Dr. Yanyun Chen (b. 1986, Singapore) is a visual artist. She runs a charcoal-based drawing practice, and her works respond to writing — fictional and philosophical — as well as aesthetic traditions and techniques. She was presented with the People’s Choice Award for the President’s Young Talents 2018 exhibition at Singapore Art Museum and is the winner of the 2019 ArtOutreach IMPART Visual Artist Award. She received her PhD with Summa Cum Laude from the European Graduate School. She is a full-time lecturer in the Arts & Humanities division of Yale-NUS College in Singapore, the founder of illustration and animation studio Piplatchka, and the managing partner of publishing house Delere Press. She lives and works in Singapore.

The past year has been a busy one for Yanyun. Just within the past month alone, she worked collaboratively with two musicians to produce Variations and Variables for the NUS Arts Festival, and opened a solo exhibition at Grey Projects titled Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry. We managed to sit down with the artist and chat about the trajectories she has explored through her practice thus far. For our conversation, Yanyun picked out the works of Giorgio Morandi, Helene Schjerfbeck and Miyamoto Musashi; Satoshi Kon’s animated movies; and the critically acclaimed manga series, Monster.

The past year has been a busy one for Yanyun. Just within the past month alone, she worked collaboratively with two musicians to produce Variations and Variables for the NUS Arts Festival, and opened a solo exhibition at Grey Projects titled Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry. We managed to sit down with the artist and chat about the trajectories she has explored through her practice thus far. For our conversation, Yanyun picked out the works of Giorgio Morandi, Helene Schjerfbeck and Miyamoto Musashi; Satoshi Kon’s animated movies; and the critically acclaimed manga series, Monster.

2006

Let’s start with your selection of Satoshi Kon’s works and the critically acclaimed manga, Monster. Both Satoshi Kon and Naoki Urasawa delicately manipulated the drawn surface towards suspense and thrill, bending our understanding of time and space. Personally, what drew you towards these works, and what do you enjoy about them?

I’m a big fan of animation, reading manga and watching anime. I grew up spending a lot of time doing that, and I did my undergraduate degree in animation. When you watch animation and read manga, you come across a lot of interesting stories. In particular, I really like Kon and Urasawa’s way of telling stories. Both of them do a deep dive into the human nature in all of its darkness and complexities, and the psychosis of a person. They both always create very interesting characters, and tell these in-depth stories about the good, the bad and the ugly. Kon’s works occupy this space in between the light and the dark, and he also reveal details at a very slow pace. As a reader or a viewer, you slowly discover more layers to a plot or to a character as the story unfolds. When I see these works, they echo the parts of humanity that I’ve experienced before. In comparison, Monster is a post-World War II story about a doctor who is coming to terms with his own morality and the ethics involved in being a doctor. The manga has a bend on philosophy and an interest in sociology, psychology and communities.

I feel like these works subvert what we imagine comics and animations to be. We might think of cartoons as being written for kids, or being exaggerated or wacky. Instead, these are very serious texts and works.

As you mentioned earlier, you studied and trained as an animator. Do you find your training in animation foregrounding your artistic practice as it stands today, and if so, in what sense?

It wasn’t my plan to become a contemporary artist, because I was quite happy being an animator and a game designer. When you train in writing narratives as an animator, the frame is set. The audience is going to watch this rectangle, and one has to create an entire storyline based on this idea — that the frame does not move. In games, however, this is slightly different. You have to design different levels of difficulty, which means that there is a prolonged experience of interaction. The game has to get more difficult as it goes on, but it can’t get too difficult or the player will give up. Yet if it’s too easy, the player could get bored too. It was all about finding that sweet spot.

