Slow

Conversations

Issue: On Listening

Filed under: found objects, installations, music, sculpture, sound

Issue: On Listening

Filed under: found objects, installations, music, sculpture, sound

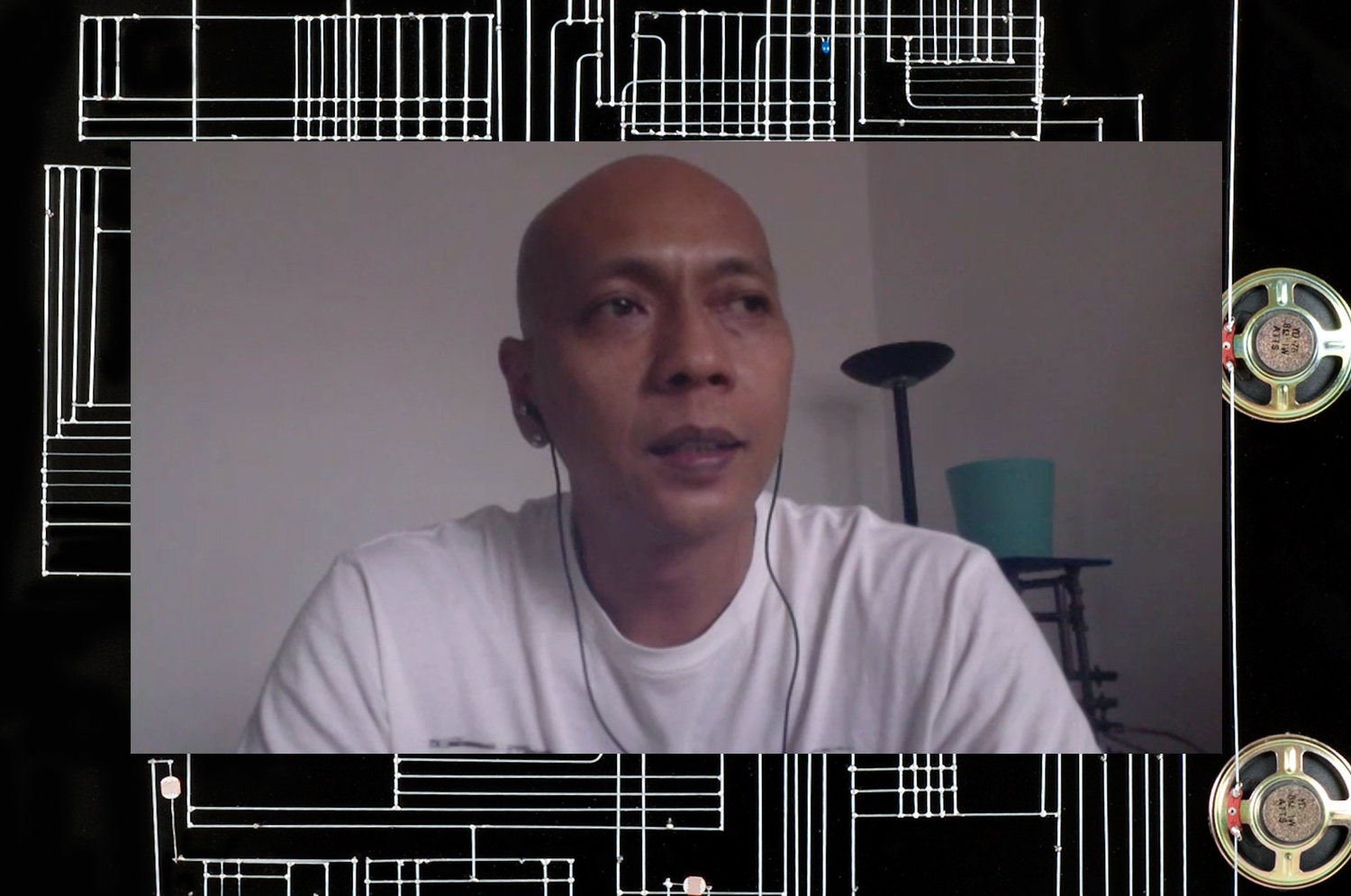

Zulkifle Mahmod (b. 1975) is one of Singapore’s leading sound artists. ZUL has been at the forefront of a generation of sound-media artists in Singapore’s contemporary art development – one of the genres of international contemporary art-making that has been garnering interest for its inter-disciplinary approach and experimental edge. ZUL represented Singapore with a sound art performance at the Ogaki Biennale in 2006, and was Singapore’s first sound artist with a full-on sound sculpture at the Singapore Pavilion of the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007.

