but why I chose Baxter’s plant polygraph is because it was one of my first departure points when it comes to capturing data from plants. That has since led me towards other readings around scientific experiments on plant neurobiology — so this wasn’t really in the context of new age philosophy. It also wasn’t whether plants had emotions and all kinds of anthropomorphic qualities. The question was how as a sound technician, could I use technology to measure the galvanic conductance in plants, a form of bioelectricity, and transform that data into sound? While some artists record wind and tides, water and whales, metal, bridges and monuments, I record water movements in the leaves, in the stems, and even in the soil. This has a lot to do with my appreciation for silence, and the silenced. Through this practice, I learn more about microphone techniques and keeping the plants in my front yard alive.

While some artists record wind and tides, water and whales, metal, bridges and monuments, I record water movements in the leaves, in the stems, and even in the soil.

² Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation, Tini Aliman

2020, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

³ Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation, Tini Aliman

2020, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

2020, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

³ Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation, Tini Aliman

2020, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

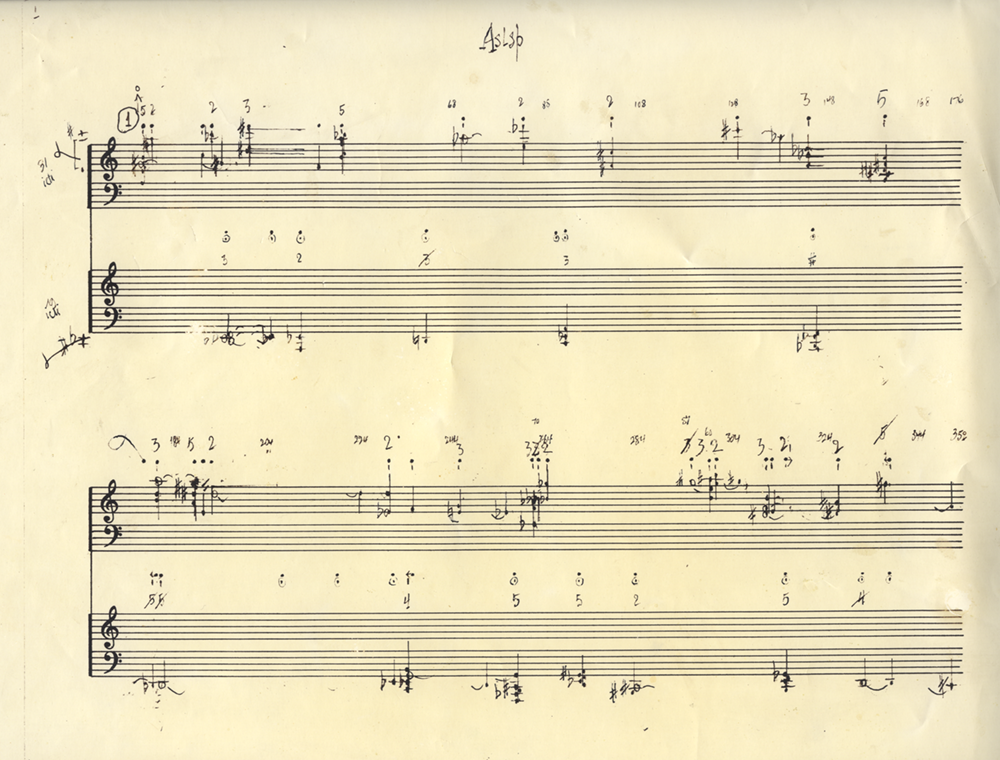

⁴ Organ²/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible), John Cage

1987

The only instructions for the piece’s tempo is in the title of John Cage’s composition Organ²/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible). The sheet music itself doesn’t have the usual tempo markings. Cage’s piece beckons the performer to take their time with it, and in doing so, asks pertinent questions about how we approach, value or understand time. Tell us about why you gravitated towards the physical score of Cage’s piece for this interview as compared to, for example, the recent performance of the piece in September where the key was changed for the first time since 2013.

John Cage’s Organ²/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible) was written in the 1980s as an open format piece. The work was commissioned by a school, and it was originally written for the piano. This ensured that no two performances of Organ²/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible) would sound the same. Two years later, the piece was adapted for the organ. Subsequently, it was performed by various performers over the years.

In September 2001, a project was launched, and its goal was to perform the piece for 639 years. As of this year, the piece has since gone through fourteen different note changes. If I live up to a hundred years old, I will have witnessed the piece being performed a total of sixty five times, with long pauses in between that last for years. I find that absolutely wonderful.

I chose the score because it acts as a symbol of contemplation and deep soundlessness, which I value a lot in my sound practice. We are constantly murmuring, muttering, scheming, wondering to ourselves, comforting ourselves — in a perverse fashion — with our own silent voices. I really like the concept of ma (a living pause) in Noh theatre. I appreciate the idea of negative space between the memory of a sound heard, and the anticipation of the next sound. During his time at a Zen Buddhist monastery, Leonard Cohen took on the name of Jikan, which means the silence in between two thoughts.