When I think about narratives in this fashion, it spilled into the way I think about installations. I hadn’t thought about doing installations until pretty recently, and to be honest, The scars that write us at the President’s Young Talents showcase was my first attempt at this. Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry here at Grey Projects is my second. Previously, I just made works to be hung. It was a very classic or traditional way of thinking about a picture. I remember inviting Alfredo Jaar, who happened to be in town, to my first ever solo exhibition. It wasn’t anything grand — I was just exhibiting a couple of my works at the NUSS Kent Ridge Guild House in an exhibition titled Chasing Flowers. It wasn’t even a gallery space. He liked the works, but then asked me what I thought about the space. That had never occured to me before. I was just damn grateful that someone was interested enough to put my works up in a public space. I realised that these sort of spatial and contextual considerations have roots in how contemporary art education is conducted. Given that my background was in illustration and animation, the size of the paper or the resolution of the digital screen was all I thought about. Yet when it comes to gallery spaces, and even exhibitions held outside of the white cube space, it becomes really important to think about what it means for this work to exist in this particular time or context. What Alfredo said was both sharp and confronting, and I really appreciated it. I really had to take the time out to think of what that could mean for me.

When I started work on the President’s Young Talents showcase, I began to think about what it would mean for a member of the audience to walk through that space. We were all given an enormous space at SAM at 8Q, and I don’t normally work with such large spaces. Initially, I didn’t know what to do with it. So I began to think about the narrative experience: how will it unfold, what will viewers see when they first come into this space, and how do you lead them through the space? When all these questions came to the fore, it started to feel as if I was telling a story. I used techniques in narratives to resolve these questions, but didn’t realise that this wasn’t something that most artists did. It was all I knew, so it took many conversations with different friends from varying background before I realised this. Many said that it was pretty difficult to describe how they felt in the space, but finally it was the poet Lawrence Ypil who likened the experience of seeing my works to that of watching a movie.

I used to make miniatures for stop motion films, and I worked in Ludwigsburg, Germany for a time making miniatures for the movie, The Gruffalo’s Child. When you think of backdrops, you don’t think of it as being part of the narrative, but it is. It has to aid the narrative. It cannot distract from the story, and it sets the tone for what is happening in the scene. I approached this space at Grey Projects with that in mind. I’m trying to create an atmosphere, and the references had to be very obvious. I made use of a lot of red lanterns in this installations, and they end up washing the entire space with this reddish glow. I see this redness as both beautiful and uncanny. What do we think of when we see this sort of red lighting? In Chinese culture, this sort of lighting gives you memories of things you’ve seen before such as temples, altars, weddings, and brothels. These references help build the atmosphere of the space, and create a narrative story. I included a prologue in the front of the exhibition that describes my relationship to my grandmother, and this was to tap onto the audience’s own memories of encountering these sort of settings. It sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition.

Jason Wee very sweetly described this exhibition as being an autonarrative, and I think that’s the right term for what I’m trying to do at the moment.

The autonarrative is autobiographical — I do draw on my own family histories, but it is also fictional. I won’t tell the audiences what is real and what is not.

In this space, I’ll tell the story as I want to. The point of the story no longer resides within its veracity, but is in the fact that everyone has scars and that everyone has a family member. These things are universal, so audiences can project their own experiences onto the spaces I create. I think there’s a lot of value in that, and I quite enjoy thinking about it in this way.

² Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry, Yanyun Chen

2019, Installation View at Grey Projects

2019, Installation View at Grey Projects

You tap on rather personal stories both in Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry and The scars that write us. Many of these stories touch of topics that are raw, complex, and deeply rooted in societal expectations or norms. Personally, what do you find interesting, rewarding or productive about going through these issues with art?

Parallel to this, I was doing my PhD and trying to understand what the notion of nudity is. It was more philosophical, but I based my discussion around case studies in Singapore. In the context of our country, how do people respond to the idea of being naked? What sort of laws do we have? Who has been persecuted? What kind of art has been censored? I didn’t do a practice thesis, so I did a research thesis on the topic instead.

At the end of the process, my claim was that nudity functions as a kind of fiction. It’s a simple claim, but I think it is very important. It means that everybody has the agency to write their own fiction, and no one has more right over another to determine what one body should mean.

That became my own argument, and I realised I needed to reclaim my own nudity. I ended up asking myself the same question I posed in my dissertation — what does this nude body of mine mean, and how do I put it in a space, like Singapore, where it could be seen as a taboo topic both legally and socially. How do I embed it into a space without having audiences question why the body has to be naked?