When discussing sound art in Singapore, the practice and work of sound artist Zulkilfle Mahmod immediately comes up in conversation. ZUL has been at the forefront of these development, and his practice has pioneered the use of sonic elements within the fine arts. With a focus on the sculptural qualities of the everyday objects that surround us, ZUL’s works often incorporate copper pipes and electromagnets. In doing so, the artist hopes that his works encourage close listening and a renewed understanding of our urban environments.

When discussing sound art in Singapore, the practice and work of sound artist Zulkilfle Mahmod immediately comes up in conversation. ZUL has been at the forefront of these development, and his practice has pioneered the use of sonic elements within the fine arts. With a focus on the sculptural qualities of the everyday objects that surround us, ZUL’s works often incorporate copper pipes and electromagnets. In doing so, the artist hopes that his works encourage close listening and a renewed understanding of our urban environments.

In our email correspondence prior to this interview, you spoke about the fact that your practice largely

draws upon or finds inspiration from the streets. Tell

us about the importance of the everyday within your practice and how you draw inspiration from these day to day interactions.

The streets are very important to me. I like going on long walks, and there are times where I walk around the city aimlessly just to get a feel or a vibe of what’s happening. I travel by public transport and I enjoy hanging out in coffeeshops as well. That’s where people communicate freely over coffee, lunch or dinner. I don’t mean to eavesdrop, being in spaces like the coffeeshops helps you to understand what’s happening in Singapore at the moment and what people are thinking about. Someone might have had a good day or they might have had a bad day. These are all things we can relate to, and this is how the streets influence my work.Sometimes on these walks, I bring my recording device with me. It’s a binaural recording device, which means that the microphone component is in earpiece. So to a passerby, it might just look like I’m listening to music when I’m actually recording soundscapes. For me, the content of what’s being recorded or said is not as important as the sound itself. I see conversations, for example, as just another soundscape.

You were trained in sculpture and have produced drawings or works on paper throughout the course of your practice, on top of your work as a sound artist. Tell us about your journey with sound or sound-based art. What does working in sound mean to you, and what drew you towards working with sound or sonic elements?

I trained as a sculptor, and so I’ve always been fascinated by material, objects and spaces. In 2001, I met this Dutch artist who was doing a lot of dance music on his computer. This was the early 2000s, so sound art or making music on your computer was still a pretty new concept. He introduced me to this software, Logic Pro, which has since been bought over by Apple. From then on, I became fascinated with the medium of sound. I began doing a lot of recordings and reading up on the subject matter in order to see how I could take this further. It was in 2004 that I scrapped visual elements from my work to focus solely on sound or making sound works. There are so many facets to sound, such as installations or the performative. Sound is very important to me, and I’m still experimenting with it today. I’m still looking for new ways to present sound works because audiences can have quite a short attention span when it comes to sound works. Even when it comes to sound works with an interactive element, that takes time and effort on the part of the audience. If that interaction takes a little longer than unexpected, the visitor might say that the artwork is broken or the interactive element is no longer working. In order to establish a relationship with my audience that’s more meaningful, I stopped inlcuding interactive elements in my work. This way, my hope is that they take something away with them from an exhibition of my works.