I find considering the contextual questions that frame a piece of music and seeing it as a form of ‘completed work’ as much of a meaningful experience as simply enjoying the music as it is. To quote the French essayist and poet, Paul Valéry, “A work is never completed, but merely abandoned.” This got me thinking about the open-ended and speculative nature of research, art-making, and musical composition. I’ve also been thinking about how the role of the artist has transformed over time, the role of the creator of objects, and how all of this contributes to the perceived value of a work. I just don’t think we should stop learning and branching out.

I appreciate the idea of negative space between the memory of a sound heard, and the anticipation of the next sound.

⁵ Continuum, The Observatory

2015

The Singaporean band The Observatory released an album in 2015 titled Continuum which drew heavily from Indonesian gamelan music, and featured instruments such as the reyong. Within this context, you picked out the reyong for our conversation. Why were you drawn to discussing the reyong as an instrument by way of the local band, and were there particular elements surrounding The Observatory’s take on gamelan music that resonated with you?

When discussing experimental music, I don't know how one could not cite the long-running and uncompromising Singapore experimental rock band, The Observatory. I have always been drawn to the works of artists and musicians whose ways of working are concerned with reframing, redefining or disrupting traditional ideas and expectations about music. This extends to the representations of identity, history, sonic semblances from specific places and their cultural landscapes.

The Observatory has always looked towards and worked with Asian and Southeast Asian musical elements in their practice. This includes Indonesian gamelan music, Indian Carnatic music, and experimentative collaborations, such as their recent collaboration with Japanoise avant-garde artist, Keiji Haino. To make Continuum, The Observatory spent approximately three months in Bali. They also recorded parts of the album there. The band customised a set of reyong pots to the scale of E, F, F♯, A♯, C, and D♯, which might seem as if they translated the instrument into Western musical notation. However out of respect for tradition and in embracing the spirit of gamelan, the notes are microtonal, and the songs were devised around this unique scale. The Observatory also realised that different Balinese or Javanese gamelan traditions had their own beat frequencies. The band would then intentionally tune their instruments a little differently to pay homage to these characteristics, which depend on the gamelan maker’s aesthetics and influence. Gamelan music practice is typically aural or memorised, with little or no notation used. I spent some time playing in a gamelan ensemble, and although there are numbers or symbols that can be used, the musicians mostly play from memory.

The Observatory’s adaptation, in terms of borrowing from a culture and creating something new, makes me think about the trajectory of my own practice and what I’d like to continue pursuing. I’d like to explore music and sound through synaesthetic approaches, because I’m skeptical about whether a truly pure artistic experience, one that is free of predetermining influences, is possible, especially within the context of sound.

⁶ Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation, Tini Aliman

2020, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

2020, Installation View at the National Gallery Singapore

Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation gathers together a real constellation of ideas, from gamelan music to environmental landscapes and social memory. As we discussed earlier, this work also is an extension of an ongoing research interest of yours. Tell us about how the work came to be, how you approached thinking about and making this particular variation.

Pokoknya means “tree belonging to”, or “the root of the matter”, in Malay. I’ve categorised the work, Pokoknya, into three subjects and environments.

By adapting the concept of architectural histories, I identify the first performance of Pokoknya as being real, or as something that reaches out. Seven plants were brought into a gallery, and they performed alongside collaborators from a small gamelan ensemble, electronic sound artists, and a movement artist. In response to the sounds produced electronically by the plants, the gamelan ensemble performed a song called Puspawarna. Written in the Solo courts, the piece is about nine flowers, and each flower corresponds to one of the Prince’s wives or concubines. This song is also a part of the Golden Record, which has been sent into space with the Voyager as a gift to extraterrestrial beings. The movement artist represented a banyan tree and was paired up with the ficus macrocarpa at the center of the performance. This referenced the story of alun-alun kidul from Yogyakarta.

The second iteration, Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation, is currently showing at the National Gallery Singapore. It is said to be abstract or relatively closed, and was conceived in response to the theme of the exhibition, An Exercise of Meaning in Glitch Season. This work explores the conversation around memory fragments. The videos emulate the afterlife of a performance by retracing sonic semblances and the nature of glitches. More importantly, I was thinking about how such paradigm shifts have impacted or cancelled our state of being in these strange times. During this period of time, we also rely heavily on pixels as sources of information. The work is composed of two giant speakers, which have two waveforms in playback. One speaker acts as a noise source, and the other is inverted, or out-of-phase by 180 degrees, and acts as anti-noise. The two speakers are effectively cancelling each other out.

The final piece, Pokoknya: (Working Title), is scheduled for some time in January 2021. It brings the tripartite work to a close, and I think of it as being natural or breaking open. All of these works deal with the limits and possibilities of interspecies communication.

⁷ One Year To Live, Shirley Soh

2018, Installation View at Both Sides, Now

Another work you picked out for our conversation was Shirley Soh’s One Year To Live, first presented at Both Sides, Now in 2018. The work carves out a small room within the public space of the void deck, inviting audiences to meditate on what they’d do if they only had a year to live. Tell us about your encounter with this work and why you enjoyed it. Were these observations something you had at the back of your mind in setting up how Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation would sit assuredly within the National Gallery Singapore exhibition space itself or extend an invitation to the viewer to slow down?