How do you talk about body without relying solely on mere depictions of the body?

Exactly. My works have nudes, but no one questions it because it makes sense. When you think of wounds and scars, the naked body almost seems like a natural, logical step to take. The associations are parallel and it makes sense. Nobody has come up to me to ask about why the body has to be nude. When they see the topic at hand, it becomes clear that of course — the body has to be nude. It no longer becomes a question that has to be asked. I’m intrigued by that. What sort of strategies can an artist use to deal with figures and the figurative such that it doesn’t trigger the defences of a more conservative member of the public? The nude, as a figure in art, has developed over time. It’s constantly evolving.

With this, and a couple of other factors, I ended up tapping on personal family stories in my work. I was actually very nervous when I was doing up The scars that write us because I wasn’t sure how my family would take to the idea. Even though the body depicted is my own and not theirs, the stories still touch on our collective vulnerabilities. It’s very raw. I had many long conversations with them, and I had to figure out which aspects of these stories to place on the walls of the museum.

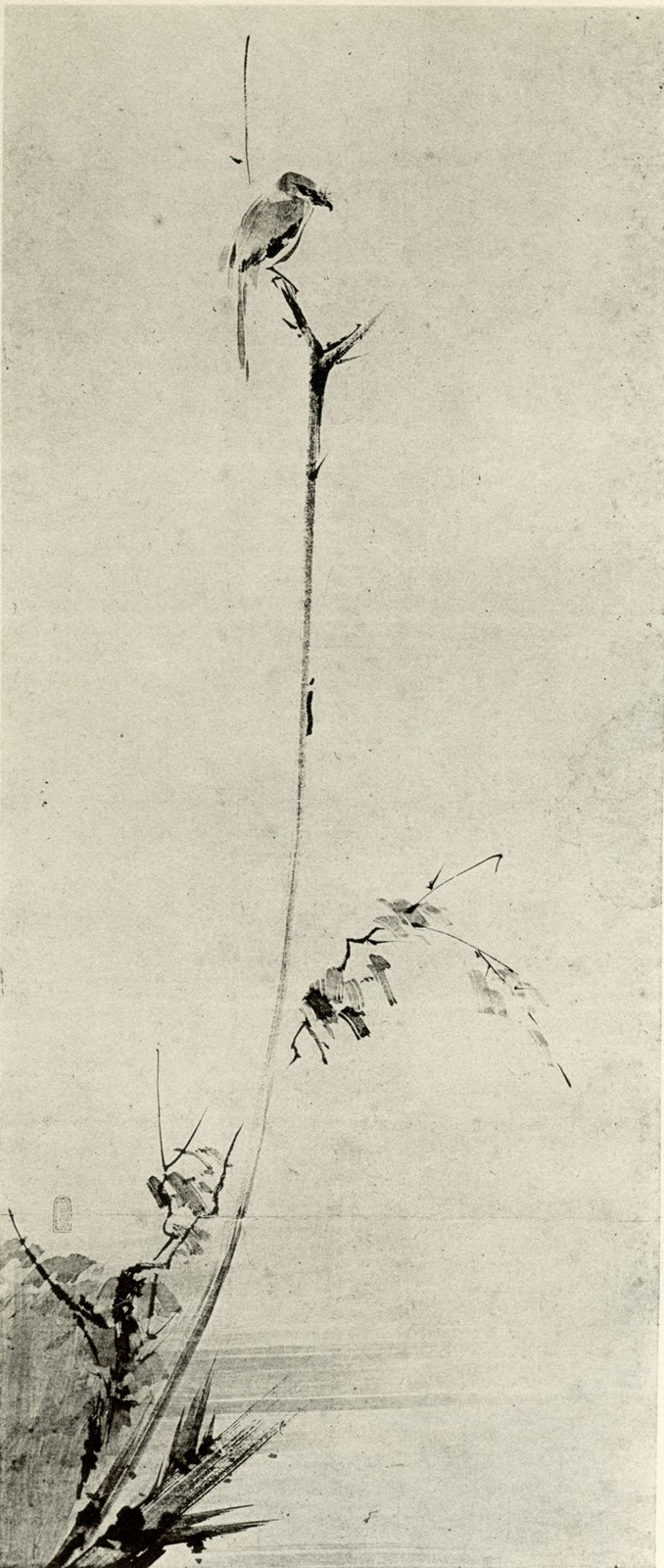

³ Shrike on a Dead Tree, Miyamoto Musashi

Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts

With the past few exhibitions you’ve put on, you’ve experimented quite a bit with displaying text alongside your visual images. This ties in quite nicely to another artist you’ve selected for our conversation, Miyamoto Musashi. Musashi was a skilled warrior, who paintings were always understood in relation to his writing. How do you personally work through the relationship between word and image when working through your various projects?

This comes from a long working relationship with Jeremy Fernando. He’s a writer, and I’m the artist. For the longest time, I didn’t have the words to describe what I was doing and I wasn’t able to think deeply enough in terms of language. When I started doing my postgraduate studies, I encountered a lot of readings in philosophies and the works of many writers that I thoroughly enjoy. Words began to seep into my works because there were things that I wanted to say that I couldn’t do with the visual.

With The scars that write us, for example, I couldn’t describe a reflective thought through the image. The scar was the image. The thoughts and the feelings behind that experience had to come out through text. I didn’t do it as a form of healing, but now that I think about it, the healing is in the language. Someone asked me if I felt differently about my scars having put on this exhibition, but no I don’t feel differently about them at all. They are still there, and they will still evolve. They are keloids, so they’ll change but they will not disappear. What I wanted to do was to see if we could change the way with which we look at scars by providing a different way through which we can know or read a scar.