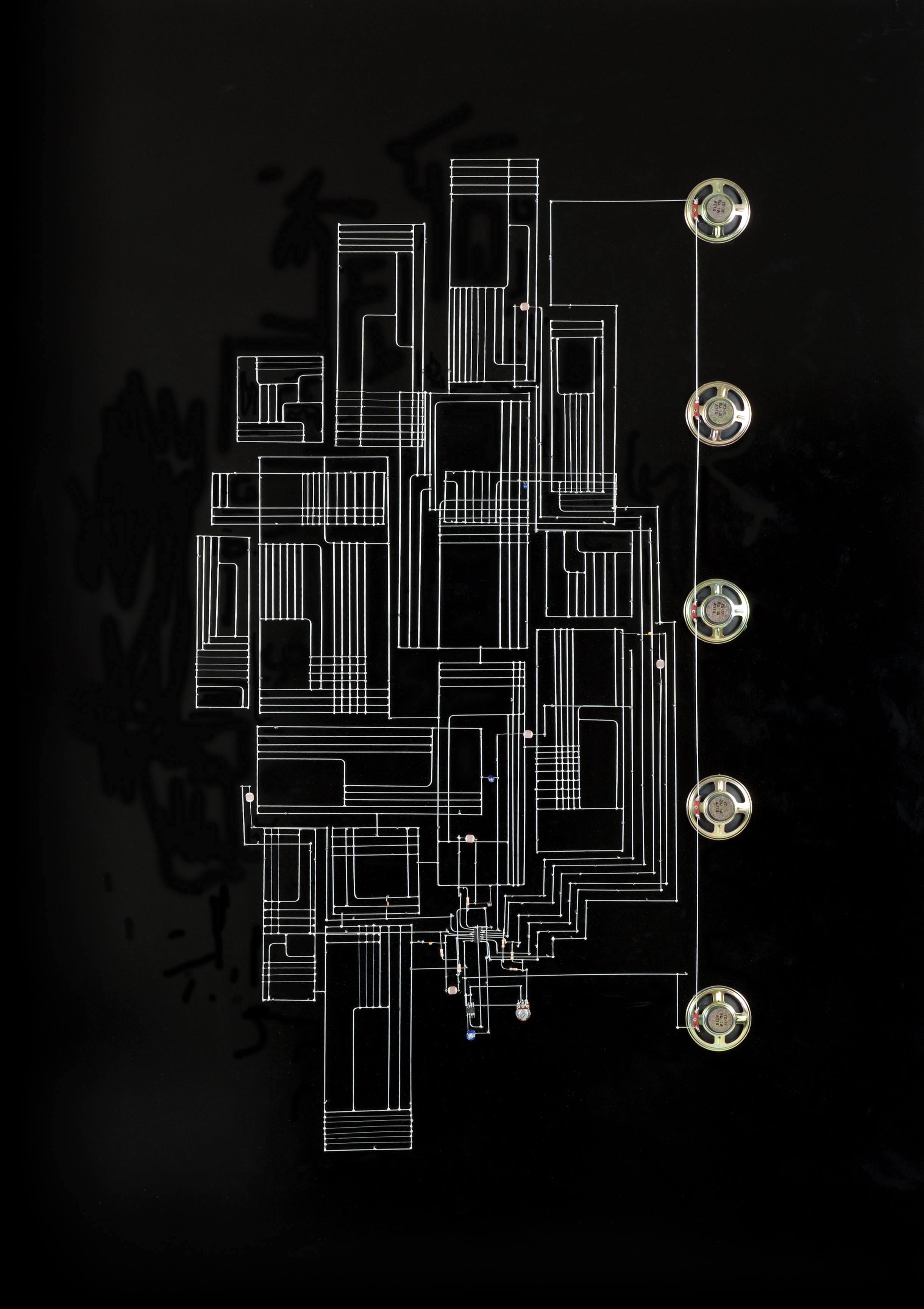

¹ Resonance in Frames, Zulkifle Mahmod

2019, Installation View at Fost Gallery

² Resonance in Frames, Zulkifle Mahmod

2019, Installation View at Fost Gallery

2019, Installation View at Fost Gallery

² Resonance in Frames, Zulkifle Mahmod

2019, Installation View at Fost Gallery

When we approach an encounter with art, there can be this tendency to rely heavily on the visual — almost as if our eyes need something to latch onto when we step into an exhibition space. Have you been interested in unpicking this dynamic an audience might have with a gallery space and the conventions around negotiating or navigating that?

When I first started working with sound, I’d present works that had little to no visual elements. I’d place them within dimly lit or dark spaces so that the audiences would just step in to focus on the sound. I later realised that even space itself can be thought of as a visual element, and this was something I learnt from a curator I met.I don’t blame the audience. We do have a need for the visual. If there’s absolutely nothing in a room, then it’d just be complete darkness, and that can be quite disorienting. Ultimately, it depends on what I want to explore with my work. There are times where I don’t give in to my audiences. I don’t want the audiences to feel pampered or to sink into a comfortable pattern. Tension can sometimes be useful, so it really differs from project to project.