I remember Both Sides, Now as being one of the best local exhibitions I visited that year. Shirley Soh’s One Year To Live makes me think about attachments and intentions in my work. Why am I doing this work? Who am I doing it for? I began to acknowledge material impermanence, and it brought me to a place where I began to ask questions about myths relating to the fetishisation of artistic genius. This is the archetypal, but romanticised or idealised, image of the impoverished, mad, and wild artistic genius. We each have our own assumptions about art, and these assumptions are rooted in our individual perceptions of beauty, taste and genius.

This made me sway towards the concept of Minimalism, which has been understood as an art form that draws from philosophies connected to Asian spirituality such as Zen Buddhism, meditation, notions of nothingness, emptiness and the cosmological void. This thought plays a part in the aesthetics of Pokoknya: Organic Cancellation. The videos depict destruction, decomposition, disease, death, and dying. The act of viewing the work may be accompanied and framed by certain assumptions and blindspots, and this depends on external, environmental and personal reasons. It will also be affected by a broad range of possibilities when it comes to other predetermining influences. Ultimately, what we see or hear is largely based on what we think we know. To reiterate what I mentioned previously about plants being good teachers, choosing it as the subject of my work teaches me that the cycle continues, even towards our perceived idea of the end. Sometimes, we forget that it is okay to just let go, and play.

To reiterate what I mentioned previously about plants being good teachers, choosing it as the subject of my work teaches me that the cycle continues, even towards our perceived idea of the end.

⁸ Ingang van den Kraton te Djokjakarta (Waringin trees on the alun-alun in front of the entrance of the sultan's kraton)

Tropenmuseum, c. 1857—1874

With the work, audiences can only hear the audio clearly when they step into the artwork’s immediate vicinity to step on the pedal positioned between the tree sculptures. These tree sculptures are set up in a manner that recalls the twin banyan trees at the Yogyakarta kraton alun-alun kidul and amongst other traditions, that of masangin. Why was it important for you that the work facilitate that sort of close listening in reference to that particular geo-cultural landscape and its associated mythologies?

Alun-alun kidul was one of the first few lessons I encountered in thinking about the relationships humans share with trees. I was drawn to the story, the historical events, how humans perceive relationships with sentient beings, and how we humanise these beings according to our values and belief systems. Historically, alun-alun kidul functioned as the entrance leading to the Yogyakarta kraton. It was a ceremonial space for important officials, and a waiting area for commoners. On a darker note, this was also the same place where corporal punishments and executions were done. On a lighter note, celebrations and activities were also held there. There are many variations of the story, but what I was told when I visited was that should one walk successfully between the two banyan trees blindfolded, they would find the love of their life.

Through these lessons in interpersonal relationships and in considering the significance given to the pair of banyan trees, I saw the importance of balance in the system — good and bad, light and dark, companionship, and harmony. I bring all of this into the performative regard of the work Pokoknya. In the first performance of Pokoknya at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore, there is a moving partner in the performance artist for the banyan tree. In this iteration of Pokoknya at the National Gallery Singapore, we have a pair of pixelated trees with speakers. I felt that interaction — human or otherwise — with the sculptures was important. This would activate the cancellation.

⁹ Performance: Pokoknya, Tini Aliman

2020, Performance at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore

¹⁰ Performance: Pokoknya, Tini Aliman

2020, Performance at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore

2020, Performance at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore

¹⁰ Performance: Pokoknya, Tini Aliman

2020, Performance at NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore

There is an undercurrent that seems to underlie our relationship with nature and sound that this piece references, and it is that we are simultaneously surrounded by yet ignorant of such elements. In examining the interspecies relationship we have with nature, how has sound and the manipulation of sound provided fertile grounds for idea germination within your practice?

I am interested in presenting accidental improvisational sonic textures and punctuations, and in the capacity of post processed sound sculptures to lift these improvisations above and beyond the ordinary.

The role of the listener, to me, is an important one, because they have the potential to limit or expand the meaning of the sound. I do think that the contextual details that frame any artwork, especially the experience of it, affect the depth of understanding one would potentially have. Art is perhaps associated with more cerebral connotations and poetic expressions that draws from the artist’s personal style and sense of aesthetics. Many works of art, visual or musical, draw from multiple reference points and mediums. Art can be poetic, intellectual, traditional and artisanal at the same time.

By using natural media made in response to site-specific audio-visual topographies and environments, I hope it is clear that I have no intention to assign a voice to plants, to speak for them, to interpret or translate their stories, or to replace this intelligible vocabulary with something that our human minds can comprehend. This work is an invitation for the audience to just simply listen, and to listen deeply.

An Exercise of Meaning in a Glitch Season is now open. The exhibition is part of the Proposals for Novel Ways of Being initiative, and will run at the National Gallery of Singapore until 21 February 2021.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.