Now with Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry, I was struggling with questions about where to place my voice. I knew the aesthetic of the show. I wanted something that was reminiscent of 1930s or 1940s Shanghai, but I knew that if I had just left it at that level, it would seem as if I was just recreating a wedding scene. How could I show that I disagreed with these issues? Artists have manipulated objects in order to show the contemporary confronting the antique. However, some of these objects are real antiques that I actually use, so I didn’t want to alter them in any way. Changing them also didn’t feel like the right gesture. The show discusses my relationship with my grandmother, and I didn’t want it to come across seeming like we do not have a relationship or that there was no reconciliation between us. This show is my nod towards the fact that she probably went through a similar process of deconstruction. When you humanise someone you completely disagree with, in this case my grandmother, that is the act of reconciliation itself. I was trying to find a place for myself within this exhibition, and I didn’t want audiences to leave the gallery feeling this sense of tension. I wanted to leave them with sorrow and to evoke in them memories of their own grandparents. I ended up putting my voice in the text. Some of the people who’ve visited the exhibition do not come from Singapore or Chinese backgrounds, yet they too have said to me that they understand the concept of dowry objects. It is surprisingly similar, and there is something universal about this work.

It has also been interesting for me to note who responds to the work. For example, do the men respond to the work? Given the fact that the men don’t deal with the dowry at all, what would their interaction with the work be like? Someone asked me where the groom is in all of this, and why I chose to leave the groom out of the conversation. When you’re thinking about the dowry, the groom actually doesn’t come into the picture at all. He’s the patriarchal figure around whom all the drama unfolds, and he already commands the space. In the context of a Chinese marriage, it is the women who figure out the economics of this relationship.

Grey Projects is located in Tiong Bahru, which was known to be a neighbourhood where rich men kept their mistresses. In light of the area’s history, I thought it was particularly apt that this show was exhibited here.

That is very interesting because I didn’t know about that at all. I lived here over a decade ago, and I remember that our neighbours were a group of KTV hostesses. Every evening, you’d see them dressed up and on their way to work. I didn’t know about the history of the place, but I always had that visual in the back of my mind — of beautiful women, all gowned up and ready for the night. That stayed with me, and that was my reference point.

When I saw Grey Projects and I thought about how narrow the space was, it reminded me of Hong Kong. Things were a little rickety and the wires were all exposed. Given that, I really thought this sort of story would fit well into the space.