The idea of listening, for me, is important. There is an abundance of sound that comes with living in a city, but some of us just block it out. But quite interestingly, people pay attention to them when you put them in museum or gallery contexts. These everyday sounds are quite beautiful to me. They have their own rhythms and melodies.

The idea of listening, for me, is important. There is an abundance of sound that comes with living in a city, but some of us just block it out. But quite interestingly, people pay attention to them when you put them in museum or gallery contexts.

³ 51 prepared dc-motors, 241 m rope, cardboard sticks 25 cm, Zimoun

2019

2019

One of the artists that you’ve found incredibly interesting is the composer and artist Zimoun. In his kinetic sound sculptures and installations, industrial objects respond to one another to produce what has been described as “tonal and visual complexity”. Movement is pivotal to this process, and this is something that can be observed within your works as well. Could you tell us about how you see the place of movement — both seen and unseen — in the context of your own practice?

Movement is quite important for me. I began using the sounds of physical objects interacting with one another, as compared to sounds that are composed or tuned, about five or six years ago. These physical objects include everyday items such as copper pipes. When you place a series of moving objects within an artwork, the work is being composed in real time. Not all the sounds are played at once, and I began noticing that certain visitors would begin watching the solenoids, or the electromagnetic devices, to ascertain which item would move or be hit next. Our minds tend to wander that way when we’re looking at something, and that unseen movement is interesting to me. That's the emotional side of things, and that's what I'm trying to portray or showcase within my works. When you listen to a sound, or when you encounter this installation, how does it make you feel?

⁴ Dialog, Zulkifle Mahmod

2016, Installation View at Esplanade Tunnel

⁵ Dialog, Zulkifle Mahmod

2016, Installation View at Esplanade Tunnel

2016, Installation View at Esplanade Tunnel

⁵ Dialog, Zulkifle Mahmod

2016, Installation View at Esplanade Tunnel

We’ve seen you use industrial or everyday objects in your own works as well, and in particular, you've circled back to using specific objects. For example, objects such as copper pipes and solenoids have been featured across works such as Resonance in Frames and Dialog. How do these tools or items figure within your working processes, and why have you come back to them over and over again in making work?

I've been using everyday objects in my work ever since I started making art. I was using found objects or readymade objects even in my sculptural works. The copper pipes, for instance, kept coming to me whilst I was making all of these sound works. I think that this material is very important to me. We are surrounded by pipes such as these everyday. I find it interesting that you say that these materials recur across several works of mine. If someone makes multiple ceramic artworks in succession, we wouldn't think of clay as a recurring material. For me, these objects are materials that I use within my works. At the end of the day, my works always revolve around ideas or concepts such as the everyday. I like the fact that copper pipes, for example, can function as a reference to connectivity. This goes beyond the literal connections between people, but even connections to historical or social memories. Having said that, I haven't used copper pipes in my works for awhile. I'm moving towards experimenting with other materials.

Are there specific qualities that you look out for in the objects and materials that you incorporate into your work?

When it comes to the exact objects or material I use for my works, I'm not very particular. The most important thing to me is the idea or the concept that I want to explore with a particular work. I start from there, then move towards looking for the appropriate materials.The most important thing to me is the idea or the concept that I want to explore with a particular work. I start from there, then move towards looking for the appropriate materials.

For our conversation, you’ve also picked out a song by Iwan Fals. Iwan Fals is known for his lyrical compositions that often contain searing yet relevant socio-political critique or commentary. Could you tell us a little more about the influence Iwan Fals has on the way you think about music or music-making, and what you enjoy about the song Surat Buat Wakil Rakyat?

What I like about Iwan Fals, and his music, is his honesty. He has his ear to the ground as to what's happening in Indonesia, and his music reflects the voice of the people. Surat Buat Wakil Rakyat is composed as a letter to a minister. The song asks that the minister not sleep during parliamentary sessions. Most people can relate to this sentiment, because we sometimes see our parliamentary ministers sleeping during these sessions. These moments get caught on television, and this song remind them of their duty as representatives of the people. Iwan Fals is able to translate these everyday situations into his music in such an honest way.Yeah. And sometimes it is quite tongue in cheek or solo, sadly works out quite, I guess cheeky, like, I think a lot of people find find it humorous as well. And that makes it like, yeah, very relatable.