The experience of the exhibition starts even before the viewer steps into the space proper as well. As it is located on the second floor, there is that sense of trepidation when you work your way up the steps to the gallery — much like the sort of anticipation that fills everyone on the day of a wedding.

I wanted the experience to start downstairs, so I made sure to hang a red lantern at the bottom of the stairwell as well. I joked with the people at Grey Projects and told them that it would look like a brothel at night. If dodgy men came up the steps with expectations, it would have meant we succeeded in creating that atmosphere.

⁴ Flower Flights II, Yanyun Chen

2018

⁵ On Human Bondage, Yanyun Chen

2018

2018

⁵ On Human Bondage, Yanyun Chen

2018

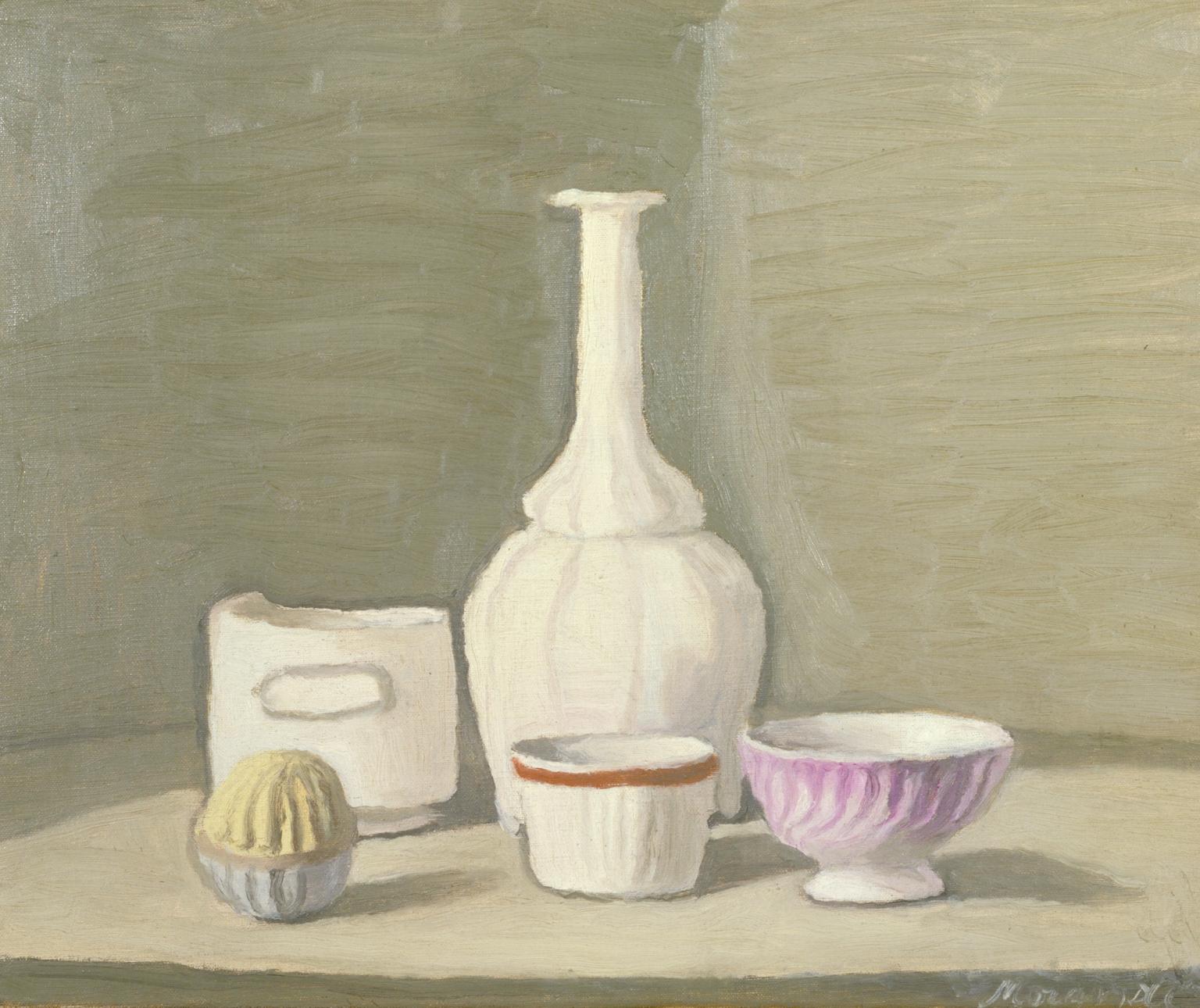

Tate, 1946

Finnish National Gallery, 1905

Quite a few of the works you’ve chosen here, such as Giorgio Morandi’s and Helene Schjerfbeck’s work, strike me as capturing the light of a particular time of day or moment in time. It seems apt to bring this up as we’re now talking about lighting and the atmosphere light evokes.

I see colours and light, even though I don’t work in colours. I think lighting creates a mood and captures a particular time of day. I enjoy the works of Giorgio Morandi because he creates the most uncomfortable compositions out of very mundane objects. He places them so close together with only a sliver of negative space between them. He also works with natural light, which earned him a reputation for being a master at capturing Italian light. Many of his works are portrayals of the same objects, just at different times of day. There’s something about artists who manage to work with these small gestures, yet manage to bring a whole new dimension to the work that I really love.

Helene Schjerfbeck is another such artist. She was a Finnish artist who had health issues most of her life. As such, she just stayed at home and ended up painting whoever came by her house. When she first started out, her works betrayed her classical artistic training. Yet as time went on, there was a real degradation in the way she thought about portraiture, shapes and light. There are such subtleties and combinations that are specific to these painters. I love that idea. One doesn’t have to do a lot. You just have to do one thing, but to create new textures or to create truly succinct ways of getting a message across.

Both Morandi and Schjerfbeck were best known for their works in the still life genre. I understand you have created works that could be described as being a part of that tradition as well. When one thinks of a contemporary art practice, the genre of still life doesn’t often come to mind. How do you approach working on still lifes, and why were you drawn to creating those works to begin with?