Humour is key because not everyone listens to a serious message. I'd say that Jack Neo's movies operate in a similar way. His movies are classified as comedy, but when you watch them you'll find that they touch on certain social issues or concerns.⁶ #014 (from Sonically Exposed series), Zulkifle Mahmod

2013

⁷ #020 (from Sonically Exposed series), Zulkifle Mahmod

2013

2013

⁷ #020 (from Sonically Exposed series), Zulkifle Mahmod

2013

On that note with regard to music and music-making, let’s talk about the Sonically Exposed series. In many ways, these sculptures function in a manner similar to musical instruments. When thinking about musical instruments, most of us have rather preconceived notions in mind of what is and is not an instrument. What sort of possibilities have emerged for you from experimenting with and creating these gadget-instruments, and what sort of boundaries do they allow you to push?

There are no boundaries when it comes to these gadgets. Even when I'm performing, I enjoy creating my own unique instruments. This might also be a result of my training as a sculptor. With the Sonically Exposed series, it was about presenting simple electronics in different formats. With the works in this series, all of the wires and electrical elements are exposed. I have another set of instruments where everything is, instead, contained within a case. There are so many possibilities for me to play around with when it comes to making my own instruments. Even if I use the exact same electronics, I can produce different sounds and no two instruments sound the same. I see it as a process of discovery. I can't stop building my own instruments — it's almost an addiction that keeps growing.

I'm fascinated by the exposed lines with the Sonically Exposed series. These works raise questions as to what lies underneath the surface or behind the walls. What are the things we don't see: pipes, cables and wires? When you expose these inner workings, we can get a better idea of how these wires are connected and work in tandem with one another. At the same time, there are also certain wires that can't come into contact with one another. In a way, I think it speaks to human relations as well. It's important that we don't get our wires cross with one another. We have to be mindful of others as well.

You mentioned making your own instruments, and how you’ve found yourself incredibly drawn to that. What do you enjoy about making your own instruments and these processes of experimentations?

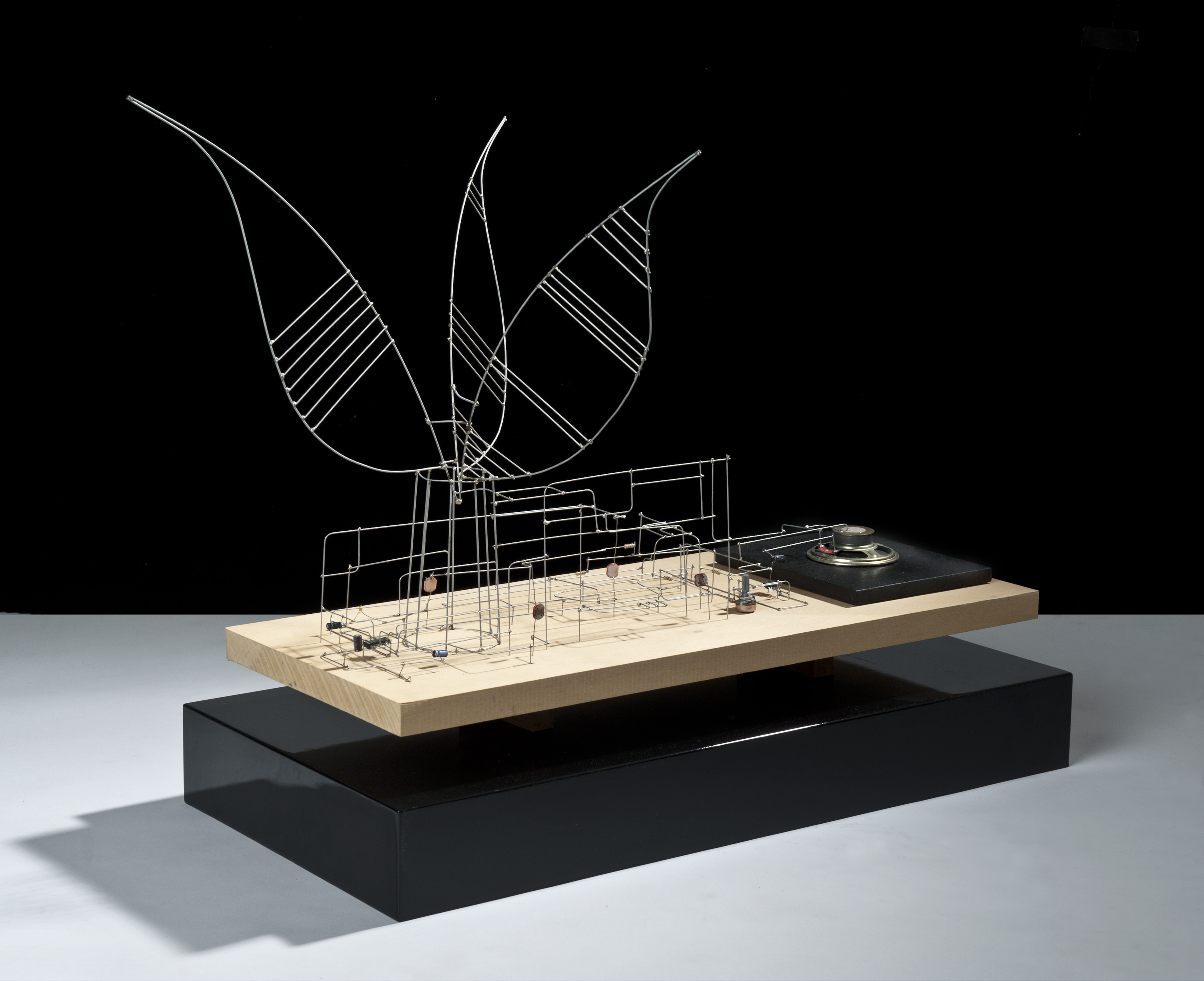

It comes back to that process of discovering things. How many different ways can the circuitry be done? How will the instrument be cased? Will the instrument be something quite sculptural? On that note, making my own instruments is quite a sculptural process. The form of the instrument is something that I can play around with, and in doing so, the work becomes something of a sound sculpture. One thing leads to another and that's the beauty of it.⁸ ZUL: Sonically Exposed

2014, Installation View at The Private Museum

⁹ ZUL: Sonically Exposed

2014, Installation View at The Private Museum

2014, Installation View at The Private Museum

⁹ ZUL: Sonically Exposed

2014, Installation View at The Private Museum

“Deep listening” is a term coined by composer and thinker Pauline Oliveros, and in many ways, this is something your practice works towards and finds resonance with. In facilitating deep listening experiences through your works, how important is it for you that the encounter is framed as a conversation or a two-way dialogue between the viewer/listener and the work?

It's very important to me because it allows you to actually find meaning in a piece you're listening to. Some of us don't actually listen to what's happening around us. Once you start listening, it's a conversation between the work, the audience and the physical space. It's a dialogue between these three things. Deep listening is very important to my work, but I don't always have control over how audiences relate to my work. Even if I've tried my best to ensure that visitors feel comfortable within a space, I can't control the exact direction or flow of this three-way conversation.

Once you start listening, it's a conversation between the work, the audience and the physical space. It's a dialogue between these three things.

Sound always relates to the space it is being played in, and the same song can sound very different when you hear it through your headphones or in an echoey cave. How does the question of space figure within your working processes, or is this something that you tackle at the stage of presenting the work?

It always depends on the space given to me. Sometimes I work with white cube spaces that don't have much character to them, and I'll try to engage the space in a dialogue, no matter how minimal. I've worked with symbolic spaces as well, including a monastery in Slovenia. That resulted in a very different kind of site-specific dialogue. Often, I only really get to explore this facet when I'm on-site and setting up. Each space has its own aural architecture, which determines how it responds to the work.The headspace of the audience member is also an important consideration. If the work is a binaural performance, or utilises headphones, which results in a three-dimensional listening experience.

Religious spaces have a deep connection to sound and sound making as well, and often are host to activities such as communal prayer, singing or chanting. Could you tell us more about how you found the experience of working with a historical and religious site such as the Dominican Monastery at Ptuj in Slovenia?