When I came back to Singapore in 2014 after studying in Sweden, I was broke. I had no money, and it was impossible for me to hire live models. I love working with bodies and I love working with people. As such I had to find something else to practice with. I wanted something that was organic and that would shift, yet remain still enough. As such, I started working with flowers.

I had all of these misconceptions about drawing and painting flowers when I first started out. I realised that flowers turn towards the sun, and that they wilt. Not only do they wilt, they all wilt at different rates. I had been used to working on a single drawing for five weeks, but now I had five days or less to work on something. After I finished one drawing, I wanted to challenge myself by doing more. It was sort of a game as well, where the difficulty would just keep rising. The more I drew flowers, the faster I got with drawing them and with coping with how they changed.

Sometime later, technicality was no longer an obstruction. It dawned on me that this was a rather morbid process. I was just standing here, watching these plants die, non-stop. It was interesting to be in a space where I was witnessing something pass away right in front of me, albeit at a very slow pace. When I became conscious of it, it opened up a plethora of questions for me — what does it mean to be a caregiver? What does it mean to watch something die?

I got to a point where I wasn’t sure what I could glean out of this process anymore. I took a pause, and began to look for what’s next. My works are never repetitive, and I’ve always wanted my works to move incrementally either away from something or towards something else. I stopped doing these flower drawings for awhile until a collector brought up the challenge of conserving works on paper in Singapore’s humid environment. Because of this, I ended up experimenting with different materials. What would charcoal look like on wood? How do I prepare wood? How would charcoal look like on fabric? Flowers were a subject matter I was familiar with, so it was very easy to use them in my experiments. They became my ceteris paribus whilst I figured out what sort of surfaces I could draw on with charcoal.

I don’t have an overarching topic that I’m obsessed about. I tend to enjoy the little challenges that push me along. The thing that I do maintain is the fact that I work with charcoal. There are all of these projects that I play around with, so it’s always about finding the next challenge as compared to staying within a single space.

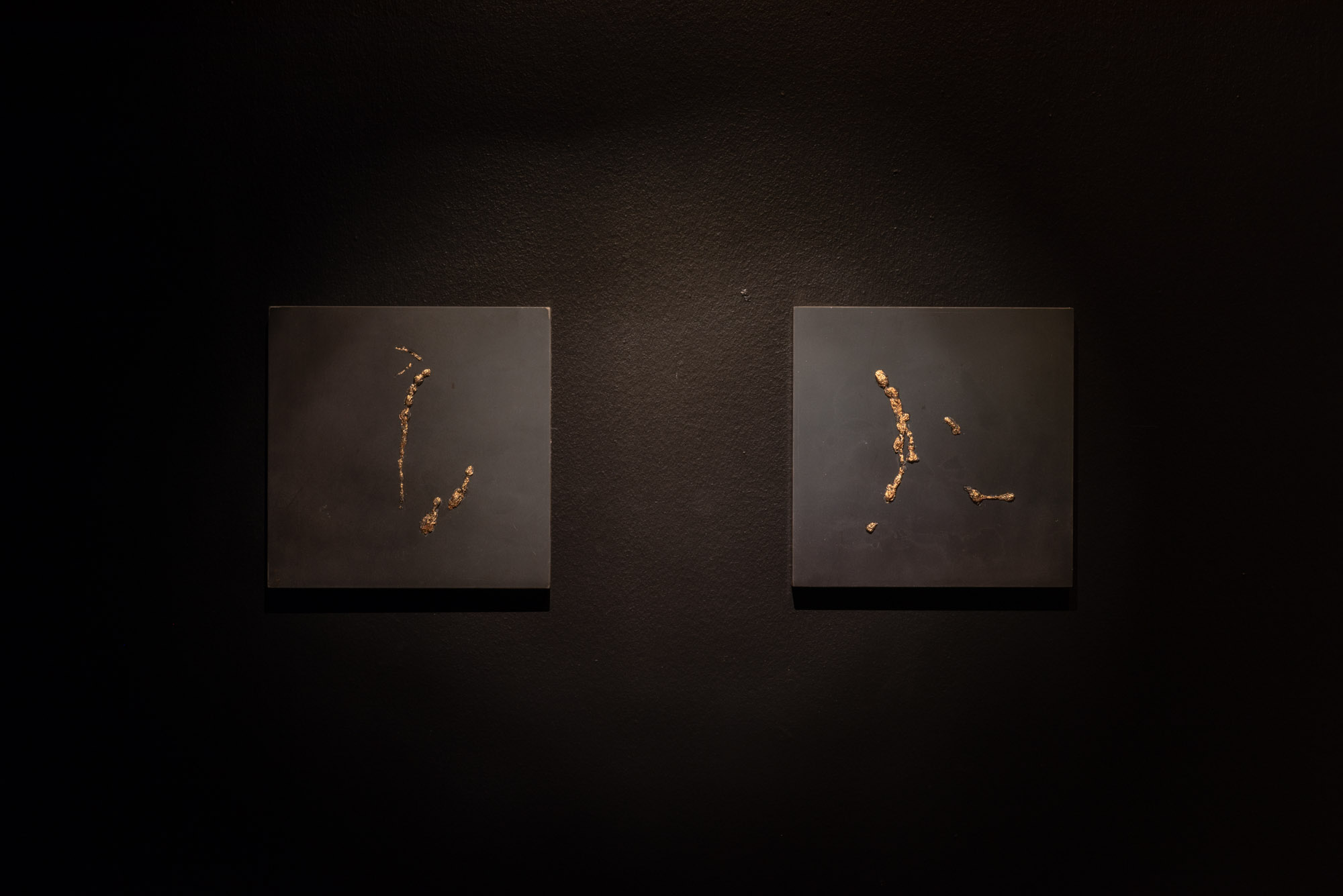

⁸ The scars that write us, Yanyun Chen

2018, Installation View at 8Q @ Singapore Art Museum

2018, Installation View at 8Q @ Singapore Art Museum

Charcoal is a very basic tool with which many artists start out with. It is associated with sketching, and many then abandon charcoal in pursuit of other mediums such as oil, film or photography. What continues to intrigue you about charcoal as a medium?