The monks circle around the space, doing their evening meditations, and the work I presented kept these rituals in mind. Coming back to the idea of deep listening, I built a sound sculpture around these meditative schedules. In order to get a sense of the work, one has to move around it. The sound was kept to a minimum, but when it responded to the acoustics of the monastery space, the sounds and vibrations created were quite beautiful. Although the monastery was decommissioned, I think the building still retains a certain sense of spirituality. It was a very peaceful experience, and I enjoyed making that work very much.¹⁰ SONIC HORIZON. Listen But Why?, Zulkifle Mahmod

2019, Installation View at Dominican Monastery at Ptuj, Slovenia

2019, Installation View at Dominican Monastery at Ptuj, Slovenia

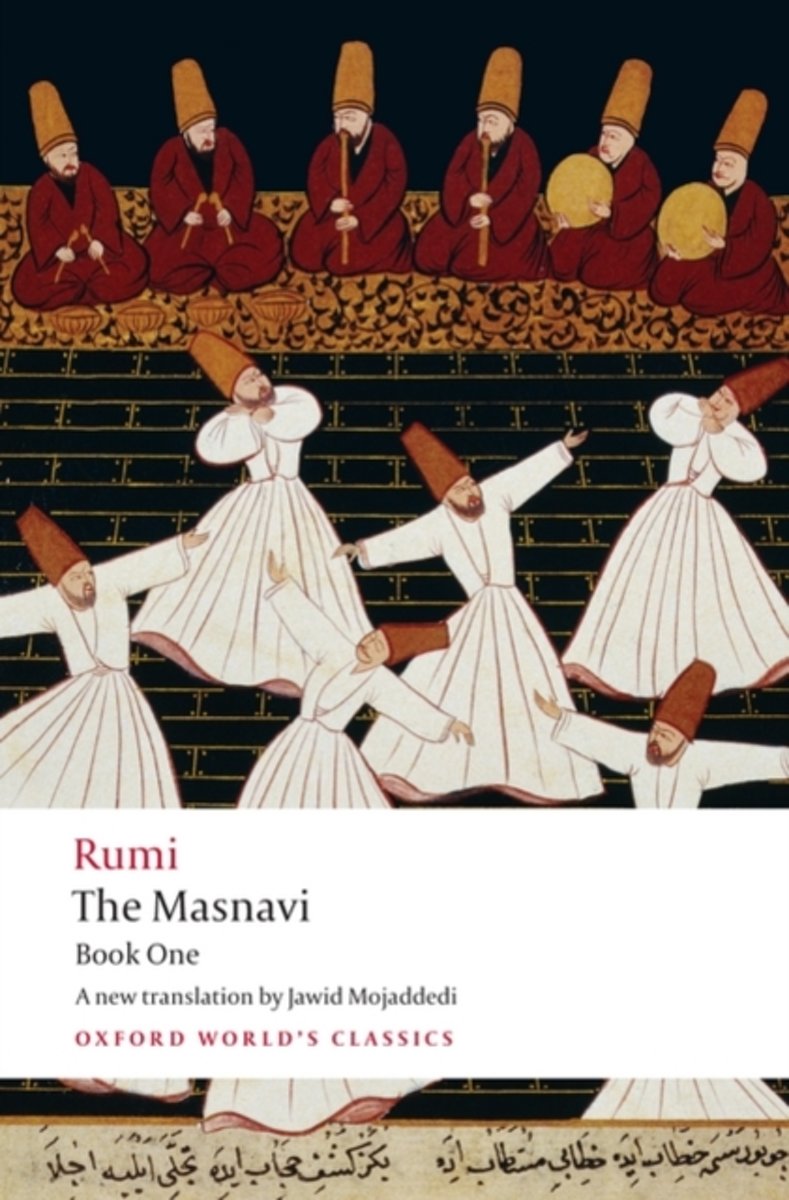

¹¹ The Masnavi (Book One), Rumi (translated by Jawid Mojaddedi)

On that note regarding the spiritual, let’s talk about your relationship to Rumi’s poetry. His poems often speak of an ongoing search for the divine, and so it was so interesting that you picked them out for our interview. Tell us about how you relate to Rumi’s poetry. Do you see parallels between the journeys in Rumi’s poems and your own relationship with sound or sound making?

I’ve always enjoyed the mysticism and spirituality of Rumi’s work. His poems are about the discovery of secrets, and his poetry has bearing on the way I approach life and how I see my work. It's hard to extricate my life from my work because it's interconnected. Most of my works have spiritual elements in them. Sometimes it's really clear, and other times it's a little more concealed.

I think Rumi's poetry has always had this effect on me. There is this poem of his that warns against falling into deep slumber. There's always beauty or a secret lying around. With patience and perserverance, they'll unveil themselves in time. Particularly with the context of this pandemic, I think that his poetry has just become more relevant. We're living through these really uncertain times, and we're all searching for certainty.