The school that I went to aligns itself with an Italian-French tradition, and its curriculum comes from the 18th century. It is very old school that teaches its students in increments. First, students learn to mimic. After mimicking, students learn to give language to that object. Then students learn to paint in sepia, with temperature, with a limited palette before finally working with a full palette. We were introduced to charcoal as a way in which we could train our precision in copying. I fell in love with it. I love drawing a lot, and I enjoy how dense or how dark a piece of charcoal can be.

I remember doing a cast of the Unknown Woman of the Seine. The story of this woman is that her body was found in the River Seine, and that nobody claimed her when she was found. Nobody knew who she was, but she died with such a serene and beautiful expression that a death mask was made of her face. I thought of her story and how she drowned, and the sort of lighting that was created. She looked as if she was rising and falling all at the same time. Once that sensation hit, it all came together in that moment.

Charcoal can create a lighting so specific that it can look as if the surface is vibrating. I’ve just been trying to capture that experience ever since, and I try to do it with all of my works and installations.

How do I make works that are almost visible but not quite, such that the viewer has to spend some time looking at it?

It’s interesting that you think of the medium as a means of conveying that sort of movement. Coming back to the idea of still life as a genre that captures a particular moment in time, the idea of maintaining a sense of buoyant movement in the work seems to almost sit at odds with this.

When it comes to philosophies and ideologies, when you hold onto a thought too strongly, you end up strangling it. Take any idea and push it to the extreme, and you’ll soon find that it no longer functions the way you want it to.

Georges Didi-Huberman once asked how we could arrest a thought. Do we hold it in our hands, or do we arrest it in our fists? How do you connect and touch a thought without strangling it to death? How do you keep it alive, and how do you let it breathe? When I heard his lecture, I was immediately reminded of a lesson I learnt in Sweden. When we draw an object, we tend to draw its contours or its outlines. Yet, one of our lecturers pointed out that this wasn’t always necessary. You don’t always have to fill in an object completely to depict it accurately. What happens when you get rid of some parts of the drawing where the foreground cannot be visually differentiated from the background? The moment that happens, we discover the lost and found line. When you follow the contour of a drawing, sometimes the line is there. That is when it’s found. Other times, it is lost.

That rhythm of the lost and found line allows the viewer to fill in blanks. It makes the drawing come alive because it gives the viewer the space to imagine what’s going on. It makes the drawing intriguing.

The lost and found line allows for energy and breathing space in a drawing.

Thought is similar. If you give a thought breathing space, it will come alive. The moment you try to grab onto it really tightly, it will die under its own strain. For me, I try to capture atmospheres and moods whilst allowing for breathing space so that things can be kept in balance. It is simultaneously about the need to arrest a thought, and a need to let that thought pulse.

It has been a whirlwind past six months for you, and I understand that you’ve constantly sought to push yourself incrementally through your practice. Having these developments and awards play out, and with an upcoming trip to New York lined up, are there particular things in mind that you’re looking forward to exploring?

I’m still trying to digest what on earth just happened. It was a lot. I’ve had a lot of fun discovering and experimenting with making installation works, but it’s also become a space for creating autofiction for me. Autofictions often seem very intimate, and installations, on the other hand, seem very big and grand. I think I’ll stay within this contrast of scale a little bit.

I’m hoping that I get a break this time around, and I’m looking forward to heading up to New York. I’ve never been to New York before, and I just want to go see how artists there do things. How do they create sensations? A lot of how I think about art making and its strategies now comes from my time in Sweden. I’ve also been intrigued by science fiction and have been reading Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea. I’m looking forward to being in a different place, absorbing new things, and seeing what sort of stories rise to the surface as a result of the things I encounter.

Stories of A Woman and Her Dowry is now open.

The exhibition will run at Grey Projects until 27 April 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

The exhibition will run at Grey Projects until 27 April 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.